The Photography of John Wawrzonek

Ron Rothbart

I'm an amateur photographer living in the San Francisco Bay area. For awhile, I was very much into minimalist long-exposure photography. I must have photographed every piling, pier, and bridge in San Francisco Bay. These days I'm into natural landscapes. For me, going out to photograph is always something of an adventure. Even if I have a plan, I never know what I'm going to find. The experience of the shoot is as important to me as the result.

It is sometimes said that a photograph should have a prominent point of interest. Camera club judges sometimes ask, “What am I supposed to be looking at?” as a way of criticizing images that do not have such a point of interest. But isn't that an arbitrary requirement like the so-called “rule of thirds"? Photographer John Wawrzonek thinks so. “In most images, I deliberately avoid a prominent point of interest. I want the viewer to explore the image and to see the wonders of the details of nature."

Wawrzonek is a master of the intimate landscape. Since the 1980's, he has been shooting colorful small scenes, images of ground cover, pond plants, reeds, and frost-covered foliage. He has also photographed larger scenes, but usually with no prominent point of interest. William Neill has called Wawrzonek “one of the greatest landscape photographers of our time.” In an "On Landscape" interview, Claude Fiddler said Wawrzonek was one of the two photographers who most influenced him. Yet Wawrzonek, who is now 84, is little-known.

I just recently discovered his work. I happened to pick up one of his photo books at a hiking lodge and was blown away by some of the images. Wanting to see and learn more, I purchased his books (used because they are out of print), looked for his website, and gave him a call.

Like Ansel Adams, music was John's first love. He came from a musical household, learned to play the piano by the age of eight, and accompanied his father, who played violin. By his teens, he was an audiophile. At MIT, where he studied electrical engineering, his faculty advisor, Amar Bose, offered him a job as employee number five at his startup audio equipment company, now the famous Bose Corporation. Making music and making recorded music sound good was a precursor to his next profession, taking photographs and making high quality prints.

In 1974, while working at Bose, John bought a 4x5 view camera. At first, he did some fairly conventional landscape photography on travels out West, large scenes, mountains, waterfalls, the usual stuff. "Two lessons emerged: you had to go often to the same place to be on site when something special was happening, usually with the weather, and you needed time to explore. This meant shooting close to home." He also wanted to chart his own path. "I didn’t want my images to look familiar, and that implied no lessons but rather experimentation.... I began without a clear idea of what I wanted to photograph, except that I did not want it to be the usual places, the recognizable iconic views predominately in the West."

While he deliberately did not study photography formally, John did attend exhibitions. In 1977, he went to Eliot Porter's "Intimate Landscapes" exhibit in New York. Porter's was the first solo exhibition of color photographs ever presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A pioneer in color photography, he was one of the earliest adopters of Kodachrome, the first widely available color film, and dye transfer printing, which had been developed in the 1930s for technicolor films. Many photographers at the time were skeptical of color, including Ansel Adams, who thought of it as purely realistic, not expressive.

Wawrzonek loved color and at the time he started shooting, dye transfer was the only way to print brilliant color and control contrast, saturation, and brightness. It was an extremely complex, labor intensive, and sensitive process, but with his technical background and the help of an assistant, John built his own print lab.

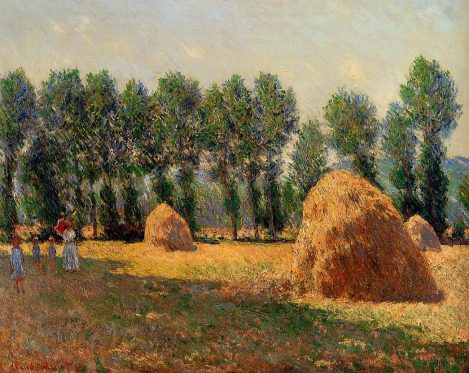

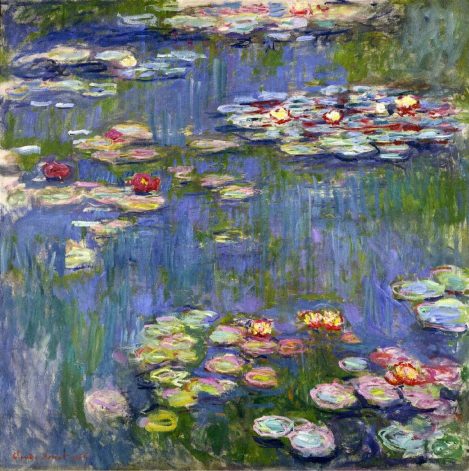

Another influence was Impressionist paintings. "I had attended every impressionist exhibit that came my way, but there was one, 'A Day In The Country', that was the show of shows." He especially liked the paintings of Claude Monet, the founder of Impressionism. Monet was famous for his many pictures of colourful lily ponds and haystacks. "Now I had an idea," writes Wawrzonek. "With a view camera on my back, the paintings of impressionists told me to look where other photographers had not, and to...let the nature of my New England home take me where it would. And it did."

