Featured Photographer

Sarah Marino

Sarah Marino is a nature photographer, photography educator, and writer who splits her time between a home base in rural southwestern Colorado and living a nomadic life in an Airstream trailer. In addition to photographing grand landscapes, Sarah is best known for her photographs of a diverse range of smaller subjects including intimate landscapes, abstract renditions of natural subjects, and creative portraits of plants and trees.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

For this issue, we’re slowing down and wandering around with Sarah Marino, a photographer, educator and writer who together with husband Ron Coscorrosa splits her year between home and a nomadic life in a trailer. From the latter, you might expect a portfolio full of iconic American scenery, but over time Sarah has found greater fulfilment through the changing conditions, intimate scenes and delicate details for which she is best known.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself – where you grew up, your education and early interests, and what that led you to do as a career?

I grew up in a suburb of Denver, Colorado in the United States. Although I did well in school and had a lot of ambition, I didn’t have a strong sense of what I wanted to do with my life and made some poor decisions as a young adult. I was the first person in my family to go to college and initially enrolled at a prestigious engineering school. I succeeded on the academic side but the cutthroat culture of the school was not a good fit. I transferred to another university and graduated with two degrees – one in American history and one in business. I was involved in political advocacy at the time and found my first professional job on a congressional campaign, with the plan of going to law school soon thereafter.

After an intense and mostly unpleasant experience on the campaign, I again realised that highly competitive environments are not a good fit for me and I decided against law school. Feeling rudderless, I applied for a wide range of positions and ended up accepting a job offer at a large nonprofit organisation. Finally, and mostly by accident, I found a culture that was welcoming, collaborative, and mission-oriented – a much better fit. This job led me to a happy, wide-ranging career in Colorado’s nonprofit community, including owning a nonprofit and philanthropy consulting business for almost a decade. While I still work with a few long-term consulting clients, I am getting closer to working as a full-time photographer each year.

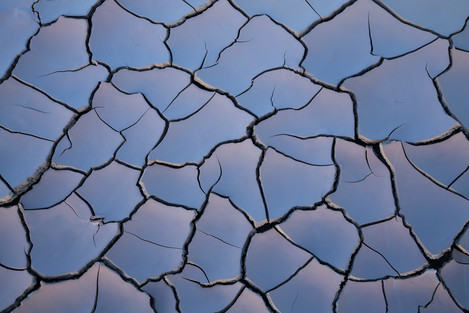

A recent rain smoothed out and softened the surface of formerly weathered mud tiles in Death Valley National Park, California.

How did you become interested in photography and what kind of images did you initially set out to make?

About five years into my nonprofit career, I decided that I needed a graduate degree since I wanted to become a CEO and lead a large organisation. I finished a master’s degree in public administration while working full-time in an intense, high pressure job.

As I started taking my photography more seriously, I also started experiencing the thrill that can come with external validation. At the time, Marc Adamus was emerging as a driving force in the US landscape photography community. I decided that I wanted to take photos like Marc’s photos, mostly because those types of photos received the most attention. I completed three workshops with Marc and they were instrumental in my development as a photographer. During the first workshop, observing Marc’s adventurous spirit motivated me to build my outdoor abilities and skills (and I learned a lot from observing his creative process). During the final workshop about a year later, I realised that copying Marc’s photos and style offered little in terms of personal satisfaction and I started the slow journey back to focusing on the types of subjects that were among my initial inspirations.

Who (photographers, artists or individuals) or what has most inspired you, or driven you forward in your own development as a photographer?

My interest in nature is the driving force and inspiration that has propelled me forward as a photographer. As I spend more time outside, I find more things that fascinate me. The feelings of discovery, wonder, and awe inspire me to get outside more often, explore the same places more deeply, and experience new places.

While I admire many nature photographers, I actively try to keep the work of others from directly inspiring or heavily influencing my own work. When it comes to photography, I have an impressionable mind, especially with regard to visiting specific places. This led me to partially adopt a practice that photographer Cole Thompson calls photographic celibacy.

As I analysed how I was working, I came to the conclusion that when I studied another photographer’s work, I was imprinting their style onto my conscious and subconscious mind. And then when I photographed a scene, I found myself imitating their style rather than seeing it through my own vision. To overcome this tendency I decided to stop looking at the work of other photographers, as much as was practically possible.~ Cole Thompson

For about a year and a half, I spent very little time looking at nature photography, with the exception of occasionally seeing the photos shared by friends on social media.

Almost every time I discuss these ideas with other photographers, I get strong disagreement so I know that this practice doesn’t work or isn’t compelling to most people. However, when I consider my biggest breakthroughs and periods of progress with my own photography, this approach was essential.

