George Orwell on Jura

Craig Easton

Craig Easton is an internationally acclaimed photographer whose work explores issues around social policy, identity and culture.

Known for his intimate portraits and expansive landscapes, his pictures are often presented alongside text and audio to weave a narrative between contemporary experience and history.

In 2021 Craig Easton was awarded the prestigious title of ‘Photographer of the Year’ at the SONY World Photography Awards and the following year was recognised with an ‘Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society’. In 2023 he was awarded the ‘Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture’ in the USA and at The Orwell Awards, a special prize for Thatcher’s Children in recognition of his long-term commitment to ‘Exposing Britain’s Social Evils’.

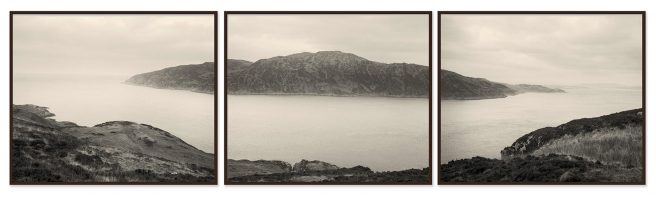

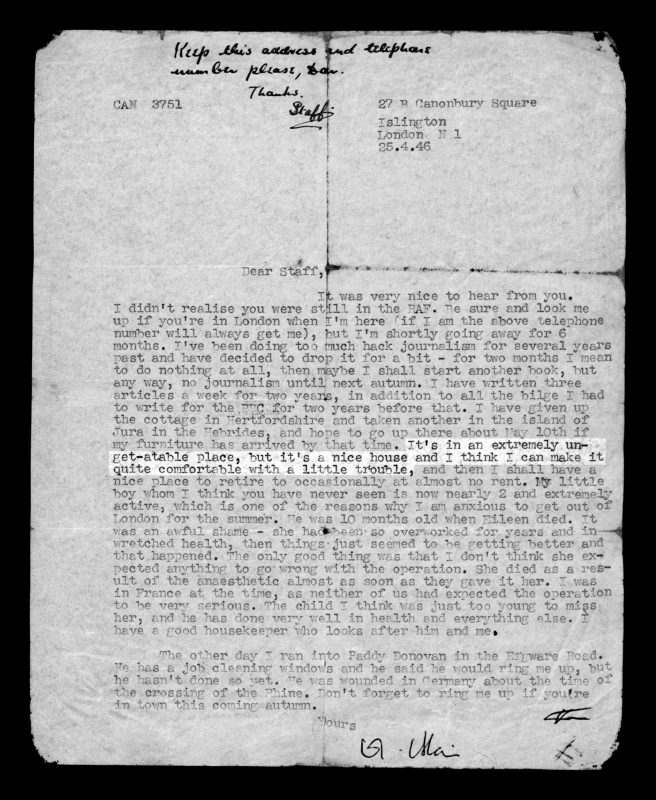

Craig is the author of three critically acclaimed monographs: Fisherwomen, Bank Top and Thatcher’s Children. His forthcoming book An Extremely Un-get-atable Place: George Orwell on Jura will be published in Autumn 2025, the first of three books made in the Scottish Islands that will become a boxed set called An Island Trilogy.

A new book by British photographer Craig Easton is a lyrical reimagining of the time George Orwell lived on the Isle of Jura, where he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. A kickstarter campaign runs until 6th June, offering reduced price signed books and exclusive prints.

Celebrated for his award winning portraits and social documentary, Easton turns his large format camera to the landscape of the Hebrides, but maintains a political undercurrent to his new work.

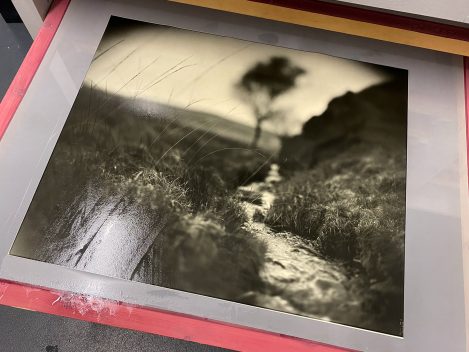

We asked Craig to write about the background to the project, his connection to the Isle of Jura and George Orwell and a bit about his working process shooting 8x10 film and making hand-made silver gelatin prints toned in tea...

A Hebridean dream

Thinking always of my island in The Hebrides, which I suppose I shall never possess nor even see.

So wrote George Orwell in his diary on 20th June 1940. But he did see it… albeit after the unimaginable and cataclysmic events that had happened in the intervening years - on the global level, of course, but also on the most personal level for Orwell himself when he lost his wife, Eileen, to a devastating and untimely early death.

