Featured Photographer

Mary Frances

Mary is a UK based artist and writer working mainly with photographs, found materials, cut-up texts, and collage. Her recent work has been published by Metambesen, Penteract Press, Ice Floe Press, and Intergraphia, and has featured in a variety of collaborative projects, journals, and zines.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

All you really need to photograph is curiosity and any camera. That’s not to diminish in any way those who choose to invest in bigger and better, but it’s easy to get hung up on both the equipment and the digital darkroom. The most important component is the person behind the camera.

In this issue, we feature Mary Frances, a collector of treasure, whether it be potential collage materials or miniature and ephemeral landscapes that she finds in the streets that she wanders. We’ve often talked to photographers whose route into photography was time spent in the outdoors, but here her photographs were initially taken for use in her art projects. As we know, once you look through a viewfinder, resistance is useless. I’ll let Mary explain.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself – where you grew up, what your early interests were, and what you went on to do?

I grew up in busy south London. I think that as a child, I was quiet and wide-eyed, watching, listening, wandering, imagining, and very drawn to things that I found beautiful and strange. I learned to read very early, and my favourite stories were about children who found magical things close to home - the key to the hidden garden, a forgotten map in a cellar. I loved those stories, looking down as I walked, picking up buttons and bottle tops, pigeon feathers and silver paper from cigarette packets - small treasures to take home and turn into imaginary stories.

My grandfather introduced me to scrapbooking. He found some beautiful old ledgers put out for rubbish collection near his workplace, and he gave them to me with some old postcards and Christmas cards, a few photos, a pair of blunt-edged scissors, and a pot of homemade glue.

I enjoyed art at school and had a top grade for O level (now GCSE), but when it came to A level, the art teacher told me I wasn’t eligible because I wouldn’t be able to limit it again to life drawing, still life, and theory - there would have to be a painting, and my painting was ‘lousy’. One of my other A level choices disappeared, too, as there was no teacher available to lead it, so I left school and started a long career in care and public services.

A year later, I joined an evening life drawing class, and the man at the next easel told me about a new painting group being set up. I told him I couldn’t paint at all, and his reply was, ‘if you can draw like that, you can paint’. The following week, he brought me a beautiful box of pastels and told me to start drawing with them. I did, and it soon led to painting, and I was quite stunned. It took me a while to forgive the teacher who had dismissed me, but even so, I was relieved to have finished with school, and I do think it was better for me to work with and for other people in very practical ways. I’ve no regrets, and most of the time, I have been able to make space for art.

Before we talk about photography, I’d like to ask you about art more broadly. Your first visits to galleries and museums had quite a profound effect upon you?

I was about 8 or 9 years old when my brother took me on a bus to visit the very new Commonwealth Institute museum, and in their gallery, I found Whistler’s nocturnes. I was mesmerised by them. I don’t know how long I was there, but the attendant eventually tapped my shoulder to tell me that they were closing. When I had the chance to go back, I ran straight to the gallery, but the Whistlers were gone, and the attendant told me about how touring exhibitions moved around the world while I quietly cried.

You still find exhibitions immersive – you’ve referred to it as a kind of falling in love?

Yes, I do remember that comment about falling in love! Sometimes I just want to stay with the work and find it impossible to leave. A few years ago, after the first Covid lockdown, some galleries posted floor plans of how people would move around in the future to avoid infection. They had social distance stickers on the floor and just one space directly in front of each picture. Friends sent me images of the plans, predicting the absolute chaos I would cause as all movement ran to a standstill because I hadn’t finished looking at each picture and wouldn’t move on. In case any readers are wondering, the shows that would lead to the whole place having to be shut down until I was forcibly escorted out would be Cy Twombly, Helen Frankenthaler, Anselm Kiefer, and Sarah Sze.

How did you first encounter photography and begin to make images, and at what point did it become a creative escape or outlet?

