Creating something other than an objective facsimile

Graham Cook

In retirement, Graham Cook is a painter of portraits and a free-thinking abstract photographer with determination to retain an openness of mind and capacity for wonderment.

Once I'd 'friended' Graham Cook on Facebook it became quickly noticeable that a new thread of images were inhabiting my stream. These weren't the usual classic landscape and not even what you would expect from a photographer making more intimate images. These were truly abstract extractions of the world but still with a solid link with reality. As it became quite clear that Graham had quite a unique way of looking at the landscape I thought I'd ask him to write a few words about what he does. After a little tussle with the "but it's not landscape" he finally accepted, and for that I'm grateful and I hope you will be too.

Photographically I consider myself largely anonymous, with only a handful of respected friends on Facebook acting as my photographic ‘community’. Most of my output is eclectic and highly personal. But the invitation to write something about my work has meant stopping to consider what it is I do and why it is I’m doing it.

I make no apologies for leaning on others to help articulate what goes on behind my eyes and I can’t pretend that this will blossom into an article of any intellectual or technical merit – in any event that just isn’t me – but it may offer some insight into the passion and motivation behind what I do and where I come from.

I’ve never had a problem with ‘creating’ or thinking differently. In fact, the problem sometimes has been controlling it and adding purpose, as Primary school reports trenchantly imply. But creativity has many spurs and as my eyes became more panoramic and receptive the desire to take advantage of this ‘landscape’ became overwhelming.

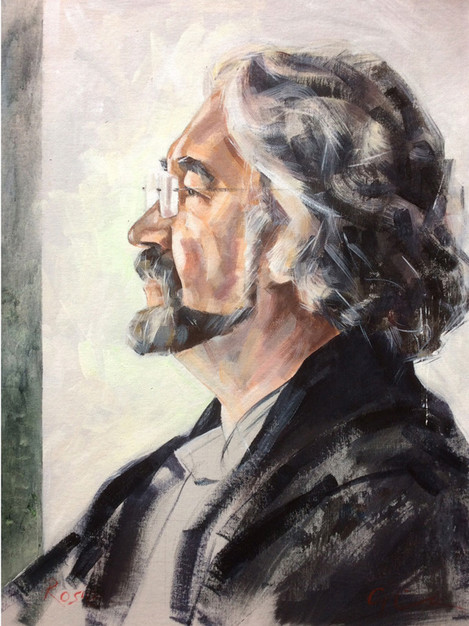

During my first weeks at Art College, as a relatively shy individual, I felt intimidated by other students. However, in a free-thinking non-judgemental environment I soon discovered that a lively imagination, coupled with raw talent and supple vision meant as much if not more than myopic academia. Although not a pre-requisite for the graphics course, what also set me apart was a natural talent for drawing and painting but really, all that meant was a deep frustration at not being able to attend the fine art course.

Consequently, I never found answers to the questions I kept asking myself about the true value of my painting ability. I was never able to develop a style or still the persistent voice inside me.

Although photography was an important element at art college and during my 45 years as a designer, I’d never intended it to become a major part of my life or have much of an influence on my creative output. The plan for retirement was to satisfy those finer, more personal artistic ambitions that had remained frustrated since college and had played second fiddle to a profession spent serving largely untutored commercial and corporate audiences.

So photography was introduced simply as a strategy, a means to an artistic end, to help rewire my mind allowing less predictable thinking regarding colour, form and composition in preparation for the genuine ‘artistic’ task of painting. Little did I know photography was to become an end in itself.

But why in the landscape space? On reflection, the starting point for this journey was greatly influenced by David Noble*, a freelance designer working with me during the mid 1980’s. After attending a series of photographic workshops with Nicholas Sinclair, Thomas Cooper and Paul Hill and a summer school at the University of Derby where he met John Blakemore and Martin Parr, David introduced me to a full range of possibilities associated with photography. Now Edward Weston, Walker Evans, Paul Strand and Minor White became a regular part of our general creative discussions.

Roughly 25 years later, a chance meeting with Charlie Waite at the Oxo Tower Gallery reinforced the view that landscape photography had much to offer. What followed were the naïve fumbling years of my photographic adolescence. Through practice and the odd single day workshop (beech avenues and National Trust gardens spring to mind) I began to build the skills and broader knowledge necessary to progress.

