1914-18 - A Hundred Years On

James Kerr

James Kerr has been a commercial, garden and landscape photographer for over twenty years. Before becoming a photographer he spent seven years in the Coldstream Guards. His work has been published in several books on the Great War as well as ‘Shakespeare’s Scenery’ a coffee table book of Warwickshire with foreword by Dame Judi Dench. Silent Landscape was the perfect assignment that combined both his military and photographic interests. Following the publication of Silent Landscape he is taking parties out to see the battlefields for parties with and without cameras.

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

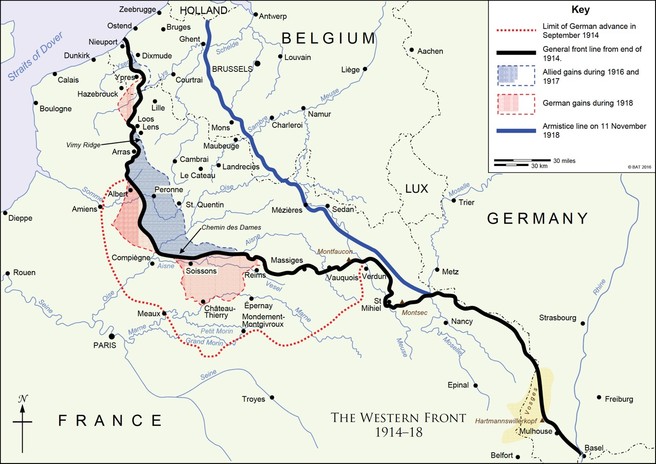

There are many books about the human experience and tactics of The Great War, but this one is different: it is an illustrated book about the landscape upon which the war was fought, relentlessly, over a narrow ribbon stretching across Northern Europe. All the explosive and destructive power known to man was used here, with success or failure being measured in yards rather than human cost. Time and again, battles were fought over the same ground until finally the old front lines collapsed after nearly four years, heralding a return to ‘open’ fighting, a short period when the heavy hand of warfare hovered just a little more lightly across a much broader landscape - Taken from Silent Landscape

Tim Parkin: Thanks for agreeing to an interview with On Landscape

James Kerr: Well, I’m now in that position having written the book, of having to tell people about it!

Tim Parkin: Have you had many conversations about it so far?

JK: The publishers and I on Twitter and that sort of thing. We have had one or two heavyweight people showing an interest. So we’re rather pleased

TP: Where did the idea for the project come from? Something you’ve been interested in for a long time?

JK: Let me take you back in my life. I started life as a young army officer. My “Damascus” moment was in Northern Ireland, in the 1970s when I was, in typical Army fashion, handed a camera and told to "go and use that!". I had that moment of ‘hang on, I’ve never been a photographer, know nothing about it’. It instantly clicked with me though and that lead to changing my career after one or two turns as a commercial photographer as few years later.

I’d been with Knight Franks, an estate agent photographer for very up market gardens and houses for about twenty years. A lot of that work was very interesting and highly enjoyable, somewhat stressful at times. But it gets formulaic and there needs to be ways of using your camera to express yourself. With a military interest and an interest in landscapes, the two served together.

TP: Where did the interest in landscapes start off then?

JK: I suddenly got it, if you know what I mean, I understood what cameras were about. I became very interested in photography. The landscape came because in doing estate agent photography, particularly with larger properties, it involves a lot of garden photography. With some sorts of garden photography there’s a lot of cross over. I did a book called ‘Shakespeare’s Scenery’ - a coffee table book of Warwickshire where I live, which came out in 2008/09.

I got Eddie Ephraums to do the layout for me, as at that stage I wasn’t skilled enough to do it. We got Judi Dench to write the forward and that was a sell out. With that I started to develop an interest and read up on his other compatriots such as Joe Cornish and Charlie Waite. I started getting up early in the morning, tripod mounted with a decent camera.

TP: When was this?

JK: It was quite recently around 2000. As an estate agent photographer from the 1990’s onwards I tended to us an Arca Swiss 6x9 rollback, which I loved dearly. With technology changing fast in 2004-5, the Canon 1DS came out and that was the first decent full frame format camera and that was when I made the switch. The Arca Swiss had to go on eBay to fund the 1DS!

TP: A very sad day!

JK: Yes, I loved that camera! One had to be practical though. Through having bought into the Canon system, with several lenses, I’ve stayed with them and have been very happy. I have had a Mark I and Mark III, and last autumn I switched over to the 5DS. I didn’t get the 5DSR, as I still do a certain amount of commercial photography and I needed a more all round camera.

TP: Where did the interest in military battlefield photography come from?

