Resonance and learning how to see

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

It is not reality that photographs make immediately accessible, but images.~Susan Sontag

Transfixed by our technologies, we short-circuit the sensorial reciprocity between our breathing bodies and the bodily terrain. Human awareness folds in on itself, and the senses – once the crucial site of our engagement with the wild and animate earth – become mere adjuncts of an isolated and abstract mind bent on overcoming an organic reality that now seems disturbingly aloof and arbitrary~David Abram

There is a theory that the separation of man from nature was driven by the invention of the alphabet and phonetic writing1. Early forms of writing were pictorial and retained some symbolism of nature, but the Greek alphabet removed nearly all such references (even if we might still be able to perceive the origins of the Greek α (and our own letter a) in the Sumerian pictogram of a cattle head with horns, later turned on its side). As a result, nature became more remote, less directly experienced, and the animist beliefs that are common to many pre-literate societies (to this day) started to gradually fade away for the majority2. Indeed, from there, it was only a short evolutionary step before hundreds of climate scientists were taking long haul flights to discuss the climate crisis; the presidency of COP28 was being given to the head of a major oil company3; 0.6% of global energy resource was being used to support imaginary cryptocurrencies4; and the deteriorating landscape could be photographed at 100 Mpx and up to 400 frames per second5, only to be mostly shown on low resolution screens.

Animist beliefs often include the idea that nature is watching human behaviour and is thus to be sustained and protected. That separation, however, eventually led to nature becoming something to exploit: for agriculture, for minerals, and as a means of cheap disposal of wastes in rivers, seas and the atmosphere (as is still, appallingly and unforgivably, the case for the privatised water utilities in the UK who are giving more in dividends to shareholders than they plan to invest to improve the situation6). Developing technologies, from the printing press to the internet, have only made this separation greater. The air, in particular, once an important source of information about the environment around us, has become almost invisible, despite the fact that it is now a source of fine particulates, viruses, and fungal spores that can affect our health and aging (though a bit of particulate pollution, of course, will often help produce dramatic colours in sunset images7).

In the world of modernity the air has indeed become the most taken-for-granted of phenomena. Although we imbibe it continually we commonly fail to notice that there is anything there. We refer to the unseen depth between things as empty space. The invisibility of the atmosphere, far from leading us to attend to it more closely, now enables us to neglect it entirely.~David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous

Our experience of nature has consequently become less immediate and much more influenced by technology in what we read, the images we see in reproduction, and the cameras we use. Susan Sontag (1933-2004), in her book On Photography, which first appeared in 1977, explored this idea in some depth. She suggested that the separation from nature provided by the camera was a way of assuaging any anxiety we feel about being in unusual locations (especially as tourists) for two reasons. The first is that when we are taking photographs, we are normally not at work, but photography acts as a form of work to assuage our puritanically-influenced consciences (for those from certain traditions, at least). The second is that photographs are a way of taming the unusual by capturing a moment in time and space. That time and space then become part of our collection of memories as represented by images8. Indeed, she later suggested that such images were replacing memory as a rather poor substitute for actual experience. The camera is an easy option to prove that we were there; one that stores away that experience in a way that, in principle, we can come back to at any time (though with the increasing number of images we do store away, finding them again might be a challenge, and losing them to disk failures etc a real possibility).

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it – by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs. ~Susan Sontag, On Photography

Of course, having read Guy Tal and other articles in On Landscape, most of us accept that photographs do not represent reality (they perhaps become real objects only as prints or books when they serve as an approximate, one step removed, representation of real experiences). But philosophical debates about the effects of technology on experience go back to before photography had had a real impact - at least to Søren Kierkegaard in the 1840s. The technology then was the telegraph, bringing news of far-flung places faster than ever before, changing the nature of how people at that time experienced “news” (compare with now when news and fake news arrives almost continuously, even while we sleep).

But once photography took hold, the impact of images of remote places and people was perhaps even greater. People we had not met and places that had not been visited could be visualised for the first time (the impact on the creation of the first national parks in the US, for example, is well-documented9). It was in the 20th Century that this mediation of reality on experience by technology was considered in more depth, particularly by the philosophers known as the phenomenologists. Phenomenology is the study of the structure of individual experience. That experience can include our immediate sensations, but the experience is often wider than just sensations when they interact with the conscious mind. Clearly, our cameras mediate that experience, including the ways that Sontag identified. The question is perhaps a little more complex than that, however (but we are talking philosophy here – so it is always more complex than that!).

