Featured Photographer

Ellie Davies

Ellie Davies (Born 1976) lives in Dorset and works in the woods and forests of Southern England. She gained her MA in Photography from London College of Communication.

Davies is represented by Crane Kalman Brighton Gallery in the UK, Dimmitt Contemporary Art in Houston Texas, Patricia Armocida Gallery in Milan, Susan Spiritus Gallery in California, Gilman Contemporary in Sun Valley Idaho, A.Galerie in Paris and Brucie Collections in Kyiv.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

Back in July 2016 On Landscape included a piece that Ellie Davies had written about her then forthcoming exhibition 'Into the Woods' at the Crane Kalman Gallery in London. Ellie has been working predominantly in forests since 2007 exploring both her own and our wider, relationship with them and with the landscape. Her images have reached a wide audience, and we thought it would be interesting to talk to her about her work and about the way in which we perceive nature and the landscape.

MG: Would you like to start by talking a little about yourself and telling readers about your background?

ED: I have always been interested in photography. My dad had a darkroom when we were young. He and his best friend were very interested in black and white photography, and they taught my sister and me to print. Then I did a lot of sculpture at school and thought I was going to be a sculptor. I did an art foundation course, and quite quickly I realised that I wasn’t sure how to be a working artist at that age. I went on to do a psychology degree, which I loved, but I didn’t want to become a psychologist. It was more a way of trying to find out about where I was going to end up. I really missed making things, and I managed to get elements of creativity in my life by doing a bit of sculpture and jewellery making. But I was just desperate to get some creativity back as part of my work.

I moved to London and assisted lots of photographers before taking some commissions and doing some magazine work. Quite quickly I realised that I’m not that good at realising other people’s ideas; I didn’t enjoy it that much and what I really wanted was to explore my own ideas. I did an MA in photography at LCC (London College of Communication), and that was two years part-time. We had to make one body of work through two years which I found excruciating. I like to work quite quickly. I am often thinking about or making several ideas or bodies of work alongside each other. They sometimes merge into each other, and different things arise as I am making them.

It was a hard process, and I came out of it realising that I wanted to work in landscape photography. It was a way of thinking about the different balances of power within the image without the need to necessarily use people in the images to explore those themes.

MG: Looking back at your early work, I was interested that you started looking at the relationships between people and the landscape was effectively a set. At some stage, the trees replaced the people, but the landscape is still your set.

ED: Exactly, it was hugely liberating to realise that I could go off on my own and work alone, which I love, without the whole production element of taking people, and all the props and planning that working with other people entails. I love working with people because it brings collaboration and an element of surprise to the process which is often the most interesting part of it, but working by myself was very freeing. Just to go off on my own and explore the woods, walking and imagining without a time scale or anyone to answer to in the process was wonderful.

So the landscape formed a studio space, in which I can introduce different elements to suggest different things in the same way as I would if I was using people. Often in my really early work, I used myself as a model. So to go back to working alone in that way, though not being in the pictures, was fascinating.

MG: I was quite interested to read that you still describe what you do as landscape photography because your work is very different from what most people’s perception of landscape photography is - that it’s about representation. You’re not looking at the elements of the landscape but at our relationship with the natural world.

MG: Yes, it is, and that’s something that I think at On Landscape we’re very keen to show people and to talk about. That it is a lot more than a calendar view which can often be a common perception.

ED: Definitely, but because photography is the result of capturing an installation or intervention I have made in the woods, or simply the woods themselves, I feel that my work is definitely photography rather than sculpture, although it has a sculptural element in it. For example Come With Me, seven where I used bracken to make a pathway through the woods, was featured in a sculpture trail at High Heathercombe on Dartmoor where it was installed in the woods amongst lots of other sculptures. There was a temporal element to the work as the bracken died back over a period of six weeks or so. So the people who came to visit viewed it in various stages of decline.