JK: Having been a soldier, I had been to battlefields many many years ago. But in 2008/09 I went on a four day trip to the French battlefields with a guide and group of people. I suddenly realised the photographic possibilities of taking serious photographs in the Somme and Ypres and across of the whole of the western front. A quick look in a book shop such as Waterstones will show you that there are reams of books on the First World War. And there are lots of people with photographs but nobody as far as I could see had done a book with more emotive photographs. They were mostly non-photographers taking a picture of a field.

TP: More documentary photography?

JK: Yes, that is more what it looked like. There was no feeling of something terrible has happened in this place. I felt strongly moved to see if I could rise to the challenge of producing emotive photographs.

TP: What was involved in that?

JK: From then on, this project morphed in my mind. A couple of trips on my own to really discover where I was going and to start to take photographs. What I would tend to do is spend the day reconnoitring a particular part of the battlefield. Then I would wait till either evening or dawn to revisit it having decided on potential camera angles. The results were often opportune - the sun comes up slightly different to where you expected or you see an angle that you hadn’t seen whilst scouting. Sometimes they were planned and worked absolutely to expectations. Which is what I’m sure most photographers discover when they go out and the light is right, you know it and all sorts of opportunities present themselves.

TP: When you started this project - what sort of creative changes happened as you went along?

JK: As a photographer you’re always on a journey and that journey never ends and so you want to refine your techniques. I use a solid tripod, like most landscape photographers and use a shift lens quite a lot. I enjoy using it to improve the depth of field. There are three or four images in the book, where it’s a pile of mud with a shadow in it where being scheimpflug technique to great effect to produce a pin sharp photograph.

TP: That’s quite apt really as Scheimflug developed his technique for photographing battlefields in the First World War.

JK: There was a cinematographer called Geoffrey Malins and he produced a black and white film of the Somme. This film had more viewings than any film until Star Wars in the 1980s and you’ll know bits of this if you’ve watched anything about the Somme on the BBC. You’ll see a chap clambering out of a trench only to suddenly fall back or there’s an explosion which people show. Well I’ve photographed both those areas and they are in the book, so people can see what the land looks like now compared to the footage in the film or the stills that you will see around.

TP: In terms of the construction of the book and the narrative flow of it, what were the decisions which went on?

JK: I needed somebody to write the book, as writing is not my strong point. I teamed up with somebody that I met in the Army who was a military historian, a chap call Simon Doughty. He also was the editor of a regimental magazine called The Guards Magazine and was a battlefield tour expert. Towards the end of the project we would actually got out together to photograph and between us we would decide where we would be going.He would then make his notes and I would get up early in the morning to take the photographs. He was able to provide the copy for the book and there was about 30,000 words, which is quite a lot. So when you see a photograph, there is a paragraph tell you what happened there. I hope people will enjoy the work.

TP: Do you see it as an informative, documentary book or an art book?

JK: That’s a very interesting question. In my heart of hearts, I would like to have done an art book on a large scale, but having to interest a publisher, I have had to compromise slightly, to produce a book which the publisher wants to publish. That has obviously, meant that several of the photographs had to be cropped in a way that I wouldn’t have chosen, so there have been compromises. The end result though I’m pleased with and I hope, to a certain extent it straddles both.

TP: Getting a publisher these days isn’t the easiest of tasks. How did you go about this? Did you get a publisher first?

JK: I have to say that Simon who wrote the book, had a relationship with two or three publishers, as he has written stuff in the past. He was able to approach people much better than I could and we have published through a small publishing house called Helion who are specialists in military publishing. It’s their first venture in what they would consider to be an art book, rather than a pure textual book. So it’s a learning curve for them as well.

TP: Where’s it being printed or has it been printed already?

JK: It’s due in a couple of days; great excitement. It’s been printed in Malta through one of their contacts. I just hope it’s all going to come back looking nicely printed.

Ther are a lot of things like where you have had to crop a picture because of the crease in the book, that sort of thing are the compromises we have had to make. That’s inevitable when you have a book that has to be a certain price with a general market to sell to.

TP: Any book publishing is going to be a compromise of all sorts. Even if you think you don’t have any compromises!

JK: You will have! We started off with 250 page book and was really pleased with it but because of the price point we had to cut a lot. Which in fact was a very good exercise, as it made you think hard. That said, another ten pages would have made an enormous difference, but I’m pleased with the result.

TP: Did you do the preparation work for the book?

JK: I am an amateur on InDesign and I designed 90% of it myself. Then it had to go to their InDesign person who tweaked it to get it right. I’m not good at getting copy exactly accurate in the right place and format. The actual art or creative element was mine though.

TP: So you must be quite excited then?

JK: It was an enormously satisfying task and I’m really looking forward to seeing it!

