A Book Review

Colin Prior

In a career spanning thirty-five years, Colin Prior photographs capture sublime moments of light and land, which are the result of meticulous planning and preparation and often take years to achieve. Prior is a photographer who seeks out patterns in the landscape and the hidden links between reality and the imagination.

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

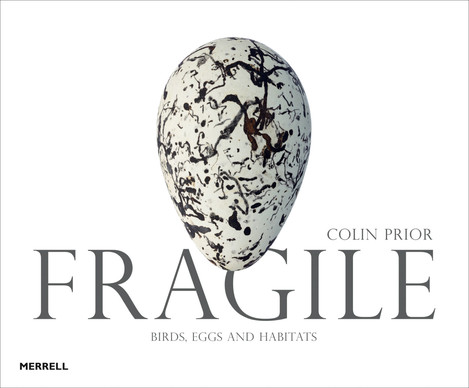

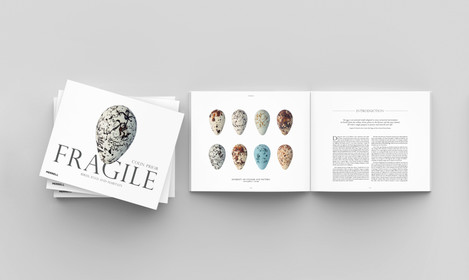

If you were to take a guess at the topic of Colin Prior’s new book project you may be forgiven for thinking it would be documenting a part of the Alps, working on Scottish plateaus or perhaps portraying the sublimity of the Himalayas (actually, I think the Himalayas will be the next one). What you probably wouldn’t guess is that it’s a book on eggs.