For this piece, I loved going back to a purely sculptural process, but for the rest of my work, the final result is always the photography. I definitely see myself as a photographer rather than a sculptor.

MG: That’s quite an intriguing image that one isn’t it, perhaps more than the others, as it makes you stop and think well did it grow like that or was it placed like that?

The other thing that comes across in your work is that you’re challenging our perception of our landscape as a product of nature and highlighting the fact that it is as much and in some cases more, a product of man.

ED: It’s really hard in the UK to go anywhere and not see elements of interference by man.

MG: That’s very true. The other thing which strikes me is that ‘fantasy’ keeps reoccurring either as something that perhaps you or we are escaping from or are drawn towards.

ED: Definitely. Well for me it’s something I’m drawn towards in the sense that our understanding of landscape comes through all sorts of different mediums. It all starts with childhood fairy tales and that magic of going to the woods as a child and playing, building dens and hiding. I took my son to the woods last weekend, and he was running around in the bracken, and he was much smaller than the height of the bracken, so it was really easy for him to get lost or to hide from me. It made me remember how tiny you can feel in the woods when you’re small and how easy it is to get lost in your own imagination.

MG: I think that’s one of the interesting things about photography, that it’s almost taking you back to see through the eyes of a child the way that everything is new and wonderful and interesting. We get out of that.

ED: We do, particularly now when we’re so saturated and bombarded with imagery. I’m trying to find my way back there to those early sensations of something new, a new experience or at least refreshing that memory of just going off in your own imagination. I remember those feelings of playing as a child, of almost waking up – though I was awake - and realising that I’d been so deeply engrossed in a game or a story in my mind. As adults, we don’t get time to do that anymore. But you can go to the woods and spend time sitting down and listen to the birds and it envelopes you. You can free your mind in a way and let it wander. Modern life can be so distracting and so full of stimulants to the point that it’s very hard to get to the point of being bored or to just drift off into your imagination.

MG: Am I right in saying that you grew up in the New Forest? From what you’re saying that was obviously very formative to you and I think you still mostly work there. Presumably, it’s quite important to you that you know your set very well.

ED: It is, but the New Forest is a big place, and I certainly don’t feel like I’ve explored it all yet. It’s an area of great variety and all sorts of different landscapes, at every turn you’re looking at something completely different. There are heathlands, plantations, ancient forests, newer forests and grazed areas, so it’s very varied. The colour palette is quite different from anywhere else I know in the UK. I’ve just moved to Wareham in Dorset and the experience of driving from Dorset which is incredibly green, or from London actually; you arrive on the borders of the New Forest and the palette changes to greys, browns, purples and muted greens. Because of the heathlands you get a totally different range of colours, I just love the muted, earthy colours. And obviously you’ve got the sea; the light is lovely as you get closer to the sea. I feel like I’ve got a great deal more to do there, I don’t feel like I’ve exhausted all the possibilities.

MG: I think even with smaller areas, sometimes you just need to see with new eyes don’t you? There is always something different, but it’s a case of how well we perceive that.

