An Interview with Toby Deveson

Toby Deveson

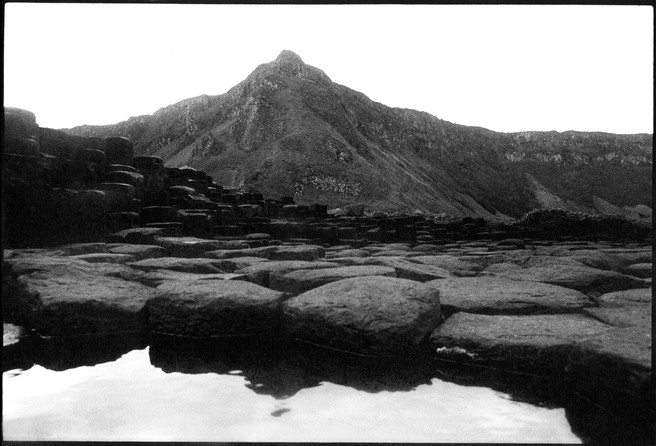

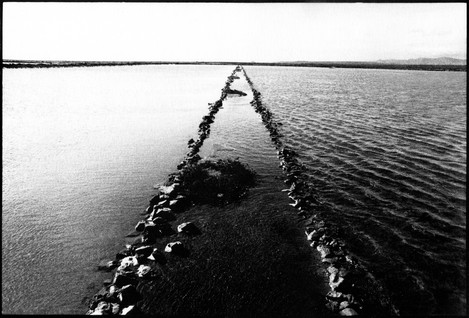

Toby has been taking – and printing – black-and-white photographs since 1989, always using an old Nikkormat and the same 24mm lens he ‘borrowed’ from his father more than 20 years ago. His images are never cropped, but are framed instinctively at the time of taking. They are then brought to life with a pinch of magic – and luck – expertly secreted within the science and chemicals of the darkroom. Whether he is photographing landscapes or people, Toby approaches his work in the same way, moving through his environment surprisingly quickly. Always watching and absorbing, constantly experimenting with framing and composition. Toby has an ability to depict the world that goes beyond the literal representation that we have come to expect from photography. His images suggest myths and magic beyond their four corners, challenging the viewer to see the world, and the medium, in a different way.

Anna McNay

Anna McNay is an art writer, editor and curator based in the woods of Hertfordshire, UK. She has considerable experience of writing catalogue essays, as well as reviews, profiles, interviews and features for online and print publications. She frequently conducts live interviews and hosts and speaks on panels at galleries and art schools.

Back in January one of our readers, Anna McNay, got in touch to see if we'd be interested in an interview with Toby Deveson. He uses his old Nikkormat and the same 24mm lens that he ‘borrowed’ from his father more than 20 years ago. He finalises each frame in-camera and doesn't crop images in the darkroom. It got me thinking about how Toby worked around these constraints in his photography and how it influenced his approach. ~ Charlotte Parkin.

Anna McNay (AM): What sparked your passion for photography?

Toby Deveson (TD): We start with the million-dollar question… Straight in there, no punches pulled!

The truth is, I don’t know. There wasn’t one single thing.

My father used to take lots of photographs, and we used to sit through the usual slide shows that so many families of my generation had to. Although I do remember there was an element of family and friends admiring his skills as a photographer, rather than the actual memories of the holidays.

The house was also filled with coffee-table books – on artists, photographers, architecture, and travel. A very eclectic selection. And, on top of that, we used to watch many films, from musicals with Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, to “Star Wars”, “Citizen Kane” and “The Deer Hunter”. All the classics. And while they may have been unfashionable films in the 80s, they were classics for a reason, and all very photographic. Essentially, I grew up appreciating all things visual.

Within those coffee-table books were collections of photographs by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Don McCullin, Bill Brandt and Ansel Adams, to name but a few. I adored them. I spent hours getting sucked into the images, seeing not only the small granular details but also the larger brushstrokes of their composition and tonal balance, as well as the narratives behind the images. It was the images, which punched me in the guts, that I loved the most.

