Embracing uncertainty in landscape photography

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

Serendipity: An unplanned fortunate discovery. The first noted use of "serendipity" in the English language was by Horace Walpole on 28 January 1754. In a letter he wrote to his friend Horace Mann, Walpole explained an unexpected discovery he had made by reference to a Persian fairy tale, The Three Princes of Serendip. The princes, he told his correspondent, were "always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of." The name comes from Serendip, an old name for Sri Lanka (Ceylon)1

Landscape photography is often a result of good planning, helped by online tools such as PhotoPills and 3D Google Earth (and just occasionally, perhaps, by pictures taken by others and posted on Instagram or seen in books, though we might be reluctant to admit that…). It is now possible to know where to go to get a promising viewpoint with the sun or moon or Milky Way in just the right position for that key shot. The online weather forecast might also help in knowing what conditions to expect, and whether there might be clouds to light up in the sky as the sun comes up (or goes down), an inversion that will produce a layer of cloud in the valley bottoms, or a clear sky with a new moon to reveal the Milky Way. And all before leaving home.

But we also all know that such planning does not always work out. The sun goes behind a cloud on the horizon just as it looks set to light up those clouds; the weather forecast got it completely wrong; there are too many aeroplane contrails crisscrossing the sky or the sky is totally clear and does not provide any interest; or you arrive to find that there are already 50 photographers taking all the best places, lined up tripod to tripod. I still remember being really shocked the first (and last) time that happened to me, 25 years ago now before sunrise at Mesa Arch2.

When things work out, the planning can be highly satisfying, especially if the research involved has revealed some new location that will be worth going back to again and again. But this article is about another approach that allows for the uncertain, the unpredicted, the unexpected, the serendipitous. It is an approach that, for me, was partly instigated by that experience at Mesa Arch. It has some advantages in that the resulting images may be found anywhere and are unlikely to have been seen or posted by others. Even more important, however, is the nature of the process required, the way that the search for the unpredicted requires concentration on the possibilities wherever you are. I would suggest that a fine example of embracing the uncertain is Mark Littlejohn’s winning LPOTY photograph “A beginning and an end, Glencoe” from 2014 (still my favourite of all the LPOTY winners)4. This was a serendipitous opportunity, but clearly, Mark had to be primed and ready to see the potential for such an arresting image. I have also driven through Glencoe when the weather has been down, the light was poor, and the waterfalls were streaming off the hillside. In my case, I was concentrating so much on driving through the lashing rain that any thoughts of possibilities were only a vague feeling that I might be missing something interestingly hydrological!

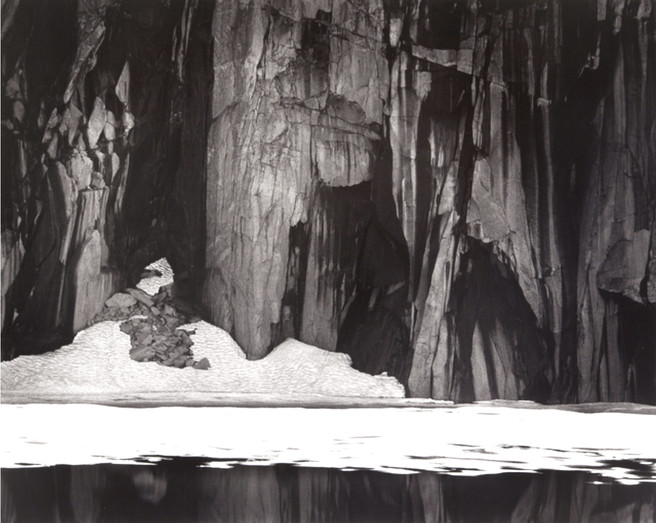

But I do have some personal examples of unanticipated images. One that was quite important to me is from Yosemite. With an interest in the history of landscape photography, I have been fortunate enough to visit Yosemite several times (though on the last occasion in a December when I had hoped that there might be some snow, the downside of the uncertain raised its head in that we could not get into the park because of snowstorms and drifts). I have some nice shots from earlier visits, though to my regret I have never been able to stay long enough to walk up into the backcountry of the Sierras, where perhaps my favourite image by Ansel Adams was taken5. There is an element of serendipity in that photograph, too. The snow patch at the base of the cliffs, and the way the scree is revealed, as he passed on that day in 1932, are all important to the image.

