Rediscovery and Storytelling

Katharine MacDaid

Katharine MacDaid was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland and grew up in the Sultanate of Oman, America, Northern Ireland and London. After graduating with an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art, she moved back to Oman for several years to make the work, which became “Of Calling Shapes and Beckoning Shadows”, a confrontation with childhood ghosts. Since returning to the UK she has continued with a long-term project considering questions around her Irish identity, while spending time working on the book project, “The Fireweed Turns”.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

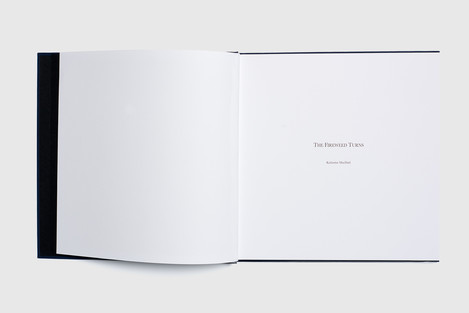

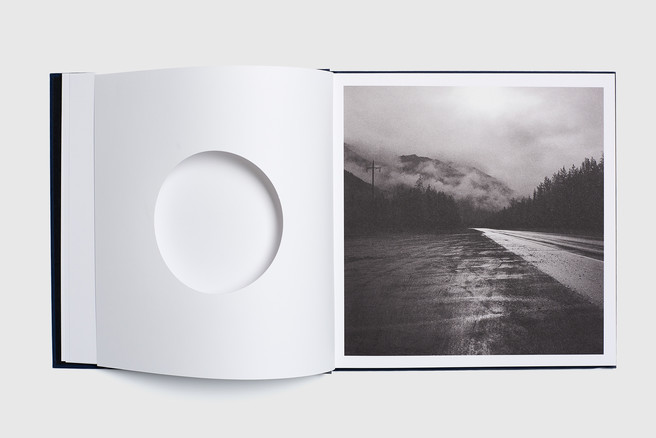

The Fireweed Turns takes place one summer in Alaska. Katharine MacDaid rented a jeep, bought a sleeping bag and a road map and set off with some half-remembered place names in a notebook. Alone in the landscape, MacDaid was both in awe and fearful of the desire that drove her.

Made to resemble a storybook, The Fireweed Turns considers the psychological power of Landscape. It is a story of shame and desire, about what is hidden and what is revealed.

Intrigued to find out more, we got in touch with Katharine to find more about her project and how she's gone about compiling the project into her first book.

What started your interest in photography and how did you come to choose it as a career?

My interest in photography started as a teenager. The chemistry teacher at school ran a photo club on a Wednesday lunchtime. We learnt how to process black and white film, I clearly remember standing alone in the science lab rocking a tank from side to side for what seemed like forever. There was only about three of us who would show up, and we would stand around Mr. Warne as he loaded a negative into the enlarger. Around the same time, my best friend and I were spending almost every Saturday night at a club in Soho, it was the late 1990’s and there was a bit of a Mod revival scene. I started taking my camera with me and shooting at the club. I printed a portfolio of images and after finishing A ‘levels, I did a foundation course at Kingston University. My final project was a series of portraits of the boys and girls from the club scene, I still have them on my website. I knew I wanted to be a photographer from then on, there was nothing else.

You graduated with an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art - How useful did you find an academic course in photography?

It was a complicated experience, it was overwhelming in a lot of ways, but it was a fundamental education for me. I was very shy when it came to my photography, not producing the work, but conceptualising what I was doing. I knew on a very instinctive level why I made work, which at that point at the RCA was a series of photographs of my parents who had just retired and moved to the middle of England but trying to formalize that feeling into a concrete explanation really troubled me. From a distance, 12 years on from graduating, I’m so glad I went through that process. I’m confident in the work I make, but I’ve also worked out what it is I use photography for. I’m not embarrassed to be straight forward in how I talk about photography. The complexity is in the work, not in the blurb.

Your early projects are mainly portraiture based, what inspired you to move to landscape photography?

In my final year of my BA at Napier University, I was making work about a group of friends in Orkney, about their ties to the island, the push and pull of belonging. I started to photograph the landscape as a metaphor for these complicated feelings. I guess it’s a very romantic approach; landscape as a representation of emotional expression. It’s still how I approach landscape photography. In Orkney, I was using a Bronica 6x4.5, which is so light and easy to wander around with and was holding it low to the ground trying to combat the huge sky. The only time I have ever sensed the curve of the earth was in Orkney, you can almost see it, the land is so flat and there’s nothing blocking your view.

Tell us about The Fireweed Turns project - how did it start?

