A final contribution

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

The idea that an artistic expression of harmony was an allegory for reinforcing the dominant social foundations is still a compelling argument. Landscape art has long been associated with power and order…. However, at this moment of environmental crisis, creating lyrically evocative narratives that connect us to our landscape is an act of resistance. This way of perceiving the natural world has also become a personal way of building a playful relationship with the landscape that addresses memory, nostalgia, history, landscape, place, storytelling and the passing of time ~Simon Dent, in Shan Shui in Silva Emete1

With film photography we photograph what we saw; with digital photography we see what we have captured without really having looked, nor really been able or even wanted to composev~André Rouille, Le Photo-Numérique: Une Force Néo-Liberale, 2020, p.47

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot ~Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi, 1970

As I write this, I am rapidly approaching 75 years old and thinking that is probably a good point at which to stop producing articles for On Landscape before some elements of old fogeyism start to creep in (and, be warned, this may already be evident in what follows)2. So, this article will be my 30th and last contribution and consequently provides an opportunity for reflection. When I wrote my very first article (some 8 years ago now) on The Science and Art of Hydrology3, it was an initial attempt to try to convey (and help to understand myself) what lay behind the types of landscape images that I was producing, particularly, as an academic hydrologist, those of water. This “trying to understand” has been a recurrent theme in articles since, including exploring some of the debates on photographic philosophies.

Because it has been suggested elsewhere that the technological advances in the last 200 years have far outstripped the capacity for human evolutionary adaptation and that this has resulted in a modernist separation of people from nature, both in the developed world and increasingly elsewhere. At its most basic, the technological developments that have provided shelter and comfort (for most), access to travel (for many), and fast communications and information/disinformation (for nearly all, in the West at least) have also served to create barriers between people and the landscape5. Those developments have meant that we are now living unsustainably on this earth and, in the majority, do not care enough about the exploitation of resources and resulting changing climate (present readers excepted, of course). Or rather that some of us might care, but are not willing enough to make sufficient major changes to our lifestyle to make it more sustainable – and that can often include our photographic practice.

This is, of course, despite the evidence that being out in “nature” is good for us both physically and mentally6. That benefit will depend on the nature and landscapes that are accessible to us, but even urban green spaces have been shown to have important positive impacts (while the negative impacts of exclusion from nature, such as during the Covid lockdowns, are also well recorded). In Switzerland, where I spend much of my time now, nature is readily accessible through good public transport systems and a network of well-marked trails for walking. But even in the Swiss landscape, the negative impacts of technological advances are all too evident when walking past the infrastructure associated with the ski industry, the surface damage resulting from ski runs and access roads, ways of storing water for use in snow canons, valleys drowned by dams for hydroelectric power generation (providing renewable energy of course) and fields disappearing under construction sites. Observing the increasingly rapid retreat of glaciers, accelerated by climate warming, is particularly sad7. That does provide opportunities for some images of waterfalls sustained by glacial melt throughout the summer, but many smaller glaciers will soon be lost completely so even that will not last in the longer term.

On the other hand, technological advances have meant that we have more scientific understanding of nature and landscape. Meteorological, hydrological, geological, pedological and ecological knowledge has been driven by, and also required by, advances in technology in an analogous way that we, as photographers, have driven and served (by buying new gear) the developments in camera technology, as Vilém Flusser pointed out more than 40 years ago. That scientific knowledge means that we could have a more harmonious and sustainable existence on this earth if there were not so many barriers to evolving to doing so.

Traditional pre-technological societies did not have such barriers. They were much more intimately embedded in the landscape, even if more vulnerable to natural disasters. Such societies had to know their landscapes intimately to survive.

But how does this relate to what we do as photographers?

It is evident that there has been dramatic progress in digital sensors over a short period of time, a good breeding ground for GAS and upgrading of kit, even if we do not really need the latest resolution and generation. The result, especially as a result of advances in mobile phones, has been a plethora of images, with resolutions that are way beyond what is necessary for anything that most of us will display electronically or print in hard copy form. It is currently estimated that some 61400 images are taken every second and that nearly two trillion will have been generated in 20249. Storing these images, both locally or in the cloud, requires resources of both hardware and energy that is adding to climate change. Sharing those images across the internet, requires more hardware and energy, that is adding more to climate change. The numbers continue to grow, despite our awareness of climate change and its potential impacts (and there are, of course, many other ways in which we as photographers contribute to CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions10).

