When Photographers Collide

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be but I find myself (in full grumpy old man mode) wishing that some things in the brave new world of digital photography were more like they once were. An image I recently saw of a crowd shooting autumnal dawn over Maroon Bells in the Colorado Rockies (courtesy of Dale Keller) started me thinking about how photography has almost become a competitive sport at some locations.

Maroon Bells crowd - © Dale Keller

Along a 200m stretch of shoreline 2 or 300 photographers had lined up to take essentially the same composition. Apparently fights have even broken out when one photographer gets into another’s frame. Now, I don't know about you but the prospect of hustle and bustle and a bit of argy-bargy weren’t the things that attracted me to making landscape photographs.

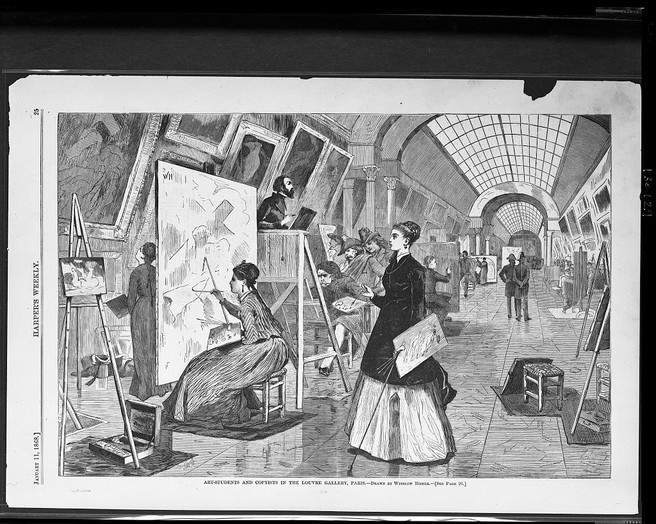

Where is the sense of achievement in making images in this way? This isn’t photography, it’s merely trophy bagging, ticking a box and moving on. This isn’t the way to learn how to make meaningful photographs. These people are not photographers they are copyists, something that’s far from new as can be seen in this engraving of the Louvre by Winslow Homer.

For the would-be painters in this scene, I can see the redeeming possibility to learn technique. I’m not sure that this is the case for the would-be photographers at Maroon Bells. Of course, there’s a natural tendency, having seen a great image, to think, “I want a bit of that!” But it seems to me that these people are trophy hunters seeking instant gratification rather than artistic insight.

On my recent trip to Iceland, I revisited many locations that I have been to over the last fourteen years. In the past, it would have been normal for my group to be the only people making images – in fact, not that long ago, at one location I remember the group being photographed by a local who presumably found it very strange that we were there to make images of his backyard. The winter months were especially quiet and, for someone from an island as crowded as the UK, the space to make photographs was always a wonderful luxury.

So why the huge increase in photographic visitors, as opposed to common or garden tourists? Perhaps, as a leader in the vanguard of photo tour companies, I’m part of the problem by encouraging this kind of tourism. I’d love to say that these people had come to learn, come to broaden their photographic horizons that the decade and more that I, Joe and others have devoted to trying to raise the bar has sparked a quiet revolution. But, sadly, this dream doesn’t seem to be supported by the evidence. Having watched other groups and listened to their chatter, the feeding frenzy more often than not seems to be driven simply by a need to imitate images that have gone viral in posts on social networks. Humans love to jump on bandwagons but it might be wise sometimes to pause for a moment and see whether it’s actually going in the right direction.

Modern technology plays another part in the tripod wars. It’s commonplace now for people to tag their images with GPS data. But what’s the rationale for telling the world and his wife where an image was made? And why the hell do we need to specify a location to the nearest few meters? I also wonder what our obsession with naming is about. A year or two before Galen Rowel’s untimely death a couple of photographer friends and I visited him in his Bay area gallery. We were flushed with excitement about our recent visit to the Pariah Canyon - Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness in Northern Arizona and regaled him with no doubt shallow tales of our experiences. This almost uninhabited landscape has a dearth of place names and to compensate for this we had invented our own, often poetic or humorous, tags for many of the locations we had photographed. This might kindly be seen as a practical navigational exercise. But Galen was sharply dismissive, regarding our naming as an attempt at appropriation rather than simple labeling. At the time I remember being slightly offended by what I regarded as his high and mighty attitude to our light hearted naming. However, with the perspective of the intervening years, I have come to realize one very important truth: a good image is a good image regardless of where it was made. Naming it doesn’t make it a finer image and, in fact, I can see at least one reason why doing so might diminish rather than enhance our interpretation.

