Ben Responds to our Readers Questions

Ben Horne

I am a San Diego based large format landscape photographer. I spend several weeks each year photographing Death Valley National Park, Zion National Park, and other surrounding areas. Since 2010, I have documented my solo landscape photography adventures on my youtube channel — which now has over 26,000 subscribers. My video journal tells the story of each trip, and each photo. It can be challenging at times, especially when backpacking with an 8x10 camera, but the limitation and structure of working with this format helps me to be patient, and to wait for ideal conditions. YouTube

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

This issue we have a long awaited interview with Ben Horne, the YouTube'ing large format photographer from the US. We caught up with Ben just after his latest Zion trip.

Tim Parkin (TP): Hi Ben and welcome. We have a bunch of questions in from our subscribers for you. So shall I start going through those? There’s some about large format, some about photography, the photographic world, and general ones about your adventures.

The first one is from Roger Voller “I was wondering how does Ben keep his motivation up. All creatives have dips and I was wondering how Ben keeps his motivation so consistently high"

Ben Horne (BH): I think a lot has to do with the fact that my trips are all planned well in advance, and I have a lot of time to look forward to each trip. I typically go on three trips a year, so that allows several months of anticipation. I don’t do much photography here in San Diego because I really need to have a different mindset. I need to be away from everything for about a week so I can concentrate on what I am doing.

A lot of it has to do with the anticipation and excitement that builds up when I prepare for a trip, but it’s a different story once I get in the field. Every time I go on a trip, I forget how much work it is once I actually get out there. I’ll think I know what I’m in for, and I have very ambitious plans, but once I get there, I forget how far I have to hike and how much weight I have to carry. It gets real very quickly. On the first couple days of a trip, I usually have to force myself to record video, and to find the subjects. Once I get over that hump on day three to six, that’s when I’m on a roll. I’ll find a subject that inspires a shot, which leads to something else, and then something else. That’s why my trips are usually about a week or so at most because after that I’m physically worn out. After about a week, I don’t care how good something is, I’m just ready to go home and look at the photos I’ve already taken.

TP: This was one of the questions from Matt Smith:

“Obviously exhaustion affects problem solving both physically and creatively, how does he work with or combat that?”

BH: For me, each trip is kind of the same in this regard. The trip will be off to a great start and I’ll be productive, but at some point, I get tried — It is as though a switch has been flipped. The moment that switch is flipped, I forget about all those ambitious plans that I wanted to do, and I just want to head home. As an example, I recently returned from my annual fall trip to Zion. There were a few subjects that I wanted to shoot at the end of the trip, but once I got to that point when my legs were worn out and didn’t want to wander around anymore, I completely forgot about those subjects until I got home! I don’t think there is really a great way to combat it, but it definitely gives me a reason for a return trip.

TP: Presumably you are not sleeping particularly well when you’re out?

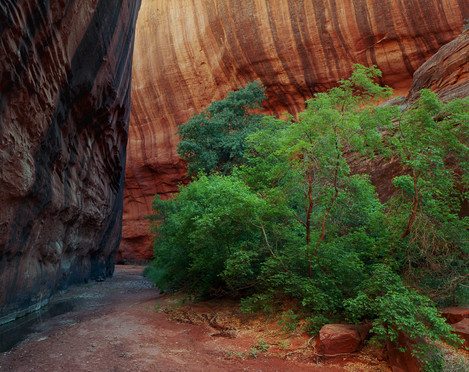

BH: I actually get some of my best sleep out in the field. Imagine camping in a canyon near a flowing stream with the sound of the wind rustling through cottonwood leaves singing you to sleep. I end up going to bed very early on my trips, though. I don’t have anything else to do once it gets dark. I’ll eat dinner and maybe load some film. I get good sleep but it’s not enough to overcome how much work it is each day and it builds up at a certain point.

TP: You’ve said before that you need that drive in to get you in the mood. However, have you not been tempted to find things locally to be able to adapt to weather conditions or to learn an area? (abbreviated question from Roger Voller)

BH: I have tried that a bit, but I haven’t been successful at it. The short trips, whether it’s just going out taking pictures of a nice sunset along the coast, or perhaps going out to a local desert, make me feel rushed. I never really get into that rhythm of shooting when I only have a day or two to shoot. I don’t have the time to fully scout an area, look for subjects, and come up with a plan. I need about a week in the field to be most productive.

