Featured Photographer

Pep Ventosa

Pep Ventosa’s work is focused on an exploration of the photographic image; finding new visual experiences in photography. His photographs have been exhibited in the U.S., Canada, Australia, Asia, and throughout Europe, and received honors from the Prix de la Photographie Paris, London International Creative Competition, American Icon Competition, International Color Awards, Photolucida’s Critical Mass, XVII Firart Penedès and other art and photography competitions. A Catalan, Ventosa was born in 1957 in Vilafranca del Penedès (Barcelona), Spain and currently lives near San Francisco.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

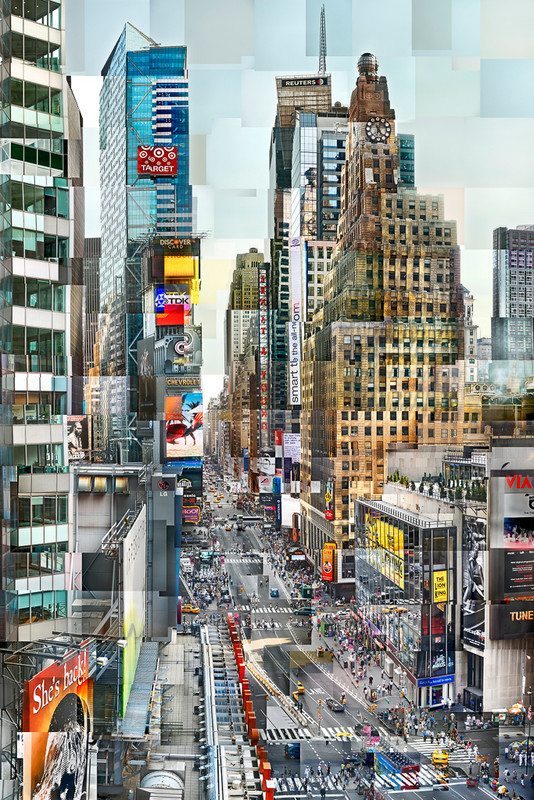

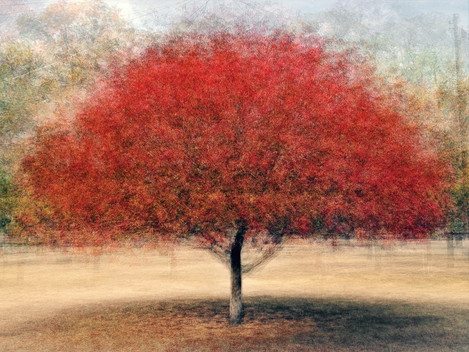

Multiple exposure images have increased in popularity over the past few years. You may have come across a technique called ‘in the round’ where a large number of images taken at intervals around a central focus are combined in layers to produce an image that is more akin to a drawing than a photograph. For this issue, we’re delighted to talk to Pep Ventosa, whose photographic compilations of trees, among other subjects, have inspired many others to try this technique.

Can you tell readers a little about yourself – your education, early interests and career – and the environments that have shaped you?

I grew up in a farmhouse in the Penedès wine country, south of Barcelona, attended school in the city of Barcelona and studied Tourism as a career. Franco ruled Spain under a fascist regime until I was 18 years old. They were scary times, with limited freedoms and a lot of repression. My reaction and shelter to that environment were through music and photography. I played drums in several bands, I guess as a form of personal resistance, and viewing photographs from the free world became like windows for me, something to aspire to and dream about. Through magazines and books, I discovered images of the hippie and social movements of the late 60s, amazing portraiture, beautiful pictures of remote exotic places and historic and archaeological sites, and photos of live concerts of bands which were impossible to attend in Spain at the time. Magazines like Life and National Geographic also served as an education for my eye, a great source of photojournalism and landscape photography. At the time, it was all a light in the darkness, an anchor to the world.

How and when did you first become interested in photography? You went to art school but didn’t take to the darkroom. Yet you retained an ambition to work as a photographer?

I’ve been fascinated with photographs as long as I can remember. I think every photograph is interesting. They hold some illusionistic quality. In 1967, my family received a camera as a present from friends in France. It was an Olympus Pen, a half-frame fixed-lens viewfinder camera. I was 10 and that object was like a magic tool. I took pictures of our farm, the family, my dog; all black and white. Although I wasn’t especially excited with the results as they didn’t look quite like the magazine shots. As a young teen, I became a drummer and spent many years thereafter consumed with music, but my interest in photography remained. I bought my first SLR in my 20’s and went to art school to learn more about it. There I discovered that the click of the camera might start a photograph, but it didn’t end there. You could adjust and perfect it in the darkroom. Two steps that can make a world of difference. Now, when I take a photograph I feel it is the beginning of something rather than the end, as it was in my early days. And in the digital darkroom, I feel I have infinitely more possibilities at play.

What styles of photography and subjects interested you initially? From where (or whom) do you draw inspiration?

