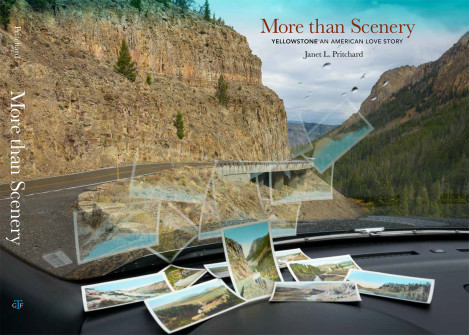

An interview with Janet L. Pritchard

Janet L. Pritchard

Before photography, Pritchard was an outdoor education instructor and spent her youth between the Northeast and Rocky Mountain West in the U.S. She describes herself as geographically bilingual. Her methodology relies on archival materials to guide her depictions of landscapes as expressions of time and place, situating landscapes at the intersection of nature and culture. She is a Professor and graduate advisor at the University of Connecticut.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

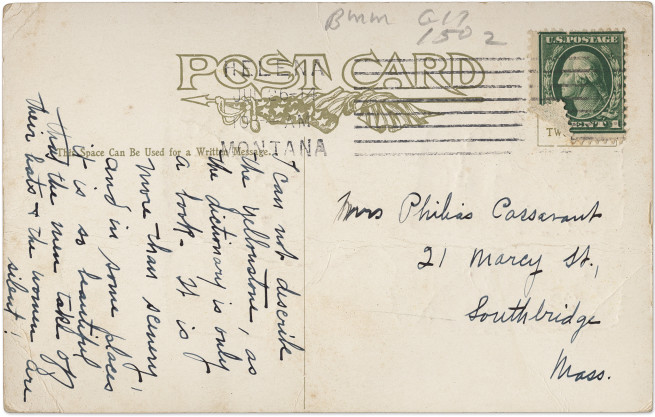

An old Haynes’ picture postcard of Golden Gate Canyon found at a paper antiques show first caught Janet's eye. It transported her back to a place from her childhood. The significant regional and socioeconomic differences in the US, compared to that experienced as a child, had a direct impact on her work as a photographer. Janet uses a methodology called "historical empathy, which relies on archival materials to guide depictions of the complex landscapes found at the intersection of nature and culture." Eager to delve deeper into her latest project, I reached out to Janet for an in-depth conversation about her latest project.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself – where you grew up, what your early interests were, and what you went on to do?

My origin story as a photographer begins with adolescent summers in NW Wyoming, an introduction to a 35mm rangefinder and the darkroom in junior high, and later working as an outdoor education instructor. These experiences influenced much of what followed. Wyoming expanded my sense of place; a manual camera and the darkroom shaped my earliest perception of self as a photographer, and outdoor education confirmed my fondness for teaching. I discuss this story further in my essay “Education of a Photographer” in More than Scenery.

At what point did photography become more than a hobby? Did anything in particular prompt this? You worked as an outdoor education instructor. How did you transition to a photographer?

Once in the darkroom, photography was never a hobby; it was a passion. Early on, I sensed it would shape my life. On a most fundamental level, photography is my way of being in the world. Working in outdoor education was also a good fit for many parts of me.

Tell me about the photographers or artists that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography, and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

I read widely and variously. I look deeply at work in many modes, but photography and painting hold my attention the longest. Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander, Emmet Gowin, and Andre Kertesz are a few photographers I studied in my youth and still enjoy. A little later, Linda Connor’s work held my gaze. Looking at and thinking about work by other women became a strong focus as I wrestled with where I fit in the medium's traditions and feminist theory. Critical theory encouraged my inclination to lean on other intellectual disciplines. There is a lot of great photography being made these days, and it’s a joy to follow the work of many younger artists.

On your website, you write about being “geographically bilingual and having early experiences leading to an awareness of significant regional differences within the United States.” Tell us more about how this experience informed your view of the different landscapes in the regions and how that impacted your creativity.

People often talk about the importance of travel and being a global citizen. While I believe that to be true, I also worry that too few people in the U.S. have experienced the sharp regional differences at home. If we were more aware, we might also be more empathetic. Spending summers in a very different part of the country at a young age opened my eyes to significant regional and socioeconomic differences in a way that drives my work. My photographs frequently tap into an awareness that even when a place looks familiar, a life there may differ significantly from my experiences. I work to remember this and use research to understand such differences.

