A practical guide

Theo Bosboom

Theo Bosboom is a passionate photographer from the Netherlands, specialising in nature and landscapes. In 2013, he turned his back on a successful legal career to pursue his dream of being a fulltime professional photographer. He is regarded as a creative photographer with a strong eye for detail and composition and always trying to find fresh perspectives.

Introduction

Recently, as a member of the jury of the Natural Landscape Photography Awards, I had the opportunity to judge a large number of landscape photographs and also a large number of projects. Although we sometimes had firm disagreements within the jury, we were in full agreement on one thing: the number of really good projects was quite limited. That observation dovetailed perfectly with my own findings as a workshop leader and photo coach. For years, I have been running a workshop called My Project, in which five photographers work on a self-selected photo project for a year under my guidance. Time and again, it turns out that photographers find this very difficult, even experienced photographers who are capable of making great photos. The individual photo coaching I give to photographers shows the same picture. Apparently, realising a good project requires more than just photographic qualities.

In this article, I will try to give some tips and guidelines for working on projects. This need not necessarily be a project for a photo competition like the NLPA, but it can also be a project that culminates in a series of images for a magazine publication or an exhibition. You could also think of working on your own photo book as a (comprehensive) photo project, but this again has its own dynamics and peculiarities and is thus perhaps more suitable for a separate article.

Before I go any further, I think it is good to briefly describe what exactly I mean by a photo project. A photo project is a process in which the photographer works towards a goal within a certain period of time, realising a photo series within a certain theme. This theme can be very different even within landscape photography. It can involve a geographical area (e.g. Death Valley or Iceland), a specific habitat or type of landscape (e.g. the coast or mountain landscapes) or zoom in on parts of the landscape (e.g. trees, waterfalls or rocks).

Thereby, it often works best to define the theme as well as possible and not make it too broad. So not the theme 'nature' or the theme 'landscapes', which is too broad and therefore too meaningless.

A project series is not the same as a portfolio. The latter, too, is a collection of images usually made by one photographer and, therefore, will also show a certain unity if all goes well, but the images are usually made in very different places and at different times and often have no thematic connection to each other. It is usually a collection of the photographer's best images, a showcase of his or her abilities.

A photo story also falls under photo projects, but a photo project does not always result in a photo story. You can also have a photo project with no real storyline or a story that is too limited to count as 'storytelling'. This is probably true of most projects within landscape photography. By the way, there is no very clear demarcation; there are grey areas.

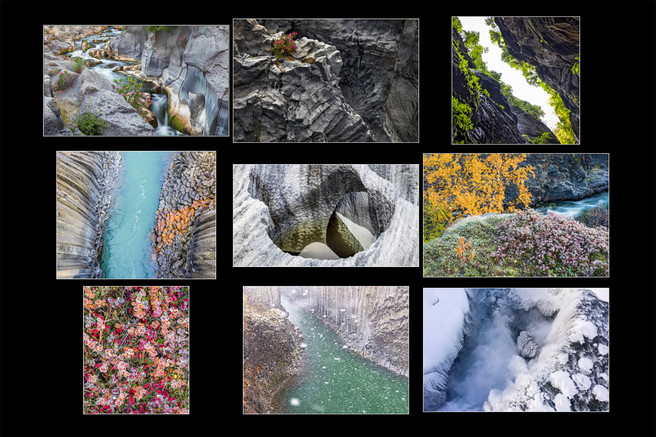

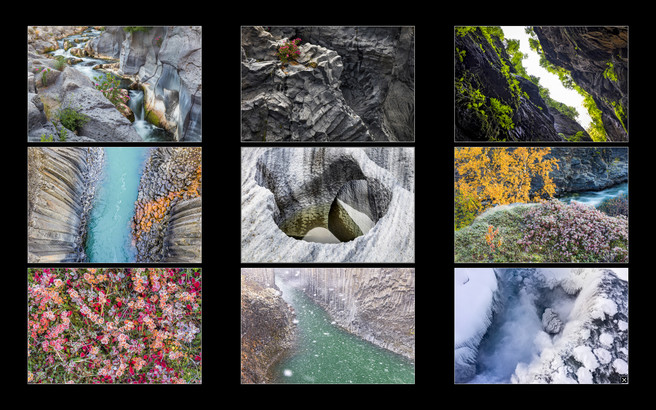

If you compare the grid view of my project submission for the NLPA last year about European canyons with a fictional second edit of these images with all kinds of different image ratios, you can see the benefits of limiting yourself to one image format. The first set of images looks more balanced and pleasing.

Why Projects?

Why should you work on projects as a photographer? Doesn't it create too much of a straitjacket that restricts creative freedom? This is not the case for me, and for many other photographers too, at some point, it feels like a logical step in their development to start working more focused and project-based.

