A Project of Contrasts

Tina Freeman

Tina Freeman is a photographer of landscapes, architecture, portraits, and interiors whose life work has focused on the exploration of physical environments. Acclaimed for photographing architecture and interiors in her native New Orleans, the U.S., and Europe, she has simultaneously sought to capture the subtle beauty of Louisiana’s natural landscape through her discerning lens. Acknowledged for her mastery of natural light, Freeman’s photography is above all characterised by a sense of tranquillity and peace.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

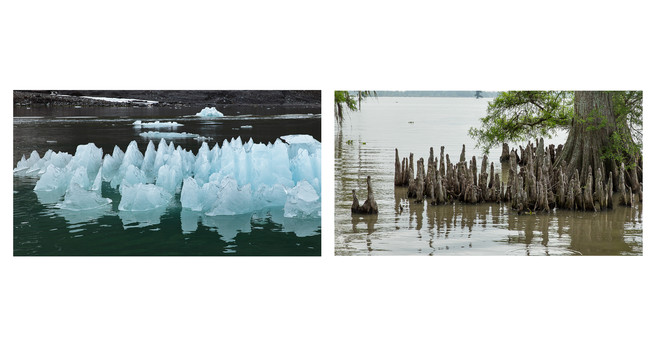

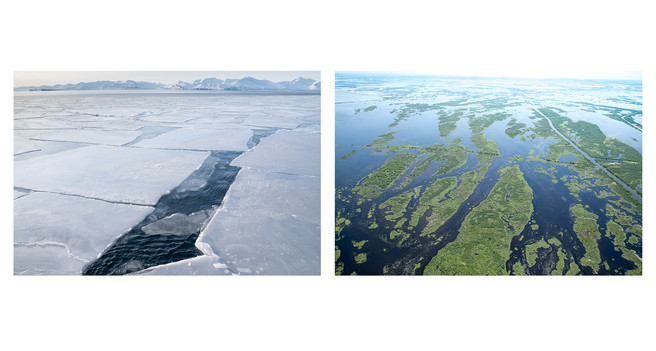

Over seven years Tina has photographed the Louisiana wetlands and the glacial landscapes of the Arctic and the Antarctic. The project Lamentations is a series of diptychs that function as stories about climate change, ecological balance, and the connectedness of things across time and space. We talk to Tina to find out about the project and how it all started.

What sparked your passion for photography?

My father was an avid amateur photographer, and my grandfather made early 35mm films of his travels (unfortunately on nitrate-based stock, so they self-destructed). During our family outings, my father always had a Leica with him, and later a Minox. When I was twelve, someone offered to teach me how to use a darkroom. I jumped at the chance, in no small part because the offer came in the middle of the hot New Orleans summer.

Tell me about the photographers or artists that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

My parents subscribed to National Geographic, but it was the black and white images in Life magazine that captured my imagination. I would devour Life as soon as it came through the mail slot, especially savouring the work of Margaret Bourke-White and W. Eugene Smith.

While I was at the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles, I became enamoured with Western photographers: Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and, to a lesser extent, Ansel Adams.

In my early twenties, Irving Penn’s sumptuous work—still lifes, portraits, platinum prints, and his voluptuous nudes—called to me. In about 1977 Henry Geldzahler introduced us at lunch in the curator’s dining room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an elegant room to the left of the entrance, where the coat check is today. I had been making colour Xerox prints of my work and showed them to him. Penn seemed a bit horrified at the idea that the color Xeroxes of the time, which were far different from the colour copies we have today, might be around forever.

When Penn offered me a job as an assistant, I instantly accepted. But the universe conspired to complicate my decision. Shortly after the meeting, the New Orleans Museum of Art offered me the curatorship of the photography collection. Strangely enough, I don’t remember my process in deciding to go back home, but I did.

Your background is in interior and architecture photography. How and why did you engage with landscape photography and what inspired that move?

After I graduated from Art Center, I felt portraiture was the most challenging area for me, so I embarked on photographing just about everyone I met: David Hockney, Andy Warhol, Diana Vreeland, Paloma Picasso, and many more. Then at some point, I realised the interiors surrounding the people also made a type of portrait. I began to make portraits without the people, hence the beginning of my interiors.

I was working primarily in black and white. Then, in the 1980s, I began to do commercial magazine work, and the editors specified that I use transparency film. My first assignment came out of a cold call to Connoisseur, the jewel in the crown of Hearst publishing. I decided this was where I wanted to work; I made an appointment, and they hired me. My first assignment turned out to be a cover and 13 images of a chateau in France.