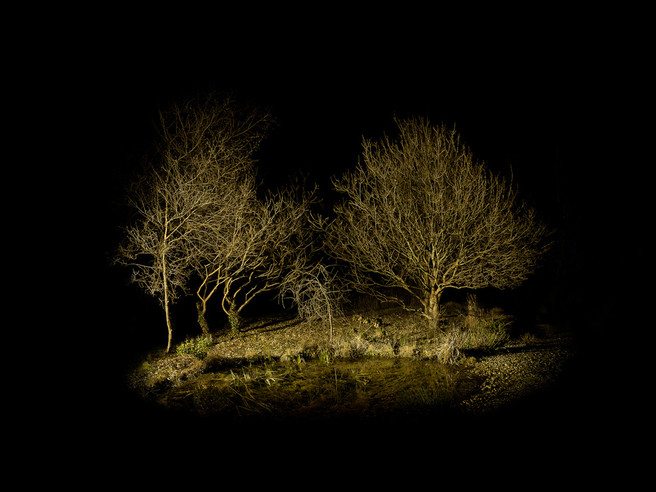

ED: The more you can visit, the more you can see things differently – in a different light, in different weather. It’s often about taking the time to sit still or lie down somewhere for a bit and really look. I feel very fortunate that I’ve finally moved out of London after twenty years and although I love London and I still go back there a lot, I have this wonderful proximity now to the New Forest. I also go to Puddletown Forest in Dorset and to Wareham Forest which is a new area to explore this winter. I’ve been looking at Wareham and at the woodland along the River Frome. The Half Light series is very much about rivers intersecting with the landscape. That was based in the New Forest last winter, and I wanted to carry on with that series and keep on seeing where it went. I don’t feel that it’s finished and I’m making some new work for that at the moment.

MG: Yes, I guessed that’s perhaps where you were the other day. As you’ve touched on Half Light, do you want to talk a little bit more about that? Your two most recent series Stars and Half Light both touch on the alienation that urban populations have increasingly from nature.

ED: When I was living in London the woods were always somewhere I longed for and loved to go to as soon as I got out into the countryside. But these short visits just were not the same as when I was a child and lived there. My sister and I would go out in the woods almost every day, and we felt we had some sort of ownership almost; it’s yours because you are there all the time and you occupy it. I really miss that relationship and that comfort. I was talking earlier about how the woods have this wonderful soothing quality, this liberating effect on me, and on everybody, I think.

MG: It’s a pretty good detox isn’t it?

ED: I would say so! With the Half Light series I was using the rivers visually as a way of demonstrating this wide barrier, it’s very hard to cross these rivers as they are deep and dark and it’s cold. I was often standing in the water making the photographs, but there’s no way to get across to the landscape beyond. I fell in the water a few times actually, getting in too deep for my waders.

MG: Hopefully no expensive accidents with your camera?

ED: Thankfully not! The camera was fine; it was usually just me that got wet! I made that series entirely in the New Forest which is quite rare for recent bodies of work, mostly I’ve worked in several different forests.

New things crop up, and that’s why I want to keep working on this series. I made Half Light during the first half of last winter but then my father was very ill, and while he recovered miraculously it meant that I had three months when I couldn’t really work on the series at all. I came back to it in March 2016 knowing I had a solo show where I wanted to show this work in June that year, so I had to get the work ready by May in order to get it all framed in time. I really wanted just to have a bit more freedom to explore where the series might go, so I want to keep adding to it again this winter.

I made some more work this week, and I usually put it all on the computer and then don’t look at it again for a few weeks because the experience of making the work is so integrally a part of me that I can’t be objective about an image. So I need a bit of distance to come back and look at it with fresh eyes.

MG: That’s something quite a lot of people say that they find is a benefit.

ED: For sure. I’ll have a look at what I shot in a couple of weeks and see what I’ve got. Maybe carry on with that for the early part of this year and then I’ve got a couple of other ideas..

MG: One of the things I was going to ask you was about the process of conceiving and making images for a series, and whether the story or the idea comes first or the images? From what you said I get the impression that you like to go out with perhaps some ideas in mind, but you very much respond to what you encounter rather than looking for things that fit your ideas.

ED: I often have a central idea, like for example for the Come with Me, 2011 series I was making pathways in the woods. I have a campervan and took lots of different materials that I thought I might useful, but I ended up using a lot more natural materials. Then for The Dwellings series, I was using materials gathered from the surrounding area. I was very much responding to elements in the scene, the colours, shapes and composition within the woodland, and referencing them in my choice of materials. For one of those large structures, I needed a tree that was at exactly the right angle so I could start working into it. Actually, I got my husband to help me with some of the initial framework as it was often a case of lifting tree trunks and I was pregnant for most of that series. So he’d come and build the initial triangle, and I’d build the rest and then come back later to take the photographs.

