Abundant life where you wouldn't expect it

Adam Pierzchala

Now retired, I have more time to enjoy being out with my camera looking for scenes and subjects that pique my interest, especially coastal, woodland and close-ups. Although I still have several rolls of 35mm and MF film in my freezer, I shoot almost exclusively digital now

We commonly see lichen growing on rocks, tree limbs, rotting stumps and on old wooden fences. Let’s not forget glass, metal, plastic, textiles, animal bones, rusty metal, concrete and living bark too. It should be noted that lichen grows on already old or stressed vegetation such as trees and plants, they do not actually originate the stress or a disease causing the trees etc. to die. Lichens have amazing photographic potential; they are fascinating ... and weird ... and beautiful … and rather complicated to study!

Despite their looks, lichens are neither plants nor fungi. They are unique, the result of a symbiotic relationship of organisms from up to three kingdoms, with the main partner being fungus. As Lichens of North America put it, "The lichen fungi (kingdom Fungi) cultivate partners that manufacture food by photosynthesis. Sometimes the partners are algae (kingdom Protista), other times cyanobacteria (kingdom Monera), formerly called blue-green algae. Some enterprising fungi exploit both at once."

In 2016, a new study published in Science revealed that in addition to compositing fungus and algae, at least some lichens include yeast. This yeast appears in the lichen cortex and itself contains two unrelated fungi. Lichens are definitely in a class unique to themselves, but this is not the forum to go into a lot of detail. By symbiotically bringing together two or more living organism types, more abundant life appears where normally one wouldn’t expect any. For example, I was amazed to see beautiful colourful lichens at 4000m in Colorado, where nothing else seems to grow. Despite dry summers with harsh UV-rich sunlight and bitterly cold winters with a thick layer of snow and ice, the lichens have colonised large areas of rock. Interestingly, they produce their own food through photosynthesis by their partner algae and don’t exhibit any parasitic behaviour such as feeding off the substrate on which they live. Nevertheless, lichens may absorb nutrients from their substrate and some release corrosive chemicals that slowly degrade rock into new soils.

Lichens are found everywhere from lush temperate forests to often frozen tundra, from the balmy and wet tropics to dry deserts where temperatures range from extreme heat to freezing cold.

Lichens grow only very slowly, sometimes only a few millimetres in a year. Slow growth often implies longevity and lichens are among the oldest living things on the planet. Rachel Sussman, author of "The Oldest Living Things," documents map lichens in Greenland that are estimated as being 3,000 to 5,000 years old.

Lichens have developed many different defences; as Lichens of North America write "an arsenal of more than 500 unique biochemical compounds that serve to control light exposure, repel herbivores, kill attacking microbes, and discourage competition from plants" and "Among these [biochemical compounds] are many pigments and antibiotics that have made lichens very useful to people in traditional societies." Not bad for something that is almost stationary and living in often very harsh conditions! Although lichen produces fungal spores, for lichen to reproduce the fungus and the alga must disperse together.

According to UC Berkeley however, "The most serious threat to the continued health of lichens is not predation, but the increased pollution of this century. Several studies have shown serious impacts on the growth and health of lichens resulting from factory and urban air pollution. Because some lichens are so sensitive, they are now being used to quickly and cheaply assess levels of air toxins in Europe and North America. Lichens are clearly a valuable element of the wider eco-system and many are under study for their medicinal properties. According to Ohio State University, "Research with lichens around the world is suggesting these organisms hold promise in the fight against certain cancers and viral infections, including HIV."

My interest in lichen really took off during my first visit to Iceland where I saw a fantastic variety of colours and shapes, primarily of so-called crusty but also jewel lichen. Since then, whenever I spotted lichen on a trip, I always took the opportunity to make an image, or a series of images, sometimes consciously looking for possible triptychs whenever possible.

For my close-up work I now mostly use an Olympus micro 4/3 camera with the Olympus 60mm macro lens. The fully articulated screen makes low-level close-up work far easier than lying prone trying to peer through a viewfinder or even using a right-angle attachment.