My first David Ward and Joe Cornish masterclass in Cornwall was cathartic. Mixing with a group of highly talented participants was both inspiring and intimidating. I’d never doubted my ability to do ‘art’ and have an unshakeable inner confidence but here, out of my comfort zone, my photographic confidence was indeed shaken. By the end of the week I was the only one not to show prints. I felt I’d let myself down. But all was not lost.

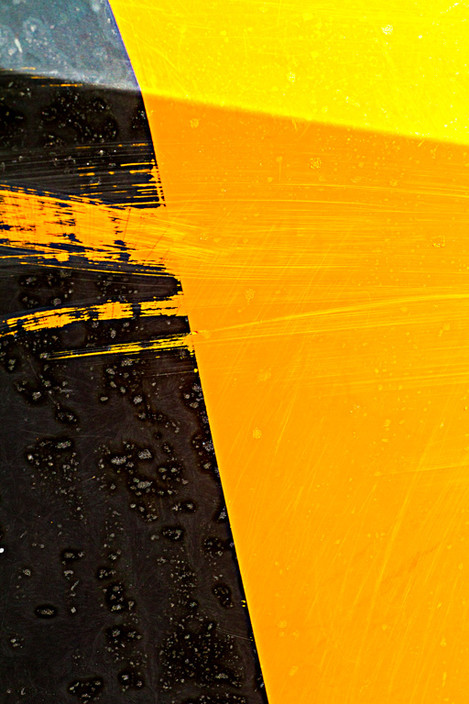

Although conventional landscapes formed most of the early work I found them difficult to value accurately and simply recording superficial impressions became progressively unrewarding. It was so difficult getting what I was about into the image. However, there was light at the end of this particular tunnel. To be precise, it was light striking the angular hull of a fishing boat that opened my eyes to the possibility for an image to be something other than merely an objective facsimile.

That was December 2013 and since then David and Joe have been integral in helping me to pursue and develop my ‘voice’. There are of course many many others who have directly influenced the way I respond to image making. It’s almost unfair to single out individuals but a supporting cast would be led by Valda Bailey, Paul Kenny, Mark Littlejohn and the highly considered work and writing of Guy Tal. I just love artists who ask questions of me and force me to question how I see. Artists who show humility and don’t follow ‘styles’ or ‘trends’ but remain true to their own beliefs whilst appreciating photography in the wider context of ‘art’.

Nearly all art shares the goal of communicating a message to an audience but the style in which that message is communicated differs greatly. If I think about it, what I’m trying to develop is a voice that describes the natural world in a distilled and simplified form. Yes, one can enjoy a pint of bitter from the wood but a nip of fine whisky or cognac is a different, more intense experience. Is one better than the other? It could be argued so but really they are just different. What is essential to the taste is the intent and the passion behind the process of creation.

For me photography is not an obsession but creating is. This obsessive voice within, nagging and prompting, driving my eyes to interpret and reinterpret the world. I believe the landscape can be reborn, that it also exists in a kind of parallel world, just as real but revealing itself using a different visual language. I consciously try to create images that provoke and ask questions of the viewer. I may not like the answer but the viewer is as much a part of the process as I am. In common with my paintings, I don’t want to be passive or absent from my work and I don’t want to produce work that provides all the answers.

Writing this has forced me to consider whether or not I do actually take ‘abstracts’. If we examine the word abstract, and for this I turn to the Tate’s glossary of art terms, it states ‘Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect’. But isn’t what I do ‘an accurate depiction of a visual reality?’

Everything I’ve done creatively, from a life in short trousers to retirement and a life in shorts, has felt instinctive. Feeding this has been an open mind and a surreal and somewhat irreverent imagination. I’m almost totally driven by feel, by curiosity and an unlikely connection with the subject. When I identify an image, instinctively I respond, intuitively knowing it’s right. I spot an opportunity, often in the most unremarkable circumstances, and immediately zone in. This moment is uncompromising and a point when I try not to let an overreliance on technical mastery spoil natural interpretation. As David Ward has often stated, ‘Craft is important but it’s not paramount; vision is’.