How have your experiences over the last 10 years changed your perspective on life and the necessity of making a living?

My only sibling passed away after a bicycle accident when I was 14 years old and it was an incredibly traumatising and consequential experience. I can trace most of my ambition and the constant feeling that I need to fit in as much as possible to this experience. This initially manifested as a drive to be a top achiever in school and then morphed into a desire to accelerate professional accomplishments. While this approach produced an impressive resume, it also left me feeling emotionally tattered and constantly stressed. I daydreamed about taking a year off to rest and focus on photography but given my situation at the time and my addiction to work, making it happen seemed impossible.

In 2011, I met my now-husband, Ron Coscorrosa, during a photography trip in southwestern Colorado. Ron had saved up so he could take a sabbatical from his work as a software engineer. While I initially had no romantic interest in Ron, I found his life choices to be instantly inspiring because, at home, I was surrounded by people who only defined success through career-oriented achievements. Getting to know someone who defined success in terms of enjoying life was a revelation and it motivated me to start making different choices. At the time, I had a busy consulting practice and selected projects based on things like prestige and visibility. I started instead of selecting projects that allowed me to work remotely and maintain a flexible schedule. I also went through a long, difficult process of crafting a new identity – one that wasn’t based solely on traditional career success but instead of actually enjoying life.

Once we got married, we significantly reduced our expenses, moved to a small town with a lower cost of living, and figured out a way to travel a lot more (finding remote work, buying an RV, and introducing our cats – successfully! - to travelling). While I make a lot less now and still feel self-induced pressure to cram in as much as possible, I am much happier living a simpler, slower life with more time for travel, being outdoors, and photography.

Across the breadth of your portfolio, which places, projects or themes have the most resonance for you?

This is a hard question to answer because every natural place I have visited resonated with me in some way. Still, I feel most at home in wide-open desert landscapes. Exploring is easy since cross-country travel is allowed in many places. Desert landscapes also seem to hold more surreal surprises than other types of ecosystems. It is exhilarating to head out to a familiar place and not know what we might find since some desert landscapes can change dramatically after flooding or extended periods of dry weather. As noted in 1-star Trip Advisor reviews for places like Death Valley National Park, these landscapes can look like desolate expanses of brown at first glance. With a closer look, however, such places are often full of life and are transformed under different lighting throughout the day. All these things come together to make such landscapes feel magical.

I also spend a lot of time seeking order among chaos. This is probably the most common theme in my photography, as I find the greatest pleasure in finding patterns and repetition in nature. It is fascinating to see patterns repeat in all different kinds of subjects and at all different scales. Finding these subjects, being able to photograph them, and then presenting them in cohesive collections bring me a lot of joy.

Would you like to choose 2-3 of your favourite photographs and tell us a little about why they are special to you?

Edge of Light

The edge of a sand dune catches the last light of the day at a remote dune field (Death Valley National Park, California).

When comparing my black and white work to my colour work, I think my black and white work is a better representation of my interests in and affection for the natural world. I always feel constrained when working with colour photographs and my perfectionist tendencies often get the best of me. For example, I took this photo in the late afternoon. The shaded sand dunes took on an unattractive shade of brown. By portraying this scene in black and white, I could get past my issues with the brown dunes and accentuate the strong contrasts in a way that would look artificial if rendered in colour. This photo remains one of my favourites because of the frill of wind-blown sand – a little detail that makes the photo for me.

Seaweed Patterns

I took this photo across the street from one of Iceland’s busiest photography spots. This is an interesting place to observe photographers because most people get out of their car, walk the short distance to get “the shot,” get back in their car and drive away. It is sad to see how few people explore since the area offers many subjects for photography – tidal flats full of this seaweed, extensive sand ripples, areas of standing water that reflect the surrounding mountains, and a series of pretty cascades all within five minutes of walking from the parking lot. When people ask me about my photography style, I say that I photograph by wandering around and my photos are the result of what I find while on these meanders. This is an example of how easy it is to find subjects just by wandering around. I continue to enjoy this photo because of the repetition of the beautiful, intricate patterns in this seaweed. The slight wetness also adds a bit of a silvery sheen, which I love.

Many photographers work in a solitary manner – at least while in the field. Can I ask you about the dynamic of working jointly with your partner Ron? How much do your vision and style have in common, and how do they differ?