I have enjoyed photography books and exhibitions over the years, but I only got a camera myself about 12 years ago. At that time, I had moved back to making collage work and still a wide-eyed wanderer, I thought that I might be able to use some of the colours and textures and oddities that I noticed and enjoyed in my work. So I bought a very small camera that fitted in the palm of my hand, and I started to catch things that interested or surprised me, gathering an ever-increasing supply of images to use in any way - as backdrops for collages, as unusual surfaces to draw on, and as inspirations for writing and poetry. The simplicity and speed of my click-and-go way of working means that taking photos is integrated into my everyday life now.

Given my naive use of the camera, I have never described myself as a photographer. It is still on the factory settings it came with, simply because I liked the results. Soon after starting out, I joined Twitter and loved the range of photos posted there - from professional artists showing their latest work for sale to people sharing the flowers in their garden with a phone camera and all enjoying each other's work. So I began to post my little fragments. I’m delighted that so many people find and enjoy them, and I’m grateful for the extraordinary support and generosity from many brilliant photographers - something I would never have expected.

Who (photographers, artists or individuals) or what has most inspired you or driven you forward in your own development as a photographer?

That’s such an interesting question, Michela. I think that it is mostly the ‘what’ rather than the ‘who’. One of the main challenges of art, for me, has always been how and where to begin - the fierce demand of the blank canvas, the ball of clay, the empty page. I find photography quite different in the simple way that I use it because the starting point is very clear. I’ve spotted something, and so inspiration comes towards me rather than my generating it. Something catches my eye, however small or vague, and the challenge is what to make of it.

Even so, the wide range of alternative photo and film styles and methods do inspire me, not because I’ve tried most of them, at least not yet, but because they have shown me how much freedom and experimentation are possible. I remember particularly the thrill of finding Wim Wenders’ casual and speedy Polaroid photos, the make-believe worlds of Tim Walker’s fashion photography, and the accidentally ruined film that appears in Bill Morrison’s ‘Dawson City: Frozen Time’. They sparked my imagination and confirmed my sense that there are always very many ways of looking at anything.

More recently, and closer to home, I am constantly amazed by the work of photographers I have met online. For example, the wonders of Paul Kenny’s extraordinary ‘Sea Works’; Sarah Darke’s camera-free lumen experiments; David Foster’s dreamy and mysterious double exposures; Richard Earney’s ‘Warped Topographies’, like stage sets for future fairy tales; and the close-to-home work of the ‘Inside the Outside’ collective. The variety and beauty, and strangeness of what they are doing does inspire me and have changed my sense of what photography can do.

There are many worlds available to us if we choose to look. Did anything in particular prompt you to take an interest in the tiny fragments in which you find your landscapes?

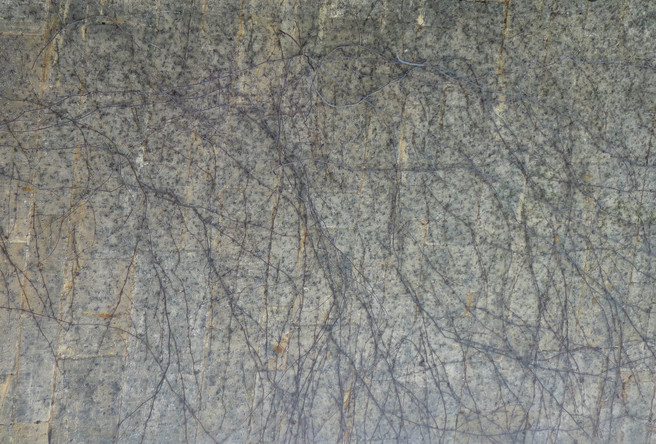

As soon as I started to look through the eye of a camera, I discovered imaginary landscapes at the edges of walls and buildings. The weathering of the stone and the silent work of lichen, insects, and weather often made them look like paintings. For a long time, I didn’t show or post them anywhere, partly because they were very tiny and partly because I doubted other people would see them as I did. I had noticed photos posted online described as ‘a cloud that looks like a bird’ or ‘a face appearing in a hedge’, and I could never see or understand them, so I thought that my tiny landscapes were just my particular and perhaps peculiar way of looking. Then one evening a few years ago, around Christmas time and after several glasses of mulled wine, I posted a little collection online and was amazed that so many people liked them and replied with their ideas of where these places might be and what they imagined about them.