Any information we attach to a photograph changes how we view it and the most obvious example is a caption. These basically fall into three types: factual, poetic and the irritating art-speak “Untitled # 1”. I should say that I find this irritating not because I walk away uninformed but because it is such an affected self-referential device. Just “#1” or even “ “ would be better! Most landscape photographers pick one of the first two options. Either one adds a layer of meaning by informing - or perhaps skewing might be more apt - the viewers’ interpretation. Images labelled with the names of famous places are impossible to view with an unfiltered eye, all the viewer’s cultural and personal knowledge of that place being brought to bear. Of course for some really well known places and views, we don’t even need a label to bring this mechanism into play.

One rather unedifying reason for location disclosure is competition -

Perhaps the problem is not the incontinent sharing of location information but rather laziness or a lack of creative drive on the part of the audience. It’s a given that humans are basically lazy, that we try to cut corners whenever we can. We can hardly blame David for making a good image and he’s far from the first to have his work imitated: Frederick H. Evans “A Sea of Steps, Wells Cathedral” was so often imitated that the Cathedral authorities had to stop access for photographers.

What has changed in recent years is the widespread distribution of images via the net. The almost instantaneous and free transmission of such photographs means that we no longer need to invest in an artist in order to see their work, we no longer need to buy a book or print or even a magazine. Other web tools make it a trivial matter for people to find where to place their tripod legs. The one saving grace is that, unfortunately for the wannabees, in the world of artistic endeavour taking short cuts simply leads to second-class, imitative work.

Or perhaps I have too jaundiced a view and it’s not laziness but simply a failure of confidence that leads to imitation. On a recent tour to northern Norway a client brought with him a hefty sheaf of images of the area printed off from photographer’s websites. A quick Google search had produced what he obviously felt was invaluable source material. At least once a day the sheaf would come out of the bag and he would ask, “Can we go here? I want to shoot that.” Sometimes it was hard for my co-leader and I to persuade him that “that” wouldn’t work because “that” wouldn’t even be there with a metre of snow covering the ground or because it was a windy day and there wouldn’t be any reflections or simply that it was the wrong time of year.

The question I kept asking myself was why was he trying to replicate someone else’s composition? That isn’t being a photographer, it’s not much more than being a camera operator. And I have to ask myself why anyone would pay the premium to travel with experienced photographic tutors and not take advantage of their knowledge and insight. There’s a famous saying that seems quite apt; “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and he'll eat forever.” So my aim when teaching isn’t to hand images out like sweeties – how patronising and unhelpful that would be – but rather to assist people to find their own. In fact participants learn most not from the honeypot locations but from those where they have to really work to make an image.

Photographs are necessarily always ‘of’ the world but if we want to move beyond illustration I feel that they must evoke emotional responses that are not bound to a particular place. A famous place is weighed down with unavoidable and often unwanted connotations. You may make a view of such a place that is atypical, that is perhaps even unrecognisable, but as soon as you name it the image is burdened with all that has gone before. The image may be admired for its novelty (though it may also be criticised for this!) but it can never completely escape from its predecessors. In an anonymous place, the photographer is more likely to be free of the unwanted connotations that arise from images of iconic locations. Another obvious problem with photographing any of the honey-pot locations from standard viewpoints almost one hundred and seventy years after the birth of photography is that one can guarantee that someone else has been there in a better light.

Let’s set this libellous suggestion to one side and ask why else one might photograph the great view. Might it just be to explore the photographic possibilities for yourself? Humans learn best by example, so travelling to the famous view and making an image might teach you something about how other photographers have solved the complex problems of composition in that place. This habit of learning from the efforts of past masters is an entirely honourable tradition. Many have spoken of standing on the shoulders of giants, of their achievements being possible only because of those who have gone before. The key is to use what you have learnt merely as a stepping-stone on the way to finding your own voice. The original should act as an inspiration, it should be the launchpad for a new flight of discovery. Unless we treat image making in this way it is all too easy to produce endless empty (Cornish) pastiches of other photographers’ work. A quick flick through the camera press will show how many have sadly failed to learn this lesson. By all means, photograph the famous place but try and make the images your own.

My ideal kind of location would be anonymous, the image’s exact identity hidden. Anonymous is not merely a synonym for unknown but also suggests an unassuming place. It has been my experience that my best images were made in quite ordinary places. The intent of many landscape photographers is to make an image of somewhere extraordinary; mine is to reveal the extraordinary in seemingly mundane wild places. In places such as Bryce Canyon or Yosemite it is relatively easy to make an exclamatory image. We are more quickly made aware by such loud messages. But isn’t it tiring to be shouted at all the time? It is much harder - but ultimately more satisfying - to make an image that is contemplative, lyrical, allegorical or ambiguous. In order to do this, we need to be free of preconceptions and we need to have the space to feel. Only then might we learn to look at the landscape so that we once again see wonder in the commonplace. And, more importantly, only then might we leave the herd and have a chance for our own voice to be heard.