I guess that with such a strong visual foundation to my life, from such an early age, I was able to keep building on that foundation, finding the limits of what I liked, and pushing those limits. A simple example: I loved the Beatles from a very early age – all their early tracks. It wasn’t long before I discovered their later, more psychedelic stuff, and from there, the more avant-garde, lesser-known tracks, bootlegs, jams, outtakes, and then John and Yoko’s tracks, the screaming, atonal soundscapes…

I remember clearly going into a darkroom for the first time. The father of one of my best friends at the time had a friend who had a professional darkroom, and he let us use it. We spent days taking photographs around Milan (where we lived), printing them into postcards (one at a time) and piling up about 10 different images, each printed 30 or so times, ready to set them out on a blanket on a street corner to sell. We didn’t sell many, but we had a huge amount of fun. Within weeks, I had built my first darkroom.

So, photography has always been within me and was born out of laziness and luck, passion and hard work. It came to life thanks to my parents, friends and surroundings. But without that fertile ground within me, it would have withered and died.

AM: What is it you love about landscape photography in particular?

TD: I think this question can be answered more by exploring what I didn’t like about documentary and reportage. My heroes, by the time I was a ‘fully-fledged, self-proclaimed photographer’, were Josef Koudelka, Sebastião Salgado and Mario Giacomelli. High contrast, from the soul, and loose. I knew of no landscape photographer who spoke to my soul in the same way. I liked that. I wanted to create work that was new and unique and spoke to my soul in the same that way so many powerful reportage photographers spoke to so many people around the world.

I was learning to tell photographic stories in the Romanian orphanages in the early 90s, and I felt I had to take ‘filler’ photographs, too. Empty rooms, details of discarded toys, blood smears on walls, and also the landscapes which surrounded the orphanages. Photo essays. Looking back, the landscapes were where I found peace and refuge from taking the other images.

And yet the landscapes were the images I always struggled with. I would return with scores of powerful images of people, which I loved printing and were well received by tutors (I was still at college at the time), and I quickly and easily found my voice. But my landscape images never had the same impact – that frustrated me and challenged me.

On top of that, as I faced graduating and having to start my ‘career’ as a photojournalist, I was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of chasing hardship and suffering, and the psychological justifications of photographing people and their private lives. I found myself longing for the solitude of Mother Nature and her wilderness, being drawn more and more to the challenge of finding the same voice I had found in reportage, but in landscape photography. I wanted people to be left speechless, drained and exhausted from my landscapes, not my reportage. I was feeling increasingly disillusioned with people reacting more to the stories behind documentary photography than the images themselves. Landscape photography, for me, meant having no story to hide behind, simply a good photograph. And black-and-white landscapes meant you couldn’t hide your mediocre photograph behind a glorious sunset or location. You had to produce the goods with your composition and your artistic skill. That is what I loved, and that is what I was drawn to. I recently compared the challenge to ‘winning the Booker Prize for literature with a Mills and Boons novel’ – i.e. moving from ‘serious’ documentary photography to ‘chocolate-box, cliché, shallow’ landscape photography, yet succeeding in continuing to produce work with the same power, punch and soul as before.

AM: Can you give a little background on what your first artistic passions were?

TD: I wanted to be a painter, but never quite found the passion or ability to focus on a canvas for more than a few days. Photography, for me, comes in short, sharp bursts. Taking the photos, developing the film, contact sheets, printing, framing and exhibiting. It is much easier to cope with for lazy, easily distracted people!

Thinking about the passions that shaped me before photography though, I always come back to more abstract things. Solitude. Nature. Daydreaming. Travelling. I think they qualify as artistic passions – and they certainly influenced me and have stayed with me throughout my life.

AM: You studied photography at Brighton. Did this shape your use of film and your love of the darkroom?

TD: Yes and no. I was there in the pre-digital era, or, at least, before it became a serious ‘threat’ to the status quo. So, it was only ever film. I was there the year before the photography degree started, though. I was doing a course called Visual & Performing Arts. I chose it because it incorporated music in the course. I had done my Grade 8 theory of music when I was 14 and A-Level music alongside my art. I didn’t realise that the course was essentially for the ‘Kids from Fame’ and way outside my abilities and comfort zone. But I was the only person using photography as a medium, so the small darkroom in the attic of the building was pretty much mine. And the photography tutor, John Holloway, was incredibly supportive, knowledgeable and helpful. But I was also left to my own devices, and I developed as a photographer so much thanks to the freedom this offered me.