It can also be argued that part of the problem is that the camera itself puts another hardware barrier between us and the landscape. Looking through the viewfinder, we do not see a living landscape, we see a potential composition. We “take” images from the landscape in a way that is conceptually a form of exploiting the natural resource. Normally, that might have only a minimal impact (depending on how far we have had to travel to be there) but there are also some particularly vulnerable sites made popular though Instagram and YouTube where selfish or careless photographers - or just the sheer numbers of photographers - are damaging the site to get the shot or even just to take a selfie with the landscape as background11. Our adaptation to the technology is greater than our adaptation to the threats to the landscape and to life within it. In part that is because we are rewarded by our use of the technology - in having a record of our lives, or images that we can share with others, exhibit or put in a book.

With digital this has become even easier, because we can immediately review the images we take. We are encouraged by the technology to make ever more use of the technology. The numbers of images continue to grow and grow, encouraged by the apparent low cost of digital images, but with the all-but-hidden cost of using more and more resources (and the impact of AI generated images is only just starting to be felt)12. So now, on the one side we are overwhelmed by images of landscape beauty, and on the other we are overwhelmed by images of landscape loss and destruction (and the impacts of war and famine). We allow both to coexist, discordantly, in our minds and, sometimes, our practice spans both.

It is recognised that human evolution and adaptation is shaped by culture and technology much more rapidly than can occur by genetic changes.

Culture provides a second, and extraordinarily powerful, way of evolving. Genes encode information about phenotypic solutions to problems that organisms encountered in the past, and that information is transmitted only from parents to offspring. By contrast, cultural information—knowledge, technology, ideas and preferences—can be disseminated broadly, and the information can accumulate within a single generation ~Richard Lenski, 201613

Indeed, it has been argued that humans have put limits on the process of natural selection by having the technology to ensure that nearly all children survive to adulthood.

There's been no biological change in humans in 40,000 or 50,000 years. Every thing we call culture and civilization we've built with the same body and brain ~Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), 200014

So what needs to evolve culturally to deal with this technological overload and failure of sustainability?

Is it possible to bring some harmony to this cacophonous cascade of discords? Harmony has long been taught as one of the fundamental principles of art (the others commonly cited being balance, emphasis, movement, proportion, rhythm, unity and variety). Harmony in this sense means having a good balance of elements of colour, value, shape and textures in an image to produce an effect of wholeness. There are many articles online about harmony in photography, for example on how to use the colour wheel and complementary colours in composing an image (or, less happily, in how to modify colours in post-processing for greater harmony and impact)15. But harmony (as well as its musical connotations) also has the wider definition of living peacefully with one another, or of living in harmony with nature.

It is naïve, of course, to suggest that pre-technological societies lived in harmony with nature. They also exploited nature for survival (and in some parts of the world still do) and were affected by natural disasters of floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

In fact, we are not short of philosophical advice about achieving harmony, from Confucianism and Taoism in ancient China; the Vedic philosophy of ancient India; Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics in ancient Greece; Marcus Aurelius in ancient Rome; to Leibniz, Schiller, Santayana and Naess in more modern times17. There was even a 2010 report by the Director of the United Nations that linked the goals of sustainable development to living in harmony with nature18.

Dwell on thoughts that are in harmony with nature and her laws, and act accordingly. Don’t let yourself be pulled off course by the insults or injuries of others. Let them go their way and you go yours, continuing on the path of reason. This is not selfish or antisocial on your part—far from it. Your individual reason is not opposed to the common good, but in harmony with it.” ~Marcus Aurelius, 121-180 BCE

While human evolution has changed little with the advent of industrial technology, clearly societal evolution and the nature of thought have changed dramatically in the last two centuries since the Enlightenment and its myth of understanding and controlling nature that drove the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. While we still create myths of sustainability today, underpinned by idealism as well as science19, modern society is largely based on exploitation of both nature and people. The ideals and myths of living in harmony with nature have been largely lost. If we think about images in this way, then those that reveal the beauty of landscape might be considered as attempts at harmony; while those that represent loss and destruction are recording the ways we are failing to live in harmony with nature. Making and presenting either type of image can be considered as a political act (even if we rarely think about it in such terms), but the cases where the such images have had real political impact appear to be few.