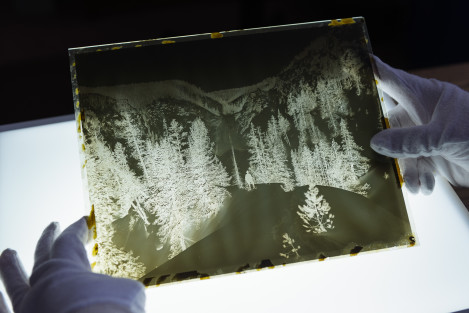

You mention a methodology you call ‘historical empathy, which relies on archival materials to guide depictions of the complex landscapes found at the intersection of nature and culture.” Can you tell us more about this methodology, how you devised it and how you use this process in your creativity?

As Barry Lopez suggests, I understand landscapes as the intersection of nature and culture. Historical empathy as a method grew out of this belief, but historian Robert Gross coined the phrase to describe my methodology some years ago when writing a letter to support my work; it stuck. I had the benefit of a vital “classical” education growing up. Still, I railed against the holdover beliefs from New Critical Theory that a work must be interpreted solely using intrinsic information and excluding historical, social, economic, and biographical influences from “reading” a work. This view of art felt limiting, so I began digging in other places to expand my understanding. Now, I lean heavily on different ways of knowing to understand the landscapes I photograph more deeply.

Your current position is a Professor of Art, Area Coordinator, and Graduate Advisor at the University of Connecticut. Has teaching influenced your style and approach to photography?

How can teaching photography not influence my photographic work? I had a student who opened my eyes to the obvious. He was a golfer who competed in college. Afterwards, he taught as a golf pro, and his game improved.

More than Scenery - Yellowstone, An American Love Story was inspired by a vintage picture postcard of Golden Gate Canyon by Frank Jay Haynes. Can you tell us more about how this sparked the idea of the project and how it evolved?

The view of Golden Gate Canyon caught my attention after looking through the Wyoming cards at a paper antiques show. It’s a classic 19th-century proscenium picture space borrowed from painting by Western exploration survey photographers of the 1870s and ’80s. I noticed multiple copies of this view and thought it strange since it is not known today as one of Yellowstone’s “greatest hits.” When I turned it over, the message took me back to that childhood place of wonder tempered by a lifetime of work in landscape photography and raising a family: “I can not describe the Yellowstone, as the dictionary is only a book. It is more than scenery, and in some places, it is so beautiful that the men take off their hats & the women are Silent!”

Lucy Lipard wrote the introduction to your book. What’s your connection to Lucy, and how did this collaboration come about?

When I returned to finish my undergraduate degree at the University of Colorado, an influential professor suggested I read a recent book by Lucy Lippard, From the Center, a 1976 collection of feminist essays. This book validated much of my resistance to New Critical Theory. I was surprised later to learn the extent of her interest in landscape. Later, books, Overlay, 1983, Mixed Blessings, 1990,. Lure of the Local, 1998, and On the Beaten Track, 1999 all informed my work. Over the years, our paths crossed in various informal ways, and we had mutual colleagues and acquaintances. She had previously worked with George Thompson, my publisher, and I was honoured and pleased when she accepted our offer to write.

In the introduction, Romancing the West, Lucy writes, “The subject of this book is not another fruitless attempt to describe or simulate the effect of Yellowstone’s magnificent “scenery” so much as it explores human responses and human presence, including the artist/author’s.” (page 13) How did you approach capturing these human elements?

This project was grounded in the visitor’s experience of the park from my first reading of the vintage postcard quote. Trying to imagine visiting Yellowstone as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity shaped my perspective. From there, my curiosity led the way. However, it took time for the book’s unique structure of the three portfolios, “Views from Wonderland,” “Collecting Yellowstone,” and “Stories from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem,” to unfold. As I worked, my appreciation for the complexity of the park increased; what I paid attention to changed, and where I pointed my lens reflected those changes. I came to think of the portfolios as triangulating the park’s heart from distinct vantage points.

“We are accustomed to calendar photographs of our stunning national parks, and, more recently, we are also exposed to the critical landscape photographers who inform us about the downsides of human impacts on the scenery. Pritchard’s rejection of grandiosity is suggested by a deceptively casual approach to photography (bolstered by extensive thought and historical research) that contradicts the expected coffee-table/calendar mode and testifies to the artist’s vision, acumen and commitment.” (page 14) Was this an intended style of photography, or did it evolve from your trips into Yellowstone? Do you think that ‘grandiosity’ can get in the way of communication?

