From Platinotype to Chrysotype

Robert Poole

Robert Poole is a “retired” University Professor. His scientific and laboratory background led him away from “yet more computer work” to traditional photography, wet processing and large format cameras. He still prints in silver-gelatin but increasingly in platinum on fine art papers - perhaps the summit of ‘alternative processes’. He is also one of the few to have embraced Mike Ware’s New Chrysotype process for printing in pure gold. He has attended workshops with monochrome masters including John Blakemore, Fay Godwin, Jan Groover, Alan Ross and John Sexton. He has exhibited in the UK, USA, China and Australia and been published in numerous periodicals and books. He won the 2020 Dr Mike Ware Award for alternative photography.

Younger readers of On Landscape and most photography magazines or websites might be forgiven for thinking that contemporary photography equates solely with digital cameras, computer image processing and inkjet printing. However, silver-based film and traditional darkroom printing are making a healthy comeback in art colleges and among amateurs. Whether silver-gelatin is really ‘alternative’ photography is a moot point.

It’s certainly an alternative to an inkjet printer. My personal definition of ‘alternative’ excludes silver-gelatin film photography but embraces instead a vast collection of lesser-known methods. Contemporary photographic print-makers have a bewildering range of print media with which to show their work, whether in landscape or any subject matter. This is not the place to list them all, but see https://www.alternativephotography.com. Other valuable overviews are Christopher James’ The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes, Third Edition (2016, Gengage Learning) or Lyle Rexter’s Photography’s Avant-Garde (2002, (Harry Abrams Inc., New York). The former book is a great one-stop shop if one wishes to learn the methods.

Among the better-known ‘alternative’ methods are albumen, argentotype, calotype, gum bichromate, kallitype, salted paper and Van Dyke processes. The list of processes is so long that only a few are going to be celebrated here, focusing only on the iron-based processes or siderotypes. Among all these ‘types’, siderotypes are easily defined: these are processes that depend on the light sensitivity of an iron-compound (from Greek sidēros "iron"). Note that all these processes are contact processes: the printed image will be the same size as the negative. Any large-format photographer using film can easily generate these, but it is more common now for practitioners to make, from small-format film or digital images, the required large ‘digital negatives’ (a misnomer, since obviously the negative is not digital, but rather the process used to get there is).

Cyanotype

Let us look at just three families of siderotype: cyanotypes, platinotypes and chrysotypes. Cyanotypes are by far the most commonly practised. Cyanotype papers are widely available and cheap. Amazon will sell you a pack of dozens of ready-prepared papers for less than £10, requiring only a negative or flat object, such as a leaf, as your subject, and UV light, such as the sun. These papers are already coated with a sensitising solution (which is NOT an emulsion, despite numerous references to such in the popular literature and online).

The first book to be printed and illustrated entirely by photography was Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, an exceedingly rare and privately published book of 1843. The images can be seen in Sun Gardens – Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins (2018) by Larry Schaaf (The New York Public Library). Cyanotype is certainly useful as an inexpensive, easy introduction to hand-coated papers and alternative printing. Those who find the strident blue colour (due to the pigment Prussian Blue in all pure cyanotypes) unsuitable for their subject matter (such as landscape) can tone the print in a host of unlikely ‘chemicals’ such as tea. A greatly improved version, the New Cyanotype, was introduced by Dr Mike Ware and is finding wide acceptance.

Plantinotype (Platinum-Palladium)

From the ridiculously simple and inexpensive to the sublime: let’s look at Platinotype or, more correctly in most applications, platinum-palladium printing. Note that Pt and Pd are the only chemically correct abbreviations for these elements. Unlike cyanotype, one cannot buy ready-to-use papers, that is, papers that have already been coated with the light-sensitive chemistry. However, such papers were once available, testament to the popularity of the process: William Willis’ patent of the Platinotype in 1878 accompanied the sale of pre-sensitised paper and processing solutions. Platinum became the method of choice for luminaries such as Frederick Evans, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand and others. But by the early twentieth century, platinum had been elevated to the role of an essential catalyst for manufacturing nitric acid, itself used in the manufacture of explosives for the Great War. In 1917, palladium (a metal closely related to platinum) was introduced and quickly adopted.