TP: When does it go to retail?

JK: Book launch is on the 8th June,6.30-8pm in Chelsea in London at Daunt Books, which anyone can come along to if they are in London. I wouldn’t recommend anyone driving half way across the country! It will be available to buy through Helion or autographed copies through our own website.

One of the spin-offs from the book is that we are taking people on battlefield tours and the first one is already sold out! I’m thinking about the whether people would be interested in a specialist photographic battlefield tour. Which would be taking people out there who are keen photographers, as I think as a landscape photographer, you need more than just landscape - you need an interest in why you’re taking that photograph. Otherwise, it can get a bit nebulous - is there any depth to it, what does it mean, is there a message you want to get out there? Battlefields are very emotive places.

TP: I remember there’s one picture from Charlie Waite’s which is a set of trees, which are very evocative, which a wheat field in the background.

JK: If I have an influence, it is Charlie's work, because he had a lot of human influence in his photographs. There would always be a little house or something which is manmade in the picture. That relates to garden photography where you get the formality of the garden, but there will be a gate or something. I’ve been to Rannoch and Skye and taken a few pictures and had great fun but, that sort of photography has been done many times. One’s looking for other avenues to express oneself.

TP: I agree with you on doing something interesting or having a projects it makes a lot of sense.

JK: I think it’s very important. My first project was Shakespeare Scenery was Warwickshire, Stratford Upon Avon, Warwick Castle, all that sort of thing. The First World War and with the centenary coming up was another spur to do it.

I was reading in one of your recent issues the article on Aspect Ratios which was written by Joe Cornish. I found this article intriguing, because having done so much work on 6x9 which was the roll format on the Arca Swiss. For a lot of landscapes it works quite well as a double page spread, which is one of my favourite formats. If I’m not using that then I tend to go square or 5x4. If I’m shooting vertically then I tend to crop top and bottom. I’m not like Cartier Bresson who refuses to crop!

TP: So can you pick out three pictures from the book and tell me a little bit about them - not necessarily the history, but your experiences in taking them.

JK: I certainly can - here you go....

Mash Valley, Somme

Mash valley is featureless and open skied; an unremarkable agricultural landscape. A former killing field for the hapless British, it needed some human scale to tell its story. Fortuitously this was provided by the tractor. Taken in the evening in almost monochromatic light the image was cropped to a 16:7 aspect ratio to emphasise the wide-open space.

70-200mm F11 at 1/30.

Langemarck German Cemetery, Ypres

German Cemeteries are not as well known as the British ones. They are desolate and darkly Wagnerian in character. To emphasise this required a predawn visit with an early morning mist luckily I got what I was looking for on my first attempt. I used a 24mm T/S lens with a little upward shift set on a low tripod to accentuate the verticality of the shrouded trees. F11 at 1/6.

Massiges

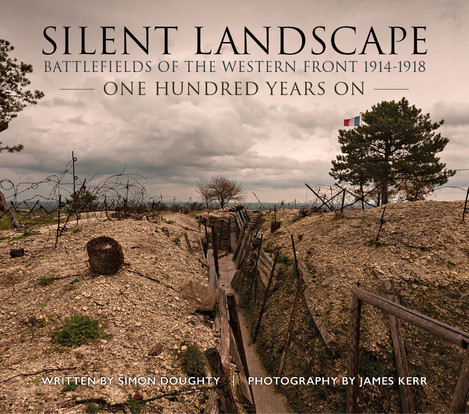

Almost unknown to the British is this small section of the Champagne battlefield that has recently excavated by local archaeologists. I arrived hurried and harassed having got lost trying to find the place. Conditions were near perfect with leaded clouds gently drifting across the scene and my favoured monochromatic light. Setting up the tripod and using a gentle ND grad filter to bring out the clouds, I was timely with my first few exposures. Within minutes the moment had passed as the light faded into darkness. I liked this one so much that we used it a version of it for the front cover of the book. 17- 40 mm lens at 20mm, F10 at 1/25.

Mesnil Ridge and Knightsbridge Cemeteries, Somme

As the passenger in an open aired micro-light it makes good sense to prepare properly before you get airborne, a lens change at 300ft is definitely forbidden! I wanted to show how isolated and peaceful are some of the British cemeteries on the Somme. An aerial shot highlights this and the gentle sweep of the curved track reinforces the geometry of the picture. Taken deliberately when there is only ploughed earth, as the normal maize crop would have cluttered the image. Taken in bright morning sunlight.

24-70mm lens at 50mm, speed priority: F7 at 1/500 ISO 250.

Signed copies of the book are available through www.silentlandscape.com or through publishers www.helion.co.uk - £25.00 + postage.

[/s2If]