An interview with Charlie Waite

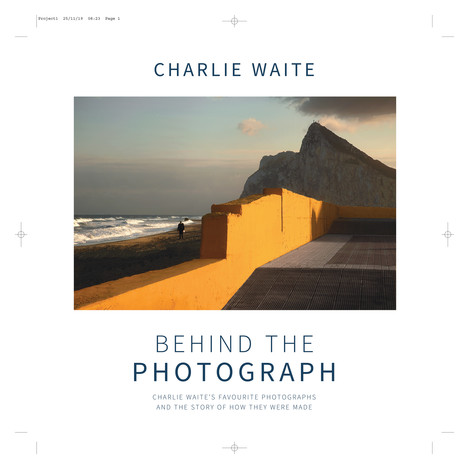

Charlie Waite

Charlie Waite is firmly established as one of the world’s leading Landscape photographers. His photographic style is often considered to be unique, in that his photographs convey an almost spiritual quality of serenity and calm.

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

With the launch of his latest book 'Behind the Photograph', it seemed like an appropriate time to catch up with Charlie and to hear more about how his background as an assistant stage manager affected how he sees light in a landscape and how his choice of cameras influenced his photography. Enjoy the read, as much as we enjoyed chatting with Charlie.

Tim Parkin (TP): I wanted to talk to you today specifically about your use of composition. It’s one of the things that most people seem to comment on as you have a unique look.

There’s a dominant school of photographic composition that is very David Muench - foreground/background, powerfully forced compositions - but your pictures are almost the antithesis. They are very much in a more painterly frame of reference if anything.

Before you picked up a camera, what was your visual education and what was it? Were you interested in painting? What was your exposure and influences before you thought about photography?

Charlie Waite (CW): The way you’ve phrased that question is quite unusual. I think I suspect it was born in my observing of the lighting directors in the theatre. I think that’s probably true as I always think lighting directors never really get the credit they should get. As they bring a play to life, they inject gravitas and pathos into it. Their name is often not on the programme, it might be but very very small.

Actually in the way that landscape photographers or photographers generally until the late 1970s maybe, who were illustrating books, sometimes they didn’t get a credit! Even if all the images were made by that one person.

I’m going off the point! But anyhow, that’s probably what it was and I noticed the way that wardrobe mistresses, set designers, actors, the director, all of them, they all got a lot of credit, but the lighting guy or woman didn’t. I was an assistant stage manager in theatre for quite a long time and I use to think “that’s clever”; he/she can just manipulate the audience or encourage the audience to look in a particular place or enjoy a particular part of the set. Especially shadows - I remember thinking how clever it is to create a shadow as opposed to a highlight and I’ve always thought that shadows play an absolute immense role even in a sitting room, and obviously lighting does.

When I say sitting room you don’t tend to have the same lighting as a dentist room! I wish they could change that! Wouldn’t that be better, if lighting was really pleasing and complemented the furniture, and was all together a much more enjoyable experience and to be part of. And yet they slam these neon tubes in - and banks are just as bad. If doctors waiting rooms could be more pleasing in terms of lighting, it would be great.

To answer your question though, instead of going off the point somewhat, I think in fairness, that would be my first influence. Watching how lighting and how stage lighting influenced the performance.

TP: You were, as I understand from your background, taking portraits of actors and maybe photographs of performances, would that be right?

CW: Yes, not many performances but actors you’re quite right. When I left the profession, jumping from the frying pan into the fire, going from acting into photography, I photographed many actors. I think the thing I really knew about that was that it’s a very invasive experience. People say, I don’t take a good photograph or I don’t like being photographed, everyone finds it difficult and people almost feel the victim when the camera is raised up at you. So I feel the business of being photographed was almost an ordeal for actors and everyone thinks that actors must have huge egos. On the contrary, they absolutely don’t, they are mostly quite timid and insecure. So I found that when photographing actors, the best thing of all was to encourage them to present themselves in their best possible mode and attack the camera. To have authority, a bit like a tennis match, and so that worked. I photographed thousands of actors over ten or fifteen years.