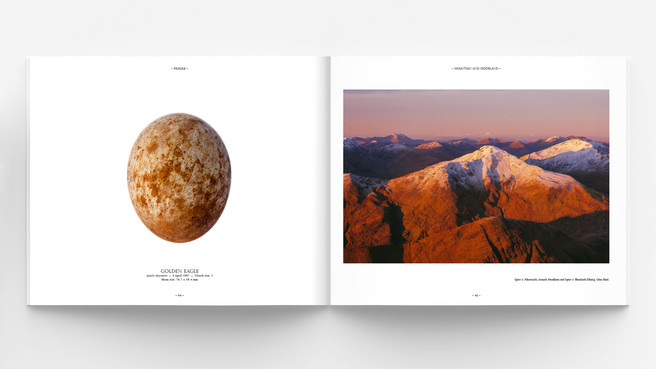

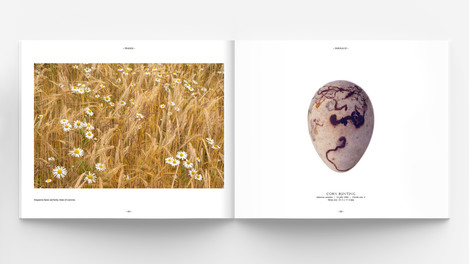

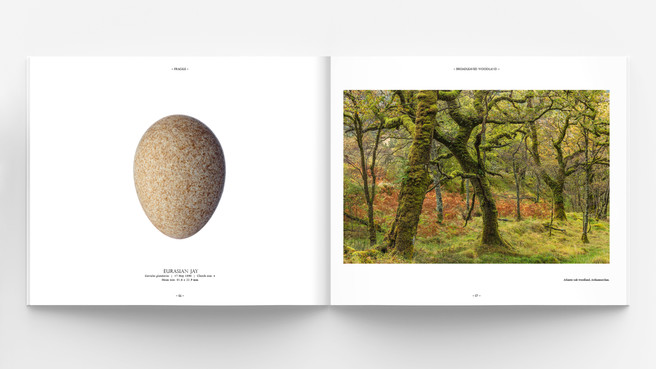

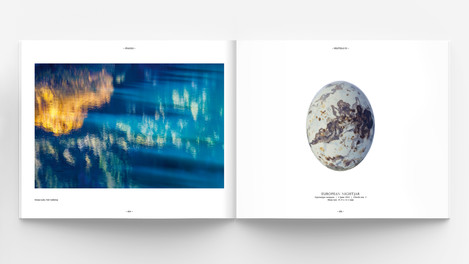

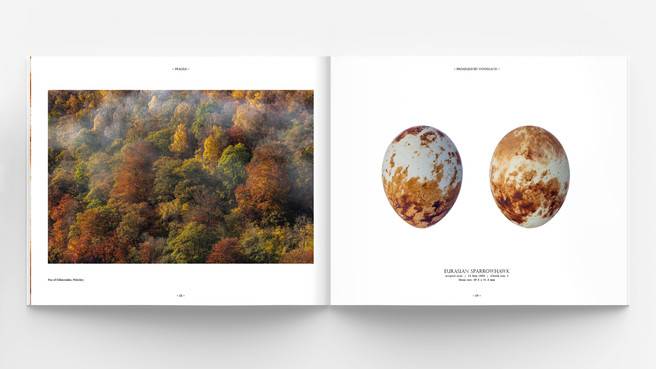

Yes, you read that right, this review will be about a Colin Prior book on bird eggs of Scotland. And yet, as surprising as this sounds, it isn’t as random as it first appears. You see, Colin isn’t just passionate about the Scottish landscape, he’s also passionate about the wildlife that lives within it and it is this passion that sparked an idea. What makes the project particularly interesting, and relevant, for us is that for each of the exquisitely captured photographs of bird eggs, there is an associated landscape photograph that represents the habitat in which the egg would be found and has been paired to also give an aesthetic complement.

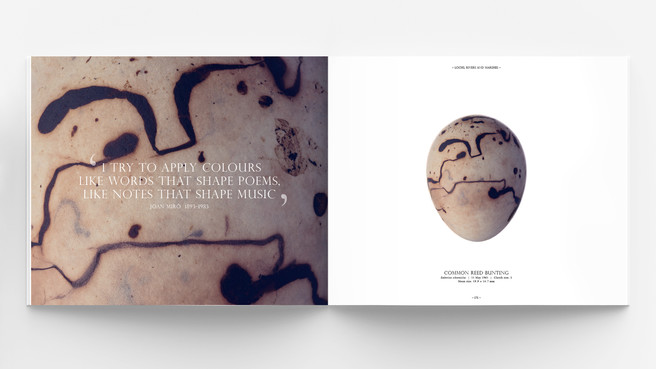

The result is a series of pairs of images that deliver much more than each would on their own. The book hits a very nice balance between just enough information in its preliminary essays to give scientific and environmental context but letting these pairs of photographs speak for themselves on their artistic merit. The patterns of camouflage on the eggs are constantly intriguing and the photographs of the landscape strike a good balance between representing location, portraying patterns and textures of the environment and bringing Colin’s sense of the aesthetic to each so that they may be enjoyed in isolation and in its pair, neither overwhelming the other.

On returning to this book repeatedly over the last weeks, I have been reminded that the sense of landscape photography producing individual ‘hero’ pictures is one that really only represents a single aspect of its utility. When used as part of a larger project, one that informs, intrigues and entertains the viewer at the same time, it brings a whole new perspective. This book is a great example of this and I would love to see more like it.

We got in touch with Colin to ask him a few questions about the project.

How did you come up with the idea for the project and what were your thoughts on how to present it?

The idea for Fragile began over twelve years ago and was a natural progression of my landscape work. I had spent the last 25 years shooting with the panoramic format and was ready to move on – I felt I had said what I wanted to say with that format and found that it had literally become a creative straitjacket. I wondered if there was a way in which I could fuse my passion for birds with that of the landscape without having to photograph birds themselves and was aware of the innate beauty of birds’ eggs. I was keen to create a body of work that was beyond views and was underpinned with an environmental message. Birds’ eggs offered something new and visually exciting which I felt people would be intrinsically drawn to and which would act as a metaphor to highlight the demise of wild bird populations throughout the UK.