So it really depends on the series, and I think that with the Half Light series more than any other, it’s just as you say, it’s very much about walking and responding to the environment I’m in and discovering places that will work with the series. I did a lot of research finding rivers that run through wooded areas - Google Maps is amazing for online planning. It often depends on the time of day and the angle of the sun as I usually like to have the sun behind me even if the weather is awful. So all these factors enter into the decision about where to work, but I like to try to be as flexible as possible. It’s a great way of exploring the forest as well; I take a picnic with me and just go off for the day, and I feel very lucky that I can do that for my work.

MG: Do you tend to work away from the paths and the busier areas? I wonder if sometimes you do on occasion encounter people and what reaction you get from them?

ED: I sometimes do, it varies. I try and keep away from people because I think that what I’m trying to do is create an atmosphere of contemplation in the work, and if I’ve got people crashing about…. I sometimes get people coming up and asking about my camera, and that’s quite intrusive when I’m trying to concentrate. Sometimes I meet people who are working in the woods; I met a rat catcher once, and he was quite an interesting character. I’ve had a couple of people shout at me because they thought I was littering the woodland. For Come With Me, there was one image where I’d cut hundreds of paper leaves, and I’d laid them on the forest floor, and I was photographing them, and a woman came along on her horse. I think really I gave her a fright as she wasn’t expecting to see anyone and she got quite cross.

I’m meticulous about cleaning up after myself as it would be totally against my way of working to leave anything behind or cause any damage of any sort. It’s rare to meet people, and mostly they are very nice and quite interested in what I’m doing. For the Between The Trees series, I made a particular effort to keep away from people because I was using smoke and I didn’t want it to drift across roads. Often if it’s pouring with rain – and I made a lot of that series in the rain - it’s very quiet in the woods. People often stick to the paths as well so if you take a few steps into the dense woodland you are generally on your own. You don’t have to go far to feel quite isolated.

MG: I was interested that you said that you studied psychology and that must be fairly integral to the work that you are creating, both in terms of the ideas you are generating but also in terms of the tension that exists between how much of the work is about yourself and how much is your observation on the state of man.

ED: I’m sure that’s all in there, but it’s hard for me to pick it apart and say one thing came from one element of my experiences. I think that maybe I’ve drawn less from the psychology degree itself than from a women’s studies module which really got me interested in reading about women’s experiences and in the power of different gazes, ‘male gazes’ in particular. That was something that really preoccupied me throughout my degree and stayed with me in terms of thinking about the way we look and experience the world around us. I’m sure that’s had an influence on my work.

MG: The other thing that interested me as I was looking back at Smoke and Mirrors where you were placing a golden tree in amongst a forest or wood was the idea that beauty isn’t always about truth.

MG: You’ve looked as well at the role of the light and dark in terms of safe space and our perceptions of darkness, but also negative space – I’m thinking about Silent Dark and Deep - about what don’t see and boundaries.

ED: Well those are implied spaces aren’t they? So they are a psychological space, it’s about the other-ness of our imaginations. I like to allow that space for the viewer to go down those pathways on their own. Each person brings something different depending on their experiences, and I really enjoy the fact that people who look at my often work react very differently. Some people find certain bodies of work sinister, almost upsetting. Sometimes, to my surprise actually, they have such a depth of feeling. And for other people, it takes them to somewhere in their imagination where it’s really positive and magical. You don’t know how someone will react, and that to me says a lot more about the viewer than necessarily about my work. I’m just giving them the opportunity to explore those ideas themselves I hope! It’s also about my experience of being in the woods and how it makes me feel, and I hope I can bring that to my work.

MG: When you were saying that I thought that their reaction is perhaps influenced by their own history and their relationship with nature. A lot of it happens at a subliminal level. You were talking about creating work, and all these experiences and influences come in without necessarily being conscious of the thought processes involved.

ED: Absolutely!

MG: One thing I wanted to ask you was if there was anybody who has been particularly inspirational to you - a photographer or an artist or an individual who’s influenced your own development or whose work you particularly admire?