It’s frequently said that we’re the sum total of all the parts of our life, where a synthesis of ideas, influences and experiences make a whole. How those ‘parts’ or experiences affect how much we see, varies considerably but this essential formative process operates subconsciously. For me it’s a vital element of the process of seeing. I take inspiration from a wide range of artistic and creative sources and much of my work has a narrative fed by artists – anything from Blake to Rackham, Palmer to Rothko. I retain an infants’ psyche and reference works as varied as Alice in Wonderland to Just William, from Tin Tin to Rag, Tag and Bobtail.

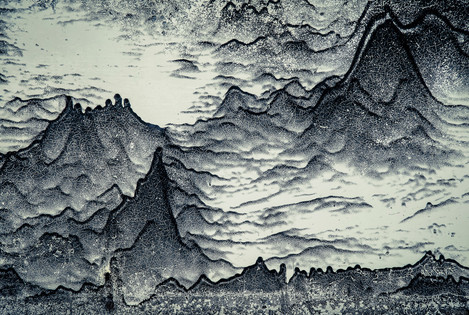

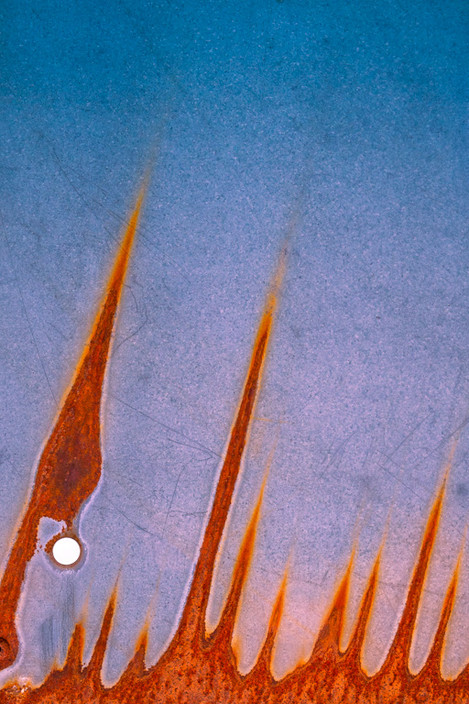

Combined with an appreciation of design, and an endless fascination in the ability of nature to reclaim ground once lost to the hand of man, I try to allow my ‘abstract’ forms reveal an alternative beauty to be found in the patina and continuum of life. As Paul Klee said: ‘the intention is not to reflect the visible, but to make visible.’ I try to challenge assumptions, to penetrate the world, both natural and man-made, with an eye in such a way that the inner structure of reality is revealed.

Why photograph the obvious when fragments act as shorthand to the life of an object? Scratches and paint drips, the flow of discolouration from exposure to the elements often say all you need to know – your mind can do the rest. I allow myself to think how much beauty and ambiguity lies between the surface of erosion and decay. To me, it’s not the scruffy ugliness of crudely painted fibre-glass filler or sun melted tar, it’s the attraction of what it could become, how it can re-surface as something else, something visually intriguing and graphically pleasing, taking one beyond the ordinary range of perception.

To walk round the back streets of any town or city offers a keen eye real opportunity to turn the functional, the ordinary, the used, the second-hand, into something more remarkable. Freeing objects from their true association. Similarly, to travel through the natural world where intricate shapes and rich textures, lend grandeur to the natural forces at work, yet captured in a particular way, can defy obvious interpretation. The erosion of sandstone or fractured granite reveal almost lyrical abstract design. These austere, organic shapes have a constructivist feel, with simple forms offering aesthetic potential.

However, I wouldn’t choose to live in a world of total abstraction, devoid of beauty, emotion and feeling as the chords forming the soundtrack of my life are far from discordant. I think Kandinsky was right in recognising that one must always be mindful of the danger of abstract painting becoming ‘mere geometric decoration’ and this is possibly even more relevant with ‘abstract’ photography. Therefore, part of my battle is to make seemingly inaccessible images accessible. Images that repay repeated visits.

I want to find a beauty in the obscure or perhaps try to extract beauty from the ordinary. I understand that beauty is a combination of qualities held very much in the eye of the beholder, yet fresh resource and the changing conditions of visual language in modern life gives legitimacy to alternative means of expression. What passes for beauty continues to be reinterpreted as we grow a different understanding of reality and a greater tolerance towards art and artists.

