Can we as landscape photographers take images devoid of an understanding of the history and significance of a given place?

Geoff Pearman

Geoff Pearman is lives in Dunedin New Zealand. Over the past 18 months he has rekindled a passion for abstract photography. He loves big landscapes and creating landscape images using camera movement during relatively long exposures. More recently he has been playing with the musical composition idea of fugue to create re-imagined landscapes.

I am privileged to live in a country that has many spectacular landscapes that entice the photographer to get out their camera, set up a tripod and capture stunning images.

I love open spaces, the mountains and rolling hills, lakes, rivers and coastline. Landscapes are in my DNA. But before I explore the question of why I create the images I do, I want to delve into a question that has been exercising me, what is a landscape. I was given a copy of Masters of Landscape Photography (2017) for Christmas. Robert MacFarlane’s foreword resonated “… For far too long we have been content with an understanding of “landscape” as a passive backdrop to human life: an aesthetic surface that we are “on” but not “in”…. I have argued that we need a vastly more dynamic understanding of “landscape” as a force that shapes us and scrapes us…”

The concept of “landscape”, as far as I can establish, was a cultural import to Aotearoa - New Zealand, from Europe. Colonialists and early settlers viewed the land in different ways depending on their reason for being here. The early scientists recorded natural features, surveyors made maps, settlers saw productive farmland and promoters of tourism the pictorial scene that would entice.

And so pictorial representations of the landscape, be it a painting or photograph of the Fiords, the Southern Alps, the thermal regions of central North Island, or Maori as an indigenous people became the subjects used to portray New Zealand to the world.

It was not just tourism marketers and professional photographers who created the stunning landscape photos but also amateur photographers. A historian of photography in New Zealand observed that Pictorialism found its most enthusiastic adherents within the camera clubs. A style of landscape photography that became well established, just walk into any bookshop, travel agent or camera club. Of late I have become increasingly dissatisfied with this style of landscape photography. While some images are absolute masterpieces and draw me in, for some reason many don’t engage me emotionally. Maybe that is part of my journey.

I am coming to realise that when I pick up my camera and engage in the act of creating a landscape image, I bring everything about who I am, my history, culture, values, emotions, world view etc. to the process. Landscape photographs are not to be captured or taken; they are created. As one social theorist nicely puts it

This raises some interesting questions for me. Am I just an observer with camera in hand who is there to spot, frame and capture what I see through the window of the lens? Or am I a participant who through the act of engaging with what I see creates a landscape photograph and, in the process, says something about the way in which I am experiencing the world?

I am finding that I create some of my better images when I slow down, soak in the environment, feel the atmosphere and slowly explore the landforms. If I have had the time to develop an understanding of the history, culture and significance of a given place it helps. Which raises an interesting question. Can we as landscape photographers take images devoid of an understanding of the history and significance of a given place? Will understanding something of the geology of a mountain range, or the cultural significance of a location to the indigenous people or the belief systems of those who built and worship in a given cathedral or shrine enhance and find expression in the images I create? When I have raised these questions with some photographers, I have encountered a blank look. After all isn’t a good photo all about location, technique, camera settings, the time of day, post processing etc.

In the Maori creation story, it was Tãne the god of the forest who separated Earth and Sky allowing light to shine on the earth so freeing the world from darkness. This whakatoki (proverb) is often used as a metaphor for the attainment of knowledge or enlightenment.

I personally have a discomfort with the pursuit of “trophy” images. It seems everyone with a camera (and that is most people) who visit the South Island of New Zealand has to have a photo of the Church of the Good Shepherd or the Wanaka Tree. The “detached photographer” dropping by to “gaze and capture” and post yet another trophy or maybe if a little more serious take a prize-winning photo. While once this is what drove me, I now want to engage and immerse myself more fully in the environment and play with ideas.

So why my love of landscapes, big wide spaces? And why have I discovered more recently a passion for abstract landscapes? Questions I am still puzzling, with the search no doubt seeping through in my photography.

I was raised on a farm north of Auckland in New Zealand. A farm hewn out of bush by my great grandfather an immigrant who came to New Zealand from Walkern in Hertfordshire as part of the non-conformist Albertland settlement movement. As a child and into adolescence I spent a great deal of time wandering the rolling farmland, climbing the hills and exploring the gully’s and creeks that ran through our farm. Fishing excursions to the east coast sandy beaches and rocky headlands gave me a love of the coastal areas.

I love big wide expanses and have also recognised that I need to live where I can see an edge, be it a view of the hills or a coastline. While I love the deserts of Australia and central Asia, and the big cities, I couldn’t live there, I need an edge.

Since childhood, I have sporadically photographed places visited. I recall being given a Box Brownie by my parents at age 10 and carefully saving my pocket money to develop the photos I took when on holiday. Soon after marrying in the early 1970’s, we moved from New Zealand to Sydney for 3 years. I invested in a Kodak Instamatic and produced trays of slides as we explored a new country.

Fast forward and with little photographic interest in the intervening years, it was the late 1990’s before I picked up the camera again. I was running the Continuing Education programme at the University of Canterbury with access to some amazing photography teachers and with my wife made the most of the opportunity to learn. As part of my work, I was invited to the Antarctic, given a crash course in polar photography, loaned a Canon SLR and supplied with heaps of film. Following this trip, I actively pursued landscape photography while my wife started her journey into abstract as an early adopter of Lensbaby.