From a very young age, I was attracted to archaeology and old architecture. I loved seeing ancient ruins, castles and cathedrals. It was a way to experience history. I once aspired to be an archaeologist. Also growing up in the countryside, not far from the coast, I learn to appreciate nature and the landscape.

How important was your move from Barcelona to San Francisco Bay, and the time at which you moved? The digital revolution in a sense set you free to become the photographer you wanted to be, and you were in the right place at the right time.

Moving from BCN to SF in 1999 was the best move in my life. First, because I married an extraordinary person, my wife Jackie. Second, because SF is a highly inspiring city, as beautiful as few places I’ve been, with a pulsating art scene where my love for photography was reinvigorated. And third, because the digital revolution was taking off and with it, I found the tools to achieve my photographic vision, the photographic image as a mean to create new visual experiences rather than to reproduce the world.

Beyond developing an individual approach, what do you consider has particularly helped you to establish yourself? (e.g. reviews, exhibitions, social media, competition success).

Do you think that the popularity of “In the Round – Trees” is in part as a result of society’s increasing disconnect from nature? Trees are there but most of the time we are looking past them?

Trees have always had a profound symbolism: rooted in the earth, projecting to the sky. They nurture life giving us food, shelter and the air we breathe. They are symbols of strength, wisdom, and protection, and they are simply beautiful. Maybe our urban and stressful life, detached from the long history of humans surrounded by forests and trees, produces nostalgia for them. Hanging a picture of a tree in a wall may bring some sort of comfort, some feeling of shelter and security; a connection to our past. With the Trees in the Round series, I’m also trying to show trees in a new way. By blending a group of shots taken while walking around one tree, I like to give the tree a starring role, showing it from all sides at once, with the background falling away into abstraction.

How important is the habitat, the background to your images? As more people are absorbed in their technology, their perception of the environment around them lessons.

As with the Trees In the Round, I have other series such as the Carousels in the Round and the Street Lamps where by overlaying multiple images the main subject is highlighted and the background is transformed into abstract shapes and colour fields. I see your point about this becoming also true of the way we see. But I believe that even though people are spending less time looking around and more time on their screens, it’s also true that we are all taking more pictures than ever before, with cameras, phones and drones. And while much of it is driven by the human necessity to capture the things we like and to say “I was there, I saw that, I did that,” along the way we’re also seeing things in that imagery in ways unseen before. So at the same time, our understanding of the world and the environments in which we live is expanding.

How do you feel about the others adopting – aping even – “in the round”? Is imitation flattery or do you wish they’d go find their own way of looking at the world?

When I see close imitations of my Trees in the Round without a mention of the source of inspiration, it doesn’t feel good, not unlike when a musician recognises her melody in other’s music. (Although it may be a coincidence, right? Ideas are not necessarily exclusive.) On the other hand, when it is used as experimentation by other photographers who are trying to ultimately achieve something different, I am flattered to have inspired them and influenced their creative processes. Certainly, I’m not working with something that is completely new and exclusive; the question is to make things your own way, finding the originality. My wish is that my photographic explorations inspire others to find their own voice, their own style.

You’ve previously defined ‘originality’ as ‘repetition with judgement’ but there will always be some who see repetition as their shortcut to success?

Repetition does not necessarily mean to copy; it means imitation, inspiration. It is a concept rather than an actual action. Finding new significance to an existing thing is to find something original. Nothing comes from nothing. It was Voltaire who said: “Originality is nothing but judicious imitation. The most original writers borrowed one from another.” We are all part of the very old tradition of creating images: drawings, paintings, sculptures, photographs…and that surely has a profound influence on us. Through repetition and imitation, as concepts, we may find our unique voice, ergo be originals. Something especially difficult in photography, I think.

How important is it to differentiate between photography as a technique and as a medium? It’s all too easy to stumble at the first and not appreciate or explore the possibilities of the latter.

Photography is one of the broadest mediums we know. It has immense potential to reveal information, to show us and to help us understand the world. Photography is technology, science, art, memory…and with computer-mediated technologies, like the ubiquitous smartphones, it is a universal language, a substitute for words. It’s a gigantic playground and we, the players, can arrange the game with our own rules, either for the pleasure of technical fascination, for the search of beauty, or for the unavoidable urge to tell a story. We cannot embrace the whole universe of photography, so our unique chance is to focus on the functions of the medium that speaks to us. I think it’s important to know about the medium and its history, as a way to find your place in it.

Digital has freed us up to explore, to play even, perhaps in the same way that photography allowed painters to move away from photo-realism?

Good point. I’m positive that the impact of the digital revolution in photography has exponentially expanded its language, in the same way, that, on another level, it is now reclaiming old analogical, almost obsolete, techniques.

The advent of the pixel and the ease of its manipulation is also changing the credibility that once was associated with photography. It’s not crazy to relate all of that to a photographic departure from realism and the documentary properties to explore new territories like some painters did almost two centuries ago when they felt that realism was perfectly done by photography.