Those “nice” shots of mine do not begin to compare to some of the classic landscape photographs of Yosemite, not only by Ansel Adams, but also by Carleton Watkins, Charlie Cramer, John Sexton, and many others6. That can, of course, provoke disappointment when the results are not quite as interesting as we had hoped during the limited time that we could be there (more so if that arises after we have had to wait until a film is developed and printed after leaving a location). The result is that the Yosemite shot that I am most happy with was a result of looking a little more closely, and a little differently, on a trip one autumn after the first frosts had started to turn the colours of the vegetation. It is lacking a little in grandeur, perhaps, but evokes some of the granitic essence of being above the valley.

Uncertainty is much discussed in science and philosophy. Various types of uncertainty are distinguished, from ontological uncertainties (does something exist?) to epistemic uncertainties (arising from a lack of knowledge7) to aleatory uncertainties (appearing as if randomly variable8). We might encounter all of these in our photographic lives, though we generally do not have to worry too much about the first if we are prepared to accept that we exist and that the landscapes we are interested in photographing also exist (at least in the Matrix!!). Epistemic and aleatory uncertainties are often handled these days by the use of Bayesian methods9. Bayes equation is a way of combining prior beliefs in possible outcomes with evidence for those outcomes expressed as some form of likelihood measure. We can draw a qualitative analogy with Bayes when combining the planning that gives rise to our prior expectations, with the uncertainties of actually arriving in a place and updating our expectations on the basis of the evidence we find at the time. Bayes methods are often used adaptively for evaluating risks in such a way, but a fundamental issue is how we formulate our (subjective in this case) likelihoods for potential images as outcomes.

This will be critically affected by our past experience and, in respect of photographs, the way we train our eye (as clearly was the case of Frozen Lake and Cliffs and Mark Littlejohn’s Glencoe image). There will always be uncertainty relative to our prior expectations, the question is how do we react in embracing that uncertainty to reveal possibilities? Are we just disappointed and give up if our prior expectations are not met, or do we update to consider other possibilities? With the right mindset, there can be real pleasure in doing the latter.

The pleasure is in the process because as photographers we can search to make selections of both framing and camera controls to create what we hope might be interesting. It is all about of having the facility with a camera to make choices and selections from all the potential compositions that are encountered. And even if the prior expectation of the grand landscape might not prove to be a suitable composition at a particular place and time, there will certainly be points of detail that might be worth hunting for (as with my Yosemite image) thereby overcoming any potential disappointments relative to our prior expectations. The process then involves looking more intently.

Observing in such a way can also carry over to times when you are not carrying a camera (in the unlikely event that might happen, of course). Dorothea Lange has been cited in various previous articles in On Landscape but her best-known quotation seems particularly apt here:

The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera

Dorothea Lange had more to say about planning, uncertainty and the search for images.

To know ahead of time what you're looking for means you're then only photographing your own preconceptions, which is very limiting, and often false.

The best way to go into an unknown territory is to go in ignorant, ignorant as possible, with your mind wide open, as wide open as possible and not having to meet anyone else's requirement but your own.

Photographers stop photographing a subject too soon before they have exhausted the possibilities.

There are also comments from other photographers about embracing the uncertain and being open to the possibilities:

One thing I’ve learned over the years is that, no matter my location, plans or expectations, I ALWAYS find subjects in nature that thrill me and inspire me to photograph!William Neill

When you are looking to find photographs... open up your mind and be still with yourself. The photographs will find you.Paul Caponigro

Sometimes the most interesting visual phenomena occur when you least expect it. Other times, you think you’re getting something amazing and the photographs turn out to be boring and predictable. So I think that’s why, a long time ago, I consciously tried to let go of artist’s angst, and instead just hope for the best and enjoy it. I love the journey as much as the destination. If I wasn’t a photographer, I’d still be a traveller.Michael Kenna

In thinking about this subject within my own personal experience, I was drawn to some examples that come from a spell I spent in Sweden.

