Chapter 4: Retouching Prints By Hand

Michael Kenna

Michael Kenna (born Widnes, England 1953) is one of the most acclaimed landscape photographers of his generation with a truly global audience for his work. During Kenna’s fifty year career, he has held over 530 solo exhibitions in 40 countries, and his photographs have been the subject of over 90 monographs. To date, his prints are held in the permanent collections of over 110 museums worldwide. Kenna is particularly well-known for the intimate scale of his photography and his meticulous personal printing style. He works in the traditional, non-digital, silver photographic medium. His exquisitely handcrafted black and white prints, which he makes in his own darkroom, reflect a sense of refinement, respect for history, and thorough originality. Full Overview.

Luke Whitaker

Luke Whitaker (born Wimbledon, England 1978) is the owner of the award-winning Bosham Gallery which he set up in 2012, an online photography gallery specialising in the marketing and sale of limited edition prints and their framing.

He also teaches photography, and runs a business course programme for emerging artists. Luke has a lifelong passion for photography and collects photographs himself, particularly prints made between 1880-1920, which is his favourite period in the history of photography.

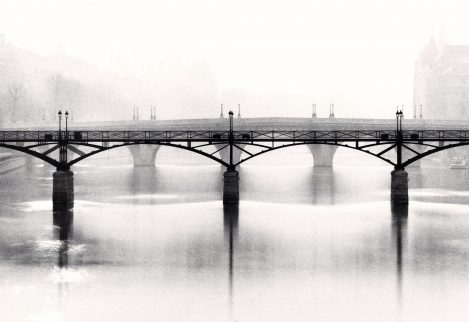

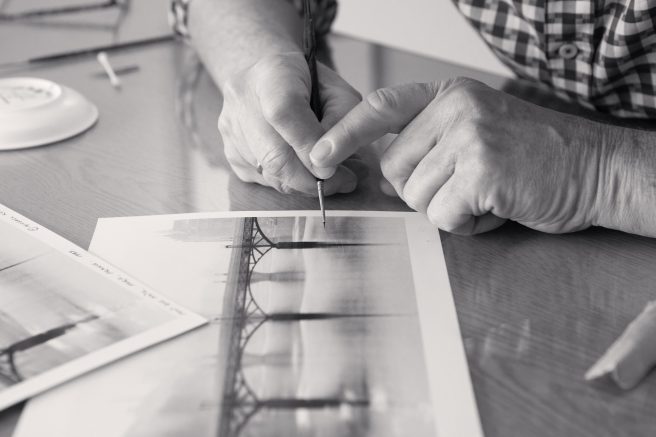

I watched Michael Kenna retouch a print by hand in my gallery in Bosham in 2019 during an exhibition of his New & Rare Works, and it was like seeing magic! The retouching process was so extraordinary that I joked with Michael that he had turned the gallery into a scene from Hogwarts. At any moment I expected Dumbledore to walk in! Unless one experiences retouching in person, I don’t think it is possible to appreciate the skill and patience required to make adjustments to the surface of a silver print with fine paint brushes and retouching dyes. The print in question was Pont Des Arts, Study 1, Paris, France, 1987 and a small speck on the surface of the silver gelatin print needed to be retouched.

It was caused by a tiny scratch to the negative. Before I share an extract from Michael Kenna’s print diaries, along with photographs of Michael retouching the print, it is important to explain the nature of retouching prints as part of the overall process of making wet chemistry silver gelatin prints. As Michael points out, it is almost impossible to make silver prints from negatives without there being some small white dust spots on the prints or the occasional black specks caused by scratches on the negatives. These have to be carefully retouched by hand with coloured dyes and fine retouching brushes. If a silver print is examined closely in the right lighting, it is possible to see how the image is embedded in the silver gelatin, rather than sitting on the surface of the paper as per a modern pigment print.

