Thomas Peck looks at the tradition of the pastoral landscape & questions whether the pastoral is a peculiarly English phenomenon…?

Thomas Peck

The real pleasure of photography is that it forces me to slow down and really look. That’s never easy in our rushed world, so a chance to stop, look and see is truly valuable.

In a previous article we looked at Alan Hinkes’s photographic depiction of the Sublime. High up in the Himalaya, in the death zone, Hinkes photographed awe-inspiring landscapes, where man was insignificant and puny in the face of massive and indifferent nature. Hinkes, whether consciously or not, was tapping into an artistic genre. In the 17th and 18th centuries artists had deliberately sought to capture the emotional impact that particularly mountain landscapes had created in the viewer. The exhilaration that comes from dread and fear: The Sublime represented ‘awesome’ nature in the original sense of that word.

Looking down from K2 at 8000ms. Base camp is 10,000 ft down. An image of man in the face of awesome nature. Hinkes relates how this climber in the image didn’t make it – hit by an avalanche whilst attempting the summit.

If Hinkes’s pictures capture a sense of the Sublime, then Harry Cory Wright’s images tap into a contrasting artistic genre – one that runs alongside the Sublime, but that works on a completely different subject and emotional level: the Pastoral. Instead of the drama of mountains and glaciers, excitement and awe, we have the tranquility of fields and streams, quietness and nostalgia.

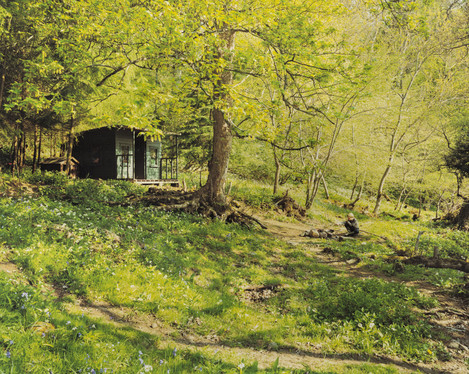

Image 1. Caption: A tranquil woodland scene. Man’s gentle interaction with the landscape – an image of the pastoral. Harry Cory Wright: Holly and Beech, Wye Valley Herefordshire

What do we see when we look at an image like Holly and Beech? And what do we feel? A woodland scene of a path rounding a mature beech tree. Spring has just begun. The viewer is invited to imagine walking through the image and follow the path. Where the path comes from, and where it goes to, are hidden in the darkness of the under glade, giving the image a slight air of mystery. But this is not a threatening mystery, it is gentle and sympathetic.The emotional tone of the image is tranquil: the dominant colours are light greens and pale yellows, complemented by soft browns. Everything is light, evanescent. It feels like an escape into an idyll

Image 2. Caption: Farmland and woodland – man and nature - in close harmony. Harry Cory Wright, Oaks. Tilhill, Surrey.

Unlike Hinkes’s images which juxtapose the insignificance of man faced with the hugeness of nature, Harry Cory Wright’s images depict a more harmonious relationship between humans and the countryside.

That tradition stretches back to antiquity. The pastoral in art often depicted a Golden Age, when man lived in harmony with nature. Hellinistic and Roman wall paintings regularly featured idealised landscapes. Such scenes were revived in the Italian Renaissance and then taken up particularly in France. Claude, Watteau, Poussin painted arcadian idylls with shepherds and peasants in imagined idealised panoramas.

Image 3. Caption : Et In Arcadia Ego, Nicola Poussin, 1637. Arcadia – symbolizing the pure, rural, idyllic life, far from the city.

Whilst there is a strong tradition of the pastoral on the continent, perhaps the most important artist to paint pastorals was British: John Constable (1776 – 1837). Constable no longer depicted idealised images of ancient Greek/Roman satyrs, nymphs or shepherds, rather he focused on contemporary images of land workers in familiar English bucolic surroundings. The scope of his landscapes was limited – he rarely travelled outside his native Suffolk, London and the south coast. But although his images are of down-to-earth folk in rural settings, they are still highly idealised. The sense of Arcadian peace infuses his images – indeed it is one of the main reasons his paintings have now become so popular (he was never financially successful during his lifetime). The Hay Wain (1821) is exactly such an image. When first exhibited at the RA it failed to find a buyer. Now it is recognised as one of the greatest and most popular English paintings. As we all know that picture so well it is perhaps more interesting to look at other works by Constable.