The “style” of this work, described as a “rejection of grandiosity” by Lippard, is intentional. It is the outgrowth of questions I have asked since my undergraduate years in Boulder, photographing the foothills along the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies. There, poised with my view camera along the dividing line of the eastern plains and western mountains, I first questioned my place in the photography. Pushing against the male-dominated genre of landscape, I depicted the “grand view” through a scrim of cottonwood leaves, forcing the viewer to focus on the ordinary rather than the extraordinary. My strategy in More than Scenery is “a deceptively casual approach,” which rejects the “coffee-table/calendar mode.” My “style” in More than Scenery lies at the intersection of the calendar and the critical photograph. While my “style” is neither, I’ve learned lessons from both.

“The heavy hand of humankind is depicted innocently: a hand holding a chunk of obsidian taken from the cliff in the background" (page 108), "a fleeced arm holding a picture of a waterfall in front of the real place" (page 10)—nature at home and decontextualised.” (page 14). When you were making the images, did you think about the messages that you wanted to communicate to the viewer? How did you go about achieving this? Did you think about the messages that you wanted to convey and then made the images or vice versa? Or was there a different process, perhaps through curation?

A photographer/artist makes many choices along the course of a project. One’s sense of a project shifts and changes in response to work, research, reviewing results, moving this image next to that one, and learning back from one’s work, always working to understand what one has done rather than what one thinks they have done. New choices are made, hypotheses are tested, adaptations are adjusted often on the fly, and so on. In the beginning, I had curiosity. That identified a place to start.

I refined the concept as I worked, and the process became more directed, but I always left room for chance. This project, spanning thousands of photographs, required frequent reassessment, checking in with what was and wasn’t working, and always keeping the strong outliers in my mind because as an emphasis shifted here or there, gaps might open up, making room for pictures that hadn’t fit before. Final edits left some stunning photographs out of the book for the good of the whole.

“Hiding behind the scenes of Pritchard’s photographs are the invaluable and still unknown ecosystems ignored by most visitors, cherished by scientists worried about climate change and the disappearance of species. They are finally becoming a focus of beleaguered park management, whose budgets were constantly being raided by an unsympathetic federal administration.” Was climate change something that you were actively thinking about when you were working on the project? Was there a clear message that you wanted to leave with the viewer? (page 15)

An awareness of the impacts of climate change is unavoidable for anyone paying attention.

The clear message of this book is simple if complex: Yellowstone is not one thing. As Lippard says, this is not a coffee table book. More than Scenery weaves a picture of a complicated landscape that appears one thing to visitors, another to those steeped in its histories, and yet again another when seen through the lens of recourse and management issues.

“The photographs I have made of Yellowstone National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem surrounding it are not a tale of paradise lost but are sparked by the memories of my life in Wyoming when a dream turned real. That landscape of childhood and adolescent wonder set the stage for my life as a photographer, allowing me to connect nature with family, love, belonging, and separation. A lifetime of longing for the place where I was not living.“ Do you think completing this project has helped you heal the sense of separation and the longing you had?

You ask if this project healed my sense of separation and longing. The longing is a comforting presence, an understanding that my life plays out over a more extensive terrain than any one place. I’ve often thought my work was about paths not taken in my life. There are any number of other doors I could have walked through when I was younger. I chose photography, which has allowed me to explore a number of those paths, albeit differently than if I had made a career of X, Y, or Z. With a camera as my guide, I can dip into history, literature, writing, environmental studies, and science, etc. Although it’s true, I must sometimes remind myself I am not a historian or any of those other things and prioritise the needs of my chosen path.

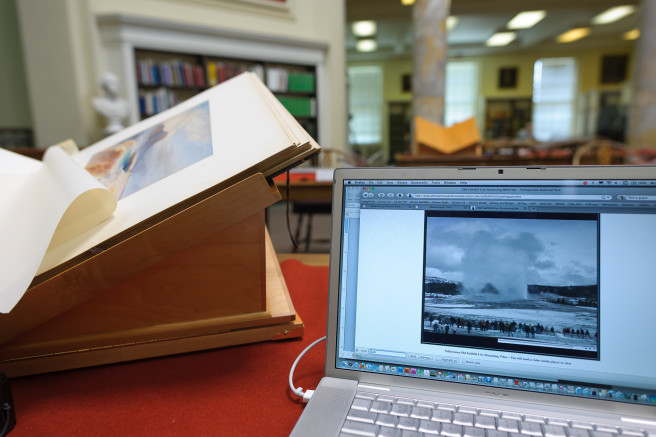

“Research for the book began beneath the generous dome of the American Antiquarian Society’s reading room in Worcester, Massachusetts, where I was a Jay and Deborah Last Fellow in June 2008. Sitting in the library for forty hours a week for four weeks was not my natural habitat. And yet, the strength of my belief in the value of learning more about Yellowstone’s history and origin story compelled me.” Tell us more about the research that you did into Yellowstone. Why was it so important to you to understand more about the history and origin?