TP: Did you take inspiration for your photography from anybody? And talking about adversarial, it makes me thing the use of Yousuf Karsh

CW: That’s extraordinary! I was just going to mention him. It all stemmed from the pleasure I got from lighting from the theatre, and I learnt a little bit about lighting people. Oddly enough I looked at some pictures my dad took of my sisters in Germany and also a lovely photograph of him that was done in France when he was in uniform. I thought how clever it was that the side lighting and the jaw and the top lighting for people with thinning hair was skilful. I enjoyed that process. I like the acting fraternity, they are good souls. They are usually not what people think they are, they aren’t full of ego, far from it and not always that confident either.

TP: Who else would have been an influence at the time? Bill Brandt at the time maybe?

CW: Yes, definitely, although some of his images were quite spooky sometimes and quite punchy, contrasty, but I have a big admiration for him. I think you hit the nail on the head, he was as good as any. There’s also Irving Penn and a few others. Generally speaking I think it all goes back to the way the human body and face can be lit on a stage and to be presented to an audience. Complementary lighting was also important as every actor wants to look good. Seeing images, I think would be fair to say, that match the image they have of themselves.

I had a lovely interview ages ago by the assistant of a photographer who I can’t remember his name. The assistant was asked what was it that your boss, the photographer, always used to say to get the best out of people to get potency and a real authority from the person sitting for them. I’ll never forget him, he always used to say “If I’ve had it, I’ve had it a thousand times, I want you to look through the front of the camera, through the front of the lens, through the camera itself and out the other side of the camera. Through my eye, through my head, through the back of my head and a thousand miles further on.” It was a great line, I think what he was suggesting that they refocus on infinity, so they don’t focus on the object in front of the lens. That’s what gave the great Bette Davis “the look”.

I thought that was so, so good, so I didn’t exactly say that but I did sometimes say “have a high opinion of yourself. Treat it like a tennis match, serve an ace”. I can’t even get the ball back these days!

TP: When you moved on to doing landscape photography, how did you approach that in terms of composition and did anything transfer from what you’d done before in terms of portrait?

CW: That’s a good one Tim! I think organisation is key. There are bound to be influences that I’m not even aware of and if I dig deep, I think probably relationships and sort of strength, and nothing to lose. That’s the only word I can find really. I’ve often thought of landscapes a bit like interior design, that’s the only analogy I can think of. Where something looks good if it’s got something else to support it. That probably does go back to the theatre and set design.

TP: It does seem like an interior design/set design and lighting balance in a closed space.

CW: I think you’re right, and another element is that I’m incredibly untidy. I’m a horror story, my office is untidy, and I think I can just about close the drawer if I take something out of it, but not all the way! I’ve often thought why does everything have to be completely tidy in a photographic composition? Why am I so intolerant of something that I find is slack or not tight? Perhaps I need to see somebody in a white coat.

I also want the landscape to present itself, in what I say is one of it’s best performances. I’m not very good with any aberrations or any wonky bits!

TP: Can’t get the makeup artist in for the landscape can you!

CW: No you cannot! I enjoy that and I often walk away from something that I can’t make right. Even before Photoshop or anything it’s probably one of the reasons that I’m not good at Photoshop and I think it’s a wonderful tool but we don’t want to go off the point of composition. There’s something hugely rewarding in that, to be gifted something that you’ve come across and you’ve organised by being there at the right time, right place, all that stuff. That’s a huge joy as opposed to saying, “I’ll put another sky in.” I think that I care about a lot, but that’s not to be disdainful of anyone who uses Photoshop as it’s a wonderful tool. But from a compositional point of view, I like it to be tight and to make up for my terrible, personal untidiness.

TP: If you look back at what books or magazines that you would have read at the time, what would have been your visual influences or were part of the visual environment you were in. What books or paintings would you have been looking at?

CW: That’s fascinating. My mum used to say, you ought to know about painters and I used to say “I don’t know anything about painting”. I left school when I was 16 years old and only took one O’Level. Never went to university, never went to galleries, and my mother was very encouraging. She said I ought to go to gallery and study classical artists, the way they use light and form, shape, design, pattern, colour, dimensions and relationships, geometry and all of these things which are integral to landscape photography. I did go but not enough and I’m still probably not doing it enough.

