A photography expedition

Judy Sharrock

Judy is a late and recent convert to the joys of photography. She lives in the New Forest but also has a house in Mellon Charles on the North West coast of Scotland, so both areas provide plenty of scope to develop her landscape skills in two contrasting but beautiful parts of Great Britain. (Author image taken by Julia Moffat.)

In the early autumn of 2019, I was privileged to be one of twelve photographers, led by Anthony Spencer and Joe Cornish on a photographic “expedition” to the North East Greenland Coast.

The inaccessibility of this area, the distance north and the consequent absence of any human activity or infrastructure, makes it a very rarely visited part of the globe. It was truly a small expedition, even the crew and the other guides on the ship, the RV Kinfish, had not crossed the Greenland Sea from Svalbard, or indeed ever been to many of the places we explored.

I had poured over the maps of where we were going and looked at Google Earth. I wanted to see the icebergs, the glaciers, sea ice and if we were lucky polar bears, muskox, arctic hares, seals and whales.

The two day crossing from Svalbard was rough and grey. We were thrown about our small icebreaker by a sea rolling us against the direction we wanted to go. We limited our movements about the ship to a minimum and processed the images we had taken in Svalbard before heading for Greenland.

We woke up on the third morning, aware that Kinfish was calm in the water. Rushing up on deck we saw a quiet sea, the low Greenland coast in the distance and a massive, beautiful iceberg full of curves and topped with a row of kittiwake. From then on almost every hour on Kinfish brought amazing sights and experiences that I don’t think anyone on board will forget in a hurry.

We were lucky and saw many polar bears, the first on the morning we arrived in Greenland. The following day we experienced the sea ice. We also saw other inhabitants of an autumnal Greenland from time to time such as muskox and arctic hare, a variety of seals and whales and walrus. We saw massive young icebergs, several kilometres long. We saw smaller old decaying bergs sculpted by the sea and wind and all sizes and shapes in between. But there were two other things that captivated my attention, particularly when we went ashore and when we were sailing through the rarely visited fjord systems.

The first was the tundra. The word “tundra” derives from the Finnish word tunturia, meaning barren or treeless hill but this may be a little misleading. Before heading north I had started to read “Arctic Dreams” by Barry Lopez. I had not got very far into the book, but one small section about tundra vegetation stuck in my head;

“Much of the tundra of course appears treeless, when, in many places, it is actually covered in trees - a thick matting of short, ancient willows and birches. You realise suddenly that you are wandering about on top of a forest.”.

The short Arctic summer (and others factors described in detail in “Arctic Dreams”) creates a low growth of vegetation and of course, early September was autumn there, so this low plant life was sporting spectacular colour. I was therefore prepared for the low “forest” but not the autumn colours or the sheer delicacy and beauty of the ground.

There is an image by Paul Wakefield in his book “The Landscape”, shot in Culbin Forest which has always inspired me to remember to look down as well as ahead. It is of the gentle forest floor covered with pine cones and needles, stones, lichen and twigs. At first glance, it looks like a random selection of the area, but on a closer look, you can see how carefully Paul has selected a part of the forest floor where the components created a natural, balanced composition, so the selection is not random at all.

There is also a Paul Strand image of the ground which has always stuck with me. It is just called “Seaweed” (the one on page 58) in his book “Tir a Mhurain” about South Uist. It is a simple mono image of thin, string like seaweed tangled in the sand on the beach. In many ways, on its own, it is an unremarkable photograph but the concept of making an image from something so simple definitely left an impression on me. These two images (and many others) made me realise that the ground beneath your feet can be as interesting and beautiful as the horizon.

The second element which I had known about in theory, but was unprepared for, was the geology. It was, to quote our Canadian guide Beau Pruneau “insane”. In the fjords, up to 2000 metre high mountains, drop vertically into the water, revealing the stripes, patterns and colours of the geology. I know next to nothing about geology and am generally happy to appreciate the visual results of age, geological activity and weather, rather than understand the nuances of how and when that was all created1.

That said it was clear that each fold in the rock and each stripe and pattern was a chapter in the history of the Earth. We were able to visit the area, only in the small window of time during the year when the fjords were accessible. We also knew that within a short time after we left the whole area would return to winter. The feeling of timelessness created by the geology and the mountains seemed at odds with the idea that within a few weeks, winter would make the whole region look totally different. Sometimes it was hard to believe we were somewhere real on the planet and not some sort of imagined film set.