When I was younger, I visited Yellowstone for less than a day on my great American road trip the summer before University. My friend and I drove in the west entrance, watched Old Faithful erupt, and left through the south gate because it was crowded, and we were impatient. Later in life, I appreciated the once-in-a-lifetime experience for a visitor in a way I could not when I was young.

In contrast, today, visitors use personal devices to capture their memories, changing from film to digital point-and-shoot cameras to cell phones and even illegal drones throughout this project. Selfie sticks are now everywhere, and photo frenzies happen. Through the eyes of science, the large boulders scattered in the Lamar Valley were named glacial erratic, telling a story of ice sheets long ago. The trees sheltered in their lee speak of dominant weather patterns, yielding the expressive term nurse rocks. These few examples highlight how enlarging my knowledge changes my understanding, which guides my camera.

“Six weeks of fieldwork in Yellowstone began to shape the project. I saw common threads of shared experiences in the Yellowstone landscape by photographing people visiting the park. Through numerous visits over the years and countless hours in libraries, museums, and any place else where I could find a reference to the park, More than Scenery evolved.” Could you expand on how the project evolved and comment on how it changed from your initial ideas? (page 25)

Initially, the quote called to me. I had faith in my process to follow that call, but More than Scenery evolved as I worked in the field and various archives. The portfolio structure traces that process. When I first went to Yellowstone in the fall of 2008, I could not escape the visitors, and “Views from Wonderland” was conceived. Although I spent time in the American Antiquarian Society reading room before my first visit to the park, those photographs of books were intended to be notes. It was not until the end of my fellowship that I realised these images had the potential for more, and “Collecting Yellowstone” took flight. “Stories from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” about the natural history wonders and resource and management issues took longer. Not because I wasn’t making these images early on but because I wanted this project to be more than pretty pictures or another condemnation of Manifest Destiny and our wrecking ball approach to settlement. Finding my place in that took time.

“Three thematic portfolios comprise the heart of this book. Inspired by the Haynes postcard, which served as my benchmark, I photographed early twenty-first-century visitors to the park. Visiting Yellowstone is a heavily mediated experience for most. Visitors drive through “Wonderland” (page 26). Tell us about the three thematic portfolios and how you built the narrative around them.

Although I touched on this above, I will add a bit. The three-part structure of More than Scenery is unusual and only emerged slowly. At first, I believed I needed to weave the pictures together to present a more cohesive narrative. However, I found myself resisting and so delayed.

“Stories from the Greater Ecosystem (Portfolio III) took shape when I more carefully considered our role as stewards coming to appreciate the wonders of the Yellowstone landscape fully.” (page 26) The challenges of popularity and protection, ownership and wilderness are difficult to distil. What conclusions did you draw from your work on this topic?

What did I conclude? My appreciation for the messiness that is Yellowstone evolved. I grew more empathetic to the sincerity of a one-time visitor’s wonder but cautious of their ignorance, which can lead to danger. I began with a sense that the origin story of the park was complex, pitting centuries of indigenous habitation against the brutality of Manifest Destiny. My increased knowledge about the economic incentives for establishing the park fuelled this fire. I also learned more about the management issues driven by the diversity of stakeholders across the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. The short answer is yes; my most concrete conclusion is that there is nothing simple about the park. Yellowstone is one of our most iconic landscapes and a microcosm for the enormous challenges we face in the twenty-first century as we struggle to know how to steward the land, right the wrongs of the past, and leverage science to develop plans for a changing future.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs from the book are and a little bit about them (please include these images in the ones you send over)

Haynes’ picture postcards of Golden Gate Canyon

Wow, I can only choose three favourites: that’s tough, but I can tell you about the five that summarise the project. Haynes’ picture postcards of Golden Gate Canyon first caught my eye, but one held the provocative quotation that started me on this path [p. 2–3].

