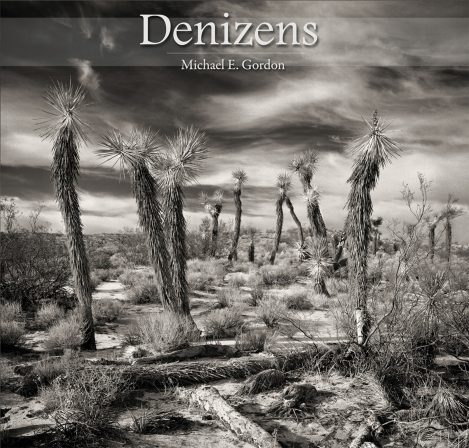

Denizens

Michael Gordon

Professional photographic artist, educator, and activist specialising in monochromatic impressions of the California desert.

A Study of the California Desert

It's Tim Parkin writing, I just wanted to take a moment to give some background to my experiences with digital book printing. I have looked at this process in the past (over a decade ago) and was fairly quick to eliminate it for anything serious, and the thought of using it to print fine art black and white photographs was laughable. At the time, the only offer in town was Blurb, and it was fair to say that the results were poor. The screen (dot pattern) was coarse, the inks were not particularly vibrant, and the accuracy of registration meant that colour shifts were common. At the time, it was CMYK offset litho or the highway! Since then, I’ve seen a couple of pretty decent catalogs and one book pass by my desk, but it was when I was at Johnson’s of Nantwich that I discovered how much this printing methodology had improved. John Macmillan made a proof printing of our Natural Landscape book, and I was very impressed at both the colour accuracy and the fine detail.

I was equally surprised and pleased when I received my copy of Michael Gordon’s book, and initially thought it was actually litho as the telltale magentas and greens of the previous black and white prints I’d seen on digital were totally absent. I spent a few minutes with a loupe going from page to page until I finally said “that’s good enough”.

I’m obviously not saying it’s good enough to replace platinum printing, tritone litho or toned FB prints. What I’m saying is that it’s good enough to portray acceptable reproductions of good photography that I’m willing to spend some of my own money on it. It’s good enough to communicate your photographic ideas to your audience. It’s good enough to forget about and enjoy the quality of the photographs.

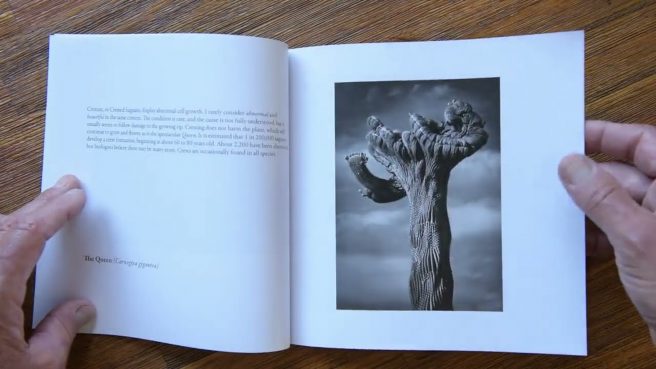

So that’s what I did for the next hour or two. I spent a while with Michael’s black and white photographs of the California desert’s less mobile occupants. And there are some sublime images in here, from pictorial swirls of my favourite Juniper photograph taken with Michael’s Wollensack Verito lens (whose ownership and use I’m a little envious off) to more contemporary portrayals. I particularly enjoyed the narrative throughout, opening a window into those desert Denizens that Michael obviously loves so much (apart from maybe the cholla cactus - devious little things!).

The fact that the work is up to Michael’s high standards is a testament to how much digital printing has improved in the last decade or so, and it’s well worth a purchase (if postage to your location isn’t too onerous!).

Tim Parkin

An affordable, low-risk alternative to traditional book printing.

A photography book, or monograph, has always been the most affordable and uniquely personal way to own and to study photographs. For photographers, monographs allow more of our images to reach more people than any exhibition ever could. And for the cost of a single print, a number of monographs could be added to a book collection, potentially containing hundreds of photographs. Many photographers enjoy robust book collections and libraries whose inspiration we can return to again and again. Is there a photographer out there who hasn’t dreamed of making their own?

One of the first things the fine art coffee table photography book aspirant learns about self-publishing is that the cost of producing your dream book can run into the tens of thousands of dollars, depending upon your book’s specifications (physical size; page count; dustjacket or linen cover; etc.) and your threshold for quality. Self-publishing is neither easy nor simple: You might spend upward of a year or more at your computer constructing your book, and you may believe your toil is finally over when you submit your final PDF to the print house. But palettes of books will soon arrive, and they will not sell themselves.

In early 2009, Brooks Jensen of LensWork published an essay titled “Some Unvarnished Truths About Book Publishing” that directed me toward a course of prudence. My data awareness and fiscal conservatism are far larger than my ego, so I took Jensen’s numbers and words with great caution and shelved any ideas about producing a large, high-end coffee table book until some unknown time in the future. For this article, I adjusted Jensen’s 2009 numbers to today: as of 2024, 80% of books published do not earn back their advance, and 90% of books published do not make a profit (all books; and photography books don’t do as well as other categories). The destabilizing hit my ego would take would be far greater than any reward I could imagine if I were to produce a “remaindered” book (those $5 undersold blowout specials found at brick-and-mortar bookstores) or one that I would be left with unsold cartons of in my garage. These numbers should be an even more critical consideration to you if your book and content are more niche-oriented than of universal appeal, as is the case with my latest book, Denizens.