As far as which artists, there is French painter called Claude Lorrain. I never actually knew much about him, but I started thinking how the usual suspects such as Constable and the likes, were absolutely skillful they were in working with light and producing a sense of three dimensions. I think I ought to do more, and I should go and see more of Claude Lorrain’s work. I felt you could step into his photographs and you know the far distance is about a mile and a half away and the skill to do that. So I’m probably subliminally influenced but I am by absolutely everything.

TP: Talking about subliminal influence, I presume you enjoy seeing movies, seeing films?

CW: Yes I really do and I think we’re influenced by what we see on television too.

TP: Cinematography is obviously a classic influence on most people, which movies were you enjoying at the time?

CW: I think I’d seen Casablanca ten or fifteen times! I can’t deny black and white resonates hugely with me. It was all 30s and 40s, Humphrey Bogart and all that crowd. Spielberg and all his lighting and cameramen, and some of the editors. That’s another person who’s the unsung hero. I’ll never forget years ago I went to see, Richard Attenborough doing a talk about Ghandi and I asked a really crass question “What role does the editor play in the construction of the film?” He answered very gracefully, he said “Probably more than the director”. I thought that was a wonderful piece of honesty, so I love the way when you look at editing some of the black and white films. Double Indemnity, I can keep remembering just completely marvellous. Jimmy Cagney and all those sort of films. I think about them a lot and the lighting played such an important part and their technical equipment in those days wasn’t so sophisticated. I’m not sure that we’re producing movies that have such an immense power to them, that move and awaken things in the viewer as they did then. There is a big come back to some of those film nows. The British Film Industry is showing them an enormous amount and they are very quick clips now in some television you see now, which I don’t see much of and some movies you see, are very short on the particular scenes. David Lean said, "you savour, but don't linger". I think people would do well to come back to that idea.

TP: Long establishing shots, are some of my favourites in films.

CW: That's the word, establishing shots. I look back and some of those and I probably see Casablanca again, again and again. I don't know why I loved Double Indemnity so much. My knowledge of films isn't hugely extensive but the process of composition I think sometimes is really very elusive. What is it that stimulates you to stop and start the process.

TP: This was one of the questions I was going to ask. How much of you working is instinctual and how much do you think you are consciously making choices about line curve, intersection, etc.

CW: I think it's developed over the years. I look at some of my photography from quite a long way back and I have to say that I sometimes wince by noticing what I overlooked and now I'm now much more thorough. Now I think I probably do my absolute best to take in every single element of what I'm looking at. To ask myself whether it have any case being there or not. I do try and pare away, pare away, until I'm telling my story. That doesn't mean to say that it's going to be a series of graphic, geometric shapes. I do find myself thinking more over the years, I'm developing and I'm still short sighted sometimes though, I really am.

I was looking at one of my old pictures the other day and I thought “I didn't notice that”. I'm often saying to photographers about noticing everything! Absolutely everything. As well as being frozen by the beauty of what you're looking at or the magnificence of what you're looking at. So you've got that to deal with as well, you've got to convey something of your sense of wonder. Which I think most of us are all having at in a different way.

I have a phrase "just having a go" and to try and produce and image that evokes in someway our sense of wonder. I think that's probably it and I'm sure we'd all agree that's what we're trying to do. It's awfully difficult. I remember people saying in the old days "I hope that comes out".

TP: It doesn't matter how many pictures you end up taking though there's only one or two that really work in that way. If you go out and take three or three hundred, you nearly end up with the same amount in the end.

CW: How true!

TP: If you look at the pictures in the book for instance, were many of those were instant ‘snapshots’ of recognition or would you say a majority of them have had a while sitting working on them?

CW: I think the latter. I used to feel that unless something was presented to you on arrival or I call it “gifted to you”; unless you were offered this wonderful combination and configuration of light, shapes and all that stuff on arrival, you couldn't predict what it might become if graced by a particular lighting scenario. It was impossible to say if I come back at dawn, yes you can predict mist but you can't predict the formation of the sky and the roll of clouds which play such an integral part.

I think the days are gone where I've arrived and it's been bang on. I try now to think that the structure is there, and that's sound, and the shapes seem to integrate with one another quite nicely, so I'll come back and see it in various different lighting conditions. Some might be two or three, perhaps four times maybe, maybe five at the absolute most. Let's be honest, sometimes, you turn a corner and kapow! We all know that and I would be fibbing if I said it took me days and angst. Not at all sometimes, it's bingo.

TP: So this is like your set design. Your set design has been recognised, you're just waiting for the lighting crew to arrive to accentuate things?

CW: That's certainly true. We are so impressionable when we're younger, you're the product of your experiences. So I was very impressionable and I went into the theatre when I was 16/17 years old as an assistant stage manager. I was watching great Shakespearian productions and high end ones even in repertory theatre, which are the places I worked. So I was constantly watching actors and the way they moved, and again, always lighting. I can't emphasise that enough, that had a massive effect on me and probably my photography.

There's this huge school of though amongst non photographers that we meet so often. You'd laugh if someone said you must have a good saucepan as this food is amazing! Gosh your frying pan must be incredible, the gravy is out of this world! We don't want great accolades and pats on the back but I think a lot of us would like our audience to appreciate that we have refined our eye over, in case of some of our chums, 20-30 years or more. That's not come easy, we have tripped up along the way and composition of a photograph is tantalisingly difficult sometimes and sometimes it's just out of reach! You just want to put the lid on it and think, this is precisely what I wanted to say and do. I'm not saying we want to be given a crown to put on our heads to say how marvellous we are, but I think a lot of our audience perhaps aren't fully aware of the angst that goes on in trying to get parity in the result. To have parity with our artistic intentions, I find it still terrible difficult. I know if I asked you the same questions and our chums, we'd all say that it's not always laid on a plate.

TP: Talking about cameras, your camera of choice has been historically the Hassleblad, with its square format. How much do you think that format of square and the use of that particular camera type has influenced the way you work compositionally?

CW:

I was brought up in the New Forest and I was hopeless at photographing the forest, it was chaotic! I couldn't find anything, it was really difficult. Far to busy and frantic, all types of stuff going on. So I couldn't refine and refine, which I quite like to do. I think square made me take a particular part of the landscape and make a big song and dance about it. I know the square is coming back now quite a lot just as I seem to be doing quite a lot more conventional rectangular!

TP: Looking through the book you notice that you've used quite a lot of landscape orientation pictures and a few panos. Many photographers like to use this foreground/background composition, and you very rarely use that structure in a picture. A majority of your pictures tend to be distant and taken from a slightly elevated view point. I wouldn't say it's a formula that you use, but it's quite common.

CW: That's a rather good point. I don't use very long lenses so perhaps I do pick out things? But you're right, I'm often up a ladder, usually to reveal more plains if I possible can. I want to try and mitigate the two dimensional nature of photography. I don't like to block things, I'd rather reveal more than conceal more in a way. That's a good point!

TP: I was looking through the book and there are pictures like Sinalunga (page 81 in the book) that's got a foreground/background effect and obviously the lavender fields. But the lavender fields (page 125, Valensole II, Provence, France) is probably the only one where you've gone up quite close to things. Maybe the ">pumpkinsfrom a while back.

CW: I think you might be right there. I was was looking at Sinalunga and you're right. Down and up works quite nicely I think. That's a good point.

TP: I wonder if that's a symptom of that the Hassleblad not having so much depth of field and also the square format not trying to force a foreground. The upright portrait classically does.

CW: That's a very strong point. I'll buy into that idea. Sometimes it eludes me, sometimes we don't see squares. So it is slightly perverse to photograph something in the landscape with a square format. There weren't many lenses made for square, I think I there was a 40, 50 and a 150, 250 and that was it.

TP: You obviously shot with a 6x17 occasionally as well.

CW: I did, how scary, what a beast!

TP: With digital cameras now you have probably normalised to a 2:3 ratio. Do you photograph to crop ever or do you always use the aspect ratio of the camera?