It was fascinating to watch Michael at work and see how a series of fine paint brush strokes darken areas within the print, and a scalpel blade lightens other areas. Every single print that Michael makes within each limited edition is compared and matched to an original Artist Proof. Because each single print has to be retouched by hand, each print becomes a unique work of art. Each dust spot might only take a minute or so to retouch by hand, but it is easy to appreciate how a whole print can take an hour or two to get just right.

Retouching requires a very steady hand, great patience and is extremely demanding on the eyes. Watching Michael at work, it was clear that I was seeing a master printer who had been doing this for decades.

Read the previous articles in this series:

- Chapter 1: Working With Film For Over 50 Years

- Chapter 2: Printing in the Darkroom

- Chapter 3: Grain, Cropping and Toning

Luke Whitaker

I think the retouching aspect of silver gelatin prints is greatly under appreciated. I have noticed some very beautiful prints, with quite poor retouching, which I think is wholly unnecessary.

Retouching helps the viewer look into and around a print. It is also another option to edit out areas we do not want to attract attention to. Most of us are now familiar with digital retouching. The principles are the same with physical retouching, albeit it is a lot more time consuming. As mentioned in earlier chapters in this series, our eyes generally move towards bright areas.

White spots, therefore, force us to remain on the surface of the print, which effectively destroys the three-dimensional illusion of a photograph. Certain highlights can also often obstruct the flow of a print. I look at prints from both close up and at a distance to see if there are spots or areas of highlights which can be helped by being retouched out.

Retouching dyes come in different colours and need to be matched to the different areas of the print - warm in the highlights and cold in the shadows for my prints. Occasionally, black spots appear on the print from tiny holes in the emulsion of the negative. These are a bit more troublesome and need fine etching with a scalpel blade.

Retouching a single print can take anywhere from minutes to hours and every print needs to be retouched. Good retouching should not be immediately visible. Indeed, if a viewer comments on the ‘excellent retouching’, you know you haven’t done a very good job!

While printing for the great photographer, Ruth Bernhard, I learnt a little trick that is not mentioned in most technical descriptions of the print making process: steaming. After a print is fully retouched, I boil a kettle of water and let the print hover over the steam. The gelatin subsequently swells and absorbs the retouching agent to the point that the two surfaces become one. Good retouching ‘should’ become invisible!

A good example of the principle of retouching is the image Reflection, Big Sur, California, USA. 1979. The original negative is 4x5 inches, and all resulting prints are covered in white dust specks. My fault entirely, as I had just purchased the Graflex Speed folding camera and, in my enthusiasm, did not even think to clean the film dark slides before use. The result is 3+ hours of hand retouching on every print.”

4 Studies of Michael Kenna

Retouching Pont Des Arts, Study 1, Paris, France, 1987, in Bosham Gallery in 2019 © Henry Wells:

Retired Negatives by Michael Kenna

Retired Negatives by Michael Kenna is an online exhibition of his most collected work over the past 50 years, featuring the remaining Artist Proof editions of photographs whose numbered limited editions have now sold out.

The collection is a chance to acquire a print from editions in which the negative has been formally retired within Michael’s archive. All of his silver gelatin prints are still made by him personally in his darkroom at his home in Seattle. The online exhibition is hosted by Bosham Gallery and can be seen at boshamgallery.com until 17th December 2025.

‘Machine-made pigment prints are of excellent quality, but, at least for me, silver prints remain the gold standard in photography,’ says Michael. ‘It is also comforting to know that these prints are made to archival standards, which means they should well outlast me and collectors. I keep records of every print I have signed and editioned, and have prints in my own collection, which I made 50 years ago. They are as good today as when I first made them.’

To accompany Retired Negatives, and to celebrate 50 years of darkroom printing, Bosham Gallery’s Luke Whitaker is presenting a five-part series of chapters from Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries in collaboration with Black & White Photography Magazine.

Please visit boshamgallery.com to see the online exhibition and to read Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries.