A dialogue with the landscape

Elliott Verdier

Elliott Verdier is a young French photographer who attracted attention and awards few times for his reports on human condition done in different parts of the world: Indonesia with afghan refugees, Burma with drug addicts in a rehab centre or Mongolia in polluted suburbs of Ulanbaataar. He has now decided to dedicate his photography to long term projects, far from hot news, entering into intimacy of the people he takes pictures of, with his 4x5 large format camera.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

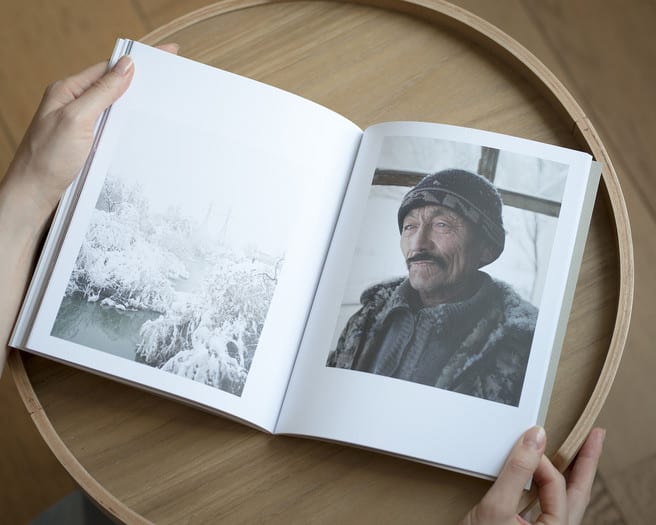

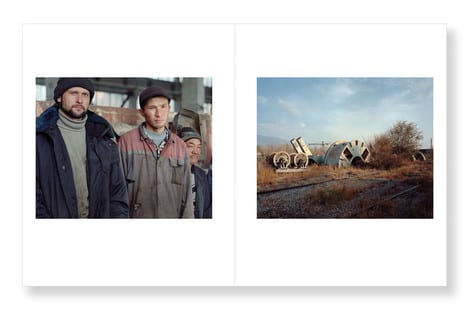

Back in September 2017, Elliott submitted his work for our 4x4 portfolio feature. The project was based on four months in Kyrgyzstan, highlighting the generational disparities between those nostalgic of the abolished USSR order and modern westernised youths born after the fall. All images were made on his 5x4 camera that he uses.

Since then Elliott has published a book with UK company, Another Place Press, and had an exhibition at the Andrée Chedid space of Issy-les-Moulineaux, Paris. We caught up with Elliott to find out more about the project and how he came to photograph in Kyrgyzstan.

Tell me about why you choose landscape photography? A little background on what your first passions were, what you studied and what job you ended up doing (if not photography)

I would describe myself as only a landscape photographer, I wanted to be a photojournalist from very young. My godfather was a print collector and I spent a lot of time with him looking at his collection. He shared with me his sensitivity and love for photography. I think that I originally liked the romantic vision I had of lonely photographers travelling around the world, having incredible culture and experiences, living a thousand lives.

When I was 19, I received a grant to undertake my first trip as a photographer - a series of portraits of former Karen soldiers who were victims of land-mines, in Burma. Since then, I’ve been to a photography school in Paris and travelled for several projects during the summer holidays. I went to Burma over and over again, documenting drug addicts and the Rohingya crisis, but also visited Mongolia and Indonesia. There I spent a month with three Afghan refugees, living with them in a slum area, getting to know them more deeply than anyone I photographed before. It changed my relationship with the people I photograph, and more widely, the way I wanted to document things.

Tell us about your passion for Kyrgyzstan and your connection with the region and its people.

I like to travel to places that a man like me, born in a middle class family from Paris, would have never been. Meet people I would have never met. I want to testify of the world apart from hot news, with deep social issues, to take time and break into people’s intimacy. This is why I try to find original themes that suit my everyday quest for beauty through struggling people full of nostalgia, melancholy and sensitivity.

I was more and more interested in Central Asia after my trip to Mongolia. And I remember looking at a map and wondering what was Kyrgyzstan. I literally had never heard of this country before. I know, it’s a shame! I started doing some research on it and found very little about it. So I decided to go for a month to see by myself at first. I think I will always remember the first time I arrived in Kyrgyzstan. It was dawn. The soft pink light of the rising sun was touching the wall of mountains in the south of Bishkek. It was all quiet. Everything there seemed eternal. I decided to go back for a longer time and a bigger project.

What came first the idea for the book or the photography project?

Definitely the photography project. After my first trip in Kyrgyzstan without taking any photos I liked, I definitely knew I had to make a change somehow. I worked a couple of month in a bar, bought an analogue camera I have tested once to an old man, three hundred films, and went again to Kyrgyzstan with no return ticket. Fortunately, I had a grant a month later to pursue the project, because I really don’t know how I would have lived there and developed all the films… The project drew itself by the time I have spent there.

How did the project evolve into an exhibition as well? Did that impact on the style and type of images you took?

I have spent 5 months in Kyrgyzstan doing some images and defining more and more the project day after day. I never knew that will end up with a book or an exhibition. But I knew this project will be different from the others, by the time I have spent doing it, but also by the way doing it, with my large format camera. The deeper I was documenting the country, the greater dimension I knew this project was taking.

What story did you want to tell with the reader? How did you go about structuring the images to develop this story? Did you have a creative idea of what the images would be?

I have once read a comment under an article presenting ‘A Shaded Path’ that was saying: "It’s not Kyrgyzstan who is depressing, it’s the photographer who is depressed". After laughing a bit, I realised how accurate this comment was, even if depressed is not the more appropriate definition for me. ‘A Shaded Path’ is about Kyrgyzstan, but it’s more about people, individuals, their interaction with landscape, and of course, as photography is undoubtedly subjective, it tells about my perception and the feelings that influence it.

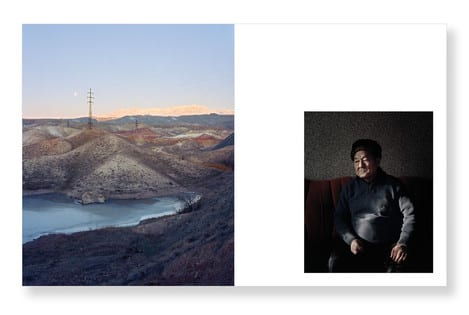

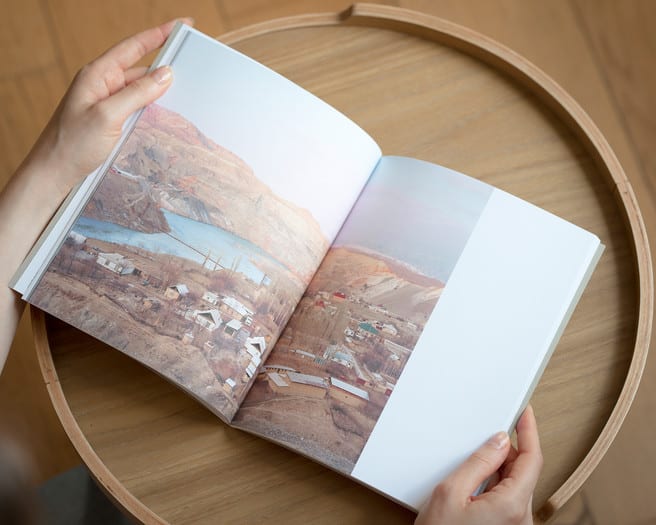

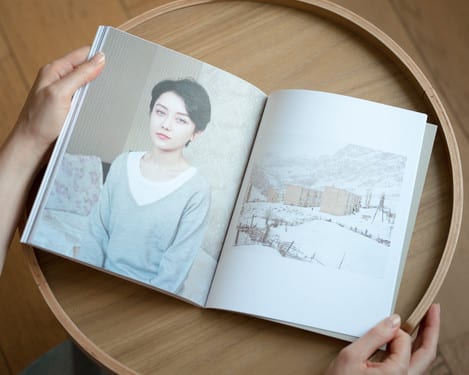

I think I always had a kind of melancholy in me, and Kyrgyzstan emphasised it, all ingredients there and in my life at this precise moment drew this portrait of a woebegone country, with persons stuck between past and future. I believe ‘A Shaded Path’ is many more things than depressing, I like to see it as a blend of subtle emotions. A human story after all. And I wanted them to dialogue with the landscapes. The dialogue that happens between the portraits and the landscapes can speak of many subjects but one stood at the forefront of my mind. Despite their contextual importance, these landscapes show how man can adapt his environment to his own wishes yet his surroundings always win out in the end. They show the passage of man, the wear they put upon their environment. In essence, they represent the fleetingness of man.