CW: I think the latter. I don't think people should be forced into it. A lot of people probably are. Perhaps some are able to look through and think I'll crop that out later and I'll tighten that up, and I'll take a 1/15th of the image off there. I think the discipline of trying to fit, so there's not a lot of post cropping. Might have been once or twice.

TP: It's difficult to visualise the edges of a picture when they are not actually there definitely.

CW: Isn't it just! You're quite right. You know we say that that we used to say that only 98% of what you see is there in the viewfinder. Is that all sorted out now with digital?

TP: Yeah on digital it is I think. Mirrorless is perfect, as you're seeing the final picture of course. I think on some of the SLRs they are pretty close, they aren't far off these days. Still the range finder cameras, the digital range finders can be off. I tend to use a mirrorless camera.

CW: I'm tempted, I'm just waiting for a Hassleblad back to come back, the CFV50C. What a name for a bit of equipment!

TP: That with a camera looks absolutely extraordinary. We had a chat with Paula Pell Johnson at Linhof Studio back in June with Joe in a podcast. We chatted about what was exciting coming up in gear and Paula said the most exciting was the new Hassleblad digital back that fits straight onto the old Hassleblad camera and also had it's own little mirrorless SWC type camera as well. That should be interesting.

CW: And a special battery for it, and you have to get a special adaptor. If you're talking about the one which came out a month or two ago, with the hinged view finder. I'm hoping my friends at Hassleblad might find themselves sending me one! Not yet! It's the same mega pixel count

It delivers a hell of a good image I must say. I didn't think, I ought to have looked at the lenses as there were times when I thought about the old Hassleblad lenses. I know we're going off piste a bit! I thought I better check up as I was using lenses which were 30 years - 40 years old! The SWC body which has a fixed 38 on it and the distagon lens which I've got. I thought that perhaps I wasn't getting the best resolution and honestly when I look at my transparencies which I still do a bit of, I think that I'm alright. Even going up to some fairly bit size 4ft or so I think I'm alright. It's good to hear you say that the lenses are still good on the old Hasselblad system, as I feel they are!

TP: Still one of the best lenses I've ever tried is the last Hassleblad lens, the CFE 40mm, the very large 40mm.

CW: I'm so glad you say that, I think so too. I'll stay with it then! If my friend Tim says it's alright then it is! I'm glad you say that as I do worry and think Charlie you better check, you're behind the times!

TP: I was going to ask you, do you think you can get the landscape photographer of the year exhibiting back at somewhere like the National Theatre?

CW: How funny! That's an extraordinary question because I was talking to the head of publisher at the AA who are going to do the next book and that's exactly the question he said. Because he said yes it was elitist at the National Theatre, yes not everybody could go and see it, but the setting for the exhibition was hard to beat and also 35,000 people, you can't always that number to come into even The Photographers Gallery over an eight week period. That's the what we could enjoy, especially if they play had three intervals!

TP: I thought it was the best place for an exhibition I've seen.

CW: I couldn't agree more. I have to thank the guy behind it who was the unknown figure called John Langley, who's retired now. He wasn't front of house manager, he was much bigger than that. He loved photography and he mounted 160 photographic exhibitions during the time he was there. He was an extraordinary man, he gave me three exhibitions at the National Theatre. I'd rather be there than anywhere else, so I'm glad you say that, as it's a mixed audience, and you're introducing photography to people who would have never thought of going to a photographic exhibition. So it met with a really wide audience. To answer your question, I'm hoping we can! That's not saying that Network Rail do make it less London centric which everyone said is that it had to be in London, and said get it up to us! So it goes to twelve stations and I'm thankful for that and we are running again.

The website is being done by the people who do the Sony World Photography, the same group More Wilson in Salisbury, down the road!

TP: Two more questions for you. How much influence do you think the camera you use, I.e. the shape, the haptics etc, influence your picture generation? I'll give you an example, the use of a waist level view finder on the Hassleblad vs a SLR through the lens view or a heavier camera.

CW: Looking down as opposed to looking across. Well I think. It would be fair to say I remember talking to Joe about this. That when the great Ansel Adams and his 10x8 and even before then the whole plate and half plate, I think you could study in-depth from right to left and top to bottom. All the integration of what a photograph is of all the different elements. I think it was a bit like going to movies with a 10x8, and I've still got an old Gandolphi and I still enjoy that to look through it. I've actually found all the dark slides, and perhaps I should have another go!