Those few celebrated cases do, however, include the role of the images of Carleton Watkins in the designation of the Yosemite Valley as the first National Park in the US in 1864; the images of Ansel Adams (1902-1984) in the formation of the Kings Canyon National Park by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940; the images of Horace Kephert (1862-1931) and George Masa (1885-1933) that influenced the designation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 193419; the Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend image of Peter Dombrovskis (1945-1996) in saving the Franklin River in Tasmania from hydroelectric power development in the 1980s21; and the Colorado photographer John Fielder (1950-2023) whose work inspired the Colorado Wilderness act that created 36 wilderness areas in the state22. But the images of Eliot Porter in The Place No One Knew23were too late to save the wonders of Glen Canyon from inundation under Lake Powell (though recent long term droughts, thought to be exacerbated by climate change, have allowed some of the side canyons to be visited again).

While Walter Niedermayr’s striking images of the Alps, including skiers and ski infrastructure, are also political in this sense of raising awareness, they have not resulted in any constraints on development. Martin Parr’s Small World images have not had led to any mitigation of the overtourism that is producing demonstrations and active resistance in places such as Barcelona, Venice, Mallorca, Bali, Santorini, and even rural Galicia24. Some of the aerial images of the destruction caused by mining and tailings by Edward Burtynsky even give the impression of abstract beauty, and certainly have not had any impact on the sustainability of mining practices25.

All the images of retreating glaciers, both by photographer artists, scientists and satellites have had little impact on national policies, even in Switzerland and other countries being significantly affected (some 10% of glacier volume in Switzerland has been lost in the last 2 years26). All the artistic images of lakes and rivers in Britain have failed to stop the illegal releases of untreated sewage that is having such an impact on the water quality and ecology. Even images of the sewage releases or resulting eutrophic algal blooms and all the scientific data that has been collected, including by citizen scientists, and public demonstrations have not yet had any significant impact on the practices of the water industry or policy in government27 (but we should hope that will not last). All the wonderful images of the amazingly skilled and dedicated wildlife photographers have done little to halt the decline in numbers of birds and animals as we live out the 6th mass extinction28.

Indeed, it can seem that images reflecting the beauty of nature only serve to suggest that the degradation is not so serious. Perhaps the very fact that image numbers continue to grow and grow only serves to minimise such political impacts. The sheer numbers have only meant that images will be less effective than 80 or 100 years ago. Already as individual landscape photographers, we tend to have an overload problem with the images we take ourselves, since although we will not consider them all to be of the highest quality it is still difficult to delete all the others since our opinions might well change in a few months or years (…though again that storage really does have a real cost in resources and energy, even if our travel to get to the places we photograph might dominate any other photography related energy consumption or CO2 emissions). That is not to say, however, that the hope for political impact, has died out. Richard Sharum, talking about his recent book Spina Americana, stated:

It reflects my general philosophy towards photography as an anvil for activism, as well as my opening argument for a new direction in the hope for a more collective and persistent empathy.29

I suspect that most readers of On Landscape will lean towards harmony with nature in ways that reflect our own emotional responses. Many will be prepared to argue that in attempting to show how beautiful nature can be, we strengthen the case that is worth preserving. That has certainly been the foundation for much of my own work. As such, although we do “take” our images from nature, we also want them to be a fairly faithful realisation of the real scene. We would like to hope that the image has some harmony with the viewed reality, our felt experience of being there, and what that reality might mean to us in a time of change.

This was precisely the goal, or mission, of film photographers: to fix a centre to the chaos of the world, to subject it to a geometric order and extract a truth by eliminating, cutting out, purifying until we end up with an intentionally constructed shot, captured at a “decisive moment” … At the opposite end of the spectrum are digital photos: too quickly taken, too fleeting, often too banal; they undermine the viewer's desire for the aesthetic experience of contemplation … The quest for truth has been transformed into a consumption of fictions ~André Rouille, Le Photo-Numérique: Une Force Néo-Liberale, 2020, p98/89/98

Many landscape photographers have written about the value (be that physical, psychological or spiritual) of being out and about in the landscape, over and above any images that we might bring back from any of our excursions. It does not even need any camera to be involved, which brings me back to my favourite photographic quotation, much cited in On Landscape30 and elsewhere, of Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) in the Los Angeles Times of 13th August 1978, that “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” The advantage of going for a walk with a camera is that it really concentrates the mind on looking, in particular in seeing some of the detail of what is there (and perhaps then create a composition)31.