TP: Is that to do with the amount of time or is it to do with the fact that the places you go to are twelve hours away, you got a real attachment to, as they are so beautiful you engage when you go there?

BH: It’s a combination of that. I think a change of scenery is important because it allows me to think a bit differently, but the bigger factor is distance. Death Valley is a five hour drive from my house and Zion is an eight hour drive from my house. If I’m in Zion and things aren’t going too well, I look at my watch and say “if I were to leave right now, I would get home at 2am so that’s not an option. I’m staying here another night”. Sometimes by the next morning, things are much nicer. That usually ends up being a good thing. If it’s an hour to drive home, I’ll just drive home and that’s it.

TP: It sounds like you’re like me, you use tricks to stop yourself from being lazy!

BH: Oh yes! For sure. I’m definitely one to do stuff like that from time to time. It’s like when you’re hiking on a trail and you want to see what’s around that next corner, then the next corner, then the next corner.

TP: The next question is from Olivier Du Tré:

“I would love to hear what Ben thinks his greatest weakness and greatest strength is when it comes to his photographic work.”

BH: I think that it’s actually the same thing, which is interesting. My greatest strength is also my greatest weakness. That’s the fact that I’m very stubborn. For example, I have a tendency to go back to the same locations again and again and again. I don’t branch out to new locations as much as I probably should. In some ways that can be seen as a weakness because I’m sticking with what’s familiar. Likewise, I have a limited scope as far as what I shoot. I might be in an area that has some really beautiful scenery, but I focus on the same type of subjects over and over again. Sometimes that feels like being in a bit of a creative rut, but at the same time, it’s something that has worked well for me over the years.

One of the strengths of being stubborn is that I get to know the locations incredibly well. It allows me to recognize when things are unique and special — that’s one thing I really do enjoy about that stubbornness. Also, by shooting the same locations over and over, and working with the same sort of subjects over and over again, I think it develops a sense of personal style and a level of consistency which is good to have.

In the category of strengths, being stubborn allows me to ignore the pressure of social media. People seem to post stuff just to get the likes and attention. Essentially they are posting things that other people might like. Whereas I’m the stubborn guy sitting back saying, “I just want to post what I like. I want to shoot the things I want to shoot”, so I end up shooting for myself, which is great.

TP: That brings up another question I was going to ask about social media - do you think in balance it’s a good thing or bad thing for photographers?

BH: It’s a classic double edged sword. It’s great to have the sort of connections that you can achieve through social media. Over the years, I’ve met quite a few photographers. If it wasn’t for social media, I wouldn’t know any of them! In that sense, it’s a positive thing. It’s a good thing to put your work out there, but it’s also a trap that people can fall into. A desire to get the likes and attention can change people's motivation. In the case of my YouTube channel, there are techniques people use to gain a much greater audience. It is a bit like following a formula. As I said earlier, I’m stubborn, I don’t want to do those things because it is not true to who I am. If I give in to that and follow the popular path, I wouldn’t enjoy it. I would be producing work for others rather than myself, and I don’t think I’d get much enjoyment out of that.

TP: No top tens or fake controversy then?

BH: No, not a lot of clickbait going on here!

TP: Another question. In the UK we have something called the Naismith’s Rule which gives you an idea of how it’ll take to do a walk. You tell it how long you’re going to go, how many ascents and descent you’re going to take and it gives you a time. I know I generally walk at about half Naismith as I’m unfit and get distracted too easily. When you go out and do one of your longer hikes when you’re camping, how do you work out the logistics of how long it’ll take to get there if you want to be in a place for a certain time.

Which also covers another question from Matt Smith: Which is how you cope with the weight of camera gear and trekking equipment if any techniques to minimise fatigue?