As someone who responds to creative challenges by feel, the deeper technical facets of photography are something of a stranger. Although important, I’m happy to avoid more detailed technical discussion in preference for dreaming. My camera bag is rarely if ever refreshed, and the 5d III only seems to make an appearance on workshops – roughly five times a year. This means I’m constantly trying to remind myself of its functions so the first day of any workshop is often awkward and unproductive.

Apart from a Fuji XE-1 the majority of the images I share are taken using the iPhone. It is my sketchpad. It allows me spontaneity. There are occasions when my eye is so keenly tuned that only the convenience of the iPhone allows me to meet demand. I’m also a big fan of cropping and see it as a much maligned creative tool. This may be a legacy of my design career, but I crop as I see fit. There is an intention to live by the mantra of the need ‘to get it right in frame’ but is it not possible to improve and encourage creative growth through judicious pruning?

My ideal environment for post-capture editing is Lightroom. Used responsibly, it has become a very creative and liberating part of the process. It’s quite remarkable how one can resuscitate discarded images and rescue perfectly good files that were taken with intent but that lacked the presence to impress during initial reviewing. I’m also not shy to use the dodge and burn facility in Photoshop as I feel I’m putting my hands directly into the image and influencing outcome. This has a painterly quality about it. What is perhaps more interesting is how I use Lightroom to advance understanding of my painting. Photographing an artwork as I progress, I can locally adjust things such as colour intensity and contrast. Essentially it identifies areas where I’ve been too timid, giving an insight into where improvements can be made.

There’s little difference in terms of the principles of composition between painting and photography but how those principles are applied is very different. When I paint I do so facing a blank canvas but the camera viewfinder is the complete opposite. A painter can enjoy the freedom of placing an object where he or she chooses yet the photographer must work harder to isolate elements within a crowded frame in order to bring agreeable composition to a well-balanced work of art.

I can lose myself when I photograph but I’m totally absorbed when I paint. Light may be of equal importance but time has a different relevance. The tactile and direct nature of pushing paint around has greater resonance and I find the whole process more inwardly satisfying since I feel there’s more of me in a painting. However, creatively I find little difference. I’m excited in equal measure to reach a new level of accomplishment in painting as I am in identifying a unique capture in photography.

Yet there’s a wonderful irony in the fact that I’m able to be freer with photography than with painting. I seem to have fewer hard wired preconceptions about what stands for photographic convention yet I’ve always been ‘photographic’ in the way I draw and as such, I struggle to realise painted works as freely and expressively as photography. It was fascinating to discover that at a recent exhibition held in partnership with a landscape painter friend, my ‘abstract’ photographs were considered more painterly than his ‘photographic’ paintings!

As you may imagine, there is an on-going battle between pixels and paint and the dilemma for me is the constant flick flacking from one medium to the other. The ambition to master both may be beyond me. I may end up being the proverbial ‘Jack of all Trades’. However, I derive satisfaction from the progress I’ve made so far and photography and painting are currently happy bedfellows. But my main enemy is time. After sacrificing so much in favour of being relatively successful professionally I am, at 66, fast-tracking to prove I’m the artist I always thought I could be.

If I have an ambition it’s to pull the two disciplines of photography and painting closer together. Quite how this will manifest itself is the exciting part. Regardless of the outcome or how successful my work is judged to be it’s for others to determine its relevance. I’ll be content to satisfy and meet my own expectation and will remain predictably unpredictable. What I do know is that I now look at the world in a much more probing and provocative manner and in that respect my life continues to be refreshed and enriched…and for that I have, in part, to thank landscape photography and those generous and open-minded practitioners who have advised, influenced and motivated me to just be me and not to say ‘why?’ but ‘why not?’

*David gained BA(Hons) Photographic Studies (First Class) at the University of Derby and teaches BA(Hons) Photography Award at Staffordshire University.

- Velocity

- Surface tension

- Cornish trawler

- After Wallis

- Evocation

- Ingression

- Multiplicity

- Little Langdale trough

- Tate tea room

- Orange sunset

- Reception

- Letterbox

- Stephen

- Kaleidoscopic rust

- Skegness storm

- Vexatious lizard

- Target practice

- Turner Contemporary

- Damp dustbin

- Jessica