And, returning to Vilém Flusser, there is always the challenge of avoiding redundant images. It is ever more the case that everything has been done before, that every new image is in some sense redundant, another version of the same. It might be our own version of what has been done before, with a degree of personal satisfaction of capturing the shot, but might there not be more interesting ways of trying to avoid redundancy? One way that might be more harmonious could be to explore the locally unique surroundings in preference to those highly photographed places that require long distance travel and that have been seen so often before. There might then be more satisfaction in the hunt to find something more original, more personal, than going somewhere far away to only produce redundant images you will already have seen. As David Ward put it:

It's important to me that I am making an enquiry about my surroundings in my images, rather than imposing a conclusion. I am not seeking to make definitive statements because I don't know the answers. The questions vary enormously from image to image; I might be asking about the colour of light or what is it that is beautiful about moving water or why I find that arrangement of elements interesting or musing on the ecology of a particular place.” ~David Ward in Nobody Expects the Inquisition32

This implies that we need to evolve a deeper, more thoughtful, approach to the landscape. Many landscape photographers are there already, of course, including the readership of On Landscape and those photographers following the 7 Nature First principles33 to minimise impact and to leave no trace of our passing in making our images (and ideally in the manner of our getting there too). As with the Swiss glaciers, seeking harmony has to represent more than recording their current beauty in the process of disappearing34. It should involve a consideration of what might be required to preserve that beauty in the long term, to ensure that that our relationship with the landscape might be sustainable in this technologically dominated world. But is then the viewfinder a barrier to thinking in that way and acting according? I think it can be. I think it has been in my photographic life in the past which has not always been so thoughtful about the impacts we have, even though as far back as I can remember I have cared about the landscape35. We have to think, therefore, outside the box, whether it is in hand or sitting on the tripod! To achieve some degree of harmony, both as one of the fundamental principles of art, and in the sense of our reflecting our own authentic feelings about a place or element of the landscape.

So in this, my last, article for On Landscape can I encourage all who might read this piece to evolve your thinking and practice towards a more ancient idea of harmony with nature, and consequently to be more thoughtful about your approach to the landscape and the sustainability of its beauty. That does require a philosophical stance, perhaps the personal philosophy of harmony as advocated by Arne Næss. What might that look like? It means thinking about harmony in the sense of sustainability in the long term, with the classic dilemma that sustainability implies policies at national and global scale and what we can do as individuals seems so miniscule. But if we do care, we should do what we can to live more sustainably; to think about our impacts on the landscape; to reflect nature (and not some artificial or augmented reality); and to reveal the wondrous details of nature that might otherwise be missed so as to encourage the recognition of their value.

You will, of course, appreciate that it really does not seem to be the way the world is going. There are more and more images that are simulacra or constructed reality rather than simulationsin the sense of Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007)36. But in terms of social evolution, education is important. Teach your children well, as the Graham Nash song says37. Do we need to do more to educate our children about nature and landscape before it becomes something that most will only experience as virtual realities in games, as nature documentaries on screens (however wonderful), or as distant backgrounds in selfies38? It is not as if we have not been aware of such change for a long time. If Vilém Flusser has not been widely read, even by photographers, in more popular culture Joni Mitchell was singing, as long ago as 1970:

“They took all the trees and put 'em in a tree museum

And they charged the people a dollar and a half to see them

…

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you got 'til it's gone?” 39

Current technologies create barriers to real experience in favour of experience filtered by the technology. The response to the technology in this case is currently evolving to put the self before the landscape. The rise of the selfie represents a form of disengagement with nature, encouraged by the technology in a way that is not sustainable, but it is also not a necessary consequence. We can evolve our practice to stay aware of what is needed for sustainability and of harmony with the landscape. To cite Brad Carr:

The camera is a vehicle that can carry us towards a place of deep healing, resulting in self-acceptance, and, therefore, acceptance of others. Nature, I believe, is the portal through which we now need to travel if we wish to reverse the damage of the past and co-create a more peaceful, harmonious and loving world to exist in tomorrow.40”