BH: It really depends on the type of trip I am on.The backpacking trips are the biggest challenge. I do a lot of research as far as what to expect. You get a good feel for distance and what terrain you’re going to cover. I know that I can generally cover about five to six miles over decently rugged terrain with my backpack. I really don’t venture extremely far, and I’m not doing any through hikes or anything like that where I’m covering tons of ground. It’s mostly, getting from A to B, set up camp there, stay there for a few days, and then get back out of there. Over the years I think my legs have developed in a good way that I have become a human mule! That’s good when lugging that stuff around but a lot of it is knowing your limits as far as how much water you need, how much food you need and what’s realistic as far as what you can achieve.

TP: That pack of yours with everything in it, what’s the weight? Approximately 60lbs?

BH: Yes that’s about right, On my last backpacking trip, I was carrying about 60lbs. That is with two or three lenses, four film holders and then all the survival stuff I need as well. I would love to get that down and I’m looking forward to when the Intrepid 8x10 camera comes out. The Ebony camera I carry is about 12lbs, and the Intrepid is going to be half the weight. That will be a noticeable drop in weight.

If I’m shooting from my truck and I’m not backpacking in, I’ll carry about 50-55lbs. That’s with more lenses and film holders, and that’s the normal weight that I am accustomed to carrying.

I will say that the first backpacking trip I went on, I carried way too much weight, roughly 80lbs. It was do-able, but it was painful and I’ve trimmed things down a fair amount since then. One of the things I’ve learnt is that the most precarious time is when you put the pack on, and take it off. You don’t want to twist your back in a weird way, so I have to be careful about how I do that.

TP: Sliding it down your body rather than throwing it on on the floor?

BH: Yes, that’s the one

TP: Another question from Matt Smith:

“How do you going about managing risk especially in remote locations?”

BH: The biggest threats to the areas I visit is dehydration and jumping. One of the things I’ve heard the rangers say in the past is that the number one reason people have a mechanical injury is that they are jumping from one thing to another. So if you simply don’t jump, you’re going to be much better off. If you stay hydrated, you’re going to do well.

As far as being away from contact, I do have a satellite messenger, so I can send messages back home to my wife. If something were to happen, I can send a distress signal. That sort of connection is great from a psychological standpoint. It isn’t a two way communication but I know at least I’m sending a message back home. If I were to run into someone else that has an injury of some sort, I can get them help as well. Anyhow, jumping and dehydration are the big things to avoid.

TP: So if you carry enough water you can’t jump, is that the logic?

BH: That’s really good way of saying it!! I didn’t think of that.

TP: Is that a satellite device a Spot one and what do you think about them if so?

BH: Yes it is. It’s pretty easy to use. A friend of mine recently showed me a Garmin that he used on a very rugged backpacking trip. It has two way communication, which is cool, though it’s best used with a smartphone to make the user interface even better. I don’t typically carry a smartphone with me in the field so that’s out.

TP: In terms of the large format camera - we’ve had a question: 5x4, 10x8 or 16x20?

BH: Of course I have to say this backwards, 4x5! I started with a 4x5 and I love the process of working with it but I quickly realised that I wanted to go to 8x10. There’s something about seeing that large ground glass which is great, and the camera slows me down even more. It has influenced the subject matter that I shoot, and I focus a lot of my attention on intimate landscapes, which the 8x10 does incredibly well. The 4x5 was awesome to work with and I was was very fast with it, but the 8x10 limits me more which I’ve grown to enjoy. I’ve no desire for the 16x20! That’s a huge camera. The 8x10 pushes the limits of where I can take it sometimes, so I don’t think I’ll ever shoot 16x20.

TP: In terms of that, if you’re looking for your pictures, you obviously can’t hand hold a 10x8 camera and look at the ground glass to try and find something. How do you visualise when you’re finding pictures.

