How to Build a Photo Tour

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

I love making my workshop participants uncomfortable.

You might think that I mistakenly believe that I’m working in “hostility” rather than hospitality. But I don’t mean uncomfortable in a rickety bed, no hot water, damp room, cold and unappetising food kind of way. No, I always go out of my way to make sure my clients’ creature comforts are amply catered for. Instead, I strive to take them out of their creative comfort zone to provide photographic challenges at unexpected, often anonymous, locations.

I passionately believe that we only thrive and grow artistically if we’re challenged. It is, therefore, important that I don’t always provide the easy option (here’s the prescribed view, just stop down to f13 and shoot!), as this leaves little room for growth and learning. I have on occasion seen other workshop leaders take this approach but whilst participants may initially be happy with a “good capture”, they are unlikely to make images that satisfy them in the longer term.

My intention to challenge has a profound effect on how I plan and execute photographic tours and workshops.

Let’s imagine for a moment that you’ve booked a trip to Namibia… You’re at home, packing; perhaps it’s your first time in Africa. You’re nervous and excited at the same time. You’re investing time, our most precious resource. This is going to be great! Unless, unless… What if you don’t get to see and photograph certain places and things (because seeing doesn’t count if you don’t capture it in an image!)? You’ve seen images of these sights/sites on social media and websites. They look amazing! You want a little piece of that for yourself. In your head, you’ve built a wish list, and you’re expecting me to fulfil it. To a certain extent, I’m happy to play the role of your personal Santa. But I am more interested in exceeding, not just meeting, your creative expectations.

I wonder if the tendency for preconception is worse for landscape photographers. As avid consumers of imagery, are we more likely to be led astray by the great views? Or does our critical view of photography help us to sort the fantastical from the real? I know that my instinct is always to look beyond the obvious, to search for a different angle, both literally and metaphorically. But there’s a sense of the clock ticking on a trip which can create performance pressure on participants. There’s also the peer pressure of watching other participants make images and struggling to find one yourself. Might this narrow their outlook?

I once had a workshop attendee in Arctic Norway who arrived with forty A4 images, downloaded from the internet, to show me what he wanted to shoot. He (of course, it was a “he”!) saw the landscape as a resource. He was a consumer, choosing products from the online catalogue, buying what he wanted rather than looking for what he needed. He expected everything “in store” to be as advertised on Google image search.

Photographs are divorced from all sensory inputs apart from a narrow visual selection. A photograph of the Lofotens cannot convey the smell of the sea, the seabirds’ cries, and how the winter breeze feels like a knife on your skin. His A4 sheets didn’t account for any of these things.

I took him to a location he particularly wanted to shoot where a river meandered across a grass covered plain toward the sea and distant mountains. Except in February, the meandering river was hidden under a metre and a half of snow. Despite the new opportunities in front of him, he was disappointed.

Many years ago, Joe Cornish and I were running a tour in Yosemite. For the first few days, we had the clear blue weather typical of the Sierras at that time of year. Rather than shooting the big vistas, Joe and I took the group to locations where more intimate landscape images were available. One client got quite upset because we weren’t concentrating on capturing the grandeur of the Valley. He expected that it would always look like Ansel Adams’ “Clearing Winter Storm”.

Ansel worked in Yosemite for eight decades, living there for a large proportion of that time, and only made one image like that. The participant had become so focussed on his expectation that he couldn’t see other possibilities. As American photographer, Berenice Abbot pointed out, “If we travel with expectation we make expected photographs”. They say travel broadens the mind, but only if we remain open to all the possibilities. Otherwise, travel does nothing more than confirm our tunnel vision.

Images on the Net behave like Richard Dawkin’s memes, infectious ideas that can lead us astray. This addictive quality is one of the preconditions for the creation of a honeypot photographic location. As landscape photographers, we can find it all too easy to unconsciously imitate another’s composition of a well-known location – I know that I have been guilty of this in the past.

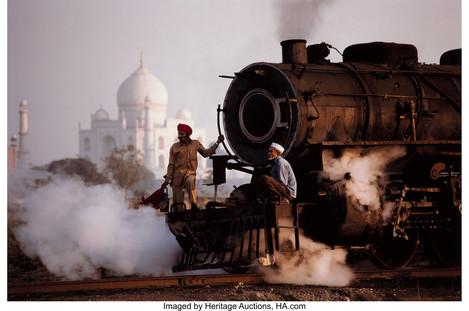

Let’s compare these two images of a slightly famous building in India:

This is beautiful, but how could it not be? It doesn’t move our perception of the Taj Mahal beyond what we already know. Simply holding up a photocopier to the world cannot change our outlook. That the building is beautiful isn’t a revelation. The photographer has simply illustrated what resides in the architecture.