As I said above, I went to Romania while doing my degree. There was an organisation called Creative Aid for Romania, which I joined – having cycled to Eastern Europe from Milan when I was 17 or 18, weeks after the Iron Curtain fell, I felt an affinity with Eastern Europe. Creative Aid had started in response to the Romanian Orphanages being in the news and, essentially, they travelled out twice a year, overland, to paint murals and offer what was, looking back, a basic form of art therapy in the orphanages. I went out about four times and took the opportunity to be the self-appointed photographer. Being able to return to the country and the orphanages, at this stage of my development, so many times, was such a privilege. To be able to study my photographs each time and figure out how to improve them was a crucial part of my learning curve, morally and photographically.

For my course tutors to allow me to be absent for a couple of months at a time, especially in my final year, was very generous indeed. The trust and freedom they gave me shaped me immensely, too.

AM: Your day job is as a television cameraman. How has this influenced your photography or given you access to different locations?

TD: The only real influence is in the occasional opportunity presented to me for trips. I have been lucky enough to have had jobs around the world, and occasionally it works out that I have time off after a job, so I ask for a delayed return flight. I then hire a car and go and ‘play’.

AM: Were there any key moments in your life which shaped the way in which you developed as a photographer?

TD: After my first trip to Romania, I returned with what I thought were extremely powerful images. My memories were (to put it bluntly) of dying babies with big eyes looking up from their cots, and those were the images I returned with. They were what I had seen in the papers before I left, and they were what I took. I printed them and exhibited them, thinking I was the new Salgado. But the feedback I got said otherwise. They were slated. They were called lazy clichés. I was given abuse for turning my lens on dying children. I learned an important lesson in those months. I learned that you can’t hide behind your memories, and you can’t hide behind the story and suffering of the people you are photographing. I learned that if you are going to essentially rape a person by photographing their soul and their suffering, then the very least you can do is pour your own heart and soul into what you are doing and produce work that is earth shattering. Work that is beyond what you thought you were capable of. Anything less is morally unacceptable. So I returned, again and again, and pushed myself compositionally and photographically. I made sure I photographed my real experiences, not what I thought people expected to see. I found laughter and joy and fun, and I photographed that.

AM: Who has specifically helped you in realising your photographic ambitions over the past few years?

TD: The who is easy; Carla, my partner, is my inspiration and muse. She is a journalist, writer and TV presenter, and together we have started a podcast and YouTube channel called “Metralla Rosa”, for which we interview artists, musicians, writers, dancers, creators, and thinkers in general. Interesting and inspirational (and, yes, avant-garde and alternative) people. Carla is Venezuelan (with Italian roots – so the channel is multilingual), and when she moved to the UK, more than 10 years ago, she gave up an incredibly successful TV and radio career, and eventually ended up working as an artists’ model. So not only does she inspire me on a personal and artistic level, but she adores me photographing her.

The arrival of the iPhone, however, has had a huge, yet indirect, influence on my photography. Probably more so than any individual person. My ‘photography’ will always be analogue and black and white. But, over the years, it had become oh so serious. The iPhone, like the Box Brownie in the early 20th century, has brought photography to the masses. It made it fun for me again; it made it easy. Like with my 24mm lens, I couldn’t zoom, I framed at the time of taking, but I didn’t have to worry about printing or exhibiting. I took a photograph and moved on, no pressure, no drama. I had fun with colour, I had fun with composition. The iPhone has really helped me rediscover the fun in photography – it has helped me remember why I take photographs, why I fell in love with it in the first place.

AM: Before photography, you wrote music, which you have described as ‘avant-garde, atonal and arrhythmic,’ as well as ‘jarring and jolting’1. What synergies are there between your music and photography?

Many. They share the need I have always had to push the boundaries and make things uncomfortable, but not unpleasant. I still want people to fall into and lose themselves in my photographs, but I want to challenge them as they do so. I stopped writing music at about the same time I discovered my photographic voice, but, I think, if I had continued, I would have ended up doing the same thing. Making challenging but accessible music.

It is all too easy now to gloss over art. We are bombarded continuously with visuals. Powerful imagery is drowned daily in seas of mediocrity. Aspiring photographers are learning in the public, social-media eye, and it has become harder and harder for the truly talented and ground-breaking to rise above the noise. For imagery to catch the eye and remain with someone, it needs to be different, powerful and challenging, yet welcoming and familiar at the same time. That is what I hope I do with my landscapes.