For me, the ‘landscape’ images do hold a kind of magic - they are there and not there. We can see that they are fragments of walls, fences or bins, and, at the same time, we see another place - a fantasy world or a glimpse of somewhere we feel we know or remember. They are also transient. When I go back to the same places they may have disappeared. Heavy rainfall erases the colours, moss spreads over the patterns, and bricks crumble as people lean their bikes against walls. The tiny landscapes are strange and fragile finds. A dear friend once described them as ‘images of time’. I loved that.

Would you like to choose 2 or 3 favourite photographs from your own portfolio and tell us a little about why they are special to you or your experience of making them?

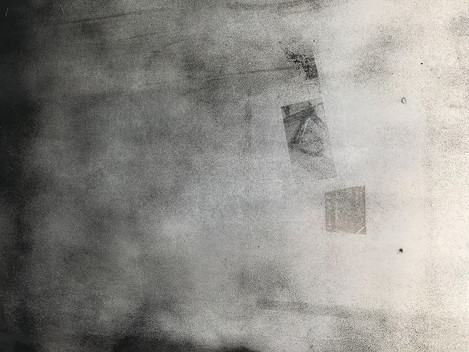

It’s small and a bit blurry, but this is one of my favourite photos. It is the side of a tar truck mending the roads, scorched and blistered by its own heat - a reminder that strange magic can be found anywhere.

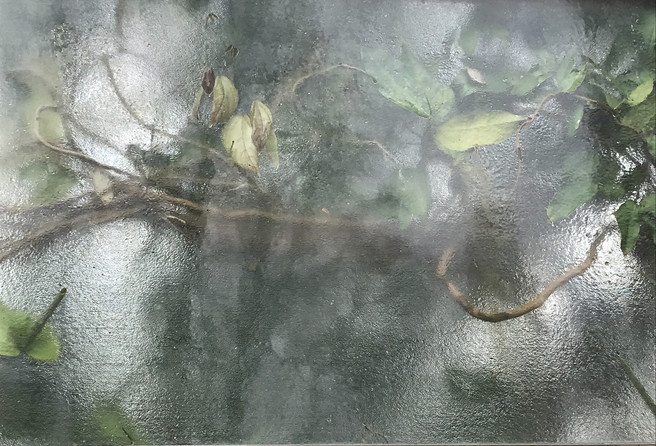

An old house wall, a peg of some kind, some spilt glue perhaps. It was the simplicity of this imaginary landscape that struck me as I saw it transformed into a moon over water.

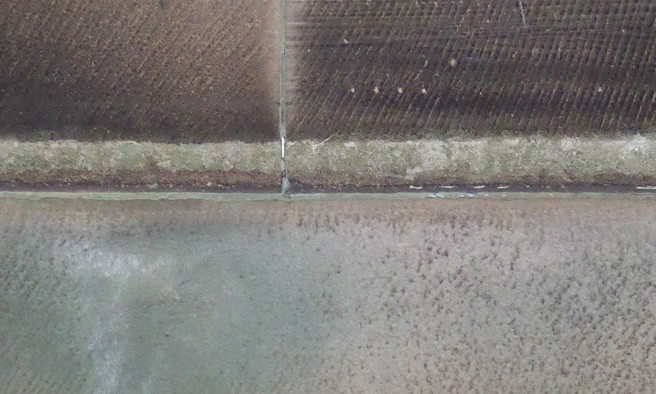

This little fragment caught my eye as I was walking past the water fountain outside the town hall. Sometimes, the loveliest images are hiding in the dullest places.

I sense that camera equipment is simply a means to an end, but perhaps you can tell us if you go on to crop your compositions? How long do you spend playing with possibilities and juxtapositions?