The internet has increasingly become a resource for you? For compiling and creating the new interpretations of well-known views and for series such as Street Rhythms?

Since the inception of the Internet we kind of live in two worlds: the real one and a virtual one. I find them both supplementary and inspiring. The virtual world has an added value that is its novelty, is a new place to explore with lots of creative possibilities. On top of the more than one billion photos uploaded to the web every day, mapping software is robotically capturing 360-degree views and a near seamless mirror-like image of the world. I like the idea of repurposing this data-driven imagery and giving it artistic composition. The Street Rhythms and other series are an example of that.

To what extent are you reflected in your photographs? Your musicianship and sense of rhythm, and what you described to another interviewer as a chaotic, spontaneous, personality?

We project ourselves in our actions. What we do, somehow define who we are, right? In that sense, I guess my photographs, as well as my work methods, reflect who I am. I usually work with several projects at once, jumping from one to another. Most of my series are ongoing. I’m always exploring new ideas and making experiments to see if I hit something of interest. There’s a lot of spontaneity involved rather than a plan.

My musical background and my love for music must have an impact in my work too. I see rhythm, harmony and dynamics in my images. Time, indispensable in music, is somehow also in my work: the images are intriguing to the eye and there’s a need of time to inspect them. As for sound, the other essential characteristic of music, I sense it through the feel of vibration of the multiple images at play.

Yet what you do requires a degree of patience and persistence – layering and compositing are not for the faint-hearted.

People who know me would describe me mostly as quiet and patient. That serves me well in my work. My images are constructions made of multiple photographs and a lot of trial and error. It requires some persistence to make them work. I feel more like the painter that sees his painting progressing little by little. It is a process that I enjoy.

Do you see your work – your technique and the resulting images – as being in part a response to the immediacy of much photography? An antidote even: the time you spend creating the images but also in making the viewer work harder too?

One thing I miss from the film days is the idea of the latent image; the image that floats in the film once it has been captured and before it is processed and printed.

You’ve said too that you’re trying to mimic the way that our sight works, and you’ve also mentioned collective memories?

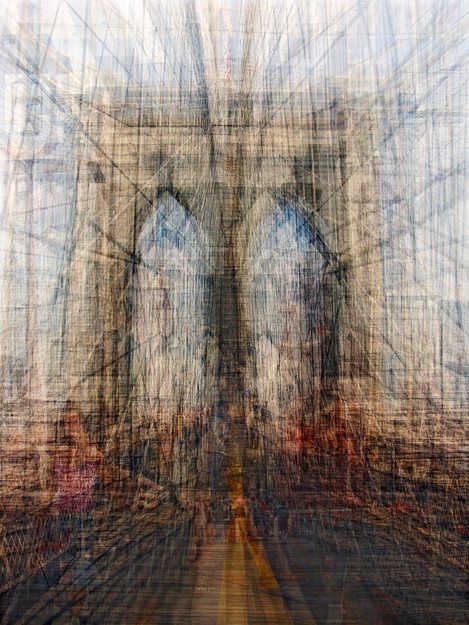

The notion of a collective memory arises from my Collective Snapshot series. It’s an homage to the most enduring form of photography: the snapshot. Everyone who goes to Paris takes a shot of the Eiffel Tower. I adapt, overlay, and rework those found shots to combine them into new representations of the places we’ve collectively been and seen.

As for mimicking the way we see, my Reconstructed Works series is a deconstruction and reconstruction of various scenes. I first capture something in smaller puzzle pieces—sometimes 20, sometimes 200—and then rebuilt it in my digital darkroom. I don’t use stitching software; rather I do it by hand, or mouse if you will, positioning and processing every single piece at my will. That process mimics how we actually see: the eyes are constantly focusing on the specific details and elements of what’s in front of them and the brain then processes that visual information making the reconstruction so we perceive the world around us.

What else interests you photographically? Are there subjects or themes that you are keen to explore further in future?

I’m intrigued by anything photographic. I love looking at photographs, reading about them, seeing them at exhibits and in books. I like the idea of taking familiar objects and finding ways to present them in a new light. I’m interested in the interrelationships between photography and painting. I like old cameras and have a ridiculously large collection of them that I imagine will one day inspire new works. In short, I have my head and hands in a bunch of new ideas and experiments and no idea which if any might be realised—we’ll see—but I look forward to the exploration.

Who do you admire? Is there anyone (a photographer, amateur or professional) that you’d like to suggest we interview in future?

I love Richard Misrach’s work. The landscapes of his ongoing series for 40 years, Desert Cantos, are mesmerising, not only beautiful but with a profound narrative about the relationship of man and landscape.

Thank you for the opportunity to answer your insightful questions and share my story with your readers.

Thank you too, Pep, I’m sure our readers will enjoy your words and images.

You can see more of Pep’s images on his website.