A Photographic Project

Sandy Wotton

During my working life as a scientist, photography was my relaxation and creative outlet; as a retiree, it has become my major occupation. My camera is always with me and using it hand-held gives me freedom to explore visually and experience emotionally any subject at any time. I work mainly in colour, made easier by digital technology in the taking and printing of my photographs. I also enjoy making hand-made books of various kinds, combining my images with short pieces of writing. I am particularly drawn to design and detail in natural environments, where I love walking, observing and reflecting.

Paul Wotton

Photography has been essential to my way of seeing the world for many years, as a powerful medium for expression and storytelling, a good creative outlet and an antidote to a career in clinical and academic veterinary medicine. My desire is to try to tell stories with photographic images, especially around the influence of past and present human activities on the landscape and the effects of natural forces, such as wind and water. I use digital and film-based media and work in monochrome, as I feel the form and texture of the subject are shown better without the distraction of colour. We photograph mainly in Scotland and live in rural Stirlingshire.

At first glance, it could be any ruined cottage standing abandoned in a moorland landscape, but this is no ordinary derelict cottage, nor is this any ordinary moorland.

A’ Mhòine (The Moss) is a large area of blanket peat bog covering most of the Tongue peninsula on the north coast of the Scottish mainland. Today, it is part of the ‘Flow Country’, which extends over wide areas of Sutherland and Caithness. It is managed by a number of organisations working to maintain and restore these rare peatlands for the benefit of people and wildlife and to return them to the important role of storing carbon absorbed from the atmosphere. Their efforts have been rewarded by the recent recognition of the Flow Country as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

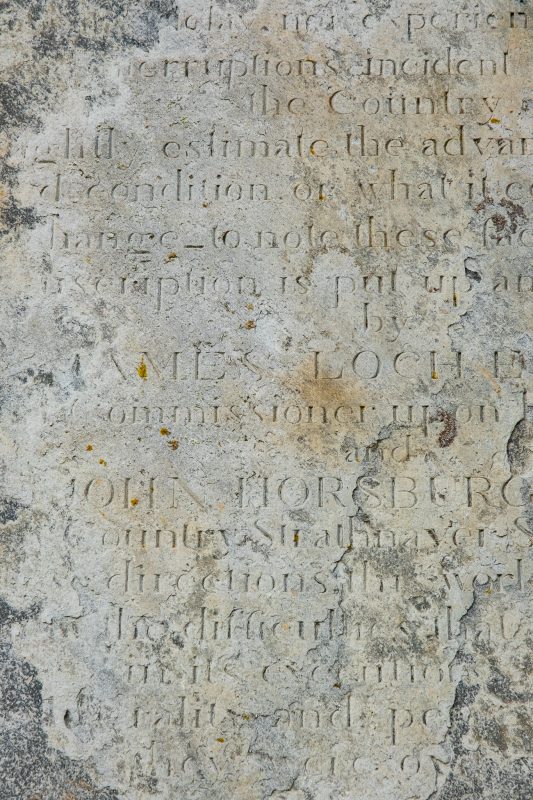

Meanwhile, Moine House seems a rather grand name for what was, even when it was first built in 1830, a humble abode consisting of two ground-floor rooms and an attic. A large plaque on the east gable bears an inscription, now almost illegible, which tells the story of the house and the 14 miles of road that was built at the same time across A’ Mhòine, from Loch Eribol and Loch Hope in the west to the Kyle of Tongue in the east. The inscription begins with an explanation:

This house erected for the refuge of the traveller was to commemorate the construction of the Road across the deep and dangerous morass of the Moin, impracticable to all but the hardy and active native; to him even it was a day of toil and of labour. This road was made in the year 1830 at the sole expense of the Marquess of Stafford .

The Marquess is better known today as the Duke of Sutherland and as one of the most blameworthy of the landlords in the area, along with Lord Reay, for their overzealous “clearing” of crofters from their homes in villages such as Rosal and Achanlochy in Strathnaver. The inscription goes on to praise the evident improvement, warranting the plaque to be …

...put up and dedicated by James Loch Esq. M.P., Auditor and Commissioner ... and John Horseburgh Esq., factor for … Reay County, Strathnaver, Strath Halladale and Assynt, under whose direction this work was executed and who alone know the difficulties that occurred in its execution and the liberality and perseverance by which they were overcome.~Peter Lawson Surveyor

While these names are still discernible, no mention is made of the crofters by whose labour the road was actually built. Previously displaced from their homes in Strathnaver, etc., and struggling to make a living on the coast to which they had been required to move, they were at least paid for their labour constructing or improving the roads in the area. The problem of constructing a road over a bog was overcome by using bundles of heather laid under the surface to prevent it sinking. In the 1939 edition of the guidebook ‘Scotland for Everyman’ by H.A. Piehler, he calls the road “The Tongue road” and describes it as being in “fair condition” as it “… crosses a dreary peat-moss called the Mhoine, rising to 741 feet, with splendid views, and then descending the shore of the Kyle of Tongue”. This old single-track road was only replaced in 1993 by the new A838, which runs just north of the house.

Moine House fared less well over time. Intended as a halfway house for weary travellers crossing the bog, it was also a family home and in 1881 it housed three generations, totalling four adults and five grandchildren. The last occupant seems to have been one of the grandchildren who was three years old in 1881. There was no mention of MoineHousee in the 1939 guidebook, but in 1981, when it became a C-listed building, it was described as being in a poor state, although still having a roof. The roof was removed for safety reasons in the 1990’s and photographs in 2020 show the interior walls used for artistic graffiti (later removed). Today, it still awaits possible restoration, adorned only with the last licks of blue-painted woodwork and yellow lichens.

For us, this was an ideal photographic location on our trip to north Sutherland in October 2024. We had several projects in mind, including the ecology of the Flow Country peatlands and the stories of the Highland Clearances.

Paul has a long-standing interest in the consequences for both people and the landscape of the Highland clearances, and we had already visited and been very moved by the stories and remains at Achanlochy and Rosal. The road across A' Mhoine was built about 10 years after the end of the clearances, but it illustrated a further manifestation of the difficulty of crofters needing to find a living after removal to poor agricultural land on the coast. On the peat bog itself, he found the movement of the vegetation on windswept Moine and around the house grabbed his attention, and the depths of the peaty pools gripped his imagination.

Sandy with her passion for ‘primitive’ plants such as mosses, lichens, liverworts and their environments, was very much in her element on A’ Moine, searching for different types of lichens and sphagnum mosses and appreciating how their life cycles create the dynamic and very substance of peat bogs, along with other bog or water-loving plants. She used vertical framing to convey the expanse of deep colours of the peat bog laid before the distant mountains while maintaining some plant detail in the foreground.

While we share interests in the natural world, landscape photography and social history, and often take photographs of similar subjects, our approaches differ to some degree.

Sandy likes to wander with a camera in hand, using one camera with a short telephoto lens. She looks for interesting compositions in the landscape, but particularly for smaller details. Often, she finds that a thread emerges (an idea, a feeling, the lines of a poem, a memory, even a story) that might connect the experience and link with the images. She takes mainly colour photographs and likes to make a series of images for a blog or small handmade books.

Paul works in monochrome with digital and medium format film cameras, nearly always using a tripod, which slows down the process and allows him to use slow shutter speeds or multiple exposures to capture the mood and movement of a scene in a mindful way in single or sequences of images. In our image-making, we are both interested not only in the feel of a place or subject and the emotions it gives rise to, but also in the notion of time passing, the paradox of past and future represented in the present.