Ron and I are fortunate to have remarkably similar interests when it comes to being in nature, like our mutual affection for desolate landscapes and spending a lot of time seeking out tiny subjects. Since our interests align, we are able to easily choose places to visit that interest us both. If we are visiting a place that requires hiking to access the spot we are planning to photograph, we almost always hike together and then split up once we arrive at our destination. If we are photographing from the car or a parking lot, we sometimes spend a little time exploring together but much more commonly go off in our own direction.

One of the most common questions we are asked is, “Who is the better photographer?” This question is confounding since we never think in these terms, as we are not territorial or competitive at all. If I see something interesting, I am often as excited about sharing it with Ron as I am about photographing it myself.

Ron is a carefree person and just enjoys being outside. He never puts pressure on himself and rarely brings expectations to a place. I, on the other hand, sometimes feel the pressure of a moment. This last winter, we made a detour to Zion National Park because of a forecasted snowstorm. I have wanted to photograph this area with a coat of snow for many years and this happened to be the first time that everything aligned for us. The snow was magnificently beautiful but was already melting by the time we were up for sunrise.

Instead of enjoying the experience, I ended up feeling a lot of pressure and stress because of the uniqueness and fleeting nature of the conditions. Ron, with his more low-key approach, enjoyed it a lot more and is happier with his resulting photographs. This dynamic is why I am most happy showing up at a place without a lot of expectations or a plan I enjoy photography a lot more when I can move at a slow pace and just see what a place has to offer without the pressure of rare conditions or a lot invested in a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Comparatively, Ron can excel in both situations. The more time I spend with him, the better I am getting at adapting my inclinations to his style and it has improved both my photography and experience as a result.

Which bits of gear have survived you ;-) and can most often be found in your camera bag?

A few years ago, I had a rough phase with gear: dropping a lens onto a sidewalk, watching a lens slowly roll out of my bag and down a 30-foot hill before plopping into a cascade, and ruining a camera in heavy waterfall spray. Since then, I have tried to be more careful with my equipment although I do still joke that it is not the smartest move to buy used gear from any nature photographer…

I use Canon equipment including the Canon R mirrorless camera, plus 16-35mm, 24-105mm, 100 mm macro, 70-200mm, and 100-400mm lenses. With the exception of the 70-200mm lens, which I reserve for longer hikes since it is lightweight, I always carry the other four lenses in my camera bag and use them in similar proportions.

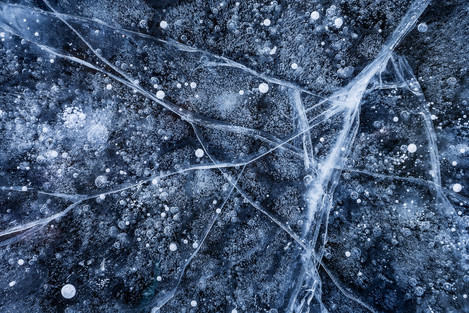

Death Valley National Park’s flooded salt flats, which looked like ice on this cold morning in the desert.

Can you give readers an insight into your workflow from the point of image capture to output?

In the great debate about Photoshopping and “fakery,” I fall somewhere in the middle of the continuum. I want to present my subject at its best and will accordingly fine tune things during processing but also want to stay grounded in reality. For me, the power of nature photography is rooted in the idea that the photographer actually experienced the moment they are presenting. While dropping in a better sky or perking up a mountain might be a fully valid creative choice, learning that the photographer didn’t actually experience the moment of awe as they are presenting it takes away something valuable for me as the viewer. Thus, I want to maintain what I see as authenticity when presenting my work, especially with my colour photography.

Conversely, one of the things I enjoy most about black and white photography is that the starting point itself is a departure from reality. This provides significant creative freedom – a freedom that I more fully realise when processing my black and white photographs. This typically means building significant contrast into the scene, with strong light and dark tones, using levels, curves, and basic luminosity masks as my primary tools in Photoshop. My process also includes emphasising or deemphasising specific elements of a scene through dodging and burning. I use many of the same tools for my colour photography, just with a much lighter hand. I generally want my black and white photos to be visually striking and more aggressive whereas I want my colour photos to convey grace and elegance.

Workshops, done well, are an important source of income for many professionals but is there a danger that their proliferation encourages learners to think that everything they need to know or do can be achieved via this route? We learn a lot from experimenting and failing and following curiosity and resisting the pressure to get it right and show the evidence of this. Where might a balance lie?

The opportunity to learn from an experienced professional in the field can be invaluable and even transformational.