Wawrzonek experienced a breakthrough one day in the Spring of 1981 when he discovered a particular view of some trees. "It happened that the only place to photograph these trees was from elevated portions of Interstate 90 a few miles west of Boston. This was a unique vantage point that placed me as high as the tree canopy as well as close enough to photograph. The trees in early spring became a pointillist ensemble of buds of various colors, some as brilliant as leaves in the fall."

"These images led me to seek other places and subjects where an ensemble of texture and color was the heart of the image.... I was amazed at what I found along major highways and ordinary roadsides. Without a distinct subject, the image often became something of a tapestry, seeming to extend without limits." This notion of a tapestry that extends without limits became a central feature of Wawrzonek's style. “Images contain a horizon only if it contributes to completing the composition. I also try to make the image extend without diminution from corner to corner, as if cut from an infinite tapestry.”

Eliot Porter had a similar idea he expressed in a different way. "Photography of nature tends to be either centripetal or centrifugal. In the former, all elements of the picture converge toward a central point of interest to which the eye is repeatedly drawn. The centrifugal photograph is a more lively composition, like a sunburst, in which the eye is drawn to the corners and edges of the picture: the observer is thereby forced to consider what the photographer excluded in his selection."

Not only intimate landscapes in general, but also this particular kind of image, a small scene that extends without limits, has become popular among photographers in recent years. In his focus on "infinite tapestry" and shooting locally at a time when large scenes in iconic locations were more in vogue, Wawrzonek was ahead of his time.

Another idea resonated with and reinforced Wawrzonek's interest in photographing locally, the notion of the "hidden nearby," which he derived from this passage in John Hansen Mitchell's book, "Ceremonial Time": "Wilderness and wildlife, history, life itself, for that matter, is something that takes place somewhere else, it seems. You must travel to witness it, you must get in your car in summer and go off to look at things which some ‘expert,’ such as the National Park Service, tells you is important or beautiful, or historic. In spite of their admitted grandeur, I find such well-documented places somewhat boring. What I prefer, and the thing that is the subject of this book, is that undiscovered country of the nearby, the secret world that lurks beyond the night windows and at the fringes of cultivated back yards.” This quote inspired Wawrzonek to write the following verse: “Out of the corner of my eye, in the ‘Hidden World of the Nearby,’ untended Gardens Thrive, Or pass from time Unnoticed.”

"The message of being aware," John writes, "being conscious of that which is nearby but hidden, is one of the most important guides to life as well as to photography. It took me over a decade of photographing to realize that I had to have an open mind, a mind without preconceptions, to see when I looked." Wawrzonek later used "The Hidden World of the Nearby" as the title of one of his exhibits.

Wawrzonek photographed throughout New England as well as the Great Smokey Mountains and further south, but some of his most memorable photography experiences were by the sides of nearby highways and roads, as well as at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts not far from where he lived, and in Acadia National Park in Maine.

Eliot Porter had used selections from Henry David Thoreau, famous for his sojourn at Walden Pond, in his 1962 Sierra Club photo book, "In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World". Decades later, colleagues of Wawrzonek's wife, who worked for the parks department, suggested that John photograph at Walden Pond. This led to eleven years shooting at and near Walden Pond and two books containing selections from Thoreau, "Walking" in 1994 and "The Illuminated Walden" in 2002. Thoreau's observations fit well with both photographers' attention to nature up close, as well as Wawrzonek's notion of the hidden nearby. Thoreau believed that beauty is often hidden in plain sight, concealed from us by inattention. We fail to notice not because nature is distant, but because we are not truly awake to it.

Nature will bear the closest inspection. She invites us to lay our eye level with her smallest leaf, and take an insect view of its plain. ~Henry David Thoreau, Journal, October 22, 1839

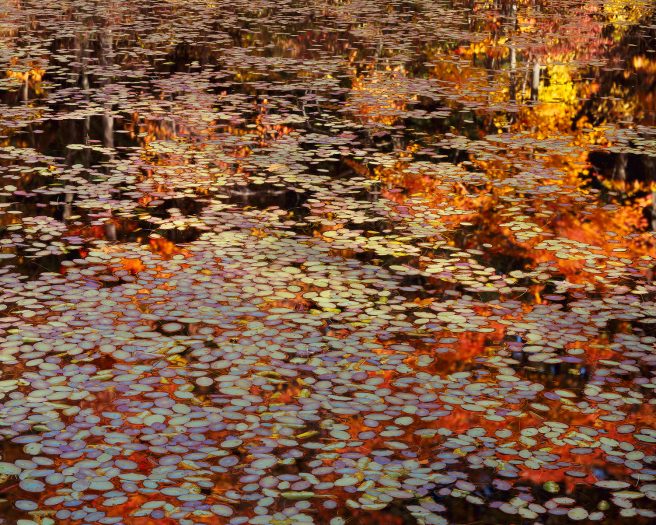

A particular meadow that Wawrzonek came upon near where Thoreau's cabin had been was a revelation. "When I stumbled on Wyman's Meadow, I went bananas." he says. What he found there was a vernal pond (a temporary shallow pool) with violet and green Water shields floating on the surface. Water shields resemble lilies but are actually a different species. Orange and yellow reflections from the sun and trees behind the pond added a beautiful glow complementing the water shields. Wawrzonek shot a whole box of sheet film that day. Although he returned many times over the next 10 years, those conditions never recurred.