I myself find it very enjoyable and enriching to work on a project basis and do not experience it as a creative restriction at all. On the contrary. The different requirements involved in delivering a project have made me look at things differently, and I feel my photographic horizon has broadened. In addition, it gives me peace and focus. Before I still often wanted to do everything at once on a beautiful morning in the field (landscape, wildlife and macro), but now I can focus and limit myself better and that generally produces more compelling images. Finally, I find the additional aspects of project-based work - i.e. the things besides the actual photographing - fun and challenging. Think of coming up with and working out themes, doing research on subjects and areas, writing accompanying texts, selecting the series from the available images and presenting the final result. You can put a lot of yourself into this and thus make it very personal.

Working in projects is also important if you want to increase or establish your name as a photographer or if you want to start working as a (semi-?) professional photographer. Good photo series on a specific theme or area are more interesting for magazines, presentations and exhibitions. And whereas you can generally only apply once to a particular magazine with a portfolio, this limitation does not apply to photo series from projects.

The Start

You can start a project in many ways. Some photographers think of everything in advance at the drawing board and know exactly what images are needed and where and when they are going to shoot them. Some even create mood boards for the intended mood and colours of the photo series. Other photographers, like me, take a somewhat less planned approach, especially at the start of a project.

Sometimes you decide that there might be a project in there somewhere after you have taken some good photos that fit within a theme. I once wanted to take a wide-angle macro photo of limpets in their habitat, so for a while, I was very focused on these creatures every time I was photographing on the Atlantic coast. Once I was able to take the photo I had in mind, I was now so fascinated by the subject that I decided to turn it into a project. It usually starts with this kind of fascination with a place or subject. And you often need this fascination to bring a project to a successful conclusion because it often requires focus and perseverance after all. When looking for a suitable theme, the first question could therefore be: what do I like to photograph most?

If you then have one or more possible themes, it might be useful to check whether there are already good photo series on the same theme. This is not so important if you are doing a project purely for your own photo enjoyment without much further ambition, but it is if you want to stand out with the project and perhaps publish the series or submit it to a photo competition. For instance, I myself once had the plan to do a photo series on the ‘Dutch mountains’, depicting artificial mountains made of rubbish, sand and gravel etc., but it turned out that such a series had already been made several times before. Of course, you can always see if you can really add something with a different angle, but if that is unlikely, you would be better off choosing a different theme.

I really liked this dramatic seascape of the Spanish coast, but my editor Sandra Bartocha and me agreed that it didn’t fit into the more subtle and intimate language of my Shaped by the sea project

Once you have chosen a good theme, try to describe and delineate it as well as you can. This can help you to be as focused as possible, and sometimes it can put you back on track later if you have stalled for a while with the project. A good description is also needed once the project has been completed so that it can be properly presented and possibly published.

Besides choosing a theme, it is good to ask yourself in advance what kind of project it will be. For a Storytelling project, you simply need different images than for an artistic project with purely abstract images. Also, ask yourself what the intended audience is, as this can also influence the photography and, later, the selection and presentation of your series.

It can also be useful to make a (rough) schedule for your project, especially in case certain images are seasonal (think images with snow or ice). Finally, it is advisable to take stock of whether you need a permit or cooperation from other parties for certain parts of the project. Sometimes it takes a long time to obtain that permit or cooperation, and it is a shame if your project is delayed or comes to a standstill as a result.

The execution: photographing, evaluating and making adjustments if necessary

When photographing for the project, it is important to look ahead to the desired final result. Ideally, the final series should contain a good mix of unity in style and theme on the one hand and sufficient variation in the images on the other.

This abstract image taken in a Norwegian canyon makes a welcome change among the somewhat wider and more literal other images in this project

The unity in style can be achieved, for instance, by choosing in advance a fixed image format (e.g. 3:2, 1:1 or 16:9) and between colour and black-and-white. It can also help to shoot at the same times of the day or consistently in certain light. After all, you don't want your final series to end up shooting all over the place in terms of style and presentation. By the way, later in the project, when editing and selecting, you can also ensure as much unity as possible. How you proceed is a bit personal and also depends on the type and size of the project. If the goal is a tight series of eight to 10 images, unity in style is more important than when you need to deliver 50 photos for an extensive reportage in a magazine.

On the other hand, variety is very important. If, after 3 to 4 images, people think they have seen the whole series, they will drop out. So you will have to keep your audience interested, whether it is a magazine editor, a jury of a photo competition or a group of people attending one of your lectures.

Fortunately, there are all sorts of ways to achieve the desired variety. As a photographer, you can use your full technical and creative toolbox and vary with angle of view, composition, depth of field, focal length, light and dark, static and dynamic images and so on. In addition, think about content variation. Try to capture different aspects and features of your chosen area or subject. If you want to tell a story, make sure you capture the essential elements in your story. Try shooting in different weather conditions and going out in the evening or at night.

What always helps me personally is to regularly evaluate the images made so far. Make folders with usable images and maybe even the start of a series, and look at the images individually and as thumbnails, for example, in the grid in Lightroom. Also, ask for specific feedback already at an early stage because now you can still make adjustments and possibly create additional images. Check if your intentions come across and ask if there are any essential things missing in the series. In addition, receiving feedback can be motivating and inspiring.

Although this image of a limpet is a welcome informative image in a broader series for a magazine, it wouldn’t work in a project submission with the theme Limpets in the landscape. It is too different from the other images and the quality is not good enough.