Photographically we had three scenarios. The first, and the one we spent most of the time doing, was shooting from Kinfish as she cruised the coast and the fjords. The second was shooting from the Zodiacs and the third was shooting ashore.

Shooting from the Kinfish and the Zodiacs was totally out of my comfort zone i.e. all handheld. Having no nice reassuring tripod threw up a lot of technical challenges.

I took two camera bodies. A Fuji XT3 with the Fuji18-135 which is the lens I use most of the time. I also had a Fuji X-H1 (which has image stabilisation which the X-T3 does not) set up with the Fuji 100-400. This meant I could move from one to the other like a wedding photographer and it kept life simple. Images come and go fast when shooting from Kinfish and the Zodiacs so there is little or no time to change lenses in any event.

It was a constant juggling of exposure, aperture and iso. Looking back through my images there is wide variation in all of these.

But I also remember one evening shooting a sea bird perched handily on a perfectly shaped chunk of sea ice in fading light and getting very frustrated with the decisions and compromises I was having to make. Joe Cornish was with me and said words to the effect that I should not compromise the creativity of the images in search of technical perfection. This struck a big chord with me and felt like a licence to stress less and just enjoy where we were and enjoy creating the images.

The first place we went ashore was called Mygbukta, also known as Mosquito Bay. It was marked with a single wooden house and signs of occasional human presence. It is the site of some Greenland history, in particular attempts by Norway to steal Greenland from the Danes.

On this particular day, separate polar bears had been sighted from Kinfish either side of the house. They were far enough away for us to go ashore but for a shorter visit than planned and with less kit in case a hasty retreat was needed, which meant no tripods. Looking back at my images from that day now, I am amazed at how calm the sea is on this exposed eastern coastline far north of the Arctic Circle. There were no waves or wind. The sea was a calm millpond lapping silently on the stony shoreline without disturbing the fragments of ice on the beach.

This part of the coast had a gentler landscape than we were about to experience in the fjords, but autumn had turned the ground into an orange and yellow coloured carpet. This was my first step onto the Greenland tundra and the infertile ground at my feet looked so different from anything I had ever experience before. Some areas looked cracked and bare, others boggy from the melting permafrost, but on closer inspection, a lot of the ground was covered with tiny lichens and mosses and small areas of ice.

In one place I was stopped short by a small bone which was half buried in the ground. It looked as if the earth was slowly absorbing it. A full circle of life. This proved difficult to photograph because of the contrast between the bright white bone and some white lichen with tiny dark intricate shadows. I love this image because of what it represents rather than, despite my many attempts at processing it, for its beauty. I have thought about monochrome, but for me that would take away an important element, its colour, even if it is a slightly sludgy green.

By the shore, the gentle wind had blown grasses, leaves and feathers into an almost perfectly arranged “still-life” and this is another of my favourite images from the trip. The soft colour palette seems to match the gentle curves of the feathers and the small leaves had dulled to greys and browns, some with silver veins and hairs. There were fine roots and driftwood and other general autumnal detritus. The gentleness of this image was also hard to reconcile with the stark Arctic landscape around it and the harshness of the half buried bone.

This first visit ashore had really brought the tundra to my attention and it had absorbed me for the whole of the short time we had to spend there before returning to Kinfish moored out in the bay.

One of the most astounding places we visited was a fjord right at the end of the Kejser-Franz-Joseph Fjord system. We arrived first thing in the morning and we were all instantly out on deck to wonder at the sight we saw. It was a totally calm silent morning, no wind and only the wash of Kinfish disturbing the water. Ahead of us was an iceberg “graveyard”.

By then we were getting used to shooting from the Zodiac, but with seven of us in each of the small craft, trying to find the space to make the shots we wanted required a good degree of good humoured give and take with each other and a lot of help from the guides in charge of where we went and at what speed. It was quite the most intense experience as we were all aware that this was something quite special.

