Learning To View Your Images Objectively

Chris Murray

Chris Murray is a full-time photographer, instructor, and writer from New York State. His photographs are not meant to be a literal document of the woods, mountains, and rivers of his home state, but rather a creative expression of his relationship with the places that ceaselessly inspire him.

Identification with the work is a subtle and insidious phenomenon, one that we all are prone to experience to some degree. We view the work - rightly - as an extension of ourselves. Yet we cannot become the work. We must maintain a critical distance, and be capable of a more objective relationship with the content of our efforts. ~ David Ulrich

There is an old joke that the difference between a professional and an amateur photographer is the size of the wastebasket next to the light table. Granted, this was from the days of slide film, but the tenet still holds true. One of the defining characteristics that separate the professional photographer from the amateur is the ability to honestly and accurately critique one’s own work. It is also one of the more difficult tasks to master.

Learning to self evaluate one’s work is an extremely important exercise. A photographer's reputation is built on the images that she/he puts out into the world, whether it’s to editors or other potential buyers or simply the public at large. Sending out mediocre images shows an inability to discern between good pictures and bad. Worse, including lesser quality images with your best work in an exhibit or portfolio has a diluting effect and reduces the overall impact. Our work is only as strong as the weakest photo in the collection.

Self-critique requires us to be brutally honest with ourselves. It is often suggested by friends and family that I am too hard on myself with regards to my photography, and I understand how it can appear that way. But if not me, then who? If I listened to them I would believe myself to be the best photographer in the world, bless them. Truth is, all artists must have a critical eye when it comes to their work. We know when we have created something special, but it is just as important to know when we have failed, as much as we may try to kid ourselves. In order to learn and evolve as artists, we must be able to critically evaluate our work. It is easier said than done, as it can be difficult to cast an objective eye on our own creations.

Relying on Others

We all at one time or another have experienced the sting of posting a photo of which we are especially proud on social media, only to have it garner a tepid response. The first thought is one of confusion and disappointment. Is it not as good as I thought? Was I kidding myself? Or perhaps, is it the fault of the audience? Is it too challenging to appreciate, requiring time and reflection in which to be understood? All too often the latter may be the case, which is the danger of relying on social media for feedback. As photographers, we cannot treat our potential audience as if they are all equal. We must work to establish an educated audience, one that shares our sensibilities and is willing to put forth the time and effort to view and understand our work. And of course, saying that social media is a less than ideal platform for sharing our work is a tremendous understatement. The physical limitation of tiny screens coupled with the barrage of images posted daily all but discount it as a viable forum for opinion and feedback.

But, what of the educated audience? Can they be counted on for a fair evaluation of our work? The answer is maybe. Portfolio reviews with an established and respected photographer may provide informative and useful feedback, but there is no guarantee. Just because the reviewer is established and successful does not immediately make them qualified to critique your work. At a conference last year I signed up for three portfolio reviews. I learned very little beyond what I already knew of my work. In fact, in regard to one of my favourite images, one reviewer said he “doesn’t get” these types of photos, while admitting that others did. Okay, then. In all fairness (and at the risk of sounding immodest) I have been practising photography for over 20 years and my work is probably “beyond” the services provided by these particular reviewers (no doubt I would find a review with the likes of Guy Tal or William Neill most illuminating). However, for those not as far along in their growth reviews can be of much use, provided the reviewer exhibits the traits outlined in Chuck Kimmerle’s blog

Relying on Ourselves

While having our work critiqued by others can have a useful and transformative impact, we must ultimately learn to rely on ourselves when it comes to evaluating our own work. We will not always have access to a reviewer’s eyes and opinions. More importantly though, who knows you and your relationship with your subject(s) better than yourself? As Guy Tal points out in his article Judging the Judges, “how can a critic know if the photographer was successful in expressing something without knowing what that something is?”. Beyond a certain point in our development outside critiques are by and large immaterial. Not everyone shares your sensibilities. Approval must come from within.

The biggest challenge with self-critique is evaluating our work with an objective eye. As stated in the David Ulrich quote at the head of this article we need to have a critical distance between ourselves and our work if we are to be able to objectively view it. We need to realize that our work comes from us, it is not of us. Linking our identity to our work leads to much pain and frustration. We must not fool ourselves, one way or the other. Personally speaking, at times I flip-flop between thinking I’m something special as an artist to believing I’m nothing more than a hack. The truth is somewhere in the middle, we must find the true perception.

Identifying our failures is critical in our growth as artists, for we often learn more from our failures than our successes. Recognising our successes is often easy, our failures, on the other hand, can be more difficult to acknowledge. We look at the flawed image hoping that in time it will somehow fix itself, or we try and convince ourselves that it’s not really that important a flaw. I know from experience the temptation to keep “almost” shots. We know deep down when a photo doesn’t cut it, as difficult as it may be to openly admit it. Perhaps it was a once-in-a-lifetime type of shot that just didn’t come out right. Or perhaps it carries so much emotional weight from the experience or what was going on in our life at the time that we don’t want to let it go. Keep them if you wish, just don’t include them in your portfolio.

As creators, we often have an emotional attachment to our work based on what we were feeling or experiencing at the time of the capture. That part is important to us, but not the viewer. We must divorce ourselves from that emotional attachment that can colour our perception of the photo. The best way to do this is to put some distance between yourself and the making of the image. Let it sit for a period of time, a day or two, perhaps even a week. When you come back some of the lustre and emotion will have worn away and you’ll be able to evaluate the image more objectively.

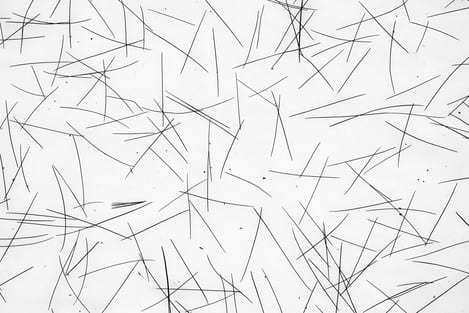

It is easy to spot technical shortcomings, or at least it should be, which is why I am not going to spend much time addressing it here. Photographers are first and foremost observers, it shouldn’t take much effort to spot such obvious mistakes ranging from the most simplistic (sensor spots, tilted horizons) to more technical (improper depth of field, processing issues, etc.). It’s the more artistic and creative qualities of a photo that are challenging to self-assess. A photo can be technically perfect and yet still not be successful. Usually, the first question I ask myself is the image interesting. I don’t concern myself with whether or not my audience will find it interesting, that is irrelevant to me. All that matters is that I find it interesting. I value simplicity in my images to a great degree, but at times simplicity can be simply boring. I then judge how original it is compared to my body of work. Is it something new and fresh or more of the same? Being self-derivative is a trap of which I am always wary.

The most important criterion, however, is does the image effectively communicate what it is you are trying to express. Step back and ask yourself what it was about the scene that moved you to make the photo. What were you trying to say? Has the composition, visual design, and processing all come together to effectively express your vision? If the answer is yes then it is a successful image, no further feedback or questioning is necessary. A sure sign of failure for me is when I find myself trying to convince myself that the image works. I want it to work, but there is that nagging voice in the back of my head that knows better. In truth, I always know better.

Learning to self-critique requires confidence in one’s own work as well as self-knowledge. We must be confident enough in our abilities and vision to not fear failure. No growth will come from playing it safe. Creativity is born from the freedom to fail. Allow yourself that freedom and embrace failure as you would your successes. Like everything else learning to critique our own work takes time and practice. Our ability to self assess grows as we grow as artists. The more confident we become in our work and the more we understand ourselves and what we are trying to convey the better we become at evaluating ourselves.