AM: How differently do you approach photographing a landscape from photographing people?

TD: The process is identical. I use an old Nikkormat and a 24mm lens. I always felt I needed to be mobile and quick as people move and surroundings change, so definitely no tripod. I didn’t crop, so I needed to frame quickly but accurately. The lens was a prime and always the same, so I knew what to expect when I looked through the viewfinder. I wanted to work within strict and familiar parameters: just me, my eye, and my feet. That hasn’t changed at all now that I photograph Mother Nature instead of people. I move quickly and document my surroundings in as many different ways and from as many different positions as possible.

AM: As you have just said, you use your old Nikkormat and the same 24mm lens you ‘borrowed’ from your father more than 20 years ago. Do you enjoy working within these constraints, and do you think it has influenced how you approach your photography?

TD: Yes, I love it! By simplifying absolutely everything about the process leading up to and after the release of the shutter, I can give everything to that single moment. I can fully immerse myself in my surroundings. My raison d’être is to create the perfect, perfectly framed image. I live for that moment where it all comes together; that split second before you release the shutter, where you have created something by the seat of your pants, instinctively. All the rest is just noise and inconvenience. I have a love-hate relationship with it. To have the familiarity – and constraints – of my lens, camera body, film and paper gives me the freedom to let myself go and have fun when it matters most.

AM: You say in the video above that the image-making process is a two-way journey: there is what is coming into the camera, but you have to have something going the other way and put yourself into the film as well (the US idea of mirrors and windows). How do you personally balance these two aspects?

TD: I have no idea! It just is. The process is something that has happened naturally and organically.

AM: ‘To not be engulfed by her [Mother Nature], and to not rely on her to provide you with a stunning image, but to work with her and create something unique from something so universal’1. How does this express itself in your work?

TD: My mantra, and my process when I work, is to try and create an image from a location that no other photographer would think to create. I strive to come away with something that is unique and can only be mine.

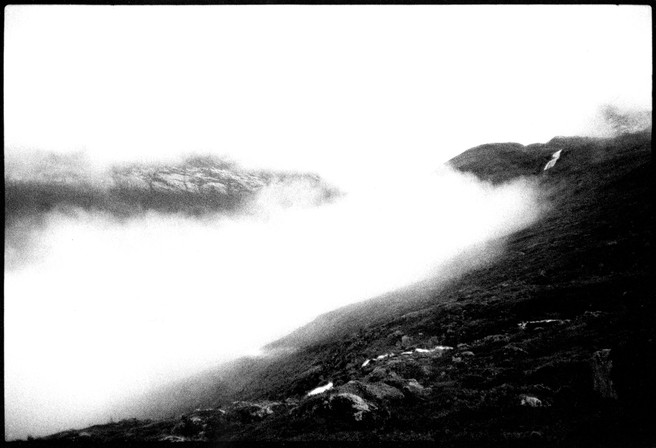

This manifests itself in my process, I guess, in the way I arrive at a location and take the obvious photographs first. The safety shots. Especially in a fast-changing situation. Disappearing mist (which disappears far faster than most people realise) or fast-moving clouds. I make sure I have these obvious, slightly more cliché images in the can first (they are cliché for a reason – more often than not, they end up being the best). Then I start pushing: going for alternative framing, experimenting, changing the balance within the frame, playing with the possibilities. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. More often than not, it doesn’t. I fail a lot more often than I succeed!

AM: Do you feel you are the sole creator of your photographs, or does the landscape, or something else, play a role?

TD: I work incredibly hard to be the creator of my photographs.

AM: Does using an analogue rather than a digital camera change the way you interact with the landscape?

TD: No. I have never known any different. If a location is particularly stunning, once I have exhausted every possibility with the film camera, I will snap some photos on my iPhone – as memories, to send to Carla, or to friends, or maybe to post on Instagram. But I am there for the moment, for myself, and for my photography. Nothing will distract from that.

AM: Your images are never cropped but are framed when you are making the image. Is this a creative or technical decision?

TD: A bit of both. The original decision was one of laziness. Cropping was such a hassle. Getting the crops in the right place and making each print identical (crop-wise) was too much work. Plus, when I found it was encroaching on the taking of the photograph when I found myself thinking: ‘This framing isn’t quite right, but I can fix it later,’ I knew I had to nip that in the bud. I haven’t cropped (an analogue) image since perhaps 1990. It has since, of course, become a creative decision!