As an illustration, we were photographing coastal scenes one evening in Olympic National Park. We came upon a workshop taught by a well-known photographer. He planted his ten students in one spot, all facing the same direction and photographing the same subject in the same way. There were no clouds behind “the shot” but there were interesting clouds in other directions, plus a lot of other potential scenes and subjects up and down the beach. In watching this scene unfold, I was frustrated for his students that they were being taught such a narrowly focused approach to nature photography. In other settings, I have seen a similar approach to teaching, with workshop leaders talking about how a location always has one composition that is the best or telling students to focus on what they came for (the grand landscape) rather than what catches a student’s eye (some shiny mud patterns).

A good number of students want to be brought to the best locations and instructed on the best compositions. I fully understand that this approach meets the needs of a lot of instructors and their students. However, I think the field of nature photography and individual photographers would be better served if more workshop leaders took less of a checklist approach and offered more education on personal expression, how exploration can create unexpected opportunities, how to see beyond the obvious, how to cultivate curiosity, and how to adapt to changing conditions. The latter helps instil a set of skills that is perpetually useful and can help set a photography student on a more personally fulfilling path in the longer-term.

How would you advise readers who feel that you must have a plan – about where to go and what to photograph?

I always think about a particular story when discussing this topic because it is such a dramatic example of how expectations can eliminate opportunities and stifle creativity. A student came to a friend’s workshop with the goal of photographing waterfalls. The conditions were not conducive to photographing waterfalls but were excellent for forest scenes showcasing fall colours. The student ended up leaving the workshop early because she couldn’t see past her expectations while the rest of the participants enjoyed one of the best autumn seasons in memory. The simple lesson: minimise expectations, keep your plans flexible, and you will likely be happier as a result.

While this advice is simplistic, I think it is a key to finding more satisfaction in nature photography (excluding certain types of photography which require a lot of planning, like night photography). I offer this advice because following it has been transformative for me since I used to be heavily driven by expectations and pre-conceived ideas. Now, I try my best to minimise my expectations for a place, free my mind of specific photos I might want to take and open myself up to what I see one I arrive. I slow down and wander around, photographing the things that catch my eye along the way. I do not always succeed (see: Zion example above) but generally, have found this approach to be much more fulfilling than the alternative.

Many of the people that we’ve interviewed have come to photography through a love of the outdoors and outdoor pursuits but I guess it may now only be a matter of time before someone does admit that they got into photography through what they saw on social media. Visual outputs have always influenced us but they weren’t previously so obviously linked to statistics (popularity and ‘success’, whatever that means). How can we moderate the risk that nature once again becomes something to exploit for our own end? Is photography still a force for good, or are we now becoming part of the problem?

At least in the United States, nature photography has historically been a major force for good. Many conservation campaigns have been propelled forward and achieved success because nature photographers have helped create a compelling visual record of what could be lost without preservation. For previous generations, even photographers without a personal conservation mission often came to photography first through their love of and experience in wild places. This meant that a photographer would learn about Leave No Trace and other wilderness ethics along the way.

Now, many people are coming to nature photography through social media, especially Instagram, which has created the dynamic in which nature is seen as an expendable commodity. The recent poppy bloom in southern California is an illustrative example of how social media encouraged a lot of people without grounding in outdoor ethics to visit a place, treat it with disrespect (sometimes unknowingly and sometimes intentionally), and cause irreparable damage in the process. While it might not seem like a big deal for one person to step off a trail, the cumulative effect of hundreds of people doing so can be significant.

Bright maple leaves and a few green oak leaves stand out among a less vibrant bed of fallen leaves in Zion National Park, Utah.

Increasingly, individual photographers can reach thousands of people with a single post. With reach comes responsibility and the need to acknowledge one’s ability to impact behaviour for the good or bad through our photographs and messaging. Beyond individual photographers, news organizations, commercial brands, and tourism agencies bear a lot of responsibility for these trends, as well. For example, one major camera brand posted many photos of people frolicking in wildflower fields during the same super bloom, often with hashtags inviting people to share their own similar photos. This sends the message that such photos get attention and thus should be imitated if you want to be featured by that brand in the future.

To start addressing this swirl of complex issues and negative impacts, a group of Colorado-based nature photographers came together to create the Nature First movement, starting with 7 Principles that nature photographers can follow to help minimise our collective impact. The 7 Principles include:

- Prioritise the well-being of nature over photography

- Educate yourself about the places you photograph

- Reflect on the possible impact of your actions

- Use discretion if sharing locations

- Know and follow rules and regulations

- Always follow Leave No Trace principles and strive to leave places better than you found them

- Actively promote and educate others about these principles

After launching on Earth Day in late April, more than 1,200 photographers from 40 countries have joined the Nature First movement. If your readers would like to learn more about the initiative and join for free, they can visit www.naturefirstphotography.org. Since we spoke about workshop leaders above, I also want to mention that the Nature First organising group offers some specific advice for workshop leaders and those with large audiences since we believe that such individuals have a special responsibility in modelling and educating others about these practices.