Joe and I had an quite an in-depth conversation where you put your cloth over, you know this, and you're getting down to business. You can explore on that ground glass screen what you're about to make an image of. You're almost looking at a monitor. I do think being able to see more has a strong bearing on your powers of observation. They are enhanced by able to see more. That little view finder, I still think people shouldn't look at the LCD screen, but that's me old school. I still think looking at the back, unless you put a cloth over it, you totally exclude everyday life and look at it in that aspect.

I think the answer is yes, it does. The other thing is I really enjoy that machine, I enjoy holding it! I saw an old friend the other day who was in a MGB and he said that it's not that's it an old car, I just have had it for 30 years and I'm wedded to it. I can't give you a logical or rational reason why. It's like an old bed, or a good sofa. I think it does influence me a lot though and the process of using it.

TP: Like the mirrorless cameras, do you find yourself working differently when you're using those as opposed to a large digital SLR?

CW: Yes, only word I can think of it “reach”. I can't reach what I want to photograph. I find it rather difficult to explore. I don't want to have to enlarge up chunks of it and see it in isolation. Is that hedge got something out of it? Has that rock, has that field? The lichen seems to have changed colour half way through, wouldn't have noticed that so I had to enlarge it up. That's frustrating to always have to make it bigger. I'd rather have a loupe and do it the way I just described.

TP: Do you use a phone to take photos ever?

CW: Yes, I really do. Joe was so honest when we went up and I did a little chat up at the gallery. It was a lovely answer and it shocked people in the audience. Somebody from the audience said could I ask you Joe what his favourite camera, and he said quite rightly, yes, my phone! I love that about him you know, there are many lovely qualities about him that are enjoyable and I loved that he shocked people by saying that.

I think it's the most marvellous compositional aid. I wish they made the screen bigger. I think we would all be lying if we said we didn't use it.

TP: What aspect of using a phone do you like most? Is it the fact that you've a large screen to play with?

CW: That's hugely enjoyable, I still use my silly bit of cardboard though, 5x4 frame thing. It's about exclusion more than anything else. I think that the composition business is made hugely easier by that little simple thing of cupping their hands together that cinema-photographers do. What does it look like alone? What does it look like without the supporting bits? I think the phone is a really good adjunct to the conundrum of composition.

On all our Light and Land trips, you always say what's the thing that eludes you most. What's the thing that you find most tantalising and difficult - it's composition! If I haven't heard that a thousand times. We're all finding it elusive.

TP: Final question then. You mentioned slack in pictures. Getting rid of the slack. Can you say what you mean by slack or give us a few examples of what it might be?

CW: I think the only way to describe it is... it's hard to articulate isn't it? I think interior design is probably the best analogy to use as you walk into somebodies house and you think, nothing goes with anything. It's an aesthetic minefield of a disaster. You just don't feel comfortable.

When you look at a shop you're often drawn into it because of the exceptionally stylised window display. I sometimes look at fashion and I'm not a fashionable person, but I look at the clever way women's clothes are designed. I find myself thinking how well organised that is, not just the cloth but the pattern.

So slack is where there is insufficient attention to detail. Other people might like lose and I used to think a single blade of grass unsharp and effected by wind movement was unacceptable. So I had to put a roll of 400 in, as it was just not on.

All of a sudden I find myself saying, snap out of it Charlie, a bit of grass moving is totally OK! On the whole, I think all this goes back to your very first question about that stage set.

A presentation, and I still think of it as a production and I think you probably agree, a photograph is a technical term but it's a production made up of so many different things going on. Once you start getting obsessive about it, which is what it is, I find myself not being able to tolerate something which is any way lose.

Yet, I still look at results and think for god sake Charlie you didn't see that!

TP: Thank you so much for that Charlie.

- You can buy the hardback book from Charlie's website for £35. (click here for details).

- Also see the recording of Charlie's lecture at our Landscape Photography Conference 2018.

- The interview with Charlie Waite and Graeme Green