David O'Brien chooses one of his favourite images

David O'Brien

David recently retired from his role in the legal profession and is looking forward to spending more time on his photography (as well as with his family!).

Although he has an ongoing flirtation with digital photography, his real passion is film photography, particularly medium format and film pinhole cameras. Instagram

And now for something entirely different. There are plenty of end frame articles (and for good reason) where the chosen image has been like a cherished friend, something well known for many years and returned to, often. I have many such favourites that would instantly spring to mind. But my choice for end frame may well buck that trend and is a more recent “find” from the expansive photography repertoire of Sir Wilfred Thesiger (b.1910 – d.2003), perhaps one of the last century’s greatest travel explorers - and one who may be known more for that fact than his photography.

A scant awareness of Thesiger’s middle eastern travels sufficiently piqued my curiosity to attend a curator tour at the Said Business School in Oxford for a recent exhibition, “Contrasting Arabia – Hotel Zaatari & Wilfred Thesiger” where a dozen or so of Thesiger’s images were on display (including the chosen image for this end frame submission). With Thesiger’s well-known admiration for the peoples he lived with and photographed, the exhibition - mostly portraits but some landscapes too - was seeking to make a contrast between the peoples and cultures Thesiger encountered with the harsh everyday life of Syrian refugees (as captured by modern day photographers). My personal preference was for Thesiger’s imagery which struck me as natural and unburdened by the resonance of current day experiences.

Everybody likes an adventurer and I guess most would like to travel more than they currently do. With more time on my hands, perhaps this is what caused a re-awakening of my interest in Thesiger, a desire for a sense of adventure with my camera. Thesiger’s work certainly does resonate strongly - a sense of wanting to see and experience the places he has captured with his camera.

Before turning to the chosen image of this article, a brief introduction to Thesiger might be merited. It would be an injustice to call Thesiger an old-school T.E. Lawrence type with a camera but his extensive travels throughout Africa, Arabia and Asia in the 30’s through to the 60’s, prior to the more recent transformational changes of revolution and conflict in some of those regions, have been brought to life by Thesiger’s 35mm Leica film camera. While Ansel Adams was laying down the foundations of black and white photography in the wilds of the great national parks in America, Thesiger was rampaging around the deserts of the Middle East, particularly the Empty Quarter, an environment so hostile to life that few had traversed it. Anybody who attended the coronation (by invite) of Haile Selassie was destined to have a colourful life it seems, and Thesiger certainly lived up to the expectation. Upon his death in 2003, an inheritance tax settlement with HMRC allocated some 38,000 black and white negatives to the custody of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford –an important photographic archive saved for posterity.

Thesiger, a largely self-taught photographer, realised that he could bring to life the incredible scenery he witnessed and the peoples whose cultures he respected and cherished. With the need to travel light (sounds familiar?!), Thesiger kept it simple – Leica film camera, fixed length lens, black and white film, yellow contrast filter and the occasional use of a polarising filter, all carried in a goat-skin bag. Images were handheld without the use of neutral density graduated filters. On occasion, films were left unprocessed for over a year. Unburdened by the many considerations of the modern-day photographer, and having a trust in and familiarity with, a camera set-up that a lifetime experience had brought, Thesiger could focus on the subject composition and the capturing of light/shade to enhance that composition. And what astonishing and varied images he produced. Over time, Thesiger had become a highly-skilled photographic artist.

The geographical remoteness he consciously sought out has ensured that Thesiger’s impressive photographical archive is a treasure trove of portraits and landscapes that are almost unrecognisable in the modern era. It was a breath of fresh air to see something entirely new - whether subject matter composition or photographical style. I marvelled at the chosen image of this article when I saw it for the first time and continue to marvel at it now as a quickly-ordered print now hangs on my study wall as I write this article. Thesiger’s strongest suit is undoubtedly his portraits and his “greatest hits” collection - containing both his portrait and landscape work – are brought together in a single volume, Visions of a Nomad (Collins, 1987). I would certainly recommend this book for those who are further interested.

