Forging and Expressing Meaningful Connections

Kas Stone

Kas Stone is a full-time photographic artist and writer based in Atlantic Canada, where her work is inspired by the wild coastal scenery and moody weather right outside her door. She can’t believe her good fortune in being able to make a (modest) living doing what she loves.

“Landscape Photography and the Meaning of Life”. It’s a bold title, to be sure. And it runs the risk of sounding wildly pretentious. Still, I chose it to catch your attention (it worked, didn’t it?) and inspire you to think more deeply about the relationship between what you photograph and who you are.

Ultimately the title pokes a stick at the pesky question that is – or should be – at the heart of all our image-making: Why?

Why do we choose to make landscape photographs rather than other types of photographs? Why do we prefer some kinds of landscapes over others? Why do certain seasons or weather conditions inspire us to take our camera out, while at other times we prefer to stay home and work at our computer? And, as we’re scrolling through the seemingly endless stream of images on that computer, why do some images make us pause, and an occasional one even stops us, spellbound, in our tracks?

Subscribers to On Landscape are an introspective bunch, so I know I am not alone in pondering these questions. Regular contributors (notably Guy Tal, Alister Benn, Rafael Rojas, David Ward and Joe Cornish) have written extensively and eloquently about the Why of what we do. Yet, each of us brings our own perspective and style to this weighty question, so I hope mine may contribute something of value to our collective search for an answer.

Shattered is characteristic of the Atlantic Coastal Barrens in autumn and gives a sense of the harsh conditions its inhabitants face.

Why landscape photographs?

Given the variety of potential subject matter in the world, why do some of us choose almost exclusively to photograph the landscape? The explanation lies, I think, in the interplay between motivation and inspiration.

Motivation can be thought of as the reason or practical purpose for our image-making – what we hope to achieve when we take our camera out into the countryside, what we plan to do with the images we bring home, and who their intended audience is.

Sometimes the source of our motivation is external. For example, we may make landscape images to win a competition, satisfy a commercial client, expand our website portfolio, or gain approval from our photographic peers. While these may seem important goals in the context of our daily social and economic lives, the resulting images are unlikely to be especially meaningful to us because their creation is shaped by other people’s preferences rather than our own.

When, instead, we allow our personal thoughts and feelings about the landscape to guide our image-making, our motivation becomes internal.

Internal motivation often has more to do with the experience of making the photographs than with the photographs themselves. People who become landscape photographers commonly pick up a camera for the first time to record, remember and share these experiences. Perhaps a wilderness adventure or a journey to some exotic location, or, for those with scientific interests, their interactions with the landscape’s flora, fauna or geology. Over time, as we become proficient enough with the technical tools of our craft that we can start looking beyond them, this initial, outward-looking approach to image-making often evolves into one that is more introspective and artistic.

Increasingly in these stressful times, however, our internal motivation for heading out into nature with a camera is for therapeutic purpose; to escape, to cogitate, to restore our sense of perspective.

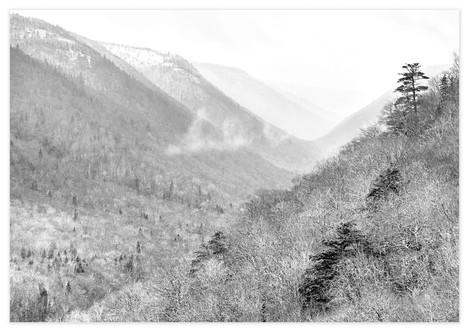

First Snow came at the end of a nasty, wet, October day when the temperature fell just enough to turn the rain into big flakes of snow – and my gloomy mood into a gleeful one.

The Bog’s Last Fling as the autumn colour fades to winter monochrome, a time of wistfulness for some people, and delight for others.