How did you go about researching, planning the photography trips for the book etc? i.e. Was it one trip or multiple trips? What challenges did you have along the way?

As I said before, it was only one trip of 5 months.

You mention in the introduction to the book 'the young republic of Kyrgyzstan is a contradictory Neverland where great aspirations cross paths with remnants of a Soviet era How did you go about capturing this tension in the images to convey that?

The landscapes of Kyrgyzstan bare the traces of its soviet history. I wanted to capture that, among other things, to set a fantasized forgotten country, cold and windy, quite unique. Some portraits are an open window to a more modern and globalized way of life. They mainly contain this tension, this struggle, this subtlety that contrasts with landscapes that don’t have this double lecture. I try to make people in portraits look like soaked by their environment, but dreamful about their future.

Which images gave you the hard challenge creatively?

The coal miner in Min Kush. He was walking to the mine with his picks in the snow of the mountain. I took him in the car. The mine was still so far away. When we finally arrived, it was -18°C. I really wanted to shoot him and his white working clothes in the black mine, as he was eaten by darkness and fighting it, but it was very difficult as I was on slippy sloping rocks. It took time, but this guy never moved or lost patience, he looked like he was truly glad and thankful he could testify of his way of living. He was posing for posterity.

Sequencing is obviously important - how did you manage the flow of the book with the images and the visual narrative?

Once again, I really wanted the landscapes and portraits to dialogue. One is answering to another. But a few times, portraits opposing completely different persons are also answering themselves, and look familiar, finally united under the same melancholy.

The only chronological aspect of the sequencing appears in the weather. I wanted to begin by an image obviously made in autumn, soft and calm, and go deeper and deeper in the winter, finishing by those cold and white landscapes. I wish it shows a certain feeling of time flowing, but also a loss of bearings, like the Neverland I wrote about earlier.

Did you manage the project yourself or did you work with an editor?

In my opinion, the finality of photography takes place by printing and publishing. These are things that exist long-term. In a time where images are consumed through screens, a wide range of mediums were made available, I think the younger generation of photographers are becoming more aware of the notion of the ephemeral image and therefore are trying to make their work live longer through more traditional ways of communicating their images.

Fortunately, Iain Sarjeant, from Another Place Press, came to me quite quickly to offer me the possibility to publish with him and his edition.

How did you decide on the format of the book e.g. size and paper, print type?

How did you decide on the format of the book e.g. size and paper, print type?

Another Place Press aims to produce a range of high-quality affordable books. All their collection does not come in large formats. It really suited me fine as I didn’t want something huge, but intimate. I chose an uncoated paper to accentuate the faded, vanishing sensation you would feel discovering this country on the outskirts of global headlines.

Where was the book printed and how was the experience of working with a printer?

The book was printed in the UK and I was unfortunately not able to be there.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography?

I chose to do this project with a large format camera, for two reasons: I wanted to have a special quality that it offers and take the time to do the images. Large format camera requires time to settle and for settings, I like to take this time for photography, and I especially did in Kyrgyzstan. It is quite long, heavy, inconvenient, and costly, but at the end, it’s definitely worth it. Last reason also, for portraits, I like people’s reaction in front of a large format camera. As a photographer, you get more credibility, but they are also posing differently. They are more serious. They naturally pose for posterity.

What sort of post processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

Back in Kyrgyzstan, I was sending my negatives to Paris threw people travelling over there. One of my friends was waiting for them in the city and was taking the films to the lab. The lab developed them, scanned them in low resolution, and sent them back to me digitalised. I could know what I was doing. When I came back I started selecting ones for the series and took them back for a higher resolution scan. Sometimes, the film has some weird colours or is over contrasted, I really can’t be 100% sure of what the result will be when I use my large format camera. I am not that experienced with it.

What other projects are you currently working on and can we expect another book?

I’m very happy to recently begin getting assignments thanks to A shaded Path for publications such as Vogue Italy or The New York Times. But of course, I would like to make another documentary, maybe even deeper, because long term projects are what truly drives me in photography. I am preparing something about collective resilience in Liberia, planning a first and short trip there in mid September. I’d like my work to follow some themes I value, something around time, memory, and existential struggle.

Copies of the book are available from Another Place press here and are £17.