The commercial values of platinum, palladium and gold fluctuate widely, but palladium was once the cheapest, only to become the most expensive later; now, gold again is the most valuable. These fluctuations are reflected in the prices photographers must pay for their supplies. All commercial production of pre-sensitised platinum-palladium printing papers had ceased by the 1930s, and the 1930s to 1980s was a period of dormancy in printing with these metals. Now there has been an extraordinary and exciting re-emergence of handmade photographs, ‘hand-in-hand’ with other tactile pleasures (think vinyl records and cars with a manual gearbox!).

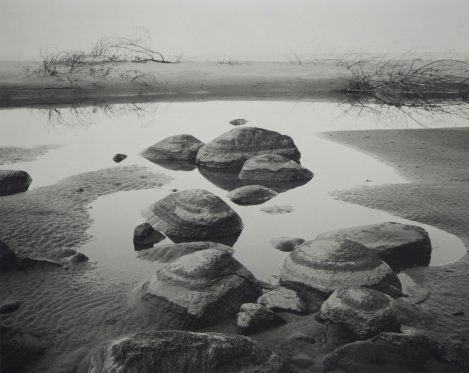

Printing in platinum and palladium is perhaps the summit of ‘alternative processes’. Revered for permanence and subtle beauty and composed of platinum and/or palladium metal embedded in the uppermost fibres of the print’s paper, these photographs are characterised by luminosity, longevity and an extraordinary tonal range. The appeal of this process is timeless and is endearingly described by Malde & Ware in Platinotype (Malde & Ware, 2021, Focal Press): “precious metals precipitated so finely that higlights slide to the edge of the paper’s base white.

The traditional method of making platinum-palladium prints (the ‘development method’) is still very widely used and requires two stages: the platinotype sensitiser (a solution of platinum and/or palladium salts) is mixed with ferric oxalate and used to coat (by brush or glass coating rod) a sheet of fine, generally 100% cotton, paper. (Here is not the place to describe how this is done, but it is not difficult to master). After drying, the paper is pressed into contact in a printing frame with the large negative and exposed to ultraviolet light. The iron is reduced to the ferrous form (by accepting an electron). At this point, no further chemical reaction can occur in the dry state. The paper is then transferred to an aqueous developer, which provides conditions for dissolving the ferrous oxalate, whereupon it reduces the platinum and/or palladium salts to the precious metal element(s), Pt and Pd, which are deposited within the cellulose fibres of the paper. This development is dramatic: an image appears almost simultaneously, and many videos online like to show this (for example, https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/video/conservation.html).

My own platinum-palladium photographs are made using the newer Malde-Ware process that provides a 'print-out' image. Dr Mike Ware has made available a comprehensive background to his formulations for the platinum-palladium process as well as Chrysotype (see below), New Cyanotype (see above) and argyrotype ( a silver process related to the historic Van Dyke process. See https://www.mikeware.co.uk/mikeware/downloads.html. The rigorous physicochemical basis of these printout methods and the ability to judge the progress of the printing during UV exposure ensure economy of materials and optimal print control without using suspect additives. This is of enormous practical benefit. For example, since once the image in a platinum-palladium print is fully visible on development in the traditional method, it's too late to adjust the exposure time! This method is also exhaustively and admirably covered in Platinotype (Malde & Ware, 2021, Focal Press) and included here (https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/video/conservation.html). The chemistry uses different compounds, but the key point is that the paper is allowed to acquire a controlled degree of humidity, which will allow the reactants to form the image during exposure. After exposure, three successive baths remove the unreacted chemicals.

Chrysotype

The gold process was discounted long ago as a viable printing method and forgotten for eighty years until Mike Ware, armed with his professional background in chemistry, revisited the process and introduced a wonderful printing-out process in pure gold (chemical symbol Au). He named it the ‘new chrysotype’ (from the Greek chrysos) in honour of Herschel’s invention of 1842. Surprisingly, relatively few have embraced it, but those that have value its remarkable ability to endow the print with subtle split tones and hues in blues and pinks, or neutral hues approaching those achieved in the platinum-palladium processes.