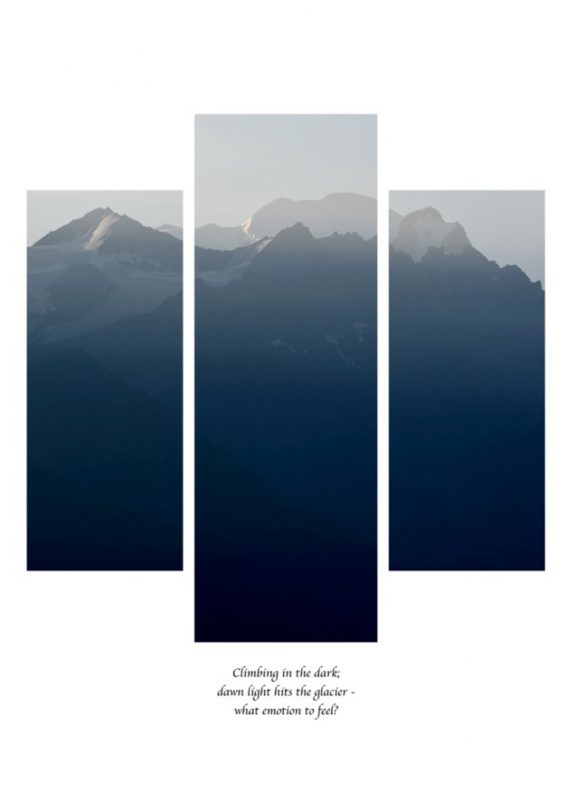

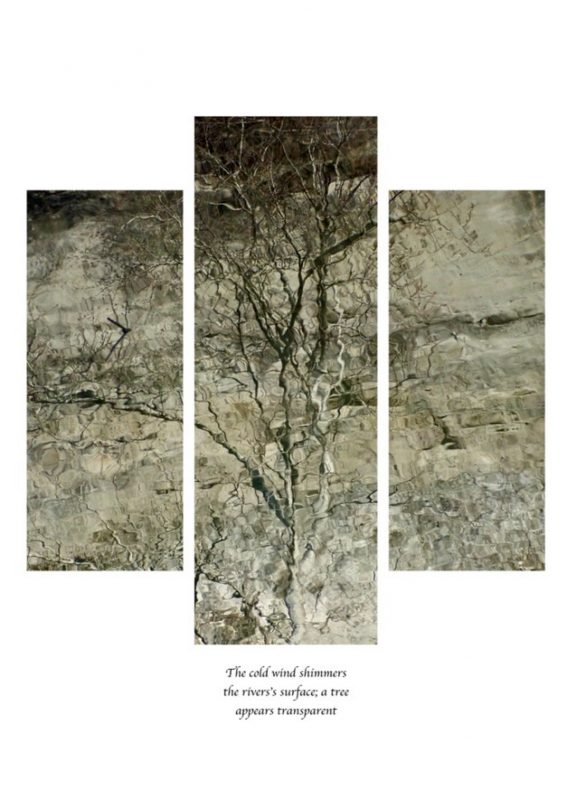

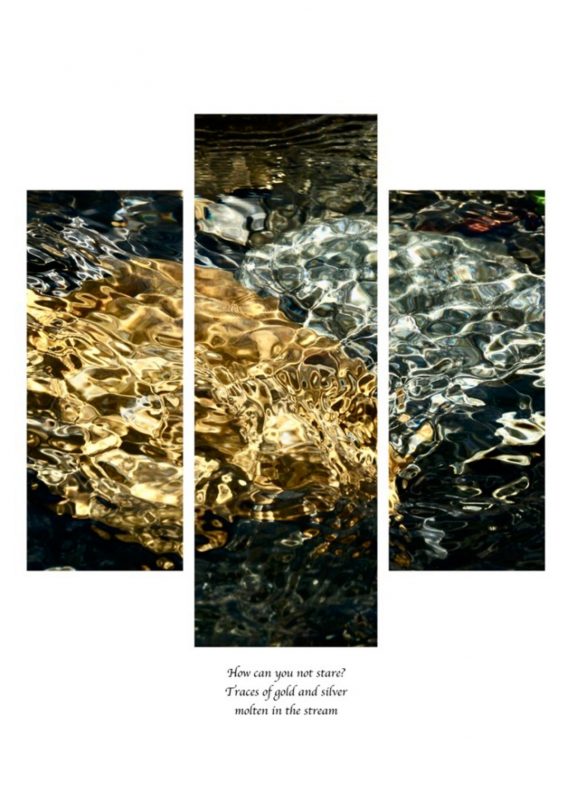

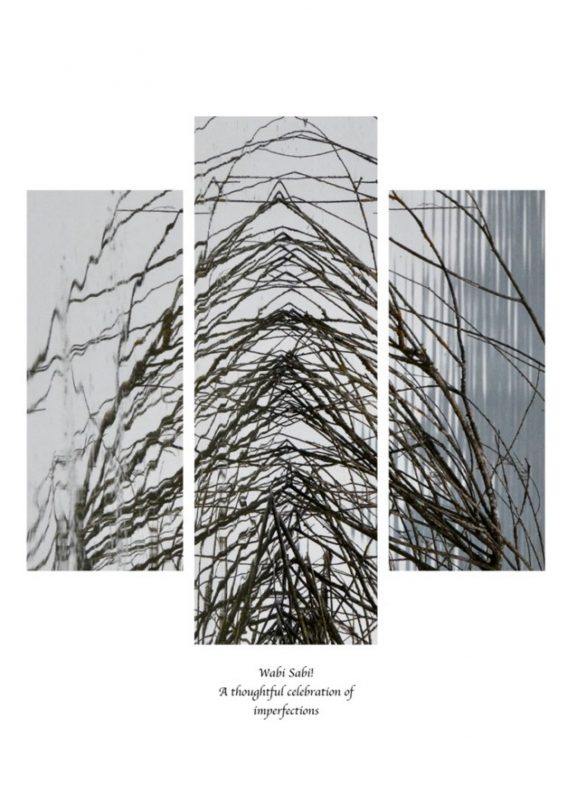

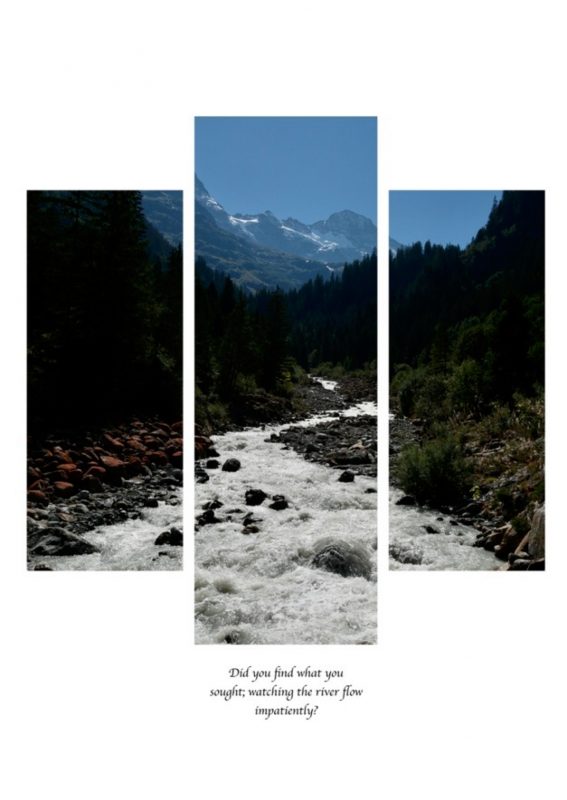

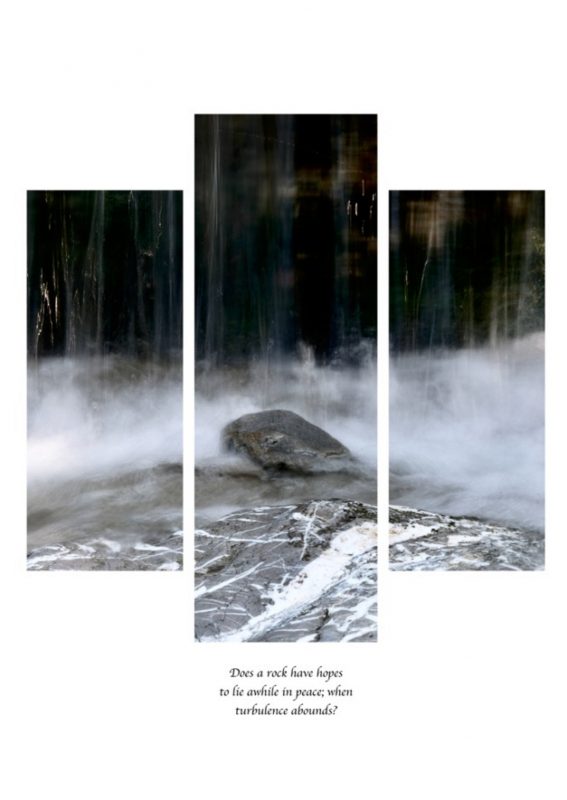

That then is my two-penn’orth. I will stop now and leave you just with a few final images of some new visual haiku, taken from a second volume The River as Haiku41. These have been taken with harmony in mind, mostly on walking trips from our front door or reached by public transport. I hope you will be able to find projects of your own that allow you to do the same.