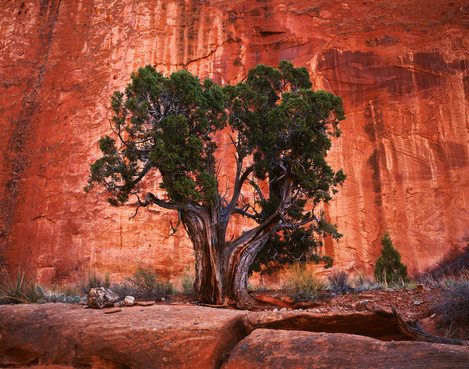

BH: I end up using my normal lens a lot. If I see something that looks interesting, chances are I can shoot it with the normal lens. In that sense, shooting 8x10 has shaped the style of my photography. With the normal lens, compositions tend to be very calm, and I think that comes through in the final photo. When I was in Zion recently, one of my favourite photos was taken with a wide angle lens using a vertical composition. It was interesting because even though I was standing right in front of the scene, I’m so used to seeing compositions fit for a normal lens, that I almost walked right past the scene. I was drawn to a rock in the foreground with lichen on it, surrounded by some grasses. Only later did I look up a little higher and see another rock with this beautiful tree in the background and this wonderful visual path that the rocks and tree form. I didn’t even notice it when I was standing there. It was only when I made myself look at all the various elements that I realized its potential as a wide angle shot.

That shows how much working with an 8x10 camera and a normal lens has shaped my own vision. I know some people swear by the viewfinder app that you can get on your phone so you can sit there and look at a scene with your phone. I’ve been reliant mostly on the fact that I see things through a normal lens, but then sometimes I have to force myself to see a wide angle composition. I’ve been really enjoying using my 600mm lens recently to isolate things a little bit. That’s another focal length I can visualise just by looking at the scene.

TP: I did have a side question as well! Do you know anyone who’s got a Fuji 600C going? I’ve been trying to get one for the past ten years. The only time I was successful, someone else wanted it so I let them have it.

BH: Those are really hard to get. I was really lucky to find one. Daniel Duarte, a very talented photographer friend of mine, emailed me a while back and said a friend of his had one for sale. I had already purchased a Nikon T 600mm lens, so I told him I had found a solution. However, after going on a trip with that monster of a lens, and wishing I had the smaller Fuji instead, I messaged him back and asked if that lens was still available. Thankfully it was! I get the feeling that I got the last one on Earth.

TP: Do you think shooting large format helps you spend more time engaging and looking at the landscape?

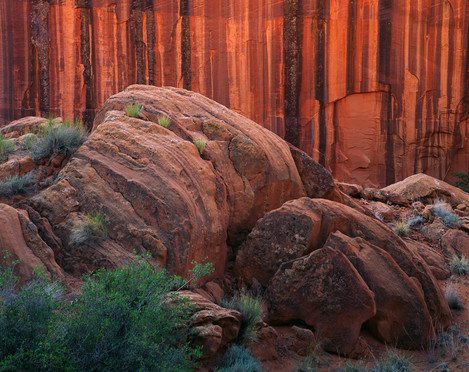

BH: Definitely, I think it shapes the way I look at the landscape. Just as I said earlier, most of the time I use a normal lens, which draws me toward intimate landscape photos and other scenes that I otherwise might not even have noticed. It’s incredibly limiting in a very good way. A place like Zion has so much beauty in every direction, but using the 8x10 forces me to shoot certain subjects. I find that it’s a useful, and interesting way of making me see things differently.

TP: We’ve been writing a series on large format, and one of the things people generally have a problem with is exposing Velvia 50. Exposing neg is not a problem as it has such latitude, but Velvia 50 can be a real challenge. Everybody I speak to has little intricacies that they use when they are exposing it. So what’s your take on how to do it?

BH: It’s definitely a tricky thing to do. It requires a lot of precision but I’ve gotten pretty good at it through the years. Typical I just put the important highlights between 1.5 stops above neutral and at most 2 stops above neutral.

TP: Pentax or Sekonic light meter?

BH: I have a Sekonic 558 and I’m probably transitioning to 758 pretty soon as I lost one of the dials on my meter when I was in Zion. It still works despite that! I put the highlights between +1.5 and 1.8, somewhere in that range. For the shadows, -2 or so is the darkest I would go to hold detail. I rate it at 50 speed and if anything I try and exposure as bright as I can without overexposing the highlights — knowing that I can darken that down afterwards.

TP: Graduated filters?