AM: You collectively refer to your landscape photographs as “West of the Sun”. Tell us more about where this title came from.

TD: It was taken from the title of a book by one of my favourite authors: “West of the Sun, South of the Border” by Haruki Murakami2. In it, he talks of never being able to get to the west of the sun. You can never overtake the sun as it travels ever westward. The origin of this train of thought in the book came from the Siberian prisoner camps and a mental illness and breakdown, whereby prisoners would drop their tools and, overwhelmed by the endless horizons and snow, just start walking towards the sun in a daze. But, to me, it also speaks of the need to always climb the next mountain, to chase your dreams, to find that other world somewhere over the rainbow. The endless search (for me) for that perfect, elusive image.

AM: How do you go about finding locations for your images? Do you work in a project style, focusing on a specific theme, or is it more location based?

TD: Assuming I am not limited by time or money, I, first of all, choose the country (no limitations, perhaps New Zealand or Japan; if time or money are a factor, perhaps Morocco or France). I buy as many maps as possible and do a quick search for national parks in the relevant Lonely Planet guidebooks or online. Then I roughly work out how many miles I think I can travel in the time I have before my return flight, try and connect as many national parks or interesting locations as possible on the maps, and then jump in a hire car at the airport and just drive!

I stop off in a supermarket, fill the backseat with water and food that won’t go off, and then I sleep in the car. A couple of hours before dusk, I start looking for a car park or a small road I can pull over on, ideally near to somewhere I want to photograph in the morning. I really do just follow my nose and instinct. I try to let the landscape guide me, as mystic as that sounds.

AM: Tell us a bit about two or three of your favourite photographs from your book, “West of the Sun”.

TD: The book is still not finished, but so far, as much as I try to detach my memories of the images from the actual images (to ensure I don’t confuse how good the photograph is with how good my memories are), some of my favourite images are the ones that have powerful memories and emotions attached to them. But there is no real consistency as to why an image becomes a favourite. Some, I fall in love with at the time of taking; some, I discover in the darkroom; and some, I print and put to one side, only to find them taking root in my psyche and becoming firm favourites in a ninja, sneaky way.

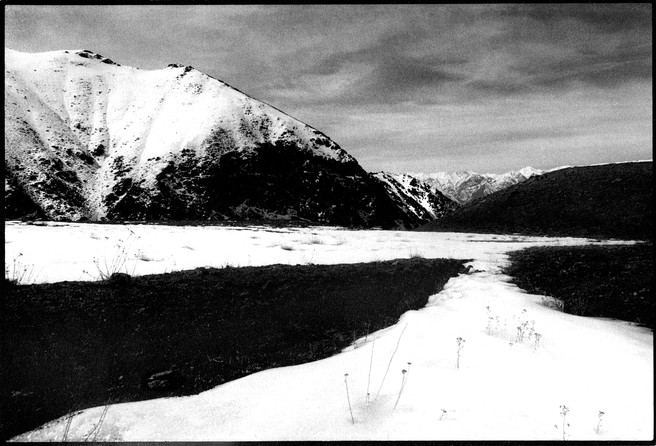

Þórisjökull, Suðurland, Iceland. August 2015

I always dreamed of going to Iceland to photograph, so to finally be there was thrilling. It took me a while to take a photograph I was pleased with, though – enough time for the worries and doubts about myself and my abilities to creep in. But then this one came along. It wasn’t the most striking location, but I found this shape and composition, which is abstract and inconclusive as far as scale goes, and I love that. I love that there is very little about it that says ‘Iceland’, with its majestic, sweeping landscapes.

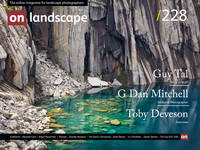

Parque Nacional Queulat, Chile. February 2018

This one was early in what was a grey, misty and dull morning. It was taken by the side of a road which was still very quiet. I was still stiff and cold from sleeping in the car, and I had been bitten to death by midges the day before. I had to stand on a small rock to get as high as possible, and I couldn’t tilt down any further because the lower bank of the river-cum-marsh would have crept into frame, so I knew the composition was going to be top heavy, yet something was telling me it would work. And it did. It is my favourite combination – an uncomfortable, weird composition, which still works perfectly. The grey drabness meant I knew I’d have to push the negative and make the mist as white as possible. The remaining land and water are so magical – I have spent hours getting lost in those shapes.