In this context phenomena are things that we consciously recognise (objects, feelings, emotions, ideas, landscapes). Phenomenology is the study of how and why we consciously recognise those things. There may be other things that (literally or effectively) we respond to only subconsciously, so one of the key concepts of phenomenology is that of intentionality, of conscious recognition.

This is a subject that has interested philosophers since the Greeks, but the modern study of phenomenology started with Edmond Husserl (1859 - 1938), who first used the term in his book Logical Investigations (1900-1901). He defined it as the science of the essence of consciousness approached from the perspective of the individual. The theme was then taken up by others, including Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1976) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), and at least 7 variants of phenomenology were recognised in the Encyclopaedia of Phenomenology published in 199710. The philosopher of most interest to the phenomenology of landscapes is perhaps Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) who published a book on The Phenomenology of Perception in 1945 (originally in French)11. More than the other phenomenologists, Merleau-Ponty engaged with cognitive scientists and psychologists of his time, creating an early foundation for some modern theories of mind. He also stressed the importance of subjective perception in consciousness and the individual experience of a reality. It is important, in his view, to consider perception as felt from within the individual, not as an external intellectual construct.

Insofar as, when I reflect on the essence of subjectivity, I find it bound up with that of the body and that of the world, this is because my existence as subjectivity [= consciousness] is merely one with my existence as a body and with the existence of the world, and because the subject that I am, when taken concretely, is inseparable from this body and this world. ~Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception

In the view of Merleau-Ponty, any art is a means of trying to capture the perceptions of an individual12. The interaction of that individual with his or her surroundings is fundamental to that perception, including elements of the history of the culture that individual lives in. Viewed from within13, we are shaped both by our sensual experiences of things and our history, including our use of language, but often independent of any verbal awareness.

Which brings us back to the alphabet and how technology may have shaped our perceptions of nature away from direct sensorial interactions that our ancestors needed to be learn how to interpret; to something more remote, mostly learned from books and images. Our phenomenology of experiencing the landscape has changed with the technology. Looking at the landscape through a viewfinder is a quite different experience to making inferences from the sounds and odours brought to us on the wind. Of course, some of us still learn to recognise bird song, identify the trees and flowers associated with different soil types, or interpret the coming weather from the cirrus or cumulonimbus clouds in the sky. Some of us are lucky enough to learn such knowledge as children from parents and elders, or later by teachers who know a lot about the science of the environment including knowledge that we cannot directly sense for ourselves (chemical and isotope analyses, genetic sequencing, microbial and fungal populations, remnant magnetism, thermoluminescence and so on). Technology has thus also provided greater depth of knowledge of the landscape, even if there is much that is not yet properly understood or part of a history mostly lost to us in an unrecorded past. Much of that knowledge is captured now by written text and images and available by searching in cloud land.

But we have also lost something. We are sometimes exhorted to put down our cameras and just experience what is happening around us, to repress the urge to take or make an image and “reconnect with nature”. Such a suggestion implies that some phenomenological connection has been lost, that the camera imposes a disconnection from the real experience, a barrier between us and the essence of the wonderfully multifaceted landscape. That is surely true to some extent in all photographers. At one extreme, it is evident in the selfie image, which requires facing away from the landscape. But is also the case whenever we are at a classic location, worrying about whether we will be able to capture a classic image with a collection of past images in our mind rather than the landscape as it is in front of us (and therein lies a road to disappointment for many).

But if phenomena are our conscious, intentional recognition of sensations, both external and internal, we can be proactive in seeking out those sensations that resonate with us while out in the landscape. This idea of seeking resonance has been expressed by the sociologist Hartmut Rosa as a way of reacting to the acceleration of many aspects of modernity14. While he explores the concept of resonance more in relation to other people, society and politics, he also discusses resonance with the landscape and environment. He points out that there is a resonance with nature in the modernist tradition, stemming from the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, that is irreconcilable with the capitalist utilisation of nature as a resource to be exploited. He cites Angelika Krebs in support of the idea that it is a sphere of resonance with nature that provides a rational for sustainability15, but is concerned that this is currently too one-sided – it is resonance as aesthetic contemplation, a sort of leftover from the concept of the sublime in Edmund Burke.