BH: Yes, for those few times I actually have any sky in the photos! I use Lee grads

TP: Do you use graduated filters when you’re photographing intimate details?

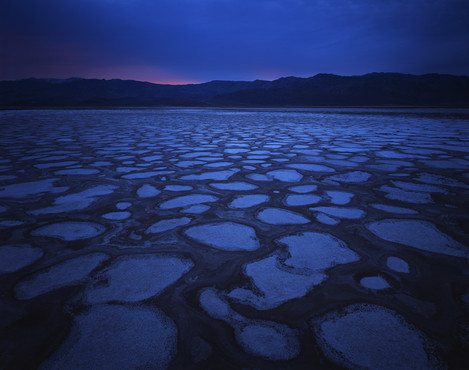

BH: No, never for that. It’s usually a very controlled situation. Just if I’m shooting big skies and stuff like that, more like a Death Valley thing perhaps.

TP: Obviously you shoot colour negative and transparency film, and colour negative is quite a subjective medium in the fact that once you’ve got it you can choose a white balance, contrast, brightness etc. and that means that you are going to do some post-processing of some sort or you allow somebody else to do that. Do you work on your Velvia scans the same way?

BH: When the film is scanned, it’s a case by case basis, but I usually try to make sure that the shadows have plenty of detail and the highlights have plenty of detail. As a result, the scan is usually relatively flat. If I’m having colour negative film drum scanned, I usually provide the scan operator with a rough idea of what it should look like. I usually give them a file that has a bit of lower contrast, lower saturation etc, so they have all the information. The same thing is true for the Velvia as well. I recently sent off a dune photo to get drum scanned and there are some dark shadows in there. I put in the request to get as much detail as they can in those dark areas, as I know it’s there. I know that I can work with it afterwards on the computer.

TP: You do some post processing, do you do that work on both transparencies and negatives?

BH: It’s fairly straightforward. I typically work with a curves adjustment layer since the original scans are often very flat. Sometimes I also need to correct a strange colour cast with the film. Velvia likes to go very really blue in the shadows which sometimes can be nice but sometimes it can be a distraction. I typically use Velvia in low contrast scenes where the colours are actually fairly normal. If you use it in high contrast, it goes kind of cartoonish. That’s something I definitely have to reduce in photoshop. I want to keep things a bit more realistic. The natural colour likely has enough merit, so I don’t want the final photo to go overboard with colour.

TP: Given that transparency film has a punchy colour in contrast and colour neg generally has a flatter look if you look at the old contemporary or new topographic photographers. If you scan them as default they would look obviously from different film stocks. Do you post process to try and bring them towards each other, so you get a slightly flatter look out of your Velvia and punchier look out of your neg?

BH: I think that’s true, I try and meet in the middle with it. When you consider the fact that I usually use Velvia and other slide films in relatively low contrast situations, the saturation and contrast added by the film simply bring it up to a point where it’s a bit more saturated than reality but it’s not overboard. Likewise, if I’m using colour negative film, I’m using it for high contrast scene since it deals really nicely with those bright highlights and deep shadows. When I’m working with that, it’s a matter of trying to give it that look of Velvia in the low contrast situations. I can look at photos and I can tell if they were shot on Velvia or Ektar. There’s definitely a different look to Ektar but I try to keep it somewhat cohesive and either film can go wild at times. I feel I have to try and control either one to get it somewhat back to reality.

TP: Do you use Portra?

BH: I used to. I used it for a while and I probably haven’t since 2011 or so. It did well but at the same time, you can make the film into whatever you want it to be when you scan it. I had a hard time seeing the difference between Ektar and Portra. Unlike slide film, it all ended up being the same. By working with just Ektar, I can simplify my film freezer. I’m sure it would be a much different situation if I was shooting portraits, but for landscapes, I think they are quite similar.