You are right - my aim is very simple: to catch as clearly as I can the fragment I’ve noticed without elaboration or alteration. Occasionally someone will stop me when I’m taking pictures and ask what I am looking at in that dark alley or behind the bus stop. I show them the picture on my camera and then walk a few steps with them to point out the stones they came from. There they are in the wall, and there they are in my camera, and they look just the same. So the work when I get home is not to enhance them but to crop them if needed, and often to turn them sideways or upside down because I had seen their potential from the other way up. Occasionally I re-size them to fit a project or to avoid them being cut off when I post them online, and of course, I have a lot of fun mixing fragments together into collages, at which point I begin to see things very differently.

The question of enhancing the images is interesting to me. Every so often, someone will take one of my images from Twitter, apply various filters, and send it back to me. I can understand they have seen something very basic, which could be smoother, brighter, and sharper, but I can’t agree that the apps and filters have made it ‘better’. They have certainly made it different. The polished, cleaned-up versions returned to me are smarter for sure, and occasionally they look quite wonderful, like background scenes from animated movies or video games, but I don’t recognise them. Any hint of the messiness, the dirt, and the broken ruins they were embedded in has disappeared, and they are now lovely photographs of something quite different. I don’t mean to diminish the value of enhancing and perfecting things, but it doesn’t suit my own work or aesthetic. The magic, for me, is seeing both things at once - that this is obviously a photo of an old brick, and yet we can walk right through it into another world.

Do you go on to print some of your pictures, and if so, how do you like to present them (e.g. paper, size, collage, etc.)? I mention size as I wonder if part of the appeal is to also make viewers look closely and whether the mystery is diluted if enlarged.

The fragments that catch my eye are often just a few inches, and I can’t always get close to them without falling down ditches or climbing over a fence, so the cropped work can often be very small indeed. I take pictures on the move and without a very steady hand, but most of them do seem to catch the dreamlike quality that drew me to them. Because of their small size and imperfect ‘finish’ I can’t imagine them as art prints, and I think that you are right that it’s not just about the quality of the little photos but also that the charm seems very much diminished when they are larger. My published books, which include art and poetry, are all quite small, and I’ve been delighted by how well they have worked. At home, I do make little postcards, bookmarks, gifts, and homemade zines. I have an Epson eco-tank printer, and I use their matte or semi-gloss photo paper.

You mention people looking closely, and that’s a very precious thing. I am continually surprised and delighted that it happens so often, especially on Twitter, the home of fast scrolling. I am always pleased to see the comments and to understand what people are seeing and remembering as they look at the images. My last print book (‘untravelling’ published by Penteract Press) has 55 images, each accompanied by a four line poem, and every line was mixed from a word bank of comments people had made about those images. Most of them were spontaneous replies online, which were very thoughtful and sometimes very moving. I was also travelling on trains a lot at that time, so if I happened to be next to a chatty person, I would show them a few of the images and ask them what they saw. It was an extraordinary experiment, and I’m very grateful to everyone who engaged with the photos and shared their thoughts and visions.

Books seem to be an important and valuable part of your life – both in terms of what you enjoy reading and how you share your images, and it’s clear that you have an affinity for words?

Yes, very much so. I have always loved reading - my walls are full of books, and I have a particular love of poetry. I often add words to my photos or a quote sometimes, not to direct or explain but rather to loosen up the many ways we might engage with it, and I love the verbal responses that enable me to see the images quite differently myself. I am drawn to photographers who invite words into their work. Ian Hill comes to mind as he weaves mythical themes into his walks through the landscape, and Rob Hudson’s beautiful series ‘All Day It Has Rained’, inspired by the Welsh poet Alun Lewis.

During the Covid restrictions, I very much enjoyed George Szirtes’ daily poems online. He captured the strangeness, fear, challenges, and changes so beautifully, using a 10 line format (three classic haiku plus a 5 syllable last line). He has always been very generous and supportive of my photos and used his format to develop my e-book ‘glasshouse’, published by Metambesen. My experience has been that art and poetry weave beautifully with each other through online communities and small independent presses and I am delighted to be a small part of this.

