Balance of purpose and practice

Amanda Harman

Amanda Harman is an award-winning photographer, based in the South West of England. In recent years her work has focused on landscape and place, from the garden of a country house to the watery landscape of the Somerset Levels and the steep scarp of the Cotswolds near Stroud.

“Time spent walking and retracing routes across the landscape, in all weathers and seasons, is key to my current process and way of making images. By observing a place for months, and often years, I seek to reveal the unseen and the insignificant, and by quiet observation elevate the beauty of ordinary and overlooked places.”

Her work and approach have been recognised by a number of awards. She was the winner of the Sony World Photography Award for Still Life in 2014 for the ‘Garden Stories’ series and shortlisted again in 2018 in the Landscape category for ‘A Fluid Landscape’. ‘Garden Stories’ also won the Critical Mass Exhibition Award in 2016, with a solo show at Blue Sky, Centre for the Photographic Arts, in Portland, Oregon. ‘A Fluid Landscape’ was published as photobook in 2018 by Another Place Press and exhibited in a solo exhibition at Gallery at Home in 2020. ‘Garden Stories’ was published in the Field Notes series by Another Place Press in 2020.

Amanda has worked on a range of commissions, residencies and projects for galleries, museums, charities and commercial clients. Her work has been exhibited widely in the UK and internationally and is held in a number of collections, including the V & A Museum, London.

The Frith Fields lie in the south Cotswolds, and have, through care and steadfastness, been returned to native meadow. My project began with a simple idea: to photograph the fields through the seasons, and to let repeated encounters with this place reveal new ways of seeing it, and maybe to create a book.

Beneath this plan, there was also a looser purpose: to understand how one lives and works with place. Emma and Matt’s stewardship of the fields was a vital part of this. Their years of patient restoration, their belief in “doing the right thing” by the land, and their generosity in sharing knowledge gave me a strong foundation.

Alongside making the photographs, I kept a written journal, usually penned back in the studio using the images from each day to reflect on the thoughts, feelings and sensations I’d experienced. Each entry was both an anchor and a prompt, which helped me to understand and acknowledge how much the fields resisted being contained by the frame, and how my methods would have to adapt.

Inspiration

The inspiration for the work came from multiple sources. Research revealed that the UK has lost 7.5 million acres of wildflower meadow and flower-rich grassland since the 1930s1. 1400 insect species rely on meadows for their survival, and these plants and insects help to maintain a healthy ecosystem. Meeting Emma and Matt, who had devoted years to restoring the meadows, gave me both context and motivation. Their stewardship spoke of patience and persistence, and Emma’s references to Ikigai - the balance of purpose and practice - and to Katherine Swift’s The Morville Hours situated my own efforts within a wider tradition of living with land.

Alongside this, exhibitions, reading and conversations informed my thinking.

The voices of others were important, Matt’s insights and knowledge of the wildlife in the fields, his sighting of a stoat dragging a baby rabbit, bigger than itself, across the bottom field or finding a newly born fawn nestled among the long grass—all these grounded my practice within a living network of care and observation. Later, my friend Shelley’s reflection that my work carried something of the “pastoral sublime” reframed what I was doing. Was my attention to this landscape simply about beauty? Or did it echo wider crises—climate, political, social—that haunt our times? Inspiration, I came to see, is never solitary. It is a conversation between place, people, and understanding.

Highs and Lows

There were auspicious moments when photography and place aligned, if briefly. Early morning mists rising from the valley offered fleeting drama; frosted seedheads glowed under low sun; the appearance of blackthorn blossom against a grey hedge brought a clarity where form, light, and season cohered into an image.

The low points came in quieter, more insistent ways. The fields sit on the side of a steep valley; in winter, the sun rarely lifts high enough to illuminate the fields. In summer, the opposite harsh midday light flattened the abundance in the fields into visual confusion, making it nearly impossible to render with any subtlety. There was the impossibility of capturing grass snakes, or of making butterflies feel as alive in an image as they were in flight. And at times the meadows felt constraining: three fields, always the same boundaries, the sense of repetition that made me long for the unstructured wandering which is my usual way of working.

Shifting Process: From Image to Material

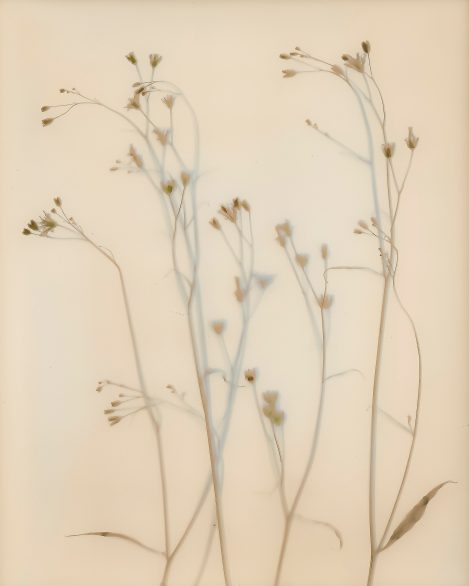

The recognition of the limits of what I was able to do with the camera marked a turning point. So rather than photographing what I saw, I began to work with what I could touch. Collecting and pressing plants became a new form of image-making. At first, this was a nostalgic act, and one that echoed early photographic processes. Like a negative, pressing flattens, fixes, and preserves—pigments fade, colours shift, chlorophyll recedes. What remains is both presence and absence: the form intact, but the life altered

.