References

- https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2023/10/shan-shui-in-silva-elmete

- An old fogey may derive from the Scots foggie, fogie (noun) from foggie (“covered with moss or lichen; mossy”, adj) to suggest a dull person (especially an older man) who is behind the times, holding antiquated, over-conservative views. The OED's earliest evidence for old fogey is from 1785, in a dictionary by Francis Grose, antiquary.

- In Issue 135, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/04/the-science-and-art-of-hydrology/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2020/06/landscape-and-the-philosophers-of-photography/

- The writings of the iconoclast philosopher Ivan Illich (1926-2002), active in the 1960s and 70s, are worth exploring in this respect. It was he who, in his book Tools for Conviviality, suggested that the ideal form of transport was the bicycle as a compromise between going further and spending more time travelling. Anything faster and it would necessarily result in more time spent travelling. The proof of this is all the wasted hours spent in airports by many people since. His books on Deschooling Society and Medical Nemesis are also worth reading.

- See, for example, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/sep/04/better-than-medication-prescribing-nature-works-project-shows

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/05/loss-in-the-landscape/ in Issue 231

- See, for example, Cost–benefit analysis of flood-zoning policies: A review of current practice at

https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wat2.1387 (open access). In Switzerland, the risks are also getting greater as seen recently in the failure of the Birch glacier and consequent rock avalanche that buried most of the village of Blatten. This type of risk is increasing as a result of the loss of permafrost in the mountain soils. - See https://photutorial.com/photos-statistics/. Note that Vilém Flusser already talked about the redundancy of most images well before the age of digital photography. A more recent discussion along similar lines is the book by André Rouille, La Photo Numerique – Une Force Néo-Libérale, L’Echappé: Paris, 2020 (in French). The arguments on the service of the digital image to capitalism are not always convincing but the discussion is interesting. André Rouille has published a number of books on photography and maintains the site www.paris-art.com. The only book of his I could find that has been translated into English was A History of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives with Jean-Claude Lemagny from 1987.

- See the article by Joe Cornish in Issue no. 180 https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/03/a-question-of-responsibility/ and the discussions that followed.

- See the article by Matt Payne on concealing locations, especially sensitive locations, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2024/12/geotagging-gatekeeping-location-sharing/.

- An academic paper on Life Cycle Analysis of film and digital imaging from 2006 suggested that:

When all impacts were considered, no single imaging scenario was clearly "better" or "worse" than the others. Imaging scenarios that were advantaged in one impact category were often disadvantaged in others. This leads one to believe that a more complete picture (with more impact categories) would also not show an “absolute winner.” See https://www.mech.kuleuven.be/lce2006/070.pdf. However, their figures suggested that the lifetime number of images for a film camera at that time was only 4800, and actually more than a digital camera at 4500. The number of digital images produced per year since 2006 has expanded exponentially. - http://assets.press.princeton.edu/chapters/s10711.pdf in Jonathan B. Losos and Richard E. Lenski (Eds), 2016, How Evolution Shapes our Lives, Princeton University Press, Chapter 1

- Gould, S.J. 2000, The spice of life. Leader to Leader. 15:14–19., see also Templeton, AR., 2010, Has human evolution stopped? Rambam Maimonides Med J. 1(1):e0006.

- E.g. https://iso.500px.com/color-theory-photographers-introduction-color-wheel/

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arne_Næss. Næss actually called his own ecological philosophy Ecosophy T where the T referred to Tvergastein, the mountain hut where he wrote most of his books. He encouraged people to develop their own personal philosophy.

“By an ecosophy I mean a philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium. A philosophy as a kind of sofia (or) wisdom, is openly normative, it contains both norms, rules, postulates, value priority announcements and hypotheses concerning the state of affairs in our universe. Wisdom is policy wisdom, prescription, not only scientific description and prediction. The details of an ecosophy will show many variations due to significant differences concerning not only the 'facts' of pollution, resources, population, etc. but also value priorities.”