The final phase

In the final phase of a project, it is good to take stock of which essential images may still be missing so that you can try to make them and add them to the collection. You can distinguish between essential and 'nice to have'. Personally, I find that I often take a much more targeted approach in this phase of a project than in the beginning and that I usually set off with a wish list. For example, my project on European canyons is currently missing good footage of a raging river rushing through a canyon with great violence after the snow melts or after heavy rainfall. I find this so essential for my project that I will try to plan a dedicated trip to take such pictures.

It is often difficult to determine when a project is complete. The problem with many photography projects is that, in theory, you can keep working on them endlessly. There will always be photos that are still missing or that could be better for your liking. At some point, you have to put a stop to it anyway and move on to something else.

Once all the images have been made comes the final and perhaps trickiest phase for many photographers: making the final selection. I have heard that photographers at the US edition of National Geographic are asked to submit all the images (all the raw files) taken on a project, even if there are 300,000 of them! This is based on the idea that photographers are bad at selecting and editing their own work.

In any case, it pays to ask other people for help. These may be one or more experts, but sometimes I actually submit series or images to my children, who are not hindered by photographic knowledge and experience. Their primary reactions also provide valuable insights for me. The most important thing you can learn from other people's opinions is how your work is viewed without the emotional involvement and memories of the moment that you yourself carry with you. Many photographers tend to rate higher photographs they have had to work hard for. But for the public, it is usually not apparent whether you have taken a particular photo from a car park or after a 12-hour mountain trek, wading through three rivers and covering 2,000 altimeters with a 30-kg backpack on your back. One simply looks at whether the photo appeals or not.

When selecting, don't just look for the most spectacular and impressive images, but try to achieve a balanced mix in which some more subdued images also have a place. Just as a football team with only Messis usually does not work, a photo series also benefits from water carriers and quiet forces that make the whole stronger. However, there should be a lower limit to the quality of photos: images that have significant flaws in technique or composition do not belong in a series either.

For a magazine, it is usually slightly easier to make a selection than for a photo competition, simply because you can use more images. The photo editor of a magazine then chooses some images from a wider selection. When I offer a series to an editor of a magazine, I usually send a series of 20 to 30 images. Sometimes additions or a wider selection are requested later (depending on the size of the publication).

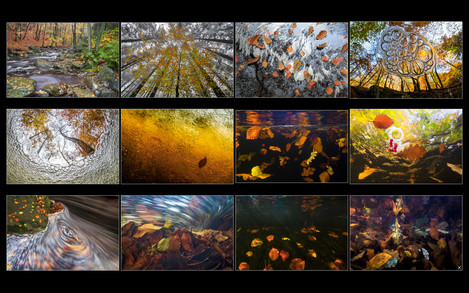

Some images of my most published project so far, the journey of the autumn leaves. The originality of the theme was an important factor in the success of this series.

10 tips

Finally, here is a list of specific tips for photographers considering submitting a project to the NLPA or other photo competitions next year:

- Consider a project close to home. This year's NLPA edition reaffirmed that choosing an exotic destination far away does not necessarily make a series better. A project a little closer to home offers the advantage of being able to work on it often and easily, while also benefiting from knowing the area well. Of course, it is also better for our planet if photographers do not travel as far for their projects.

- Before you start, check that your theme is not too hackneyed, the more original the better. And if you do choose a familiar place or theme, try to put your own spin on it and make it personal.

- Do not submit a project until it is really ready. So be patient!

- Also assess the selection as a whole, i.e. with all photos at a glance, for example in the grid in Lightroom or with separate small prints that you put together. This allows you to see at a glance the coherence and variety of the series.

- Try to choose images in 1 image format (e.g. 3:2, 1:1 , 16:9) or at least limit the number of image formats to 2 or at most 3. This makes the series more coherent and more pleasant to look at. If you have to crop images, do it with locked aspect ratio so that the proportions remain the same.

- Enlist help in making the final selection, preferably from several people. When doing so, ask for targeted feedback, so not just whether one likes a series or not.

- Less is more. Several wonderful projects submitted this year did not make it in the end because there were a few weaker images in the selection. Many photographers opt for the maximum number. Sometimes, however, it makes more sense to keep the number of images limited. Better to have seven images that are all good, than 10 images of which seven are good and three are mediocre. In any case, try to avoid duplicates in your series, two or more images that actually show more or less the same thing.

- Kill your darlings. It is sometimes very hard to leave out a top photo you are wedded to, but if it is better for the whole, you just have to do it. If necessary, just submit the photo in question as a single image in another category.

- Pay enough attention to your project description. For many photographers, this is a job that is quickly done at the very last minute, after the images have already been uploaded. However, the text can be an important addition and can partly determine how your images are viewed. Especially with a more narrative series, this is very important. Often images and projects gain more meaning when you find out more about the backgrounds of the subject and also the motivations of the photographer.

- Pay attention to your edits! In a project, all photos in the series must comply with the rules of the NLPA. This means that all photos must therefore be carefully checked before you submit them.

Finally, don’t forget to have fun while working on your projects!