The Varied Character and Light

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

God the Father, on a visit to the Valais in the company of St. Peter, offered the Valaisans who complained about the retreat of the glaciers and the aridity of their climate, to take care of the problem of water if they wished. St. Peter saw that the locals were hesitating, and encouraged them to accept the offer, telling them that God himself was a Valaisan. Was it this remark that got them thinking? In any case, they declined and from then on the Valaisans had to make up for their lack of water themselves. ~Rose-Claire Schüle, 1995, Les bisses dans les récits traditionnels (my translation)1

One of the fascinating things about the study of hydrology for me, as a hydrologist, is the long history of modification of natural sources of water by man. There are records of irrigation systems developed in China going back some 5000 years; there is the water supply system required for the Gardens of Babylon that appear in the Bible; there are the ancient underground canal systems in the middle east bringing water from the mountains to cities such as Tehran (called quanats in Iran, but also known in Iraq, Afghanistan and India); and the extensive aqueduct systems of the Roman Empire2. The “bisses” of the Valais in Switzerland are not of the same order: they are small man-made water courses that were used to channel water from the heads of valleys around the slope for supplying water to villages and alpage pastures. Some are still in use today. They are quite variable in size, slope and construction but all represent an enormous effort by both the men and women of the communes involved to both create and maintain them over long periods of time3.

Indeed, one of the wonderful things about the mountains of Switzerland is the way in which humans have, over centuries, made use of a challenging - if beautiful - landscape. Swiss bergers or armaillis still take herds of sheep, goats and cows up into the alpage pastures in summer, even where the animals may still have to climb several hundred metres to alpages without road access. They still produce cheese from the milk even in places where it is still only possible to bring the cheese to market on the backs of mules (some of the very best Gruyère and Etivaz4 cheeses come from such alpages in the Cantons of Fribourg and Vaud). They still use some amazingly steep slopes for the production of hay for winter feed for the animals, sometimes so steep that that the hay is still collected by hand raking. It is certainly true that some alpine pastures and hayfields have fallen into disuse and are gradually being reclaimed by trees, even at high altitudes. Despite all the new construction that is widespread throughout Switzerland it has one of the highest percentage reforestation rates in Europe.

But summers in Switzerland can be dry, and to maximise hay production and the number of cuts for winter feed that can be made, water is needed. This led to one of the most remarkable ways in which humans have modified the alpine landscape by the construction of the “bisses”, particularly in the Canton of Valais (or Wallis in Swiss German5). These channels bring water from a reliable summer supply (often glacier melt or a limestone spring source) to where it was needed, especially for the irrigation of hayfields, vegetable plots and vines. Without irrigation water, it has been estimated that the area has a water deficit of about 300 mm (or litres per square metre) over the summer.

Bisses are already documented in some of the first manuscripts surviving from the region in the 13th Century. The Valais historian Pierre Dubuis has put forward the hypothesis that up until the middle of the 14th century agriculture in the Valais was mainly producing cereals, which did not require irrigation. By 1350 the plague had decimated the local population, causing them to gradually abandon this type of cultivation. The agricultural land available was turned into pastures and hayfields which favoured the development of breeding livestock. The numbers of livestock increased dramatically and consequently the hayfields required extensive irrigation to produce the winter feed. One of those early channels, the Bisse de Riederi, which runs from Blaten to Ried-Morel near Naters, can be traced back to 1385 and was used until the 1940s.

The statistics describing the bisses of the Valais are impressive. The first comprehensive inventory was made by an engineer, Léopold Blotnitzki, in 1871 who found a total of 1536 km of constructed channels. A later survey by Fritz Rauchenstein in 1907 found 80 additional channels that had been constructed since 1870, and a total of 207 bisses with a length of 1400 km. A modern valley by valley inventory lists a total of 413 bisses7, with several of the tributary valleys having more than 20 listed. The longest listed is the Grand Bisse de Saxon at 29km which takes water from the Printse to serve the Communes of Nendaz, Isèrables, Riddes and Saxon and was constructed between 1863 and 1876. There are many others that are more than 10 km long.

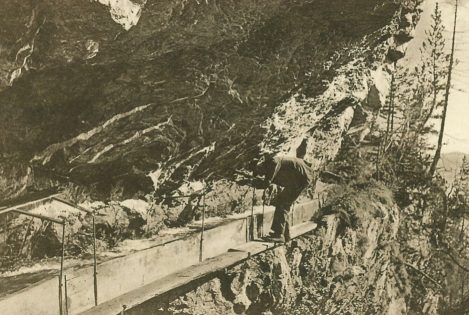

This gives some idea of the scale of the Bisse network in the Valais. What it does not convey is the nature of the construction. In some places, this was relatively simple, a shallow channel, with shallow slope, more or less following the contours around the valley to where the water was needed, upslope of the fields. Given the steep nature of the terrain, however, this was not always possible – there were sheer rock cliffs and steep sided gulleys to traverse, while some sections would need to be protected from rock and snow avalanches. In many places, the channel was constructed of wood and attached to a cliff face. In others, it was necessary to dig tunnels through the rock. Later construction and modernisations also introduced some metal channels.