It began because I was finding it so hard to untangle a huge project I had made in the Sultanate of Oman, and I thought by stepping away from one body of work and making another, I could work everything out. I had recently moved back to London from Oman and was teaching photography. I had a really long summer break ahead of me and decided to put my Alaska plan into action. I had been thinking about returning to the Pacific Northwest for a long time, my father still had a contact there from the days of working on Amchitka, so I got in touch with him and talked through some basic practicalities. From there it was a case of getting to Anchorage, then up to Wasilla where I rented a vehicle, bought a sleeping bag and a cold box and hit the road with a book of half-remembered place names.

You mentioned in the exhibition information "The landscape of the Pacific Northwest was rooted in my memory and imagination at a young age. When I was nine years old, my family moved from the Sultanate of Oman to America." Tell us about how this influenced your photography and the impact the American landscape had?

It was a massive shift, moving from one particular landscape to another. I had grown up with sand dunes next to my house and an arid, rocky mountain range behind my school. Then at nine years old, moving to America, to the Pacific Northwest, it was all dark forests and rain. I think the radically different landscapes probably affected my understanding of the world, the contrast of one place to another, that sense of feeling outside a place looking in because you can see it is so clearly different. And where do you belong? As a kid, the cultural landscape really influenced me too. America was much more vivid, more intense. Perhaps the major influence on me when I later learnt to use a camera was the desire, the need, to make sense of my surroundings…

"When I was a young girl my father worked on a remote island in the Aleutian Chain and would come home with stories of the men and the landscape, both strange and incredible." Did your memory of the landscape match you later experiences of it and how did these stories affect your work?

My memory of the landscape from when I was a kid was in some ways quite innocent, I had a sense of it being not entirely benign of course, but returning there on my own as a grown woman, I was discovering the landscape anew. The stories were a way of tuning in, the characters made sense once the landscape became apparent, I recognised to some extent how the landscape shaped them, or maybe I unconsciously searched them out…

"The Fireweed Turns project is a story about shame and desire, about what is hidden and what is revealed… " How did you build this narrative around the images to develop this story that has become the book.

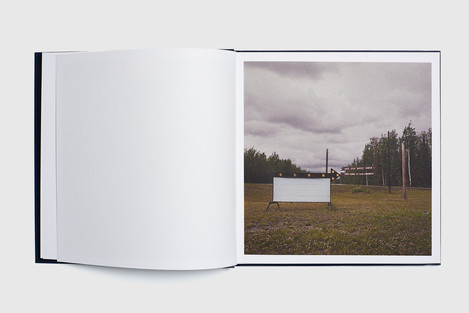

I used images in which the situation seems slightly uneasy, where there is something you can’t quite put your finger on, and gradually the more images you see, the more you realise that feeling is not letting up. There is no image that allows a happy resolution, and the terse, objective texts reinforce that. Nothing is explained, nothing is concluded or resolved. There are hints of a complete story, but no more. Every image is a question. What is it? Why is it there?

How did you go about choosing and sequencing the images to tell the story?

With help! I work really closely with my partner, the photographer Chris Harrison. The first, initial edits were done with him, choosing which images immediately worked, which could be put aside straight away, and which floated in the middle somewhere. It might be different for some photographers, but with a big project like this, I need objective input. Even when I shoot a straight forward portrait and I’m confident which one to choose from the contact sheet, I always ask Chris for a second opinion (and vice versa by the way). After the initial edit, I worked on the text for a long time. Then I worked with a very close friend, Claudia Arnold, to design the layout, which involved looking at the sequencing more closely, how the text played a role, how the rhythm of the images worked. And finally, weeks before sending the document to the printers, I changed a few images and didn’t ask anyone. I think I suddenly felt I knew the work, I knew exactly what I wanted.

What visual (and non-visual) narrative did you want to leave the reader with when you were working on this project?

A tutor of mine once said, very simply, “…one always brings their own narrative to the work”, and I really like that idea, that a viewer/reader will understand any work through their own experiences, desires, doubts, and so on, even if there is an unambiguous message. With this project, the narrative is very open for interpretation, but my aim was for an atmosphere of uneasy melancholy, a sense of the mysterious.

You choose to work with colour negative film. Can you tell us more about this, the cameras you use and how this process has affected your work? Do you think photographic film offers something distinct from digital photography?

I use a Hasselblad with a standard lens, 80mm. I have used the same camera for the last 14 years. I rely on natural light, and often only shoot a couple of frames at most for any image. I think working this way is quite specific to using film, I can’t check the pictures, I just shoot and move on. I can often sense if it’s worked or not, although I have been disappointed on occasions, as well as happily surprised… I have a feeling it might change something if I was to switch to digital, but maybe that’s overly romantic. I feel really comfortable with film, I trust my working method, but it can be an expensive process. I used to spend a lot of time printing in a colour darkroom, I would love to handprint of all my work, but now it’s much easier to have things scanned. I make a lot of hand-made books too, so I make huge amounts of digital prints to work with, just on my Epson printer.