What set me apart in those days was my use of what looked like natural lighting. I was striving to make the interiors look like they did when you were in the room. The overall style then was to over-light, balancing the exposure inside with the view outside the windows. By contrast, I would use a very small Dyna Lite strobe box with three heads to ensure that I filled the shadows a bit. When I shoot interiors today, I still use this same strobe.

Who has helped you in realising your photographic ambitions over the past few years?

The University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press published the Artist Spaces book as well as Lamentations. The Ogden Museum of Southern Art and Curator Bradley Sumrall, as well as the Paul and Lulu Hilliard University Art Museum and Director LouAnne Greenwald, exhibited Artist Spaces.

Susan Taylor, Director, and Russell Lord, Curator of Photography, at the New Orleans Museum of Art have nurtured the Lamentations project from its beginning, deciding a couple of years into the project to exhibit it and co-publish the book.

Your book "Artist Spaces New Orleans" gives a comprehensive portrait of the city's artists and their relationship to space. How did this series make you think about your photography and how interconnected that is with other aspects of your life?

I began shooting artists and their interiors in the 1970s. It was mostly portraits of the artists, but I was very aware of the interiors as well. In October of 1988, my photographs of Man Ray’s studio on Rue Ferou in Paris ran in Art and Antiques magazine: six images plus the cover. In August of 1988, in Connoisseur magazine, I photographed the very same interiors that J.M.W. Turner had painted in watercolours. This amazing assignment changed the way I saw my own spaces.

I photographed many other artists’ spaces before the book, but they were on film. It was easier to layout a book with digital images, so I used my first pro-level DSLR, starting in 2005 before Hurricane Katrina, and worked until 2014 on images for the book.

You were the Senior Curator of Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art. What did this role entail?

I was Curator of Photography at NOMA from 1977-1982. It was a heady time to be collecting photographs. The National Endowment for the Arts made a number of large grants that helped the museum purchase contemporary photographers’ work.

I mounted numerous exhibitions including Diverse Images, an overview of the collection of the museum as it stood in 1978.

I was responsible for producing the following books:

- Leslie Gill: A Classical Approach to Photography. New Orleans, La: New Orleans Museum of Art. 1984.

- The Photographs of Mother St. Croix. New Orleans, La: New Orleans Museum of Art. 1982.

- Diverse Images: Photographs from the New Orleans Museum of Art. Garden City, NY: Amphoto. 1979.

- Also, I was responsible for numerous contributions to Arts Quarterly, New Orleans, La.

The photography collection in the NOMA is extensive, tell us more about the collection and a bit about the role of New Orleans in the history of photography.

The first documented photographs of New Orleans are daguerreotypes by Jules Leon made in 1840, only one year after Daguerre went public with the process in 1839.

My primary source for the following information is Russell Lord’s excellent 2018 book on the photography collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art, published by Aperture: Looking Again.

In April of 1918, the museum exhibited An Exhibition of Pictorial Photography by American Artists. The museum began its own collection of photography in 1973.

In 1932 there was an exhibition of Margaret Bourke-White’s work, and in 1936 and 1949, Clarence John Laughlin, the American Surrealist photographer, exhibited at the museum.

There were numerous exhibitions of photography in the 1950s and 60s. In 1973, John Bullard became the Director of the museum and began a collecting programme and by 1974 had a permanent Curator of Photography, making The New Orleans Museum of Art perhaps the first southeastern regional museum to have a permanent collection of photography. I was the second Curator of Photography.

The collection now numbers over twelve thousand images.

Over the past seven years, you have photographed the Louisiana wetlands, Arctic and Antarctic glaciers in your project "Lamentations" Where did it all start?

When I was about four, I went on a summer vacation with my parents to the mountains. The air was warm, however, pockets of snow remained in the shadows. I was terrified: this cold, white stuff made no sense. Perhaps this started my fascination.

After working on Artist Spaces I was looking for another project. This series started with a trip to Antarctica in 2011 with about 80 other photographers. The undertaking was a huge commitment, but it opened the floodgates. I was utterly smitten with Antarctica and ice. I went on to visit Iceland, Greenland, Spitsbergen and again Antarctica on two more occasions.

I made the first wetland photographs on January 1, 2014, after a wonderful New Year’s Eve party at a duck camp near Morgan City, Louisiana. That day was magical, misty and mysterious. From that day I knew that the Louisiana wetlands were an under-appreciated subject and I wanted to do more work there.

In the project, you pair images from each place in a series of diptychs that function as stories about climate change, ecological balance, and the connectedness of things across time and space. How did you go about working out the pairings?