ED: I was really interested in land art when I was young, and you’ve got all the big figures such as Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long. People do sometimes reference these artists in relation to my work, and I know that’s something that everybody who does photography will have come across. The problem of creating something new in a world where it feels like every image you could ever make has already been made. Trying to find your own view of the world is something that you have to develop. As a student and when you start to make bodies of work you try and find your own voice in amongst all of that. I talked to you earlier about making lists in books and compiling ideas and I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve written something down and then thought, no I’ve seen that before. Or having made work and opened up a photography magazine and seen an image that’s actually the same thing that I had in my mind.

It’s like there’s a collective conscious that creates ideas in different people at the same time who are totally unconnected. It’s just staggering how this can happen. I’m not somebody that goes to lots of exhibitions or reads lots of information online about other artists. I feel like I’m relatively working in a vacuum, but then I can find that I’ve had an idea and then somebody else has already done it. You think “How is this possible?!” That’s hard I think. However, I love the fact that people have referenced Andy Goldsworthy as I love his work and he’s a totally incredible artist, and for me, he has been an influence. My mum had this amazing book of his work when I was young, and I used to go out and smash the ice on our pond and try and build some small replica of his amazing balanced archways of ice. I think he was a big influence.

MG: Maybe it’s a case of it’s about the work, it’s about the images and your relationship with them as much as the person who created them.

MG: A question here from Tim. Andy Goldsworthy plays down the role of photography in his work (referring to it as "routine" and "the leftovers of my work"). Do you see your photography or your sculptures as the dominant in your works of art? A trick question as I'm sure separating them is impossible, but it's something that has played on my mind for some time about ephemeral works.

ED: I definitely see myself as a photographer, and the sculpture is an integral part of that, but not essential. In my recent Half Light series, I didn’t make any sculptural intervention, but the work continued to explore the same themes as older works. It was interesting to see how far I could remove myself from the process while continuing to explore my relationship to the woodlands and forests and my experiences of them.

MG: You’ve had quite a busy and a good year – I’m thinking about the Aesthetica Prize shortlisting for Stars, and lots of magazine features have come from that. Exhibitions as well. What’s particularly excited you from all the good things that have happened over the last year?

ED: I was interviewed by National Geographic last summer and had my work on their website. That was wonderful, a dream. Not something that I’d thought would happen actually! It opened up my work to a huge audience that I wouldn’t otherwise have had access to. Lots of teachers wrote to me, mostly from the US, with lovely letters and emails saying they had discovered my work via the article and the students had found it inspiring, that is the best possible feedback.

Working towards my solo show with Crane Kalman Gallery this summer was a big fixture this year, and it was great to see the new series printed really big. Dimensionally the Half Life series is bigger than anything else I’ve done before because at the beginning of last winter I got a Pentax 645z and that for me was the first affordable medium format camera that I could buy and call my own. That definitely opened up a whole lot of possibilities.

Then the Singapore International Photography Festival – it was wonderful to have my work shown there this autumn. Crane Kalman Brighton Gallery is continuing to take my work to different parts of the world and open up new opportunities for me. This year we started working on a more formal basis. We’ve always had a great working relationship, but previously their representation was quite informal. That’s been great for me as the gallery has taken on a lot of the liaising for book offers, the logistics of negotiating the use of my images for different things, not just for print sales, and exhibitions abroad, things like that. They are handling all that for me now which actually is wonderful.

MG: You mentioned book offers, and I think you made a book through an online platform, called Into the Woods. Do you want to say anything about your experience of creating a book from your work?