Landscape photographers are usually – although not universally – introverts, at odds with the unrelenting connectivity and busyness of modern society. The wild outdoors is our refuge. Even without a camera, our ramblings in the countryside help to revive our physical and mental well-being. Here we can exercise our muscles, breathe fresh air, raise our eyeballs up from our navels towards the distant horizon, and feel awed by the natural world. When we add a camera to our ramblings, together with a dash of inspiration, we may become so absorbed in the image-making process that all else is forgotten.

The all-important “dash of inspiration” is the spark we experience in response to something in the landscape. An obvious example is the wow of a fiery sunset that inspires so many people to grab their cameras. Others with more seasoned visual antennae will likely skip the sunset, but maybe fascinated by patterns in a freshly ploughed field, or feel intensely moved by a windblown tree, or amused by quirky road sign juxtaposed against a wilderness vista.

Whatever the external stimulus – the sunset, the field, the tree, the road sign – the important thing about inspiration is the internal response it triggers. It engages not only our senses but also our emotions, our intellect, our imagination, our aesthetic sensibilities. It focuses our attention and it creates – or, more accurately, it reveals – a meaningful connection between ourselves and whatever it was in the landscape that inspired us.

Why particular landscapes, seasons, weather?

But why does each of us respond differently to different landscapes and to different environmental conditions in those landscapes?

I have a friend who loves the forest. She can walk happily all day on a woodland trail. She feels comforted by the cradling canopy of trees. She stops to admire spring wildflowers, dappled summer sunlight or autumn leaves on the forest floor, birds flitting in the branches, a brook burbling through the ferns. And she makes beautiful photographs of these things; lush, gentle, sometimes dreamily impressionistic portraits of intimate forest scenes. When January comes, she laments the bleakness and settles into her studio for a winter of image processing.

Winter Birch trees shimmer with the colourful promise of spring and bring to mind the cycle of life, death and re-birth.

Whenever my friend and I hike together with our cameras, I enjoy the challenge of mentally disentangling her forest and finding compositions in it that work for me. For about half an hour. Then I hear myself screaming (quietly to myself) for the trail to emerge at a hilltop lookout. I want to see the sky. I long for a sweeping view. I need to escape the forest’s claustrophobic green. Later in the year, as autumn turns the green to brown and my friend wistfully winds down her image-making season, I am busy cleaning my kit, digging out my woolly socks and feeling the stirrings of real photographic enthusiasm again.

I have another friend who, several years ago, traded in his ultra-wide-angle lens, first for a telephoto, then for a macro lens. Within a few months, all the expansive landscapes had disappeared from his portfolio, replaced by exquisitely crafted images of landscape details; bands of colour in rocks, patterns in ice puddles, miniature forests in patches of lichen.

My friend attributed this transformation to photographic maturity. He became dismissive of classic, wide-angle images and scornful of the photographers who make them.

He has a point. The world is awash in this kind of photograph. After all, they’re relatively easy to replicate. All you need are the GPS coordinates for a scenic site, a few standard compositional elements, some flattering light, the right gear and a modicum of technique. It is also true that with photographic maturity we become better able to focus our attention (and lenses) on specific attributes of the landscape that inspire us, which certainly can result in tighter compositions.

But I am reluctant to throw the baby (the wide perspective) out with the bathwater (the over-photographed scene), because I believe it is possible to make expansive landscape photographs that are compelling, distinctive, and meaningful. But only by crafting them with our hearts, and in the right landscapes, not with a formula at some iconic location.

So, what is the “right” landscape? For my forest friend, the answer is obvious and makes sense for her personality, which is embracing and comfortable. For my macro friend, it is the miniature landscapes he comes across almost everywhere, which suits his meticulous character to a tee.

And the right landscape for me?

Where I live (in Nova Scotia, Canada) we call it the Atlantic Coastal Barrens. More generically it will be familiar to many as tundra, heath or moorland that is close to, and dominated by, the sea. The terrain is characterised by exposed bedrock, boggy soil, and stunted trees. The weather is moody, windy, cool and wet. The landscape offers broad views, framed by dramatic skies as storms roll off the ocean, and it comes ablaze every autumn as wild blueberry and other native bushes turn scarlet. At other times the views are obscured by fog, blizzards, or clouds of biting insects. It is a harsh environment, yet paradoxically fragile too, a place where only the toughest plants and creatures can survive, and yet are so easily destroyed.