We then went ashore where we found muskox trails all along the side of the fjord and the sound of wolves from the far side. A frost gave the ground a speckled appearance and outlined some of the stones in white. It all looked quite ghostly. There were ground hugging willows with their orange leaves startling against the grey ground. The red stripes we had seen from Kinfish and the Zodiacs, translated into intense low red bushes.

In one place, a half frozen stream of water flowed gently downhill. For a short time the water reflected light from the other side of the fjord and it looked like a stream of liquid gold flowing over the grey frosted earth and rocks. Among the vegetation there were the hoof marks of Muskox and they can be seen in a couple of my images. Here they feel like an integral part of the landscape not an unwanted intrusion. It was very different from the icebergs and water but totally captivating.

In the afternoon we returned to the shore but the light then was very bright and I found it hard to find compositions. Looking back, I think being in these extraordinary places created a constant pressure to make images because I knew it was highly unlikely that I would ever go back. However that afternoon I enjoyed the (relatively) warm sun, the silence and just “being” in this special place, trying to take it all in and absorb the experience and environment.

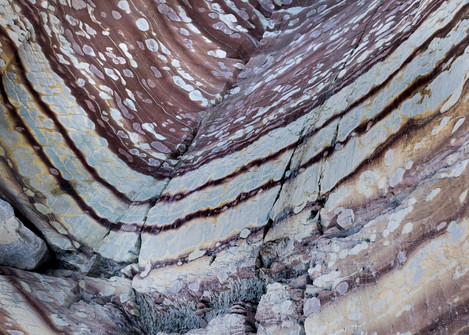

Two days later we went ashore at a place with a totally unpronounceable name so we adopted Beau’s version which was “Seagulls Eat Carpets”. It was one of the few places where it was possible to get “up close and personal” with the “insane” geology of East Greenland. It is an amazing place. All of the stripes, curls and colours of the geology in the mountains were laid before us on the ground. The stripes are Ice Age deposits of limestone and dolomite called tillites and are about 600 to 542 million years old.

We only had a couple of hours there, I could have spent a week. Here I was, back on familiar technical ground with a tripod and I even had a filter or two out of the bag. Aware that we only had a couple of hours before we had to move on, I felt like a kid in a sweet shop and in hindsight, rather rushed in. I wish I had taken a little longer to look around and get more of a feel for the place, as I usually would in a new location..

The colours, patterns and shapes of the rock formations were beautiful and right there, close up, with sea and mountains as a backdrop. Also, the now familiar autumnal vegetation was sparsely but stubbornly growing in this dry, rocky terrain adding yet another dimension to the location. We were there early in the morning and the light was beautiful. There were large areas of red rock with white and pink “tillite” stripes going through it and others where these stripes had crumbled into coloured shards or revealed alternate flat layers of red rock and startlingly white limestone. As with most of our time in Greenland, there was very little wind and the sea in the sheltered fjords was very quiet.

The final place where we were able to go ashore and experience the tundra vegetation was Red Island in Scoresbysund. It is exactly as the name implies, a small island of solid red rock with the added attraction of another iceberg graveyard. Here the vegetation was denser, a bit like heather, but with delicate and complex patterns, colours and textures. We Zodiaced through the icebergs to Red Island, wading ashore through brash ice then on to the top where we spent the afternoon photographing from the ridge which ran along the length of the Island. Although we had not climbed far, the height gave a new perspective of the area. Kinfish looked small in the distance. On one side was a narrow channel between the Island and mainland with icebergs packed into it.

I made some images with the autumnal tundra in the foreground and the cool bergs behind. However the sharp geometric shapes and cool blue colours of these bergs and their shadows above and below water, to me, sit uncomfortably with the softness and warm tones of the tundra foliage. .

On the other side of the Island, the grounded icebergs stretched away into the distance under a magenta grey sky. We were all sad to leave Red Island as this was effectively the end of our time in Greenland, the next day we were heading to Iceland and home.

Back home, eighteen months later and I am still finding images which had been overlooked and my “favourites” collection continues to expand. As well as impressive and beautiful icebergs and polar bears, the collection has many images of the tundra and they are just as evocative of our time on Kinfish. I consider myself extremely lucky to have visited this part of the world and seen this hidden land for myself.

References

1For those who would like to know a little more about the geology I found a very interesting and readable article on the Geology of East Greenland.