TP: Next question from Matt Lethbridge:

“Did you realise just how inspiring your video journals would turn out to be when he started? His adventures turned my thinking towards LF photography and along with Tim showing me how accessible it was and just how good a large piece of film looked on a lightbox that totally convinced me that this was the way I wanted to go and I'm sure I'm not the only one to start my journey after watching his............ “

BH: It’s still weird to think what’s possible these days with the internet and social media. From my standpoint, I spend a few hours a week producing these videos. To my knowledge no-one really watches them. So it’s kinda cool when you see that they do have an impact. Often times when I’m in the field, I run into people who have followed my work. It’s great to meet people who are like-minded and really enjoy landscape photography.

It is interesting how that works out, the power of it all. When I originally set out to do this, it really wasn’t for that purpose. The word “vlog” has since become a mainstream thing but I never really use that word. I have always called them video journals. To me, a vlog is a something designed for entertainment value versus a video journal which is more like a hand-written journal in video form. It’s more personal like that. I’m not producing the videos for entertainment, similar to how a handwritten journal isn’t produced for entertainment. In some ways, I make the videos for myself so I can look back at them and relive the decision making process and understand why I did what I did. The same thing applies to my film reveal videos where I record my thoughts and reaction to seeing my film for the first time. I am fascinated by how our own perception changes with time. I might love or hate a photo at first glance, but then give it days, weeks, months, years and that perception will change over time. That is one of the reasons why I started filming the video journals — to remember the experience of being out in the field.

There’s another benefit of that as well. If I’m out in the field on a backpacking trip and I haven’t seen anyone for a few days, talking to the camera is actually kind of a good thing. It helps me talk through the process of why am I'm here, what am I doing, and come up with a plan. There have been some cases where talking to the camera helped me make some important decisions.

It’s an interesting world we live in where all this is even a thing.

TP: I have been saying to some of my nieces that they’ve got to realise the jobs they end up doing may well not exist at this point in time.

BH: For sure. None of this stuff really existed when I started shooting the video journals and going on these trips. It’s weird to think that you can even earn some degree of a living by doing this.

TP: Next question from Olivier Du Tré and I’m not sure what context this is in:

“And what scares you the most about the photo world.”

BH: I’d say it’s two part - the first is the availability of film. I depend heavily on Velvia 50, and Fuji seems to enjoy killing off the film stocks we like the most. If it was discontinued, I could still shoot. There’s Kodak Ektar, there’s Fuji Provia, there are other options out there — but when there’s one particular film that you depend on to make life easier as a photographer, and it gives you the look and feel you’re going for, I’m really tempted to buy a tonne of it to add to my stockpile.

TP: Last time they tried to cancel it, a hell of a lot of people did that. They took out loans to get the film and then when they finally brought it back they wondered why people didn’t buy more of it immediately!

BH: Exactly, there’s got to be better ways of doing that to keep it around. I just want to give Fuji my money for their great film. That’s one of my fears. What’s going to happen in five to ten years down the road?

The second thing that scares me most about the photo world is finding a way to make a living with landscape photography. This has always been at the back of my mind, but it has been progressively getting better with each year. I’m not at the point where I can do this full time but maybe in another year or two that might be a possibility. That’s always in the back of my mind. Things are moving in a good direction, so that’s a good thing.

TP: In terms of your photography creatively or artistically, for want of a better word, what are your goals?

BH: That’s a tough one. I don’t have any specific goals other than trying to find a way to keep doing what I love. That’s what it comes down to. I’m not really interested in leading workshops or doing some of the other things that people have traditionally done to earn an income as a landscape photographer. My goal is to find a way to earn an income by doing what I truly love. To me, that is the definition of a perfect job.

I think it’s a matter of finding balance in life. There are bills to pay and other obligations but I’m not really interested in having a huge income. That doesn’t motivate me. Just so long as I can spend time doing what I enjoy. When the economy wasn’t doing so well back in 2008-09, I voluntarily furloughed myself from work, and said: “don’t pay me, I’m going off on a two week shooting trip”. That’s how I got started doing all of this and I’ve been doing that ever since.

TP: The recession was good for something then, always look at the positives!

BH: Yeah, it forced change. It forced people to look at things differently. In my case, it was a great time to get into large format landscape photography.

TP: That’s fantastic, thank you so much for that and for your time.

BH: really enjoyed chatting

If you haven’t watched any of Ben’s videos you can catch his Youtube channel or his website.