Entanglement is my answer to a visual puzzle in the forest that challenged me – an organised person – to make order from the chaos of sticks.

Few people live on the barrens or even venture there, except to pick berries. Most see it as a dreary landscape. And often it is. But I have made my home beside Nova Scotia’s largest coastal barrens, and whenever I am away from it for more than a few days, I begin to pine.

It’s not that I refuse to travel. Like most people, I enjoy the excitement of exploring new places, and like most photographers, I find fresh scenery visually stimulating. However, unlike most, I rarely travel more than a day’s drive from home, usually to out-of-the-way places, always in the off-season, and never anywhere hot. The “green and pleasant land” is more appealing to me when it is frozen and snowy. Trees are more interesting when stripped of their leaves; beaches more alluring in the fog, without footprints. And my heart beats faster when the winter’s first snowflakes begin to fall.

So, the right landscape for me, both personally and photographically, is a so-called barren one. However, this still begs the question, why?

The answer seems so simple now. But it took me years (decades, if I am honest) to figure it out, or at least to say it aloud:

I am a loner.

This explains everything! My choice of home (rural, remote), my career (self-employed landscape photographer), my living arrangements (solo, albeit always with a dog and/or cat), where and when I travel (off-season, off the beaten track), my favourite seasons (winter, fall), my preferred photographic process (solitary, slow), and ultimately the photographs I make (moody, spacious, structured, minimalistic).

The details of my story are relevant only to me. You will have your own right landscape and your own story that explains it. My story boils down to a profound need for solitude, space and silence that I’ve learned are as essential to me as air, water and food. Out-of-the-way places, especially in wintertime, are my best hope of finding these things. I have also learned that – contrary to the prevailing opinion in our extrovert-dominated society – being a loner is not an affliction to be cured or a misdemeanour to be apologised for, but rather, a way of life to be lived. Enjoyed! How I wish I had known this all those decades ago.

The Long View encourages us to look farther and be curious about what lies hidden beyond the horizon.

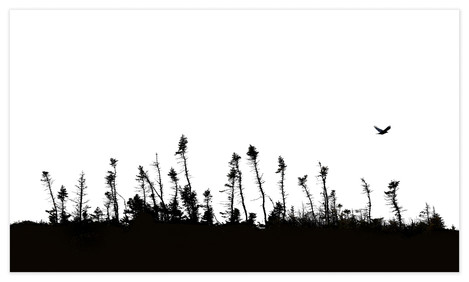

Just Passing Through is all that any of us is doing in this life, and the raven is often seen as an omen of death, so this image is an exhortation to make the most of it before we fly out of the frame.

The meaning of life?

In popular parlance, the “meaning” of life is synonymous with its “significance” or “value”, but scholars have been squabbling about the details for millennia. Countless volumes have been written on the topic, and still there is no consensus. Only a continuum of answers ranging from absolutist (life is intrinsically meaningful, courtesy of a god or Mother Nature) to relativist (life’s meaning varies with culture and individual experience) to nihilist (life is meaningless).

Certainly, as a lowly landscape photographer, I do not claim to have the answer. (You weren’t actually expecting one, were you?) However, my experience in making landscape photographs has led me to some conclusions about meaning in my own life. Days spent alone with my camera exploring wild places, responding (or not) to the scenery around me, feeling invigorated (or not) by the weather and excited (or not) about the subject matter I was photographing, and then, back at home at my computer, reviewing and evaluating how well (or not) my images express my experiences in the landscape. And, at every step, gnawing away at the question, why?

My conclusions are comforting. To me. For now.