Another vernal pond, Upper Hadlock Pond, beside a road in Acadia National Park in Maine, was also a favorite location. Wawrzonek discovered it on his first trip to Maine and visited it whenever he returned. It contained a patch of yellow, orange and green reeds that "has come to feel almost like family". It was windy on the day he found it. At first he was bothered by the wind, but then he realized the wind created "a kind of dance in which I participate." And on quiet days,"the reeds just line up to show their fall colors," reminding him of Monet’s haystacks.

Wawrzonek made very large prints of his Hadlock Pond photos showing the reeds in great detail. By the late '80s, he had gained a reputation for exceptional prints, and his print lab and gallery had become a successful business. Wawrzonek made much larger prints than were typical at the time. Unlike Porter, who considered prints larger than 16" x 20" to be wallpaper, John developed prints at sizes that were almost unheard of at the time. People told him they wouldn't sell, but they did. Over time, he sold prints to many hospitals, banks, corporations, and celebrities. In 1987, he printed and sold a portfolio of Porter's photographs chosen by Porter himself, sized 32" x 40".

When printing, Wawrzonek routinely made adjustments to contrast, saturation, and brightness. "This kind of manipulation is straightforward today," he writes, "but in 1983 when the photograph [below] was made, there was no Photoshop to fall back on, and so my reliance on dye transfer printing paid enormous dividends." In the example below, when shooting the image, he deliberately underexposed because he was photographing into the sun. When printing, he opened the shadows.

By 2005, Wawrzonek had switched entirely to digital photography and printing. After 30 years of landscape photography, he moved on, creating some outstanding floral work in his "infinite tapestry" style. Then, using Photoshop, he turned photographs of musical instruments into tapestries he called "lightsongs". In a sense, he was returning to his roots in music.

The days when people only saw a photographer's work as prints on a wall faded with the rise of the internet, and John began working on a website. But for years, it remained a sprawling work in progress, which may be one reason he is not well-known today.

John created another website as well, called "Caring For the Earth". His sensitivity to ecological and political crises goes back decades. Realizing that no effective action was being taken on climate change, he used this website to argue for wartime level investment in carbon capture along with an urgent effort to reduce emissions to zero. As an engineer who knows something about risk, he said, you plan for the worst case.

As time went on John came to feel that no one was listening, and the situation was hopeless. On top of that, Trump came to power. John had recognized the man for what he is back when Trump spread lies about Obama's birthplace. Now, as President, "Trump is showing us what he is made of. His poisonous brain is dismantling America. An insatiable longing for recognition, a monster who knows he is worthless...he will violate every legal and moral principle to get what he wants. If the Supreme Court does not stop him, it will be the end of America and possibly the destruction of the earth.... He will stop at nothing to fill the void that is his soul." John was talking here about the good old days of Trump's first term. But John was prescient. He knew what was coming. Sadly, this was enough to drive him into a very dark place, disturbing his sleep. His family worried and encouraged him to lay off the politics for his own good and return his attention to photography. He is now busy creating a new, simpler photography website.

If you'd like to get in touch with John for any prints or questions, please send John an email directly.

Water shields and Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts, October 1991 cat. 06321919

References

Bibliography

- John Wawrzonek, Walking: An Abridgement of the essay by Henry David Thoreau, The Nature Company, Berkeley, 1993

- John J. Wawrzonek, The Illuminated Walden: In the Footsteps of Thoreau, 2002, edited by Dr. Ronald A. Bosco, President, The Thoreau Society

- John Wawrzonek, The Hidden World of the Nearby: an unexpected intimacy, Images from the Exhibit at Olin College, Needham, Massachusetts, February-May, 2014

- Eliot Porter, Intimate Landscapes, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979

- Eliot Porter, "In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World," Sierra Club Books, 1962

- Video of and about Wawrzonek: an artist profile, cinematography by Claude Fiddler

- Juniper Haircap Moss, Wachusett Reservoir May 1994, cat. 4148

- Small-Singular Luminary, Ledges Trail, Baxter State Park, Maine October 1988 cat. 0265

- Untitled

- Haystacks at Giverny, Claude Monet

- Water Lillies, 1916 Claude Monet

- Peak Color

- Untitled

- Red Blueberry

- Water Shields and Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts October 1991, cat. 0632

- Wind and Water II (Upper Hadlock Pond)

- Upper Hadlock Pond Installation

- Spring Sunrise, Exit 11, Interstate 90, Millbury, Mass

- Melange Installation

- Untitled

- Stream with Rocks and Leaves, Cambridge, Vermont October 1977 cat. 0487

- Water-shields And Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts, October 1991 cat. 06321919

- Lichens And Teaberry Leaves, Acadia National Park, Maine September 1990 cat. 0397

- Lightsong