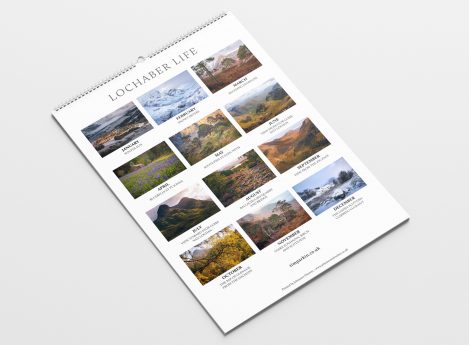

Thoughts on Planning, Design and Printing

Tim Parkin

Tim Parkin is a British landscape photographer, writer, and editor best known as the co-founder of On Landscape magazine, where he explores the art and practice of photographing the natural world. His work is thoughtful and carefully crafted, often focusing on subtle details and quiet moments in the landscape rather than dramatic vistas. Alongside his photography and writing, he co-founded the Natural Landscape Photography Awards, serves as a judge for other international competitions. Through all these projects, Parkin has become a respected and influential voice in contemporary landscape photography.

Despite the proliferation of online calendars, phone-based diaries and watches that remind you of important life events every few hours, printed calendars still have a thriving market. There’s something about having a display of artwork that you are prompted to change every month and that doubles as a place to scribble dates that digital devices can’t seem to replace.

From the photographer’s perspective, calendars fulfil two important tasks: one, compiling and editing a year's images in line with Ansel Adams’ idea that “Twelve significant photographs in a year is a good crop”, and two, creating a lasting record of those photographs that you can share with friends and family and perhaps beyond that.

Historically, creating a calendar was either a one-off affair printed on your home inkjet or an expensive production managed by a company specialising in litho printing, which meant at least a few hundred copies that you’d have to sell to recoup the printing costs. These days, digital printing has progressed so far that it’s cost-effective to print just a few calendars, and there are companies out there that can help you not only print the calendars but also prepare and produce them (find out more later in this article).

What Makes a Good Calendar

Although calendars don’t have to obviously reflect the yearly changes, it’s a nice idea to think about them in this way, even if the pictures don’t imply any seasonality.

For instance, in equatorial regions, there isn’t really a ‘normal’ cycle; the year is shaped by the drift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which moves north and south like a slow tide. When it sits overhead, the rains come. When it moves away, the skies clear, regions often end up with patterns like a long wet season and a short wet season or two dry seasons divided by transitional months.

Once you know that pattern, sketch it as a twelve-step cycle. It does not have to match the classic quarters of spring or autumn. You take the phases and distribute them across the months in the order they actually happen. If the long rains begin in March where you live, then March becomes your dramatic cloud-building month. April and May become months of deep colour, swollen rivers and soft light. If the dry season peaks in August, that becomes your month of heat shimmer, haze or crisp sea horizons.

For the southern hemisphere, January is a month of long days and summer heat. The beaches are full, and there’s a feeling that it’s an extension of the holiday period. This feeling continues into February and it’s only really in March and April that temperatures lower, ‘normal’ life tends to return, and outdoor activities become more adventurous.