ED: Yes, I made the book during 2015. I’d always had in mind that I’d like to see my work in a book format. I’d talked to various publishers, most of them seemed to expect the artist to contribute a large chunk of money and then they do a print run of say 5,000 books. They design it and then distribute their 2500 copies, and the artist gets given the other half of the print run. Well, I don’t have the space to accommodate that many books let alone the outlets to sell them plus it’s a vastly expensive thing to do, and it just seemed completely unfeasible. I talked to friends in the publishing industry, and they said yes, this is the way that a lot of publishing is going with photography books. It seems really sad to me, and most artists don’t have the resources to do that, but these were the sorts of offers I was being made. I knew that wasn’t something I could do.

So I decided to look at self-publishing and I really liked the things that I’d read about Bob Books and their interface that allows you to download an app and then just build the book yourself, and it’s really easy to do. I worked with Miranda Gavin (Hotshoe Magazine) who wrote a piece for the book - I’ve known her for about ten years now. Overall it was a relatively painless and very enjoyable process. It sells through the Bob Books website. It’s a great way for artists to work because you don’t have any costs involved really, just your own time to build the book. Then anyone who wants to order one goes to the book’s website orders the book and it comes straight to them in the post from Bob Books. I take a tiny (like £2) fee for each book that’s sold rather than looking to make a profit. I wanted to make my work accessible to people who don’t want to spend lots of money buying a fine art print. I sometimes buy art books and chop the pages out if I like the image enough! Books are beautiful things, and I know some people feel they are sacrosanct but it’s quite interesting to do different things with them, it’s just another way of experiencing a book. I love the fact that if someone says “I can’t afford your work”, I can offer them another option.

MG: It also works for people who can’t get to the exhibition as well as they can be on in places remote from people, and have a finite period, and it gives the work a life beyond.

ED: Yes. Recently I’ve been involved with Little Toller Books who are based down in Dorset. They have put together a compilation of wonderful writings about woodland called ’Arboreal’ and my image Stars 8 has been used as the cover image, and there are plates inside as well. The writers inside include some incredible authors. I was really honoured to be part of that publication, very exciting.

MG: That sounds like a good one to look out for?

ED: Yes, look out for it! It’s pretty thrilling for me to be involved. We’ve got Andy Goldsworthy in there, Dave Nash, Richard Mabey, William Boyd, Ali Smith, all writing about woodland. That’s out now through Little Toller and Amazon, and it got a great review in the science journal Nature recently.

MG: I was going to ask you if you have any particular plans or projects or ambitions for the future but I get the feeling you probably have quite a lot and it’s just a case of which ones you can take forward and when you can do that.

ED: I’ve just moved to Dorset, so now I can take my son to school, go to the woods and be back in time to pick him up. When we lived in London, I had to take the family down to my mums in the New Forest, and quite a few things would have to be in place in order for me to make some work. The weather would have to be right, I’d have to have my materials organised, and the idea sorted out, the patience and time…. Often I’d get everything in place and get to the woods, and the sun would come out all day! It was extremely frustrating. I’m going to be able to get out in the woods a lot more, so yes, lots of things bubbling up in a way but apart from seeing where Half Light goes in the next few months, there’s nothing concrete. I’ve got a solo show in Ireland this Spring at the Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre in County Londonderry and work in a group show at Houston Center of Photography in Texas, US opening in March.

MG: I think I read somewhere that one of your other interests is rock climbing. Is that right? Do you think that as far as you can see that you’ll always work in woodland or do you think there’s any prospect that you might take your work into other places?

ED: Yes. Possibly! I don’t know how. I’m certainly enjoying working in woods at the moment, but I don’t want to rule out working in a different environment. Climbing takes you to amazing places; I’m always looking at the rocks and wondering how I could do something with that landscape. Down here we climb on the sea cliffs at Portland, and I’m often wondering what I can do with the sea and cliffs, the boulder beaches, those edge-spaces.

MG: That’s great Ellie, thank you. I think we have covered most of the things I’d made notes on.

ED: Thank you so much for interviewing me. It’s been lovely to talk to you.

MG: It’s one (interview) Tim and I thought would be interesting. We’re very keen to try to encourage people to think more broadly about landscape and where photography can take them.