As I scoured the photographs I’d made of the wetlands and the ice fields, the pairs began to make themselves known. I had made hundreds of 4” x 6” commercial “drugstore” type prints, and I started matching pairs. Some that are in the book and exhibition are some of the first pairs and others were made as recently as a few months ago.

I taped the first groupings into a sketchbook, then I put them on my magnetic wall. For a year, I worked on them methodically.

How did you plan the images that you wanted to capture—both in terms of locations and messages that you wanted the stories to tell?

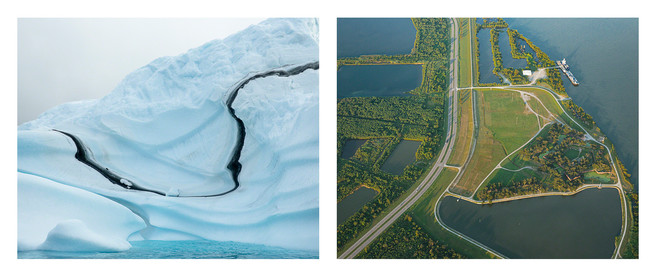

When I started shooting on location either in ice or wetlands, I was looking for a specific type of image. This iceberg is one of my favourites. I went looking for a pair and found it in.

The two locations tell the story without much interpretation. Louisiana‘s three million acres of wetlands are disappearing at the rate of about 75 square kilometres annually. Sea level rise is one of many factors. The melting of the glaciers contributes to sea-level rise.

Lamentations makes plain the crucial, threatening, and global dialogue between water in two physical states. How did this theme evolve as the key story of the project?

I am a native of Louisiana. When I was young, I went fishing with my family. We stayed on a boat in the marsh between forays into open water. My deep appreciation for the abundance, fecundity, and beauty of “my” wetlands started back then. As I became more enamoured with the places that produce ice, I realized the very close connection between the two landscapes.

For several years I sat on a national committee for conservation. As a member, I wrote two reports a year – for part of my time I reported on toxins and air quality. In researching the topic and listening to other reports, I became more and more aware of the changes that are taking place. I continue to write and present on the environment.

You have spent the past seven years on the project. Tell us more about how you managed the time on the project? What took the longest? What challenges were there?

When I photograph, I can never gauge the amount of time I have been working: Time seems to stand still.

The most significant investment was committing the financial resources to travel. Travelling for work was integral to my commercial photography in the 1980s. Because I was a location photographer, my clients were footing the bill. It was a shock to write that first check for my initial trip to Antarctica.

Perhaps my biggest challenge was learning to use my digital gear. There continues to be a learning curve, and I continue to swear I will go back to my trusty Hasselblad or 4 x 5 view camera. I am not ruling it out.

How did the project evolve? Did you have to refine the vision of what you wanted to achieve?

The pairs needed a lot of refining and repairing. Some images have up to three possible partners. At one point I wanted to maximize the number of pairs so I “speed paired” as many images as quickly as possible in about 24 hours. Most of those pairs didn’t work out. Several times I woke up and another pair had come to me in the middle of the night. The lasting work began to take shape after methodical processing. Eventually ah ha moments revealed an indelible communication between certain pairs.

What's your personal interest in this subject?

I was born in New Orleans and have lived here most of my life. When Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, it became obvious that the storm surge was caused by the loss of wetlands and barrier islands. If we hadn’t lost 25 miles of our coast, south of New Orleans, the storm surge would have been 10 feet lower: every 2.5 miles of wetlands mitigate 1 foot of storm surge.

Your project Lamentations is exhibiting at New Orleans Museum of Art. Tell us more about the exhibition. How did it come about?

Originally the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press was going to publish the book. As we were readying for publication, Susan Taylor, Director of NOMA, and Russell Lord, Curator of Photography, offered to partner with UL Press, and mount an exhibition of the images.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography?

Getting used to the enormous kit usually carried by digital folks is difficult. That first trip to Antarctica I had a 24-70mm and a 100-400mm lens; that was it. I now generally have the 24-70mm and a longer lens and, lately, a wider lens. Changing lenses is a real problem due to dust on the sensor (yes, Antarctica has a lot of dust) so it is best to have two bodies. I have started renting the second body and quite often a long lens. That is the smart way for me, since I rarely use very long lenses, and the gear seems to change so quickly. That first trip to Antarctica was the first time I had shot serious images without a tripod.

How do you create the 'look' of your images (i.e. film, post processing, etc.)?