It was the early 2000’s when I discovered abstract photography. Meeting Ken Ball from Australia was somewhat fortuitous as I discovered from him that by deliberately moving my camera, I could produce impressionistic images. I recall a photoshoot in rural NSW Australia with Ken and a friend from the USA who to this day is no doubt still shaking his head completely mystified as to why we would want to move our cameras about and smear Vaseline on filters to create “blurry photos”.

I put that early foray into the abstract aside as we travelled to exotic locations; Samarkand, Lhasa, Bagan, Xian, Alaska, Hudson Bay, the USA, Japan and the Northern Territory of Australia. Amazing landscapes and cultures all inviting me to document what I was seeing.

Twenty nineteen was the watershed year. My wife, with her ongoing passion for abstract photography, wanted to attend an abstract photography workshop run by Len Metcalf and Shirley Steel in Australia. I went along still wedded to “straight” images of the landscape. I had no choice but to start experimenting with the different techniques taught. I was hooked, and my self-image as a photographer transformed. The seminal moment was when I realised that every time I pressed the shutter button I had the opportunity as an “artist” to create a work of art that I and others could enjoy. Who me an artist?

During 2020 we binged out on learning, not a bad distraction from COVID. We became active members of the recently established Lens School and I did two online programmes with Valda Bailey and Doug Chinnery. I made my first photography book, Close to Home - 20 images taken within 20 kilometres of our home in 2020, all landscapes using intentional camera movement. I upgraded my camera and bought a wide format printer.

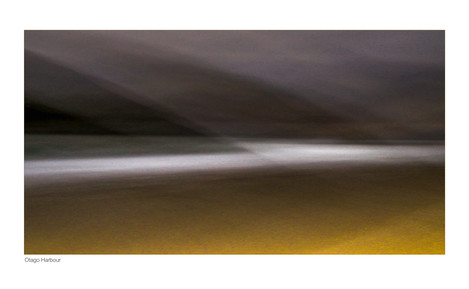

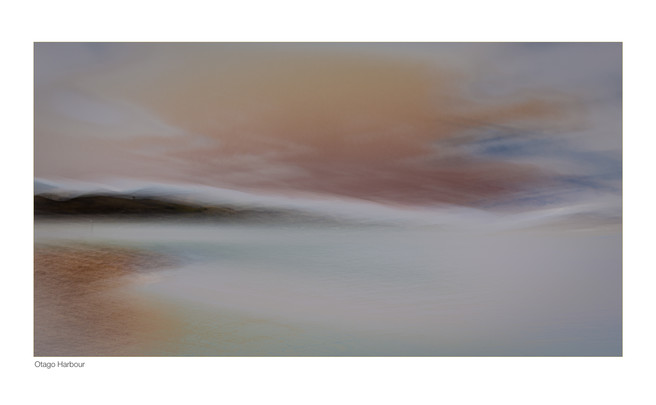

I have over the past year experimented with using long, generally 4 second, exposures during which I move the camera, and at times my body. My movements often mirror the contours of the landscape, be it a ridgeline, seashore, a valley or the margins between different components in the landscape. For me, this has become a process of engaging emotionally and intellectually with what is being photographed. It gives me a creative buzz and on occasions produces some satisfying results.

Rather than carefully composing and with the click of the shutter “capturing” the view in front of me, I want to engage with what I am seeing, move with it, play with an idea and immerse myself in the hugely satisfying process of creating a landscape. I also enjoy using multiple exposure techniques to create an image in camera. By the way I still do some “straight” photography.

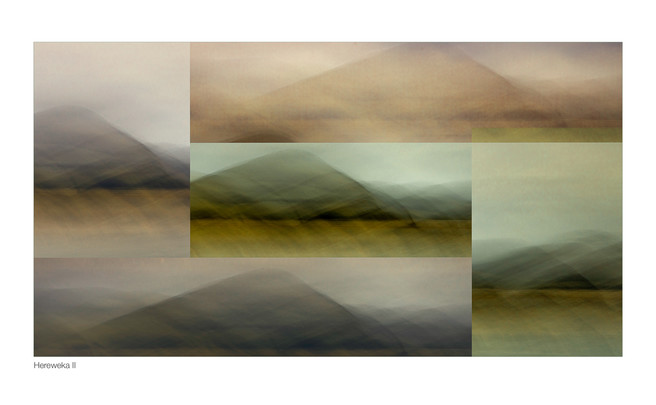

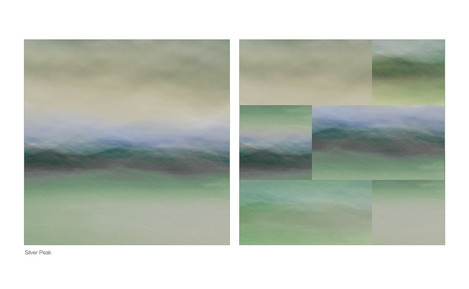

Mid 2020 as a family we were invited to Government House for an occasion and I was inspired seeing for the first time a painting - Fugue III - created by New Zealand artist Elizabeth Rees in which she “deconstructed” and “reassembled” the landscape. The idea of fugue in musical composition intrigued me, with Rees’ style providing a departure point for my more recent work.

I am currently transitioning from fulltime work and have been giving a lot of thought to the notion of purpose and what it is that gets me up in the morning. I am recognising that one of the things that gives me huge joy and satisfaction is the process of creating, be it writing, problem-solving, designing a workshop or a presentation, throwing a pot as a potter or more recently using a camera as an “artist” to create a work of art.

- In the Maori creation story, it was Tãne the god of the forest who separated Earth and Sky allowing light to shine on the earth so freeing the world from darkness. This whakatoki (proverb) is often used as a metaphor for the attainment of knowledge or enlightenment.