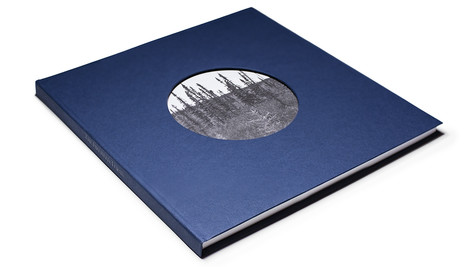

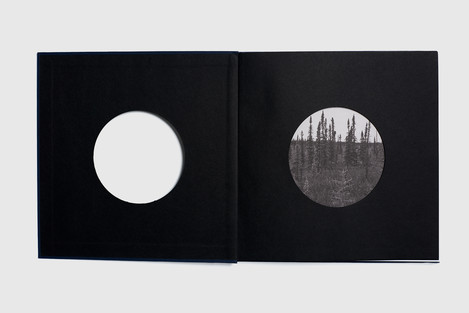

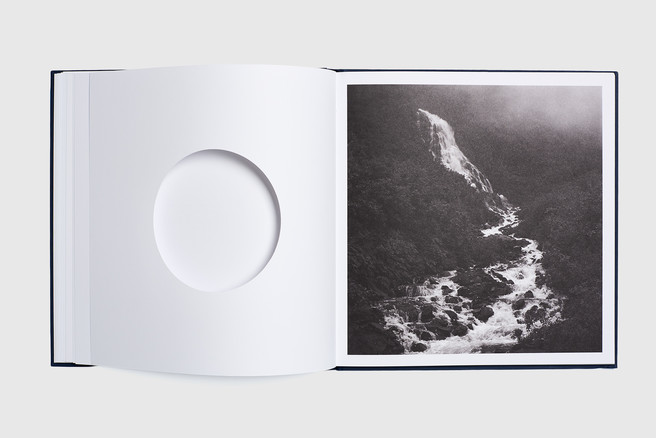

This is your first book which consists of 88-pages, including 8 circular die cuts, 18 colour photographs, 15 black & white photographs and 7 texts. How did you decide on the format of the book and binding e.g. size and paper, print type?

It was through the process of building the conceptual thrust of the work… I wanted it to have the feeling of a storybook, hence the size and square format. The die cuts, which are circles, came from thinking about old storybooks with illustrations at the start of a chapter. At first, I was using circular black and white images, but it was on showing the work to a colleague that the idea for actually cutting out a circular window began. Lots of decisions grew slowly over a long period of time. The use of slightly heavy, uncoated paper was another factor in conceptualizing the work, the ink sinks into the paper, there is a texture to the surface, it’s not so ‘photographic’…

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs from the book are and a little bit about them (please include these images in the ones you send over)

The photograph of the radar behind the little shed is one of my favourites. I remember driving past it on my way north on the Richardson Highway, seeing this looming white ball against a strange sky. I didn’t realise at the time that it’s a radar, which is what my father was building in Alaska back in the late 80’s, early 90’s…

There is a photo of a moose decoy, and I am not totally sure how it works, but I think it is a female moose used to attract males, for hunting. I like it because it looks so real. Almost everyone stops at that image and looks again, because for a moment they think I’ve photographed a real moose. When you realise it’s a flat object, it’s an unsettling feeling. I like that a lot.

And a third one - the odd little dog at the end of the book. He’s just so strange looking, like a character from a story. And he’s really looking back, it’s a portrait rather than a photo of a dog.

What sort of post-processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

I do rough scans first, I have a Nikon scanner in my studio, it’s quite basic but I can print out workprints from the scans to start the editing process. Then I have been using a Hasselblad X5 to scan the selected images, renting one for a few hours as needed. I thought they were my finals – a set of 3Fs, but then I got the images for the book Drum scanned and the difference was incredible. Tim helped me to process the drum scans in Lightroom initially, which was a huge help, but I’m much happier using Photoshop, which is where I’ll end up processing the images for print.

What is next for you? Are there other projects that you're working on?

The next place I’m interested in is Northern Ireland. I was born in Belfast, where my mother is from, my father is from Derry. I lived in Belfast for a couple of years when I was a young teenager and as a kid, we’d always spend time in Belfast and Donegal in the summer. A few years ago, while photographing on the Isle of Barra, I met a local guy. He was very reserved, yet after a drink, began to guardedly ask me about my surname. He was an anthropologist and had been doing fieldwork in Ireland. He slowly began to tell me about the family names of Inishowen, where it turns out, he had studied my surname… By the end of the evening, he was imploring me to go back and find my faeries. To return to my land and feel the soil beneath my feet, to connect to the very roots of who I am…

Katharine would like to invite you to the launch of her self-published book, The Fireweed Turns, on Thursday 14th February at The Photographer’s Gallery, London, 6pm-8pm.

You can buy The Fireweed Turns book, £40 from Katharine's website: https://www.katharinemacdaid.com/shop/the-fireweed-turns