As photographers, separated from nature by the viewfinder, we are often participants in such a one-way process. We may feel some resonance. Some locations and conditions might resonate more than others, and there may be the element of surprise, luck or a chance phenomenon that suddenly enhances that resonance (see the sun halo below from a recent snowshoe walk). In the same way that we are individual in our response to phenomena, so we are individual in our capacities for resonance with phenomena we encounter (and with the camera systems we use, some being more satisfying than others). But even if we are more likely to contemplate, to slow down, to take time, to find satisfaction, and enjoy a process and scenes that resonate with us, we will often remain observers, one step removed, concentrating on the viewfinder, concerned with our art, when there is so much other feedback from nature to respond to.

There is, however, another side of this aspect of being a photographer that can have benefit in our interactions with the phenomenological landscape. A camera is a separating device but also a means of focusing our attention. It involves intentionality in creating an experience (and hopefully a satisfying consequent image) as well as just being conscious of phenomena. In making a composition it is a way of learning how to see certain aspects of the landscape that might otherwise be overlooked16. We become more aware when we have the intentionality of looking for potential images. Occasionally there may even be the resonance of being “in the zone” or experiencing “flow”. There might still be much that we miss but growing as a photographer is a reflection of that learning process, perhaps also carrying some side benefits in increasing our depth of knowledge about interpreting the natural world. We may not get back anywhere near to the skills of our pre-literate ancestors in being able to infer information from our sensations, but we can surely be proactive about wanting to know more about what we see, hear and feel in the landscape and about wanting to protect it.

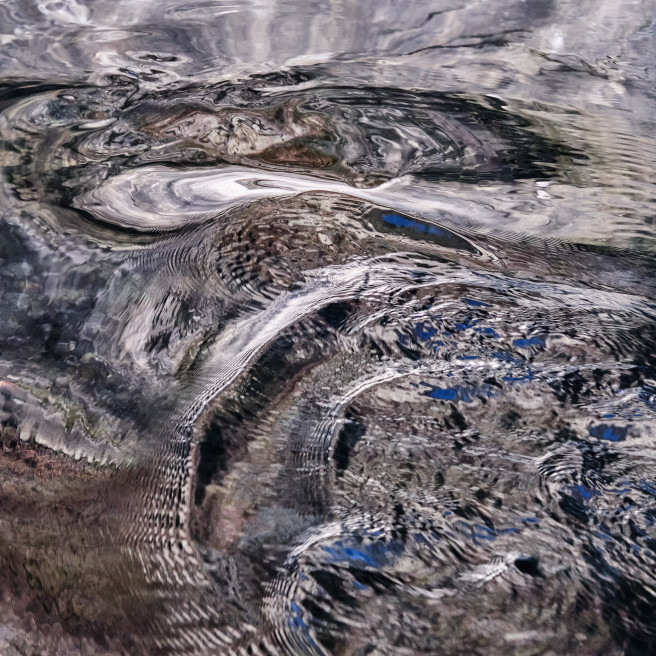

Reconnection with the landscape, dynamic light reflections, Hauterive #1, Switzerland, February 2022

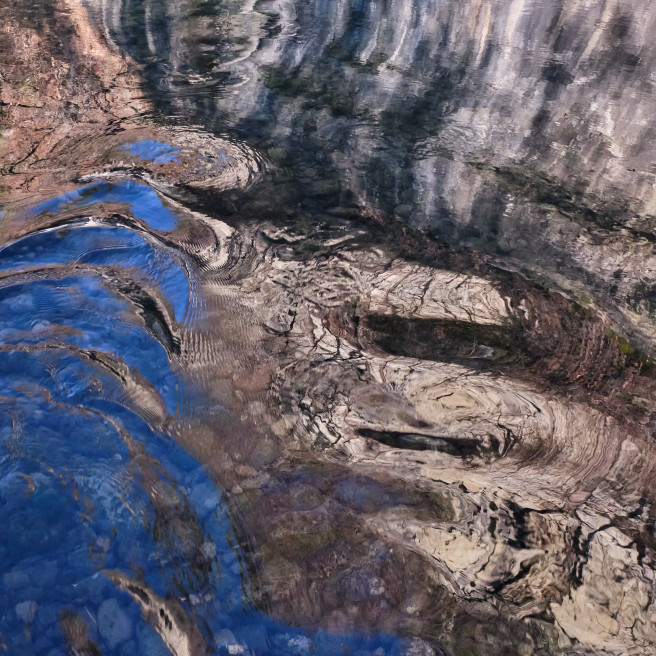

Reconnection with the landscape, dynamic light reflections, Hauterive #2, Switzerland, February 2022