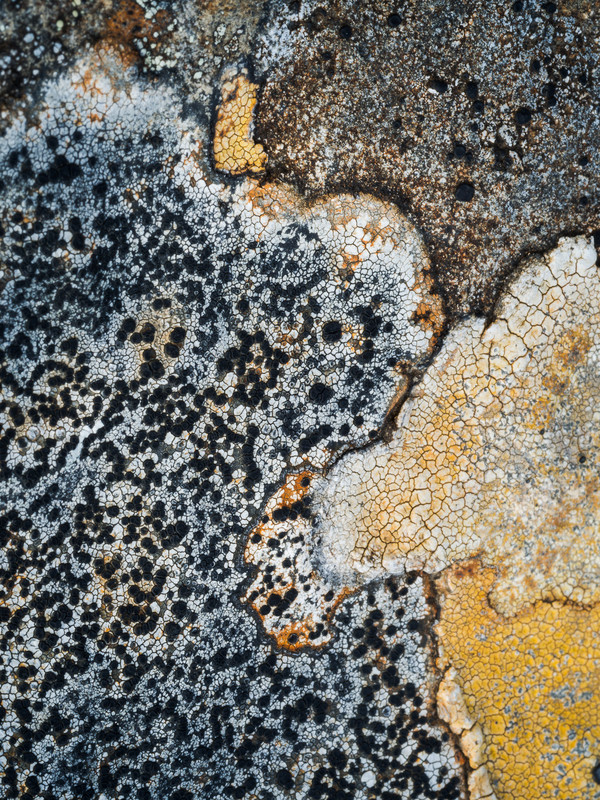

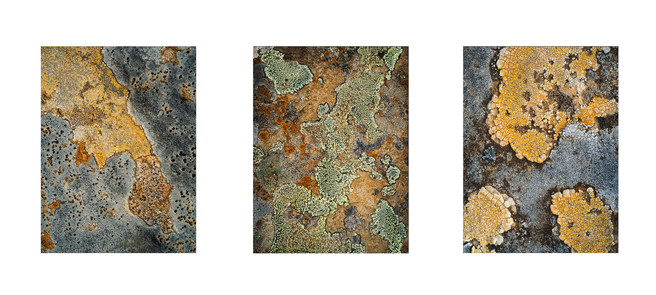

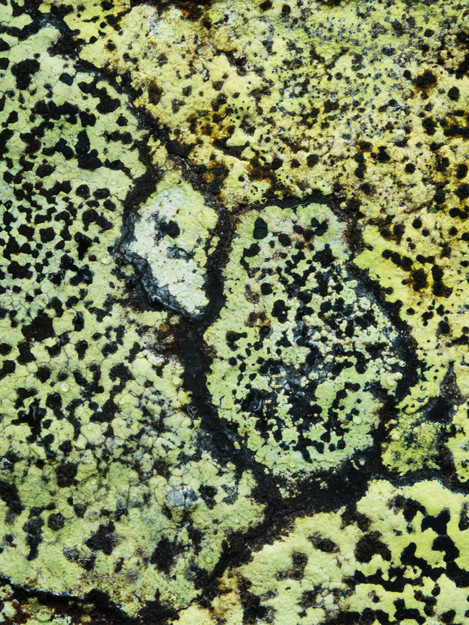

The following photos show how varied the lichen world is, yet also how the different species have similar traits across the world. The “cartographic” crusty lichens in particular exhibit quite astonishing colours and shapes. I’ve included a few photos showing the lichen in its wider habitat – after all, this magazine is about Landscape Photography!

Below I describe in a few lines about each mini-set of images I made in the different locations.