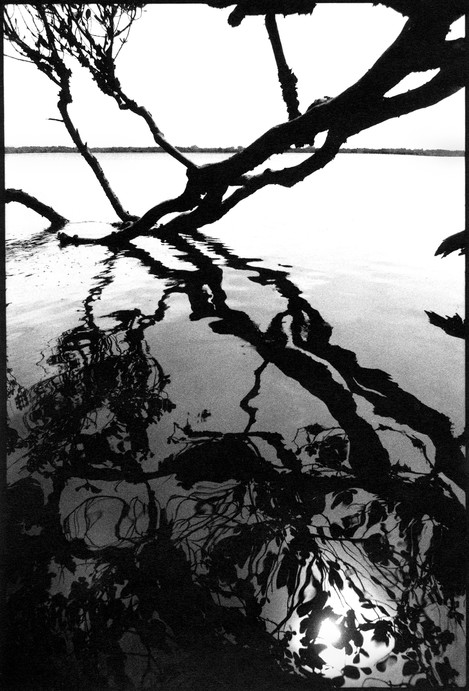

River Soča, Slovenia. August 2013

This one was taken on the side of a very busy dual carriageway. I had slammed on the brakes during the long trip back to where we were staying for our summer holidays, after a long day walking in the mountains, and left my tired and hungry kids in the car while I sprinted 50 or so metres to the end of the lay-by, to try and find a gap in the trees. I had to balance on the guard rails, feet jammed between the metal strips. I could feel the wind from passing cars blowing me off balance. I struggled to lose all the foreground (very difficult with a wide-angle lens), so had to feature one small tree bottom left. But I managed to make it work. Because the moment of taking the photograph was less than ideal, and I was by the side of a busy road, my expectations were low and my memories tainted. I almost didn’t want to like this one. I tentatively exhibited it and always felt apologetic about it. But it has slowly and consistently grown on me purely as an image.

AM: You obviously love working in the darkroom. Tell us more about your processes and how you go about printing your images.

TD: I hate working in the darkroom… I mean… I love it… Yes!

It really is a love-hate relationship. I love bringing the prints to life, but sometimes it is a struggle. I hate the slog of doing the contact sheets, especially when I return from a trip with 90-odd films. Developing the film is also a long process, as I only do two at a time (after watching someone in college use a tank with six films, getting it wrong, and ruining them all), but I also love it.

As for the actual prints, I usually knock off a few 8x10 of all the images I think I want to see. I get them about 80-90% right and move on. These are the prints I scan and use for my website. I fix what I didn’t quite get right in the darkroom, maybe darken the sky a bit or lighten something slightly in Photoshop. I usually give them a touch more contrast than the physical prints have, as there is nothing worse than a dull, grey print on the screen. I really don’t think a computer screen, no matter how good the scan, can show the subtleties of a darkroom print in the flesh, so I find I have to compensate by giving my ‘screen’ prints a bit more oomph.

Then, I eventually move on to my exhibition or portfolio prints. I tend to live with my 8x10s for a few months and make sure I still think they are good enough over time. To get a print 95-100% right, or as close to perfect as possible, can take anything between two to 10 attempts. But it usually averages out to about three. I tend to do about two to four prints a day. Then I touch them up and frame them or put them in the folio. I print to order, as far as sales go. I rarely print more than I need.

AM: You have a consistent contrasty ‘look’ to your prints. Do you have a good idea of how your images will appear in print while making them?

TD: I tend to use very heavy negatives, and that typically leads to high contrast. I generally have no idea how or why I have achieved the results I have, but I like it like that…

AM: What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

Right now, I see no imminent changes. I will still photograph people when the opportunities arise, but I will put all my heart and soul into adding to my landscapes, exhibiting, selling, and working towards a book which, at the moment, I intend to self-publish. I would like to find a gallery to represent me so I can increase my sales, abroad as well as in the UK, but I am also very happy with the way things are at the moment.

References

1http://art-corpus.blogspot.com/2020/12/toby-deveson-embracing-most-sacred.html