Your images have been featured in a number of books and also in formats that have been made available free to download. This contrasts with a model that often sees people trying to monetise a passion. How did the books come about, and what do you personally feel is important about simply photographing – and sharing – for enjoyment?

Throughout my life, I have been so very grateful for libraries, for free exhibitions, and for people who have shared their work without payment. These things have given me so much richness and wonder, and I would never have been able to access art without that kind of openness and generosity, particularly when I was growing up, and at other disrupted times in my life. I am continually shocked at the prices for exhibitions in some of our main art galleries.

There is something else as well, which is the glimpses I’ve had of how the market leads the art. I have sometimes joined groups of local artists and have submitted work to shows and been included in exhibitions. Most recently, the works were photo backgrounds with pastel markings or collaged found materials. I was delighted to have had sales and to know that people were interested in seeing more work. The majority of requests, however, were for ‘almost the same’ work or similar work in different colours to match potential buyers’ preferences or decor. There were also times when gallery owners who had attended the shows would offer me space, and again I was delighted, but their request was understandably for more of what had sold before rather than anything new or different. As a result, my preference is to work as much as I can with free projects and small experimental presses. I admire them very much for the risks they take and their invaluable support for new material and alternative ways of working.

What difference has photography made to you and to your view of the world? You’ve written captions for your posts that suggest you are comfortable in places where others are not, and observant of and sensitive to the lives that you encounter, which may also be overlooked?

Photography has made my life much richer in many ways. I am appreciating more than ever the interest to be found in what may seem at first to be dull and empty places. I have a richer understanding of time and season which was also very much enhanced during the difficult and often tragic early years of Covid, when time outside was limited, and I challenged myself to find some small treasure every day and close to home. I think it has encouraged me to approach everything with an expectation of openness and possibility, looking ever more closely and never being bored by apparent sameness.

I have always enjoyed walking and travelling alone, but I think that having the camera has enhanced that kind of freedom - stopping as long as I want and walking off track because my eye has been caught. I am aware that for many people, and perhaps especially women, wandering alone is not easy. I am lucky to have always been something of a loner, but I do think that having a purpose and looking for certain kinds of things to work with helps a solo person move more about more confidently, and yes, I am often quite comfortable in isolated spaces and sensitive to their history and meanings. I mentioned this in a piece I wrote for Clare Archibald’s project ‘Lone Women in Flashes of Wilderness’, about walking in cemeteries:

I understand the fears of others - of shadows and lurking strangers, of hidden and unseen things, of ghosts and the scent of death - but I don’t share them. I feel calm in graveyards and free. Their perspective is centuries rather than fleeting moments, there is no urgency. They connect us with memories, open us to ideas, and surround us with deeper things - death, loss, sorrow, yes, but also time, history, meaning-making, and, more than anything, love. Love is the strongest theme here, and it is unhidden, unforgotten, unlost.

Do you have any particular projects or ambitions for the future or themes that you would like to explore further?

So many! I always have several projects on the go and endless folders of work that may or may not become something. I’m very happy to take my time and feel my way...

And finally, is there someone whose photography you enjoy – perhaps someone that we may not have come across - and whose work you think we should feature in a future issue? They can be amateur or professional.

I thought immediately of Jane Rushton, a wonderful artist in the Scottish Highlands. A couple of years ago, she posted online a daily photo taken outside her studio at the edge of the sea. People who know that landscape will be able to guess the scale of the daily changes. It was just the most wonderful thing to watch as the light and weather transformed every aspect of the view. I began to log in each morning just to ‘sit’ on her beach for a while to see and feel the wind and waves, and sky reinvents themselves daily.

Thank you, Mary, it’s been great to talk to you.

If you’d like to see more of Mary’s curated fragments, you’ll find her on Twitter as @maryfrancesness.

Mary’s printed books – ‘untravelling’ and ‘sea pictures' are available from Penteract Press.

Additionally, ‘glasshouse’, ‘Landfall’ and ‘New Worlds in Old Stones’ can be viewed and downloaded without cost at Metambesen.