A Trip to Switzerland

Lewis Phillips

A cultural and environmental photographer with conservation in mind all the time. Re ignited with passion since moving back to film and shooting large format.

The story of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has taken me to many destinations over the past twelve years. Living near the landscape of the Brecon Beacons has always offered the potential for regular visits, documenting what could easily be imagined as The Shire. The rolling hills of the Beacons, so familiar to Tolkien during his childhood, and the musical tones of the Welsh language may well have influenced many of the names and places we now know in Middle-earth. You can read my previous articles on Tolkein are: Tolkien’s Shire in Lord Of The Rings & Walking in the Shadow of Middle Earth.

Later in life, Tolkien travelled to Italy, a country he adored for its culture, food, and the dramatic topography of its landscape. The jagged peaks of South Tyrol and the Dolomites seem to echo through the mountains of Middle-earth. In Tolkien’s time, what is now northern Italy — possibly the inspiration for Mordor — would have been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, later reshaped by the tides of European history.

I have spent many hours walking through these landscapes, imagining what Frodo might have felt as he struggled to return the Ring to the mountain where it was forged — or what it would be like to plant crops in the Shire, drink fine ales, and smoke a pipe beneath a broad-leaved tree.

As I’ve mentioned in my previous articles on this long journey, Tolkien’s world can sometimes become political territory. He is revered worldwide, and his work is taken with great seriousness — occasionally too seriously. Over the years, I’ve heard heated debates among academics, each trying to prove that their interpretation of Tolkien’s travels and inspirations is the correct one. I’ve even heard a few bitter words exchanged about whose “Middle-earth” is the true one.

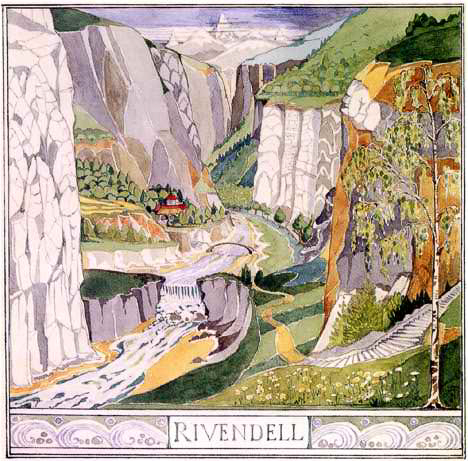

However, there is one place where argument seems unnecessary, a location backed by Tolkien’s own words and sketches: Rivendell, or as it is known in the real world, Lauterbrunnen in the Swiss Alps.

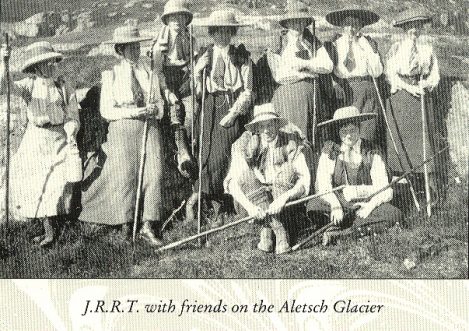

During the year 1911, when Tolkien was just 19 years old, he was invited to join a group walking in the Swiss Alps. The trip was initiated by the Brookes-Smith family, who had visited the region on a number of occasions before the First World War. Tolkien, along with his aunt and others, spent a few weeks in July and August travelling on foot through what we now know as the Misty Mountains. The Swiss Alps were his first experience of the heady heights of a serious mountain range. It is clear from his documented letters that this landscape inspired the mountainous peaks of Middle-earth, including Rivendell.

Rivendell, or Imladris, was an Elven outpost in the Misty Mountains on the eastern edge of Eriador. Due to its location, it was called the Last Homely House from the point of view of a traveller going eastward into the Misty Mountains and Wilderland, and the First Homely House for those returning from the wilds to the civilised lands of Eriador in the west.

It was established by Elrond in the Second Age, year 1697, as a refuge from Sauron after the fall of Eregion. It remained Elrond’s seat throughout the rest of the Second Age and all the way into the end of the Third Age, when he finally took the White Ship to Valinor. Rivendell maintained a strong alliance with the Kings of Arnor, and after the fall of Arthedain it became a sanctuary for the Rangers of the North and the Heirs of Isildur.

If I ever dedicate a full book to my travels in search of Middle-earth’s real-world counterparts, this is one place that must be included. My visit to Switzerland was originally for a lecture at a college in the medieval town of Fribourg, but Lauterbrunnen was only a three-hour drive away. I couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit what is widely accepted in Tolkien scholarship as the home of the Elves.

My research started by revisiting the maps of the tour that had been documented. I also contacted the Tolkien Estate for information on any writings or artwork created after his visit. I then planned the more remote drive to the region, documenting my journey along the way.

After a brief stay in Fribourg, I set off across the lofty hills — what the Swiss modestly call hills, though at over a thousand metres they would be considered mountains back in the UK. Driving through thick fog, I could hear the soft clanging of cowbells in the distance. It was November; the leaves were still clinging to the trees, glowing with late-season colour after a gentle autumn.

As I descended toward the plains near Thun, the fog began to lift, revealing the Alps towering over the landscape ahead. The road followed the shoreline toward Interlaken, sunlight now breaking through as signs for Grindelwald appeared. I was in the shadows of the mountains — vast, stony giants blocking the sun, their sheer faces gleaming with cold light.

The name Grindelwald reminded me of places not far from my own home in Wales, though here the landscape was on a grander scale. Turning off the main road, I drove deeper into the valley — into what felt unmistakably like Rivendell.

One of the things that strikes any visitor to Switzerland is how efficiently everything runs. The roads are smooth and orderly, trains seem to appear from nowhere, and infrastructure is woven cleverly into the landscape. Yet despite this sense of calm organisation, I felt a strange unease as the road narrowed and the valley walls rose higher around me — sheer rock faces climbing into the mist, silver birches clinging to the slopes, deep shadows pooling between them.

Also, another uneasy part of travelling to this destination was the sheer number of people. The roads were busy, walkers streamed in every direction, and helicopters flew in and out above the valley — reminding me of air traffic departing from London Gatwick. Surely this would not have been the case when Tolkien visited as a young man. In his time, Lauterbrunnen must have been a place of quiet isolation, where the only sounds were the waterfalls, the wind through the trees, and perhaps the scratch of his pen in a notebook.

Then, rounding a bend, I passed the sign for Lauterbrunnen. The valley opened up before me — waterfalls spilling down the cliffs, chalets tucked among trees, and the sound of water and wind mingling in the air. There was no mistaking it. I had arrived in Rivendell.