Steve McCurry’s image, in contrast, changes the way we perceive the Taj. It’s no longer an isolated archetype for architectural perfection but rather a building within a wider context. By including figures and contrasting the steam train with the mausoleum (two anachronistic artefacts), we are forced to consider a wider perspective beyond the accepted cliché. We find out that - contrary to our expectations - bustling, noisy, chaotic everyday life goes on all around the ordered, symmetrical, hallowed, tranquil and perfect structure. The mythical façade is torn down.

The same idea can be applied to iconic landscapes. Let’s return to you as one of the attendees on my Namibia trip…

There’s a faint chill in the still pre-dawn air as you climb into the 4x4 for the 60km drive into the oldest desert on the planet. Soft light falls across high dunes as you begin the final leg, walking across the cool sand. Reaching the top of a low rise, you look down on the baked, white bed of a long dead lake. Its surface seems to glow. Dotted across it are the evocative, darkly skeletal remains of camelthorn trees. Towering deep-orange dunes enclose the bowl and as you watch, the first rays of dawn kiss the slopes to your right. This is your first experience of Deadvlei.

I am lucky enough to have been there close to twenty times. It never disappoints. Deadvlei is on most people’s list as a Namibia ‘must see’. I don’t disagree. It would be almost impossible to design a photo tour of Namibia and leave this hauntingly beautiful place out of the itinerary.

Unfortunately, a particular prescription for how to make images here has become dominant. But, as with all photographs, views of this place lie by omission. The myriad possible images are collapsed into a small subset, and the ‘must see’ has become characterised by a single perspective. Here are the first few rows of thousands of similar images of Deadvlei on Google.

The ‘standard view’ stresses the separation of the trees, portraying them as characters straggling across an alien desert landscape. There’s nothing wrong with that approach. For me, it evokes the primordial, desiccation, heat, a struggle, death, and persistence. You may have different interpretations; luckily, other connotations are always available!

It’s a place that seems tailor made for panoramas, and I too, made a photo in that vein.

When I made this image, a sea fret had drifted 50km across the desert from the Atlantic, filling the bowl in the dunes with lucent vapour. This is a relatively rare event, but in all other respects, this image presents a fairly typical perspective. By the way, just to prove that I, too make mistakes, this image was made on a point and shoot that I had failed to notice was in low quality jpeg mode. It was only when I loaded the image onto Lightroom that I realised my mistake. Blog sharp, but it would never make a metre wide print. Doh! Every day is a school day!

This location and view are iconic, which is partly why I chose it as the “cover” for the tour description on my website. However, I am always keen to explore alternative angles and the different moods that they might engender.

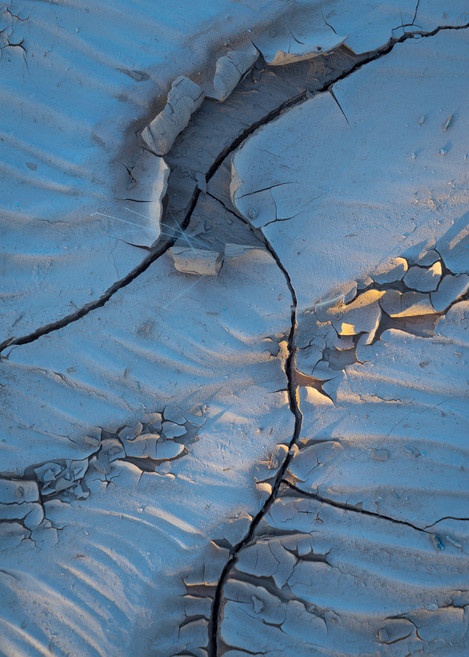

In the ‘standard view,’ the trees are silhouetted players sharing equal billing with a spectacular stage. I wanted to make the trees the main focus, showing the sand blasted lines and contortion of the trunks and branches in greater detail. Using a medium telephoto, I compressed the perspective and excluded the wider landscape. This significantly changes the emphasis and interpretation. I also wanted to highlight the extraordinary quality of the dawn light, rather than the full sun seen in most of the images. For me, one of the wonders of Deadvlei is the way that the trees and pan are lit with borrowed light. As light sweeps across the clay, it bounces off the surface, filling the shadowed trees with a beautiful soft glow. By contrast, the shadowed surface, lit only by the sky, is a deep blue.

It's important for me that the clients understand the trees’ story. Understanding why a place is the way it is - what geological forces shaped it and what life (or death) there is like - can guide how best to photograph that place. It helps the photographer decide which elements to emphasise and which to play down.