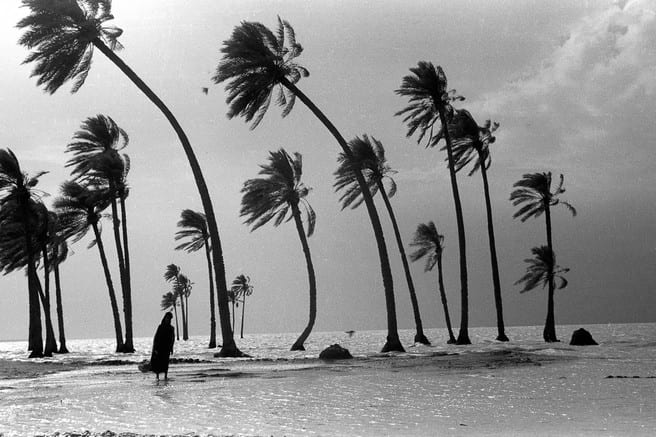

Between 1951-57, Thesiger found himself in Southern Iraq. A short trip intended for a fortnight’s duck hunting found him eventually staying in the marshes of Southern Iraq for nearly 7 years. At this stage, no European had lived amongst the Marsh Arabs (or Madan), an indigenous people who lived in reed houses built on small man-made islands. Trees in Gale is an image produced during Thesiger’s stay here - taken near Hamar in 1953, a year reputedly of great floods in the region with floodwaters six feet deep and covering the desert on the western edge of the Marshes.

The simple graphic detail of the image is immediately eye-catching; I was drawn to the composition as soon as I glimpsed it out of the corner of my eye - if I were present, I would certainly have been drawn to make an image. But there were no tripod holes where Thesiger travelled and many of these regions have been much changed by the cultural and political revolutions of the last 60 years. The image solicited an immediate response from the viewer - I wanted to be there, looking through Thesiger’s viewfinder, seeing what he was seeing - the light of a passing storm is often unique and I doubt that Thesiger confined himself to a single frame capture at this location.

It’s not immediately apparent but the foreground female figure, seemingly struggling against the wind, is actually walking towards the camera. The recently-purchased print more clearly shows this; my initial inkling (all subconscious) was that the figure was walking away (from the camera), leaning into the wind. Good separation between the trees (certainly a deliberate compositional choice) enhances the composition; the addition of the lone female figure gives a human interest (on which we know Thesiger was so keen) and a sense of scale. It’s a simple image but in a world of saturated imagery (for which I also plead my guilt!), this has a dynamic freshness and has whetted my appetite to stray beyond typical holiday destinations and visit more exotic climes.

The palm trees straining in the wind, with a frond just detaching at the point of image capture, belie the strength of the gale force wind. Thesiger, in his books, recounts how he does wait for the right moment to take an image (these are not simple record shots), so we are encouraged to know that the timing of capture is deliberate and intentioned. The deeps greys on the horizon and the highlights on the water perhaps show the storm has just passed and the strong sunlight (nicely silhouetting the trees as we look at the image) introduces deep and pleasing contrasts into the image – it’s all about the angularity of the now water-submerged trees as they struggle to remain upright in the gale. The lack of sky detail (it didn’t concern the likes of Dombrovskis!) equally doesn’t bother me; a stormy sky isn’t what this image is solely about but the hint of the stormy dark horizon hues provides a pleasing context to the composition.

One will also notice that the horizon isn’t straight. Given this is repeated in the book publication, the high res digital scan produced here (without amendment from the scan provided by the Museum) and in my image print copy, I tend to think this reflects the original negative image (rather than a poorly-aligned scan). My perhaps romantic conclusion is that the photographer wished to show the strength of the gale with the world almost leaning over in sympathy! Others may be less forgiving.

Beyond the draw of the strong visual aesthetic of this image, it resonates in other ways as I imprint my own feelings and experiences - I think of climate change, the plight of peoples and threatened cultures, the effect of globalisation on communities and the environment (a concern which Thesiger himself voiced on his travels). Above all, I wonder what this scene looks like now…are the trees still there? Are the Madan still making their reed houses and boats? I might need to get down to that travel agent after all and pack my bags!

We are looking for end frame articles for our forthcoming issues. So please do get in touch if there's an image that you want to write an article about.

Notes

- Trees in Gale has been reproduced under a publication license granted by the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and is © Pitt Rivers University of Oxford (2004.130.3751.1).

- More details on this image and in which of Thesiger’s books it has been published can be found at - http://photographs.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/2004_130_3751_1.html

- The Pitt Rivers has a dedicated website section for Thesiger and his imagery which can be found here - http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/thesiger/index.html

- The current exhibition - “Contrasting Arabia – Hotel Zaatari & Wilfred Thesiger” - is a curator tour only exhibition which is being held weekly until the beginning of December. Tickets are free and can be obtained through Eventbrite.