Reconnecting with the Landscape, the sound of running water, Hauterive #3, Switzerland, February 2023

References

- Partly, of course - see, for example, David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous, 20th Anniversary Edition, Vintage Books, 2017. Another theory, mentioned in passing in the Hartmut Rosa book below, is that it started earlier when humans first started to wear shoes.

- In an Afterword added to the 20th Anniversary Edition, David Abram writes: “In the absence of intervening technologies, sensorial perception is inherently animistic ….our sensing bodies cannot help but experience the other bodies that surround – not only other animals and plants but mountains, gushing rivers, buildings, thunderclouds and even the gushing wind – as open and enigmatic powers”

- Sultan Al Jaber of the United Arab Emirates company Adnoc, see https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/14/uae-running-towards-renewable-future-says-oil-boss-cop28-president

- See https://ccaf.io/cbeci/index

- As in the Fujifilm GFX100s, https://fujifilm-x.com/global/products/cameras/gfx100s/specifications/

- As recently reported in the Guardian at https://www.theguardian.com/money/2023/may/20/the-whole-thing-stinks-uk-water-firms-to-pay-15bn-to-shareholders-as-customers-foot-sewage-bill

- And it has been speculated that the dust from volcanic eruptions has had a significant influence on the paintings of artists, including J M W Turner, and later following the Krakatoa eruption, Edvard Munch’s The Scream (albeit painted later from the memory of the skies in Norway following the eruption). The British artist William Ascroft also left a whole series of pastel sunsets over the Thames at Chelsea following the Krakatoa eruption – see https://hyperallergic.com/173597/clouds-like-blood-how-a-19th-century-volcano-changed-the-color-of-sunsets/

- Remember the days of enduring family slide shows, anyone?

- See, for example, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/how-photography-shaped-americas-national-parks-180959262/

- And, more recently, at least 4 types of Speculative Realists, highly critical of the Phenomenologists (see Graham Harman, Speculative Realism, Polity Press, 2018)

- There appear to be two English translations available, from 1996, translated by Colin Smith and from 2012, translated by Donald A. Landes, both published by Routledge.

- He thought that science was the opposite of art, an abstraction that neglects the subjective profundity of any phenomenon that it tries to explain. He suggested that, therefore science cannot provide complete explanations of the world.

- An interesting take on the view from within was provided by Thomas Nagel’s 1974 essay “What is it like to be a bat?” published in the Philosophical Review.

- Hartmut Rosa, 2019, Resonance – A Sociology of our relationship to the world, Polity Press. Rosa’s argument is that resonance is more important than simple monetary resources in our finding satisfaction and happiness, and that different people will have different capacities for resonance (either with the natural world or with other people and society) that has a fundamental effect on satisfaction and happiness. He writes: “It is rather the result of a relationship to the world defined by the establishment and maintenance of stable axes of resonance that allow subjects to feel themselves sustained or even secured in a responsive accommodating world”.

- Krebs, Angelika., 2014. Why landscape beauty matters. Land, 3(4), pp.1251-1269.

- See, for example, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/12/interpreting-the-found-abstract/ and A little piece of Eden articles

- Landscape Alienation, Hauterive, Switzerland, February 2023

- Phenomena: Perceptions and intentionality, Aureid, Switzerland, February 2023

- Phenomena: Perceptions and intentionality, Aureid, Switzerland, February 2023

- Phenomena as chance, Euschelspass, Switzerland, January 2023

- Reconnection with the Landscape, Euschelspass, Switzerland, January 2023

- Reconnection with the Landscape, River Doe tributary, Ingleton, January 2023

- Reconnection with the Landscape, textures and light, Morat, Switzerland, February 2023

- Reconnection with the landscape, dynamic light reflections, Hauterive #1, Switzerland, February 2022

- Reconnection with the landscape, dynamic light reflections, Hauterive #2, Switzerland, February 2022

- Reconnecting with the Landscape, the sound of running water, Hauterive #3, Switzerland, February 2023