Having shot Fuji 400 ISO Provia for so long, I try to make my images look like the images I saw printed from transparencies; less sharpening, less contrast and less saturation than the typical digital image. I did a book on colour in 1992 (Color: Natural Palettes for Painted Rooms. New York, NY: Clarkson Potter) and after testing many transparency films, this one rendered the most accurate colour to my eyes.

Tell us more about the printing and framing of the images for the exhibition. E.g. paper, size, etc

There are 52 images printed in pairs on Moab Entrada Rag Natural paper – 26 prints of pairs, each pair printed on the same piece of paper. The prints are sprayed and mounted on Dibond and then framed without glass or plastic.

There are three groups of sizes: Large (31.375 x 81.375”), Medium (19.775 x 51.075”), and Small (12.175 x either 26.775 or 31.275”), plus one extra large image (21.875 x 89.375”) and one single image (27.275 x 36.075). There are 7 small images, 15 medium images and 4 large images along with one single image in the exhibition.

In the introduction Susan Taylor, Montine McDaniel Freeman Director of NOMA says “Living in South Louisiana, we are all familiar with the reality of a rising sea level and the impact that it has begun to have on our lives. Lamentations is not NOMA’s first project to address how our relationship to water here in the Gulf region links us to a global concern, but it is the first to define through images our connection to faraway glacial regions." Through photography, are you hoping that the urgency of climate change will influence people's actions? What messages do you want people to take away from the exhibition and book?

I want the images to seduce the viewer: first, I want them to see the staggering beauty of what surrounds us, to fall in love with our Earth, to view her fragility and seeming timelessness. Second, I want them to think about why the images are in pairs, and finally, to realize that the frozen water in one frame may soon end up inundating the wetlands in our backyard.

Tell me about your favourite or most significant two or three diptychs from the book.

The first pair I used for my cover mock-ups, until the very end when we chose another image, which I love. The left is a tabular iceberg in the Weddell Sea, famous for these huge bergs. The image on the right was taken on the first day of my formal shooting of the wetlands.

Ice seemingly seeking its pair in the water field. The iceberg on the left is one of my favourites, perhaps due to its odd sense of movement. I have printed it in many ways: Platinum/palladium, salt, B&W and colour.

If one of our readers were thinking about embarking upon a large project similar to yours, what insights and learnings would you give them?

As cliché as it is to say, it is mandatory to follow your passion. The passion is what makes it work.

I don’t know when it started for me, but I lose myself in the shoot. I once had an editor that said to me that I was the only photographer he had worked with that didn’t drive him to take Prozac.

I am grateful for an outside eye to edit. I have always known this, and I could not have done the series all by myself. I am especially thankful to Russell Lord at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

For the last five years, I have been working on very large platinum/palladium prints with a master printer (due to the size). The plan is to have ten different images of icebergs.

The beautiful thing about icebergs as landscape subjects is that no matter how iconic they are, they change on a relatively constant basis. You can go to a museum or gallery or online and see an image of the “Yosemite Half Dome” and go photograph it for yourself. But you can’t do that with an image of glacial ice, it just won't be the same. I love that.

I am a “straight photographer”: what is there is there; what is not is not. Photographing the wetlands has its challenges — for instance, lack of an object like mountains in the far distance. Therefore, clouds and an interesting sky are mandatory. We have a lot of pure blue skies here in Louisiana that will rule out shooting on those days.

Generally shooting from equinox to equinox in the summer is not possible because of the sky, the heat, and the light. Being at 30 degrees north latitude, we are at the same latitude as the pyramids in Egypt. In the middle of the summer, there are no shadows; the sunlight comes straight down, and the shadows disappear – Fall and Winter are the only times to shoot. Then we go out at dawn and are generally back by 10 am.

I plan on continuing to make smaller images that will be palladium and gum prints. I want to change the tone of the prints subtly – the problem with printing icebergs with palladium is warm tonality; I am trying to shift that very slightly to cool.

I don’t feel I have been successful with printing the wetlands in platinum/palladium. Perhaps salt or another medium would be more appropriate.

I have always liked to tackle areas of photography that are a challenge to me. Some shots of birds were in the original pairs in Lamentations. They didn’t make the cut because they just weren’t as good as I wanted them to be, which prompts me to say that I might do some work with birds.

My friend and boat owner John Williams and I plan on continuing our exploration of Louisiana’s wetlands. Also, I am not finished photographing ice. Next summer I will be back in Greenland.

Exhibition

The exhibition runs from September 13, 2019 to March 8th 2020 at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Address: New Orleans Museum of Art, One Collins C. Diboll Circle, City Park, New Orleans, Louisiana 70124

Image credit

Portrait image taken by Tsuyoshi Kato hokkaido