Obviously, the chemistry is different. The gold salt (tetrachloroaurate(III) is bound to a stabilising sulfur ligand (3,3'-thiodipropanoic acid); the sensitising solution also contains, as for platinotype, a UV-sensitive iron compound, ammonium iron(III) oxalate. Again, the iron compound is reduced by UV exposure (ferric to ferrous), the latter then reducing the gold to elemental gold, Au(I), which is deposited in the print to form the image. After exposure, the paper with a clearly visible image is immersed in a series of baths, the first of which can radically determine the colour(s) in the final print. For full details, see https://www.mikeware.co.uk/downloads/Chrysonomicon_II_Practice.pdf.

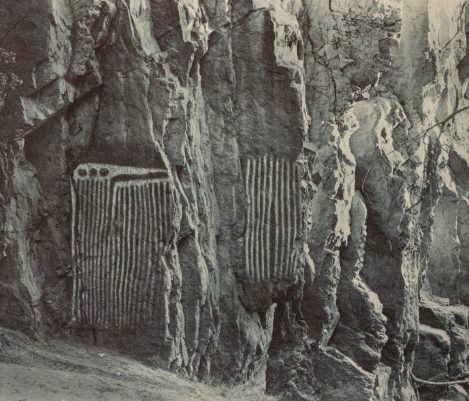

One of its striking characteristics is that the final colours in the print are not “golden yellow” but dependent on a large number of variables, including the humidity of the coated paper prior to UV exposure, subsequent post-exposure hydration, the developing agent and the properties of the paper. Paper choice can have a major influence on the colour of a chrysotype: gelatin-sized papers favour the formation of reddish images. The gold in the image comprises dispersed nanoparticles. When light falls on these particles, rather than being reflected, it is scattered and absorbed at particular wavelengths, depending on the size of the particles, which is in turn dependent on the processing of the print. Hence, the eye perceives different colours.

Repeating a colour achieved in one print can be challenging, satisfying or infuriating, depending on your outlook. Chrysotypes are rarely seen but deserve to be. Like platinum-palladium prints, chrysotypes are archival and permanent, gold being the least chemically reactive of all metals. Its use in jewellery or bullion is testament to this.

Any technical difficulties and requirements are not insurmountable. A strong UV source is more easily accessible now because of the ready availability of LEDs that emit in the UV range, and contact printing frames and fine art papers are common enough. The main stumbling block for photographers who cannot access the chemicals off-the-shelf from scientific vendors (that is, almost everybody in the UK, because of burdensome Health and Safety regulations, but not in the USA), is the chemistry. However, premixed sensitisers, especially for platinum-palladium, are available from a small number of sellers. My own protocol is to make up all the required solutions from ‘raw’, dry powders. I use an intense UV light source comprising a dense bank of LEDs emitting the optimal wavelength (365 nm) from Cone Editions, Vermont, USA and contact-printing frames from Lotus View Cameras, Austria.

Exposure times are a minute or more. My current papers are Arches Platine, Legion Revere Platinum, Ruscombe Mill’s Buxton, Talbot and Herschel papers and occasionally fine Japanese papers. For all these processes (cyanotype, platinotype, and chrysotype), I mask with Rubylith (or tape) the edges of the negative so that unexposed sensitiser does not leave an untidy margin around the final image. I find the traditional, rectangular frame unpretentious, which does not detract from the image content. I don’t think it’s necessary to ‘show the brush marks’ or extent of the coating in order to prove that it’s a handmade print. Connoisseurs will already know that. There is also a critical technical reason: the masked margin that has been coated with sensitiser, but is unexposed, provides the best visual test of the complete clearing of excess chemicals from the print during the wet processing. If those areas are unmasked, exposed, and darkened, one can never tell if the print has been properly cleared.

Conclusions

These alternative printing methods have much to offer the landscape photographer, as illustrated in the images on https://www.alternativephotography.com. Examples of my own work in platinum-palladium and chrysotypes are shown here. A final remark: these methods rarely produce prints that are perceived as ‘sharp’ as silver-gelatin or computer-generated prints: the surface is absolutely matte, and the texture of some art paper bases can obscure the finest detail. But they are beautiful! Look at original platinum prints, not reproductions; like me, perhaps you’ll be blown away.