The camel thorn trees at Deadvlei lived for hundreds of years along the course of an ephemeral river, hence the straggling line. For a few days every year, seasonal rains on the distant Naukluft mountain range cause water to flow deep into the desert. The watercourse meanders across a broad plain, holding the dunes at bay and pushing 60km into the restless sands. Big Daddy (at 300m, one of Namibia’s largest dunes) stands just to the southeast of Deadvlei. The dune system is constantly but slowly on the move. Over time the sands cut off the river’s flow. From that point, the trees were doomed. They first grew here about 1,600 years ago and have been dead for hundreds of years. The region’s extreme aridity has preserved their skeletal remains as monuments to a past oasis.

There’s always much more to a location than the ‘standard’ images convey. So, I always encourage participants to see (and photograph) things from different angles, both metaphorically and literally.

There is, necessarily, always a gap between how people perceive a place or country before they visit and the reality of being there. One of my tasks is to try and bridge this reality gap for my groups. I do this by providing a lot of background information (e.g., ecology, geology, history and politics) to help them interpret what they are seeing. I believe this is much more beneficial to their photography than looking at example images on the Net. I personally find the background information essential when planning an itinerary like this. Obviously, I need to acquire an in-depth knowledge of the country before I can pass it on to the group. Gathering that knowledge takes time but it’s a worthwhile investment.

I first visited Namibia in 2008, when I worked for Light & Land, and was immediately smitten by its austere beauty. I have returned as often as I can since, and its allure is undiminished.

I’m ashamed to say that in the first year, I was as green as most of the clients! Fake it ‘til you make it is quite a common outlook for operators in the photo tour and workshop business. It’s not an attitude I have ever felt comfortable with.

After that initial tour, I set about trying to find out as much as I could about many different aspects of the country. There’s a lot to learn: Namibia is a vast country, almost 1/3 as big again as France, with one of the lowest population densities in the world. It has a fascinating history of human occupation, from the San through to the German colonial era. In the early days of my research, the local ground operators, Ultimate Safaris, were a key resource. I also garnered a lot of information from my partner, Saskia, who lived and worked in Namibia as a guide and safari company manager for over eight years. Reading up on a country using books and online resources can get you quite a long way, but ultimately there’s no substitute for first-hand experience. From 2016 to ’18, Saskia and I worked together running an eco-lodge in neighbouring Botswana. We spent a couple of our month-long leave cycles exploring the kind of places in Namibia that you can only reach in a decent 4x4 and where you don’t see another soul for days at a time.

All of these sources helped me to build a better model for a tour. The itinerary needed to include some of the better-known sights. In a way, it would be great to turn our backs on them completely, but experience has shown that clients want at least some of the ‘must haves’, and who can blame them if they’ve never been there before? The trick is to persuade them to make different images. If I was going to provide a truly novel and creative experience, I needed future tours to concentrate on the “unknown” parts of the country. (Of course, we’re not really discovering anything new as far as Namibians are concerned!) Most photo tours stick to the southern half of the country, where the dunes are at their most spectacular. They ignore the vast, rugged landscape to the north, areas such as Damaraland (typified by displays of colourful geology, magnificent tabletop mountains and bizarre looking vegetation) or Kaokoland, sparsely populated even by Namibian standards.

An obvious way to give people a different perspective is to take them to anonymous places for which they have no expectations. It’s easier to see something with the eyes of a child if it truly is the first time you see it. Even then, it takes time to tune in and see beyond the obvious, time to stare until the subject reveals itself. Rather than rushing from one set-piece photo opportunity to another, I give people the time to explore.

I set the scene for them when we arrive at a location and allow them time to commune so that they can develop their own response rather than apply an outside formula found on the Net.

You need time to notice sunlight skim across the bed of an ephemeral river, kissing the relics of the last water to flow this way…

Time to see the last light on quiver tree bark…

Time to trace the swirling pattern of a desert lily’s leaves…

Time to find chocolate-coloured curls of mud…

Time to appreciate all of these and to find ways to photograph them.

One of the best things I can give participants is the time and space to be uncomfortable… so that they can be individually creative.

If the article above piques your interest, I believe David has one or two spaces left for the workshop at the end of January, you can find out more here. Thanks David!

- White Chestnut

- Clearing Winter Storm

- The Taj At Dawn

- Steve Mccurry Taj Mahal & Train

- Deadvlei Misty

- Deadvlei, Camelthorn Trees

- Deadvlei, First Light

- Burning Bush, Hoarusib Oasis

- Camping With The Old Lady

- Damaraland Dawn

- Ephemeral Riverbed

- Quiver Tree Bark Last Light

- Karoo Lily

- Mud Curls

- Palm Trunk