What makes these images so popular? The reason, I would suggest, is two-fold. Firstly, Constable painted what he saw in the countryside (literally, he was one of the first to compose directly from nature). For many this contrasts with their own experience of life which tends to be urban and city-led. Constable’s scenes evoke a nostalgia from the viewer. This is very much an element of the pastoral – a sense of something lost that was better. This yearning was as true in the 18th century as it is now. Constable was painting at the height of the Industrial Revolution, so bucolic scenes of Flatford Mill were not representative of the experience of the vast majority of the population. Secondly, the manner in which they are painted – the style itself - is naturalistic. It is easily comprehensible. Unlike Turner for example, whose paint marks become more and more abstract as he seeks to convey the inner state of mind that the weather or landscape evokes, Constable’s brushstrokes simply sought to reflect what he could see. (Constable’s heirs in artistic terms are the Impressionists who developed the impasto technique in the late 19th century).

Image 5. Caption: Fen Lane, East Bergholt, c1817. John Constable. The artist’s nostalgia – the view is of the lane Constable walked along to get to school at Dedham as a boy. The church tower is not in reality visible from this exact viewpoint.

In terms of subject matter - bucolic, technique – naturalistic and emotional impact – nostalgia, we come very close then to the imagery of Harry Cory Wright. These are inhabited landscapes. But whilst the hand of man is evident in the pathways, the fields and the canals in the photographs, the impact of man is subdued. Man and nature are in balance. When figures do appear they are placed in idyllic situations. These images are a comforting source of physical and spiritual sustenance. Harry Cory Wright’s images are an escape. They are landscapes of and for pleasure.

Image 6. Caption: The idyllic innocence of youth: Path on the big bend, River Wey, Surrey. Harry Cory Wright

As with so many artistic traditions the pastoral – in the sense of the inhabited but still idyllic landscape – is counterpointed by the opposite: Man’s detrimental encroachment on nature. This has been a rich vein for photographic exploration for many decades. One of the seminal moments in that stylistice development was an exhibition held at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House (Rochester, New York) in January 1975. "New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape" (insert a link here) The exhibition had a ripple effect on the whole medium and genre, not only in the USA, but in Europe too where generations of landscape photographers emulated and are still emulating the spirit and aesthetics of the exhibition.

Image 7. Caption: The girl playing innocently in the lake has strong overtones of arcadian purity. Midday, Top Lake. Glyndebourne, East Sussex. Harry Cory Wright

The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion. The photographers were reflecting on the increasingly suburbanised world around them, and a reaction to the tyranny of idealised landscape photography that elevated the natural and the elemental. This photography was increasingly politicised and reflected, unconsciously or otherwise, the growing unease about how the natural landscape was being eroded by industrial development and the spread of cities.

Image 8. Caption: Is this not like the Garden of Eden? Beside the River Tees. Teesdale, County Durham. Harry Cory Wright.

In this light the truly pastoral now seems like an ironic dream. Alexander Gronsky in his award winning series Pastoral 2008 – 20012 shows how our longing for an arcadian escape seems futile in the ever increasing urbanization of the landscape space.

Image 9 Caption: The sun shines and shadows are cast on a modern Arcadia. Alexander Gronsky Pastoral 2008 - 2012

Gronsky was born in Tallinn, Estonia and is now based in Latvia. His Pastoral 2008 – 2012 series was made in the outskirts of Moscow and approaches the idea of man’s impact on nature from a paradoxical point of view.

Image 10. Caption: We have a strong desire to commune with nature. But here we can’t escape the city. Alexander Gronsky Pastoral 2008 - 2012

This is ironic pastoral. Unlike the soft pastel idylls and the nostalgic yearning of Cory Wright, Gronsky shows the desire of humans for communion with nature, but contrasts it with the looming shadows of the ever-present city.

Image 11. Caption: Instead of pastel shades and sylvain glades we see litter in the woodland grove. Alexander Gronsky Pastoral 2008 - 2012

A last thought and a question for OnLandscape readers: All of the Constable and Wright images seem to me to be quintessentially ‘English’, not only in terms of subject matter (after all the Constable and Wright images in this article are images of England…), but also of style. The lanes, the pathways, the rivers and the fields – they couldn’t be in Wales or Scotland, they just look very English. And the way they are depicted – the softness, the colour, the implied nostalgia – also seem very English. Which leads me to my question – is the pastoral in some sense a very English approach to image-making?

image 12. Caption: A pastoral irony. There is no escape. The city edgelands are industrialise and littered. Alexander Gronsky Pastoral 2008 - 2012

Can we think of images, or photographers, working in Scotland or in Wales, who we might describe as ‘pastoral’? Or do the mountains, the valleys, the seascapes of Scotland and Wales lend themselves to a different artistic treatment? Closer to the sublime perhaps, or at least the picturesque. This isn’t meant as a value judgment on images made, or photographers working in the different territories, but simply as an enquiry – does the landscape define the style, or can one overlay the style onto the landscape?

Alexander Gronsky has an exhibition running from 14th April - 12th June at The Wapping Project Bankside Gallery which is well worth a visit!

References:

Harry Cory Wright’s book Journey Through The British Isles (ISBN: -13: 978-1-8589-4367-1) and website

Alexander Gronsky website