The Isle of Jura had been a dream for both of them… writing to him in March, 1945 after corresponding with the owners, she described Barnhill as "Quite grand - 5 bedrooms, bathroom, W.C., H&C and all, large sitting room, kitchen, various pantries, dairies etc. and a whole village of “buildings” - in fact just what we want to live in twelve months of the year."

Eileen never got to see it, though, and it was a year later that Orwell took up the lease.

A principle reason for the move was to escape the pressures of his journalism commitments in London and to give himself the time and space to focus on what he considered his real work: “My house is in the Hebrides, and I hope to be fairly quiet so that I can start a new novel” he wrote to Yvonne Davet on 8th April, 1946.

And that’s the bit I intuitively understand; the need to escape, the need for time and space to allow yourself to think and be creative.

And so, in a time of political turmoil and confusion, I drew comfort from Orwell’s words and made my way to Jura to read, to walk and to refocus my energies. My two most recent books, Bank Top and Thatcher's Children, were both political in their different ways and I needed time to think, to find joy in the small things in life: the landscape, the weather (yes, even the Scottish weather in February!), the aesthetics of wind-blown trees or chipped teapots. For days and days, I walked and looked and photographed, then spent the night by the fireside imagining Orwell’s life there in the 1940s, reading and sipping some fine Jura whisky that the owners had kindly left out for me.

Orwell, the islands and me

But what was it about Orwell and Barnhill that made me want to make this work?

I know the islands well of course (this is book one of a trilogy). I’ve read a lot of Orwell and have been to Jura umpteen times over many years. And I knew of Barnhill but had never been to the far north end of the island - it's quite a schlep from the end of the public road.

“The only real snag here is transport – everything has to be brought over 8 miles of inconceivable road...”, Orwell wrote to Richard Rees on 5th July 1946.

There are the obvious sociological and political parallels between Orwell's warnings from the 1940s and the concerns that resonate today of course – you can hardly open a paper without reading the word ‘Orwellian’ - and I can’t deny that that was part of why his writing was on my mind, but beyond the dystopia of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four I was also interested in what drew him to Jura.

Finding hope

As well as his novels, I knew of his nature writing and his need for balance – the political and the poetic. I too need that – I often joke that I do love songs as well as protest songs… and so, like my earlier work Fisherwomen, this is perhaps a love song, a homage to Orwell and an acknowledgement of what he once wrote in his essay Some Thoughts on the Common Toad:

Is it wicked to take a pleasure in Spring and other seasonal changes? To put it more precisely, is it politically reprehensible, while we are all groaning, or at any rate ought to be groaning, under the shackles of the capitalist system, to point out that life is frequently more worth living because of a blackbird’s song, a yellow elm tree in October, or some other natural phenomenon which does not cost?”

“I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and – to return to my first instance – toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable, and that by preaching the doctrine that nothing is to be admired except steel and concrete, one merely makes it a little surer that human beings will have no outlet for their surplus energy except in hatred and leader worship.”

With that in mind, then, I took off up to Jura with my old 1952 Deardorff, a box full of 10x8 film and an even bigger box of books. I had been invited to stay at Barnhill – almost untouched since Orwell’s time – and found the place both challenging and restorative, an opportunity to regroup and refocus.

And for me, the work I made there is about hope, a chance to find joy in the small things, to celebrate what’s good in the world. I wanted to challenge the widely held misconception that Orwell went to Jura as a lonely, dying man full of angst to write a tirade against a fearful future, but rather focus on his optimism and hope and his belief in a better world. Despite the horrors of the war, despite losing his wife, and the challenges of severe tuberculosis, he was determined to build a new life for himself and his young son Richard, who, now aged 80, has written the foreword for the book. It was with that sense of optimism that he moved to Jura, to think, to grow vegetables and to find time to write what was essentially a warning to all of us of the horrors that come if we allow authoritarianism to take over.

And in that vein, I too, took solace in the landscape and the quiet of the old house – so still and so quietly evocative of the time that Orwell had sat up in the top room, typing out his great novel.

Printing and toning with tea

Back in the darkroom, the connection and the pure joy of photography continued; after much experimenting, I settled on toning the silver prints with tea – a nod to Orwell’s famous love of the drink and his delightful essay of 1946, ‘A nice cup of tea’.

The book’s title comes from a letter to Stafford Cottman on 23rd April 1946

“I have taken a cottage in the Isle of Jura in the Hebrides… it’s an extremely un-get-atable place, but it’s a nice house and I think I can make it quite comfortable with a little trouble.”

Book Details & Kickstarter

An Extremely Un-get-atable Place will be published by GOST Books as a large format monograph – approx. 14”x11” printed in beautiful tri-tone by EBS in Verona

I am running a Kickstarter campaign to part fund the printing and production costs. If you feel able to support me, I would be very grateful.

Thank you.

Please visit the Kickstarter campaign or www.craigeaston.com