I suppose I might describe myself as a usually-optimistic relativist-borderline-nihilist with respect to the meaning of life (what a wonderful business card that would make!). In plain English; I don’t see my life as inherently either meaningful or meaningless, and I am grateful for this ambiguity because it allows me to organise my daily life productively around projects that are important to me, cheered by the awareness that my life and its projects are, at best, of only minuscule and fleeting significance in the broader scheme of things.

So, in my photographs and writings, I work towards promoting environmental, physical and mental health and creating thoughtful images, at the same time confident that a heart attack or diabetes, an earthquake, climate change or, ahem, a global pandemic, will sooner or later wipe me – and the rest of the human species – from the Earth. And the Earth will breathe a huge sigh of relief.

The Ends of the Earth is where I live, at the remote eastern tip of Nova Scotia, and this is the view from my studio window as shafts of sunlight spar with storm clouds for dominance over the sea. The ever-changing skyscape here is a constant source of inspiration for my work.

Finding meaning through landscape photography

Whether my meaning-of-life conclusions leave you nodding your head in agreement, shaking it in opposition or scratching it in bewilderment, is not important. My conclusions don’t matter (except to me). What matters more widely is the process of finding them through photographing landscapes – experiencing, contemplating and visually celebrating scenery that is meaningful to us, and baring our souls, if only to ourselves, as we do so.

This process may be commonplace to more experienced members of our On Landscape community. But for those who are new to landscape photography, or just drifting along without much impetus or direction, it’s helpful to begin with a less daunting objective than “discover and express the meaning of life in my landscape photographs!” Instead, ask yourself some smaller questions – about images, about landscapes, and about yourself – and tease the answers from your subconscious with some simple(ish) exercises.

Exercise #1 – Looking at images

Look back through issues of On Landscape, or any other landscape photography magazine or book with quality images from multiple contributors, and collect (with scissors or screen captures) 25-50 images that “speak to you.” Try to pretend you are not a photographer as you do this. Just respond to the images personally and intuitively without over-thinking your selections.

Spread the images out in front of you, shuffle them around, and take a closer look. Are your selections mostly expansive landscapes or intimate ones? Is their mood generally bright, ethereal, sunny, or dark, contrasty, brooding? Are they sharply detailed, orderly and realistic, or dreamy, chaotic, impressionistic, abstract? Do any special favourites or trends emerge from the collection? If so, can you explain why (answering as a human, not as a photographer)? What is it about these images that resonates with your personality or your present circumstances and mental state?

Now repeat the exercise, but this time using your own photographs. You will find this more difficult because it’s impossible to avoid becoming side-tracked by the memories and emotions that are attached to your own images. Ask yourself the same questions as before, looking for trends in your images – and in your answers – that hint at their underlying meaning.

Exercise #2 – Looking at landscapes

Imagine the day (soon, we hope!) when we are all vaccinated against COVID-19 and free to roam the world again with our cameras. Open an atlas or Google Maps and pinpoint a few places you’d like to visit. And, since we are daydreaming, let’s assume an unlimited budget, lots of time, hassle-free logistics, and no purpose for your image-making apart from pleasing yourself.

Now, having plotted a holiday (or two or three), look at your list of destinations. Are they close to home, or far away and exotic? Have you been there before, or are they new to you? Are they tropical, temperate, polar, desert, forest, coastal, mountainous, tundra, grassland, wetland, farmland, urban, rural, pristine wilderness, or a variety of the above? What time of year would you visit? Would you spend the entire time at one destination, or try to see as many places as possible during your holiday? How would you travel: by aeroplane, a cruise ship, your car, a canoe, or backpacking?

This list of questions could go on, and of course, there are no “correct” answers. The point is to unleash your imagination and see where on the planet it takes you – and how and when, and most importantly why. What is it about these particular landscapes and style of travel through them that suits your character?

Exercise #3 – Looking at ourselves

Take your camera to one of your favourite landscapes (or, if you can’t visit a favourite landscape right now, mine your image archives instead) and create a photograph titled “Self Portrait” – without including yourself (or any other person) in the image. This means you must use features of the landscape itself to represent you.