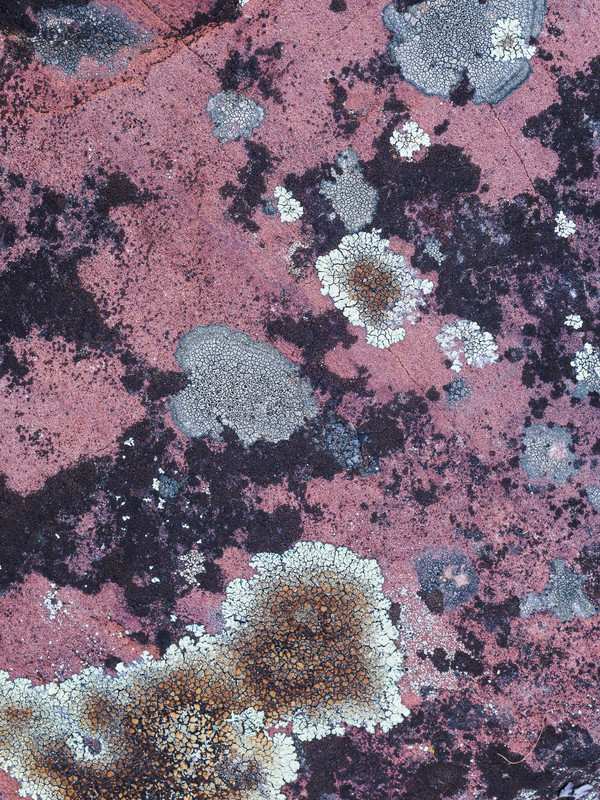

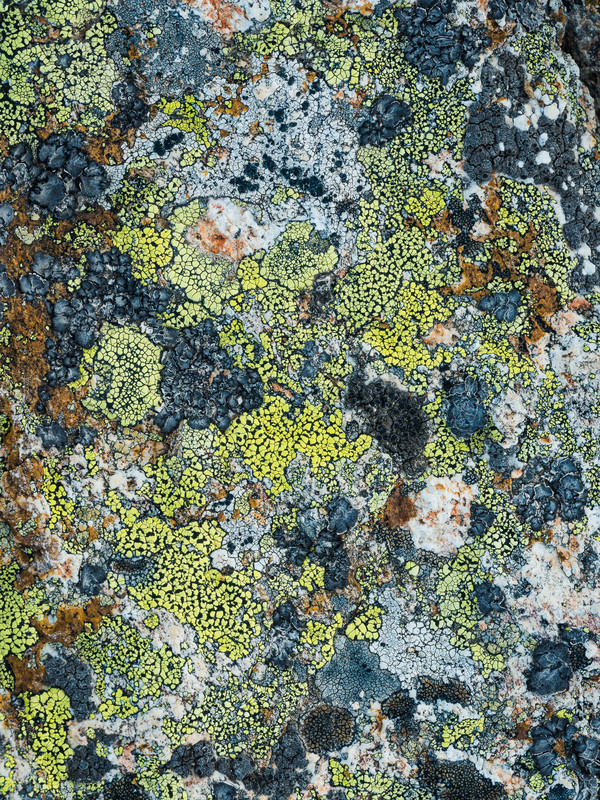

Colorado

I wasn’t looking for lichen and it didn’t occur to me that I might find some, which is a bit silly as there is plenty of substrate material for them to grow on. I suppose I was in autumn-foliage mode so when I did spot lichen on rocks this was quite a bonus. I’ve selected two very different images of crusty lichen: while photographing aspen in the Maroon Bells valley I noticed something red at the edge of a field. On closer inspection, this turned out to be maroon-red rock with mostly neutral grey-white lichen, but some ochre too. It took a while to find the right arrangement of shapes and colour, but at one point there was something reminiscent of inter-stellar clouds and I decided to make the image. The second photo is one at the top of Imogene Pass at 4000 metres above sea level. Here it was the riotous colour that attracted me and the almost chaotic abstract was an attraction in itself. The sun was shining brightly so I shaded the rock with my own shadow to soften the contrast; then in Lightroom, I slightly warmed the overall tone and further warmed specifically the bright yellow-greens to bring out their wonderful colour. This approach emphasised the colour separation, retaining a good level of blues and cyans in the shadow areas.

Dingle – Ireland

A week on the Dingle peninsula with a group of friends gave me several successful images, including lichen-covered rocks. The first image here is from Brandon Creek, a somewhat unprepossessing location at first glance, but hidden from sight at the seaward end there is a small tunnel-hole in the rock face with seawater coming through from the other side and brilliant lichens on the rocks above. The colour contrast and indeed the colours were too good to resist, so I didn’t! I tried 6 different exposures with 3-stop and 6-stop ND filters to capture movement in the sea, but as it rushed through at different speeds getting a satisfactory look proved to be a very challenging exercise.

The second image is a detail from a promontory above Clogher Beach. This area is covered with fractured rock, some sharply angled upwards and making walking across the area very difficult – a twisted ankle is a real risk. However, the photographic potential of the shapes and variety of lichen patterns is almost never-ending and with care and patience, the results made it worthwhile. I achieved several images there that I am sufficiently pleased with to print.

Faroe Islands

During a week in the Faroes with a group of photography friends, one day I had about 2 hours to explore the valley slopes at the foot of the highest mountain Slættaratindur (flat summit). After shooting a few landscapes in mono, I chanced upon some rocks with crusty lichen in glorious neon yellows and ochres, oranges and blues. Time stopped and I was totally lost in this miniature world. The shapes and patterns were rather random and I couldn’t arrive at a well-ordered composition, but the sheer colour was worth recording.

Greenland

As might be expected, the tundra and barren rocky landscapes are home to many types of lichen, some showing saturated colours spreading over large areas. Both photos I show here are from the Bear Islands in Scoresby Sound, the largest fjord system with some 300km of waterways around islands and inlets leading to glacier fronts on the mainland. The orange jewel lichen on a rock with what looks like quartz intrusion is right by the sea and must surely get submerged occasionally. The wider view is of the Rypefjord, a tributary to the main Scoresby Sound, showing how lichen has colonised quite a wide stretch of rocky outcrops.