Arne Næss, in Drengson, A. and Y. Inoue, eds. (1995) The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Publishers.p.8 - Even our current King has been involved in a book titled Harmony: A new way of looking at the world, co-written with Tony Juniper and Ian Skelly in 2010 - https://kings-foundation.org/about-us/philosophy-of-harmony/

- https://www.garn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Harmony-with-Nature-United-Nations-Report.pdf. This followed General Assembly resolution 64/196 with the title Harmony with Nature

- See for example the 2024 book Agrophilosophie: réconcilier nature et liberté of the French author and philosopher Gaspard Koenig, who proposes a system based on principles of recycling and individual responsibility for a sustainable soil, scaled up to local self-governing communities and to federal nation states with limited powers. He is not so convincing on how to persuade societies to move towards such a sustainable option unless some “miraculous political circumstances” appear somehow. See https://editions-observatoire.com/livre/Agrophilosophie/544

- See, for example, https://smokieslife.org/product/george-masa/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/06/morning-mist-rock-island-peter-dombrovskis/

- See https://petapixel.com/2023/08/14/revered-landscape-photographer-john-fielder-dies-after-cancer-battle/

- Eliot Porter, 1963, The Place No One Knew, 25th Anniversary Edition published by Peregrine Books in 1988 (ISBN 978-0-87905-249-2) and reprinted in 2000. Michael Engelhard, in his 2024 book No Walk in the Park, points out that Eliot Porter’s book should really have been called The Place Not Many White Men Knew, since there were many places in Glen Canyon that were sacred to the indigenous peoples. The history of the Glen Canyon Dam controversy is summarised in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glen_Canyon_Dam.

- As reported in https://www.euronews.com/travel/2024/09/02/paradise-ruined-why-spanish-locals-fed-up-with-overtourism-are-blocking-zebra-crossing

- https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs

- See https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/28/swiss-glaciers-lose-tenth-volume-in-two-years-climate-crisis#:~:text=Swiss%20glaciers%20have%20lost%2010,have%20caused%20the%20accelerating%20melts. Interestingly, just about the only landscape photographs shown at the recent biennial Images Vevey exhibitions in Switzerland were two of the Aletsch Glacier by Andreas Gursky, the first made in 1993, the second in 2023 (see https://www.images.ch/archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/09/CP_GURSKY_IMAGES-VEVEY_04092024.pdf in French).

- E.g. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/nov/03/thousands-protesters-march-for-clean-water-london-sewage-pollution in November 2024. It has been suggested that the private Water Companies have paid out more in dividends to shareholders than has been invested in environmental improvements, and in the case of Thames Water, to bring it to the point of bankruptcy while still releasing more raw sewage and with limited action to reduce the enormous losses of treated water from its pipe network. At the time of writing, there is news that water bills will rise to fund improvements, but without any indication that returns to shareholders will be reduced.

- https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/what-is-the-sixth-mass-extinction-and-what-can-we-do-about-it. It seems that this is occurring even in the remotest parts of the Amazon forests, see https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jan/30/birds-dying-pristine-amazon-climate-crisis-aoe

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2025/jan/23/this-is-not-flyover-country-a-journey-down-americas-spine-in-pictures

- E.g. in https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/09/the-pleasure-of-the-search-for-the-unexpected/ and https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2011/07/featured-photographer-michela-griffith/

- See my previous article on walking in https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2024/06/the-road-not-taken/

- https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/08/nobody-expects-the-inquisition/

- See the article by Sarah Marino at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/12/7-principles-reduce-impact-nature-photography-wild-places/

- Such as in the images of Thomas Wrede and Ohan Breiding of the degradation of the reflective blanket that covers part of the lower Rhone Glacier in the Valais, Switzerland.

- And was a member of the Thetford Environmental Action Group in 1973. The Group did not last long, but does have an entry in the National Archives I was astonished to find.

- Simulacra et Simulations was first published by Baudrillard in 1981 in French. A good summary can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simulacra_and_Simulation.

- Actually written in 1968 when he was still with the Hollies, but not recorded until 1970 with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. The lyrics start:You, who are on the road

Must have a code you try to live by

And so become yourself

Because the past is just a goodbyeTeach your children well

Their father's hell did slowly go by

Feed them on your dreams

The one they pick's the one you'll know by - André Rouille (op.cit.) notes the important difference between the tradition of the auto-portrait (including in photography) with the intention of only limited circulation, and the selfie intended to be posted on networks with the intention of being dispersed as far as possible.

- https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2024/11/learning-to-see-again/

- The previous volume, The Landscape as Haiku, was introduced in the On Landscape article at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2024/04/landscape-as-visual-haiku/ . It is also available as a Blurb book or PDF at https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/11891565-landscape-as-haiku. The new book is called The River as Haiku and is available as a Burb book or PDF at https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/12348913-the-river-as-haiku. There is also now a third volume, Mallerstang Haiku, with images from my favourite valley in Cumbria. It is also available as a Blurb book or PDF at https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/12426797-mallerstang-haiku.