How many of the images in the book were taken specifically for the project rather than accessing your extensive back catalogue?

Previously, when I was predominantly photographing from elevated mountain viewpoints, I had built up a list of undisturbed locations that I had either walked or driven through, en route and it had been my intention to return to these when the time was right – it was in these locations where most of the new images were created. Accordingly, there are not more than a couple of images used from my archive - they have all been photographed specifically for the book. With some locations, I needed to return at a different time of the year to achieve the colours I needed to match a specific egg – the dominant colour of the egg was ultimately my starting point and it wasn’t without challenges to create both a synergy between egg and habitat and diversity at the same time.

What makes eggs so visually fascinating is their shape, their colour and their patterns. In our early design concepts, my designer had chosen to present the eggs in a grey (80% white) box as she felt that the white page made the egg feel like a cut-out, which is not the case. I wasn’t convinced and wanted white space between the egg and the habitat, but it took me some time to realise why I didn’t like the grey box. One evening, I was looking at the PDF and became aware that, instead of my eye exploring the enigmatic shape of the egg, it was following the edges of the grey box, something, I concluded, that was not an attribute, so we lost the grey background and went with pure white.

I know you’re very familiar with many of the birds included but did you have to do much extra research into habitat and behaviour in order to complete the project? Did this research change your mind about what images to include?

Research was crucial to the project – it was important that I was photographing habitats that were, in fact, areas where each specific bird bred and to this end I liaised with many experts in their fields, often via my contacts at the RSPB and NatureScot and with various stalkers and gillies that I have befriended over the years. Often their advice refocussed my efforts in a different area – I recall struggling with the greenshank’s habitat at Forsinard in the Flow Country – it’s a largely flat and featureless blanket bog and not easy to create a landscape image that has sufficient interest. Professor Des Thomson, who wrote the opening essay of the book, confirmed that greenshank nest in the Flowerdale Forest in the heart of Torridon which gave me a little bit more to work with. Another species, the nightjar, which nests in Scotland in tiny numbers is found only within a very specific range, so I had to concentrate my efforts in a geographically small area which proved to be very challenging – in the end, it was a change of approach that finally led to success.

The process of photographing the eggs is a strange mix of technical/scientific and aesthetic. What choices were involved in how to portray the eggs beyond mere technical accuracy of colour and focus?

Once the eggs were on the table, the stacking unit would be activated, and we would be shooting anything between 40-80 images depending on the egg size. The lighting was crucial to the photography and I had already established how I would light the eggs before setting up in the museum. Images were collated and then stacked in Helicon Focus.

One of the biggest historic threats to wild birds was DDT and the book provides an excellent background on this. What do you see as the biggest current threat?

The story of eggs and the crucial role they played in establishing the devastating effects of DDT is well documented. Throughout my lifetime, I have witnessed, first hand, the demise of wild bird species, not only from my former family home where I was brought up, but from many other areas with which I am intimately familiar. The trends over the last 50 years are not encouraging with species such as lapwing, curlew and starling down by around 60% - many others show declines of anything between 20-40% and this is being driven largely by changes of land use and habitat loss. Large scale housing and retail developments can have catastrophic effects of local bird populations, particularly if the green belt has been encroached and increasingly, climate change is beginning to compound problems. It is difficult to see how this situation can improve and as more and more people are using the countryside recreationally, the ramifications for wildlife are not good. Long term, I see this loss of biodiversity accelerating as we continue to encroach and fragment the land areas on which wildlife depends. Despite this, Fragile grew from my sense of wonder of the natural world and it is my hope that you can share in that wonder too.

You can purchase signed copies of Colin Prior's "Fragile" at his website for £35. Click here to access the product page directly.