Iceland

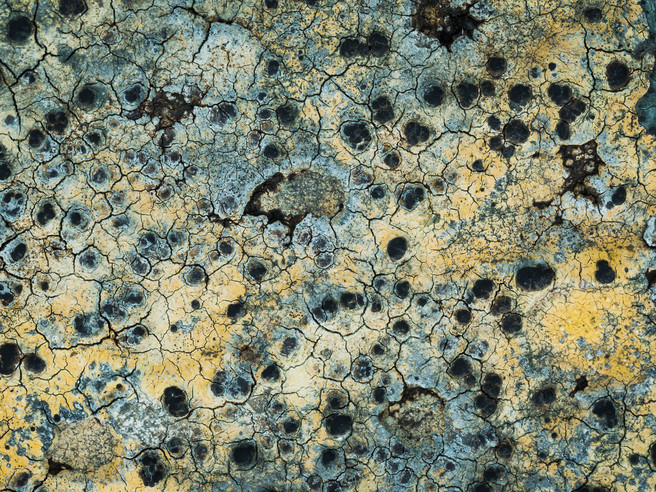

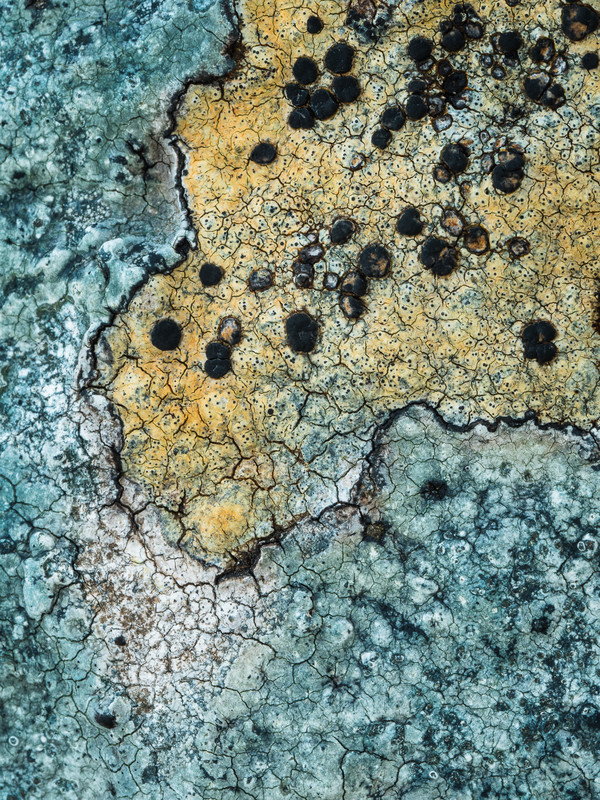

On an autumn trip, we visited Haifoss, one of Iceland’s iconic waterfalls not far from the famous Golden Triangle. After first photographing the waterfall and the valley it flows into, I still had over an hour left and decided to explore the rocks for details. Chancing on some crusty lichens, I couldn’t resist the veritable cocktail of shapes, textures and colours there, often reminiscent of aerial landscapes or cartography. Finding flat rock surfaces was quite difficult but worth the effort to try and achieve maximum depth of field.

A few days later we were in the north-east near the popular Myvatn area, where I spotted some delicate Reindeer Moss which despite its name is, in fact, a lichen. The pale pastel tendril-like form contrasts nicely with black rock and brightly coloured vegetation.

Lake District, Cumbria

With a few hours to while away before a workshop was due to start, I went walking along a path above the Little Langdale valley where I found beautiful lichen patterns on the dry stone walls. Again crusty lichen was predominant in a variety of blues, browns and bright greens. As usual, finding a series of coherent shapes was difficult and all too soon time ran out, nevertheless, I am quite pleased with what I got.

Norway, Kvaloya

The island of Kvaloya is close to Tromso, well above the Arctic Circle. Quite apart from the dramatically beautiful landscapes, there is a rich variety of flora and trees, while among the trees you can find strange mosses, fungi and of course lichens. The two photos here show some of the variety there, with crusty, foliate, and shrubby lichens and the misnamed reindeer moss, all nestling amongst grasses, real mosses and bunchberries in their brilliant red autumnal colour.

Svalbard

This orange jewel lichen was one of a larger colony on a small island in the Liefdefjorden. Situated on top of a low mound and exposed to wind, it really is astonishing that anything survived there at all. The shape reminded me of an atomic explosion, with the warm orange glow contrasting with the cold blue rock substrate.