The most obvious self-portrait for me would be a lone tree in a snowy field. However, at a deeper level, with all my human complexity, any of the images that accompany this essay could be a portrait of me. Taken together, they give a well-rounded picture of who I am, moody blues and all.

The same complexity is true of you, so it will be challenging to create a single image that adequately sums you up. Still, the process is worthwhile because it encourages you to point your camera very deliberately in both directions, outward to the landscape and inward into your soul.

This process of looking both ways is at the heart of expressive image-making. All landscape photographs, by definition, portray features of the external, geophysical world, but only meaningful ones enable glimpses into the topography and scenery of our inner worlds as well.

A Dark Horse was my companion during a picnic lunch on a remote hiking trail as a storm rolled in, reminding me of the value of friendship (even for loners) in times of trouble.

Self Portrait, Uprooted is a landscape I created in my studio from the upturned root of a wild rose, positioned on a piece of satin cloth – one of several such manufactured landscapes that reminded me of the wild outdoors and kept me sane during the COVID-19 lockdown. “Uprooted” was especially relevant as I was also moving house during the pandemic.

Meaningful landscape photographs?

So, how do we create meaningful landscape photographs? It is as simple – and as difficult – as adapting the process described in Exercise #3 above for every image we make.

Step 1 – Shut out distractions

When you set out to explore the landscape, turn off all your devices. No car radio, no podcasts on headphones, no cell phone. This frees you from the tempting distractions and notifications that bombard your life, and allows you to pay attention to the world around you.

A significant distraction for most people is other people. So, ideally, explore the landscape on your own, or, if solitude is too stressful for you, be sure to go with a kindred spirit who shares your approach and appreciates the benefits of companionable silence.

Also leave your camera in your bag – at the bottom of your bag – at least for now. Resist the pull of photographic expectations and practical motivations (getting a winning shot), and banish hyperfocal distance calculations from your head. If it helps, practice mindfulness meditation, focus on breathing, count your footsteps, whatever method you find most comfortable to silence your “chattering monkeys” so you can focus on the here and now, in readiness for Step 2.

Step 2 – Experience the landscape

Immerse yourself in the landscape wholeheartedly, paying attention to everything around you, not just with your eyes but with all your senses. Spend time, go for a walk, sit on a rock, have a picnic lunch, listen to bird song, feel the wind, taste the salty spray, smell the roses (literally as well as metaphorically), allow yourself to be mesmerised by the colours of periwinkle shells in a tide pool.

Once you have relaxed in the environment and taken it all in, make a (mental or paper) list of the elements you see – a “visual inventory” of the landscape.

Step 3 – Examine your responses

At the same time pay attention to your thoughts and feelings about these elements. Perhaps you find yourself brooding on your mortality under the weight of a stormy sky. Or dancing with delight as the snow begins to fall. You might feel kinship with a straggly old tree or a croaking raven. You may be overwhelmed with vertigo as you peer over a cliff edge. Delve into your responses and the connection they reveal between yourself and the landscape by asking the perennial question, why?

Step 4 – Translate your responses into images

Now, at last, pick up your camera and use your craft – working with light, colour and visual design – to translate your responses into photographs that are truly worthy of the experience you had in the landscape. That is, meaningful photographs. (Keeping in mind that if you show your photographs to me, they may mean something completely different, or nothing at all, unless my response to “your” landscape is similar – something to be wary of when releasing your images into the world!)

On the Way OutIt is my memorial to a beautiful old hay barn that, a year after I made this photograph, toppled over during a winter storm.

In a nutshell…

How effective we are at making meaningful landscape photographs is determined by our ability to forge, recognise and express meaningful connections between our lives and the landscapes we travel through. And this depends less on how well we know the landscape or the buttons and dials on our cameras, and more on how well we know ourselves. Enjoy the exploration!