So again, my eye was attracted by points of detail in the landscape, at the wonderful mosses and lichens and flowers and boulders that can be found almost everywhere but which requires that focused serendipitous search for the framing of an image that works. My search for the unexpected resulted in a number of images that I still find satisfying (to me at least). At this time, I was using a Mamiya 6MF medium format (6x6) film camera. All of the images presented here were taken with the Mamiya. Some other water pictures taken in Sweden at the same time, including on that Midsummer trip to the north, can be found in the recent book “The Still Dynamic”10. These images are examples where to quote Dorothea Lange again:

While there is perhaps a province in which the photograph can tell us nothing more than what we see with our own eyes, there is another in which it proves to us how little our eyes permit us to see.

We have to deal with uncertainty and risk in many aspects of life. We do so more or less successfully, depending on how we are able to manage our prior expectations and our vulnerability to the unexpected (especially in an age of Covid). In photography, we can at least embrace the process of actively looking for the unexpected. That will give opportunities to expand the range of possibilities that our eyes permit us to see. It can also provide the additional satisfaction of then being able to study the detail in the still image, detail that might otherwise be overlooked. It is a process that is, perhaps, best viewed as a type of lifelong learning; developing the ability to be able to discover a subject to thrill wherever we might be, and to enjoy the journey as much as the final destination of the images that result.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serendipity

- By coincidence, David Ward also refers to the overabundance of photographers at Mesa Arch and elsewhere in his recent article on Acquisitions and Inquisitions in Issue No. 235, see https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/07/david-ward-acquisitions-inquisitions/

- See the On Landscape articles by Joe Cornish in Issue 180 at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/03/a-question-of-responsibility/ and by Sarah Marino in Issue 197 at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/12/7-principles-reduce-impact-nature-photography-wild-places/

- See for example, https://www.dpreview.com/articles/3186932573/uk-landscape-photographer-of-the-year-winners-announced

- It was reading Tim’s interview with G. Dan Mitchell in On Landscape Issue No. 228 (https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/04/g-dan-mitchell/) who did get to the lake that prompted this article. I still have a framed reproduction print of Frozen Lake and Cliffs, Sierra Nevada, 1932, on the wall. The story of the image can be found at https://www.anseladams.com/frozen-lake-and-cliffs-sierra-nevada/ . I will have to be satisfied with a reproduction print; reported prices for a silver gelatin print at auction are the same order as a Fuji GFX100S/Hasselblad 907X and lens.

- And I have, in previous articles, suggested that more versions of such classic shots are really redundant (see https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2020/06/landscape-and-the-philosophers-of-photography/ in Issue 208 and https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/03/devils-dictionary-photography/ in issue 228) though many photographers clearly disagree.

- From the Greek word for knowledge

- From the Latin word for dice or a game of chance.

- These are named after the Reverend Thomas Bayes (1701-1761), a Fellow of the Royal Society (though he never published much in his lifetime). His paper "An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances” was discovered amongst his effects after his death by his friend Richard Price who arranged for it to be read at the Royal Society. The paper appeared in the Transactions of the Royal Society in 1763. The paper presents a particular case of combining prior odds of a particular outcome with degrees of evidence for that outcome. A more general probability formulation of Bayes equation was developed independently by Jean-Pierre Laplace in France in 1774.

- “The Still Dynamic” was published by the Mallerstang Magic Press in a limited edition of 100 signed copies that have now almost sold out. A PDF version of the book can be downloaded from https://www.mallerstangmagic.co.uk for £10, all of which will be donated to the charity WaterAid. Paul Kenny has provided a Foreword. The book includes two serendipitous images taken with a small Olympus TG-5 near Ballachulish while on a Large Format workshop with Tim Parkin and Richard Childs (ironic that!!).