Steam from a nearby geothermal feature helps simplify this scene and show off the structure of this tree which has died due to its proximity to an encroaching hot spring. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming.

Do you have any particular projects or ambitions for the future or themes that you would like to explore further? A while ago you mentioned that you would like to move from eBooks to producing a printed book.

One of the best things about working as a photographer today is being able to reach an audience without going through traditional gatekeepers. We started self-publishing eBooks in 2013 and eventually added video tutorials. The ability to develop and sell these products has been a key part of being able to transition from my consulting career to making a living through photography. We plan to continue expanding our offerings in the future; this summer, we will be working on three digital portfolios and possibly new video tutorials.

One of my goals is to publish a printed book – either educational or a portfolio book - but it feels like a daunting endeavour at this point. I have started researching and writing a book on composition and have considered approaching some publishers to gauge their interest. Still, I keep on feeling the pullback to self-publishing since I would have more control over the final product and it would likely be more financially viable. Even if the composition book doesn’t turn into a printed book, I still hope to publish something other than digital products in the future.

Is it important to you that other people see your work in print, and if so, how do you choose to print and present your pictures?

Printing has been my single greatest source of frustration with photography and remains the area in which I have the most to learn. I love photography because I find great joy in being outside.

Without regularly sharing prints of my work, I know that I am missing out on a critical part of the photography process. We recently purchased a large format printer and one of my primary goals for this year is to significantly increase my knowledge of fine art printing and get to the point where I can confidently print any of my photographs.

If you had to take a break from all things photographic for a week, what would you end up doing? What other hobbies or interests do you have?

My main interests beyond photography include cooking and hiking, often while socializing with friends and family. I have slowly perfected my ability to bake a loaf of artisan bread, can now make an almost perfect pistachio gelato and have significantly expanded my ability to cook a good vegetarian meal from a broad range of worldwide cuisines. A few years ago, we moved from urban Denver to a town of about 1,000 people in southwestern Colorado so we spend a lot of time exploring this area. We have been choosing a region each summer and then hiking as many trails as we can, often without camera gear.

And finally, is there someone whose photography you enjoy – perhaps someone that we may not have come across - and whose work you think we should feature in a future issue? They can be amateur or professional.

Michele Sons. While I really enjoy Michele’s more traditional nature photography, as she has a talent for creating photographs that capture the elegance and grace of the places she visits, I find her Feminine Landscape series to be especially well done.

Thank you, Sarah. It’s been great to catch up with you.

If you’d like to see more of Sarah’s images, you’ll find her portfolio at https://www.naturephotoguides.com; she’s also on Instagram. You can read the blog post that Sarah wrote about minimising the impact of your photography here.

- An up-close look at a Joshua tree in Joshua Tree National Park, California.

- Glistening seaweed in a tidal flat in Iceland

- The edge of a sand dune catches the last light of the day at a remote dune field (Death Valley National Park, California).

- Steam from a nearby geothermal feature helps simplify this scene and show off the structure of this tree which has died due to its proximity to an encroaching hot spring. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming.

- A small waterfall flowing through moss-covered rocks in Iceland.

- A high-up view of the amphitheater surrounding a waterfall in Oregon’s Columbia River Gorge. The area surrounding this waterfall was heavily damaged in 2017 due to a massive wildfire started by careless people playing with fireworks.

- A recent rain smoothed out and softened the surface of formerly weathered mud tiles in Death Valley National Park, California.

- Colourful rocks below textured ice in winter in Zion National Park, Utah.

- A tiny section of pretty moss growing on a downed tree in Olympic National Park, Washington.

- A misty morning in Mount Rainier National Park.

- Layers of colourful mountains emerge from a clearing storm in Iceland’s rugged and remote interior.

- Lightning strikes the mountains behind the Great Sand Dunes in Colorado.

- A frilly desert plant at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Florida.

- Ice formations on a backcountry lake in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains.

- Bright maple leaves and a few green oak leaves stand out among a less vibrant bed of fallen leaves in Zion National Park, Utah.

- Fuzzy grasses capture fallen autumn cottonwood leaves in Zion National Park, Utah.

- Extensive badlands in the early morning in Death Valley National Park, California.

- Death Valley National Park’s flooded salt flats, which looked like ice on this cold morning in the desert.

- Dappled light travels across a dense tropical forest on the Hawaiian island of Kauai.