Bison (Bison, Bison) Along the Lamar River

Next, “Bison (Bison, Bison) Along the Lamar River” [p. 33] shows a woman viewing Bison through the window of a Yellowstone Association tour bus. The woman is safely seated behind glass, ironically protecting the animals and herself.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone by Thomas Moran

“The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone by Thomas Moran,” which hangs in Lobby 2N at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C., is Moran’s most famous painting. Marketed in the 19th century as a wonder, viewers paid a sum to see the big reveal when curtains were drawn aside [p. 32]. Museums like parks preserve heritage, and what could be more symbolic of our idea, the good and the bad of it, than a famous painting of an even more renowned view hanging in a preeminent museum?

Rose Creek Acclimation Pens

“Rose Creek Acclimation Pens” were used in 1995 and 1996 to house Gray wolves brought down from Canada for reintroduction [p. 154]. Extirpated in 1926, by the mid-1940s, the perception of National Park Service rangers was that a mistake had been made; the ecosystem needed its apex predator to thrive.

Emerald Pool

“Emerald Pool” is an example of the natural history wonders that draw over four million visitors from around the world to visit Yellowstone each season [p. 179].

My first glimpse of this was in a woodblock print of a Hayden Survey photograph by William Henry Jackson published in the Twelfth Annual Report of the Hayden Survey, a U.S. government document published in 1878. The reproduction captured my attention, and I have visited the pool numerous times (see plate 3, p. 78).

Were there many key photographs that you knew would succeed when you took them? Conversely, did some of your pre-planned images fail in execution?

Some photographs stood apart early on, and I felt some were gifts while pushing the shutter release—others required multiple visits to a site. Some days, I arrived at sites and knew the stars were aligned, the weather was what I hoped for, the time of year would yield this information versus that, etc. If the photograph involves people, luck plays a more significant role. But no matter what kind of photograph I hoped to make, perseverance played a role in achieving my desired results.

Sequencing is obviously important - how do you manage the flow of the images and visual narrative when you're working on a book?

Funny you should ask this. I have understood the role of sequencing in a book of photographs ever since encountering the work of Duane Michal’s and Robert Frank’s The Americans when young, but I found with this book, I wasn’t particularly good at it. I knew which photographs belonged in which portfolio and recognized critical pictures to include. It was also clear to me which sequences did not work and when images needed to be sacrificed for the greater good, or empty pages functioned well as breathers. However, the subtleties of movement from this page to that eluded me at times, and for this, I leaned heavily on advice from George Thompson. I am grateful for his support.

What have been the biggest lessons you’ve learned about the process of printing (and preparing to print) a book?

The biggest lesson I learned is that I will go on press next time. Trying to communicate about colour through the designer David Skolkin to the printer in another country was challenging. David went to great lengths, but it took extra effort and patience on the part of the team; everyone was great to work with, but being there would have made things more accessible. Could the results have been better? We’ll never know.

Although the equipment choice is secondary to your own processes, it inevitably affects the way we work to some extent. What equipment do you currently use, and why did you choose it?

All equipment, cameras and tripods, computers and hard drives, and all the endless bits and pieces serve a purpose; I let function drive my choices. I used many cameras during this project. Most of the pictures in the book were made with DSLR cameras, which changed with availability. A few were made with mirrorless cameras, and a few scans are also included. I used digital point-and-shoot cameras for notes and, later, my iPhone. A medium-format digital camera accompanied me on a few early trips but never fit my needs. I finished the project with a Nikon D850 and would love to have had that camera for the entire project. However, now that I have returned to Hasselblad, I can’t imagine a camera more suited to my working methods. I have used Macs since 1986 and Epson printers since 1995. I see no reason to change. But cameras don’t make pictures; people do, so I included the essay “Education of a Photographer” to address the larger question of how I became the photographer I am.

What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

I am currently in the midst of another long project. Photographs in Abiding River: Connecticut River Views & Stories expressively document the land and riverscape of the Connecticut River and its watershed.

Lastly, I’d like to offer you a soapbox for something related to the natural world, the benefits of photography, or just living a good life... What would you like to say to readers or encourage them to do?

Photography is my way of being in the world. It allows me to travel paths not otherwise taken, to spend time outdoors, which nourishes my soul, and to add something to the world. In short, it helps keep me sane in a world where I might otherwise feel powerless. My family keeps me tethered to and enriches my day-to-day life, while photography provides a place to dream; the balance feeds me emotionally and intellectually. I am fortunate and wish life could be so rewarding for everyone. The opening sentence of my Acknowledgments section says it all: “I have the good fortune of a guiding passion and the security of a supportive family without whom none of this would have happened.”

You can buy More than Scenery: Yellowstone Am American Love Story from Casemate UK or other online retailers.