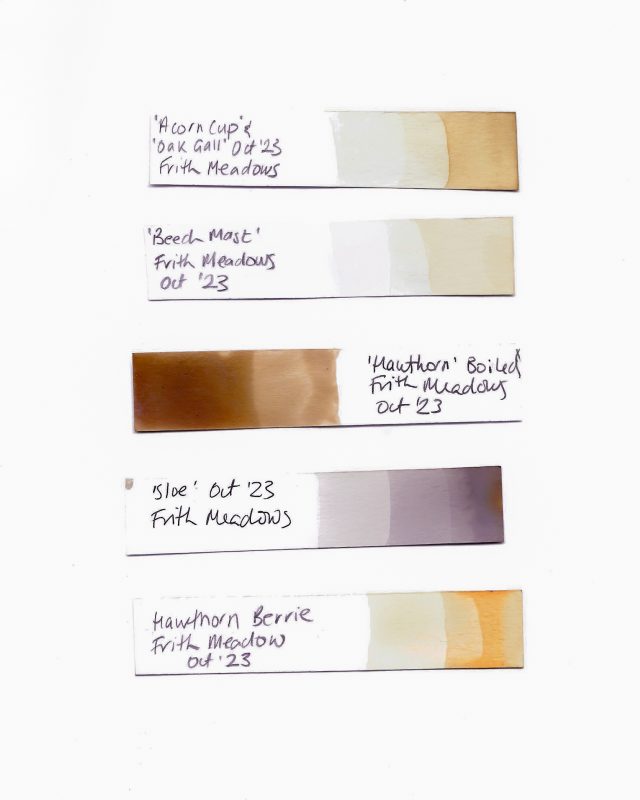

Making pigments followed, I became fascinated with the idea of making inks from the very matter of the fields—plants, soil, stones. I did a short workshop with Lucy at London Pigment, who generates pigments from materials in the landscape that reflect the city, and her relationship with colour and place.

Inspired by Fabian Miller, I began placing plants and seeds from the fields directly onto photographic paper and exposing them to sunlight, creating lumen prints. These negative images were formed not only by the shadows of the plants but also by their chemical reaction with the paper, which formed soft auras around the images of the plants. I later scanned these negatives and converted them into positives. The originals remain unfixed, tucked away in a dark drawer in my studio, like the flowers and grasses they depict, they are ephemeral, fragile —still sensitive to light, and always vulnerable to change.

These processes remain photographic in spirit, but without the lens — an engagement with light-sensitive materials, with chemistry, with the physical traces of place. Each pressed flower, pigment and lumen print felt like an attempt to bridge the gap between presence and representation.

Insights

In the end, the Frith Fields became less about making successful photographs and more about learning what photography cannot do. The camera faltered where the fields were most alive. But in that I discovered other ways of working - pressings, pigment, lumen printing — that deepened the project rather than diminished it.

Looking back, the Frith Fields taught me that photography is as much about failure as success.

I made the work by following my nose, letting process lead the way, and found myself with a collection of disparate pieces: photographs, pressed flowers, landscapes, still-lives, and ink. At first, drawing these fragments together into a coherent whole felt impossible. Then I spoke again with Iain at Another Place Press — so generous with his time, ideas, and skill. We talked about the possibility of a small publication in the Field Notes series, and I sent him a mass of files. What came back was nothing short of transformative: a design that wove together the photographs and lumen prints, interlacing them so they began to speak with one voice. Somehow it captured that elusive sense of the fields’ vitality. From this starting point, I can now imagine a larger publication, one that draws on all the elements of the process. Thanks to Iain’s intervention and design expertise, I can see the work differently — as something whole, and alive.

Final thoughts

‘The Frith Fields’ began as a simple plan to document three fields, but it became a reflection on the limits and possibilities of photography itself. In turning to camera-less processes — lumen prints, pressed plants, pigments — I found ways to work that felt more intimate and connected to the life of the fields. These processes became the breakthrough of the project, transforming limitation into possibility, absence into presence. They reminded me that photography is not only about what the lens captures, but also about how light, chemistry, and material can speak together.

In the end, the Frith Fields were less a subject, more a collaborator; they resisted simplification and offered, in return, a richer way of seeing.

The Frith Fields by Amanda Harman, Another Place press