Thus, because of the sheer effort needed in building and maintaining the bisses they represent a communal activity, which required significant degrees of organisation and regulation to make sure they worked and that the water was distributed fairly. Documents of contracts and rules of operation (and conflicts) date back to the 15th Century. Several communes constructed bisses in the 1400s, a time when the numbers of cattle requiring winter feed was increasing. Later, of bisses where the date of construction is known, only 18 were built between 1500 and 1800. This is in part due to a change to a colder and wetter climate when the glaciers were generally advancing (the period of the “Little Ice Age”).

In the 19th Century, particularly after 1850, there was again an expansion partly due to rewarming and partly due to an expansion of meat and cheese products with the arrival of the railway in the Valais, opening up new markets. In the early 20th Century there was again an expansion and a policy of modernisation, including some subsidies from the Government, with projects to replace some of the more spectacular cliff transversing wooden channels with tunnels. The spectacular Bisse du Torrent Neuf, with a tunnel through the cliffs of Prabé near to Savièse, dates from this time.”

However, the special nature of the bisses was recognised in 2023 in the listing by UNESCO as a World Cultural Heritage Site. This was preceded by some investment to create safe access for tourists to some of the more spectacular sites, such as the Bisse du Torrent Neuf and Bisse du Rho, including the construction of walkways and suspension bridges to allow the routes of those bisses to be followed more easily. Not all the bisses still carry water, or only along parts of their length, but many can be walked as there was always access alongside or over the channel to allow for maintenance and control of the distribution channels.

Some are more exposed than others, while those hanging from cliffs that have not been maintained can be downright dangerous (though for spectacular exposure try the Circuit of the 3 Bisses near Vercorin7 or the Bisse des Sarrasins south of Sierre8). Some of the old photographs showing men – and women – working on maintenance on the highly exposed sections are really rather scary.Some have been replaced with pipes to minimise the maintenance necessary. Some have simply not been maintained and run dry. There is a fascinating Bisse Museum in the village of Botyre not far from the Bisse d’Ayant and a web site with a map of the bisse networks and suggestions for walks along them9.

I have now walked many kilometres along different bisses (though not the most exposed….). They are always interesting in that they differ a lot in their characteristics (even along the length of a single bisse).

This is partly because of the fact that the flow is often relatively shallow so there can be reflected light from different coloured rocks (or, in places, wood or metal) on the bed, partly because of caustics due to refraction within the waves at the surface and reflections from the bed , and partly because they often run through trees so that there can be interesting patterns of light and shade on the surface. There can also be steeper waterfall-like sections where it was necessary to lose elevation along the route (such as in the Bisse du Petit Ruisseau near Champex-Lac below). As always, the challenge is to find a good composition with the light at hand.

The images that follow are a small selection of those taken in different bisses in recent years using a variety of techniques.

Bisse du Petit Ruisseau, Champex-Lac, Valais, Switzerland, 2024

Bisse d’Ayant, Anzère, Valais, Switzerland 2022

Bisse Vieux, Nendaz, Valais, Switzerland, 2020

References

- Rose-Claire Schüle, 1995, Les bisses dans les récits traditionnels, in: Annales valaisannes : bulletin trimestriel de la Société d'histoire du Valais romand, 1995, p. 341-350

- One of the interesting things about the Roman Aqueducts is that they are reported to have been designed without taking account of the velocity of the water in estimating their capacity, based on the contemporary writings of Vitruvius. While that is quite possible based on a history of engineering experience if the slope of the aqueduct is maintained at a standard value and if the lining does not vary too much in roughness, it does seem somewhat unlikely however given the all too obvious variations in velocity in natural rivers.

- More information about many of the bisses and suggestions for walking routes can be found (in English) at https://www.les-bisses-du-valais.ch/en/ (also available as a phone app). There are also books available such as Balades le long des bisses du valais by Gilbert Rouvinez, 180° Editions, 2020 (in French). There is an Association des Bisses du Valais with a site at https://bisses-encyclo.ch/association/ (in French).

- Etivaz cheese has an interesting history. In the 1930s, a group of 76 farming families producing Gruyère cheese in the vicinity of the village of Etivaz decided that government regulations were allowing cheesemakers to compromise the qualities that made good Gruyère so special. They withdrew from the Swiss government's Gruyère program, and started to call their own cheese, L'Etivaz. They founded a cooperative in 1932, and the first cheese cellars were built in 1934. A recent attempt to protect the name of Gruyère cheese to the valleys in Switzerland where it is produced failed in the United States where the term was held to be “generic” so that US produced cheese can also be called Gruyère.

- Valais consists of nearly all of the valley of the Rhone upstream of Lake Geneva (Lac Leman). The lower part of the valley is French speaking, the upper part, above Sierre, German speaking). The name bisses is mostly used in the central part of the valley; in the lower part the name “raie” is more common, and “suonen” or “wasserleite” in the upper Valais. Bisse appears to derive from patois variants on the word “bief”, a leet in English, and has been used since at least 1569. Similar irrigation systems are found in parts of France and Italy. In the Val d’Aoste they are known as “rus”.

- Gerber and Papilloud, op.cit.

- see https://www.vercorin.ch/en/P116454/things-to-see-and-do/circuit-of-the-3-bisses

- See https://www.vercorin.ch/en/V3881/things-to-see-and-do/in-summer-and-in-autumn/bisse-des-sarrasins

- See https://www.les-bisses-du-valais.ch/fr/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/01/physics-of-caustic-light-in-water/