Part 4 of a Series on Large Format Photography

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Richard Childs

Richard trained as an Orchestral Percussionist in the 1980's but his true love has always been the outdoors and particularly mountain environments. Throwing in his drumsticks to become a full-time photographer in 2004 he continues to work with a large format camera alongside digital equipment and exhibits his work in solo and group exhibitions as well as at his own gallery in the Ironbridge Gorge. Links to Website and Facebook

When people first try out large format photography and they come to the choice of lens for their first kit, they typically make a few common mistakes. Hopefully, this article will address some of these and also expand on what makes the large format lens such a unique object.

Lens Equivalents

The first problem most people encounter is choosing a focal length. Received wisdom has it that the conversion factor from 35mm to large format (5x4) is 3x. Sadly this received wisdom causes no end of people to buy lenses that are far too wide for day to day use and is a real barrier in certain conditions. The actual answer is a little more complicated because the aspect ratio of the two formats are different. To this end, I’m going to give two sets of tables and which table to use depends on how you plan on photographing with large format camera.

If You Take Panoramic Pictures...

If you typically use your 35mm camera to take horizontally oriented photographs or crop to create panoramic photographs then the difference between the two formats is the ratio of the film/sensor sizes longest edges. 35mm film/sensor is 36mm across the long edge and 5x4 film is 120mm across the long edge. Hence the conversion ratio is 120/36 = 3.333x

Here’s the conversion table for common LF focal lengths

| 5x4 Focal Length | 35mm Focal Length |

|---|---|

| 72mm | 22mm |

| 90mm | 27mm |

| 110mm | 33mm |

| 150mm | 45mm |

| 180mm | 54mm |

| 210mm | 63mm |

| 240mm | 72mm |

| 300mm | 90mm |

| 360mm | 108mm |

If You Usually Crop Your 35mm Photos to 5x4 or Square...

If you commonly crop your 35mm images to 5x4 or even square then the difference between the two formats is dictated by the short edges of the film/sensor. 35mm film/sensor is 24mm and 5x4 film is 96mm. This gives a ratio of 96/24 = 4x

Here’s the conversion table

| 5x4 Focal Length | 35mm Focal Length |

|---|---|

| 72mm | 18mm |

| 90mm | 23mm |

| 110mm | 28mm |

| 150mm | 38mm |

| 180mm | 45mm |

| 210mm | 53mm |

| 240mm | 60mm |

| 300mm | 75mm |

| 360mm | 90mm |

If we had used the 3x conversion and were typically using a 24-70 zoom lens, our LF equivalent lens range would be from 72mm to 210mm. A 72mm lens is actually a bit of a monster and quite hard to see in the corners in darker conditions and if you typically crop to 5x4 or square then this is actually equivalent to an 18mm lens, not 24mm. Quite a difference!

Given the ‘I crop to 5x4 ratio’ condition, a 24-70 lens is actually from 100mm to 300mm. If you talk to a lot of large format photographers you’ll find that there is a very common lens ‘set’ of 90,150,210 plus sometimes a 300mm and this matches quite closely with the 24-70 zoom lens.

Which Focal Lengths Should I Buy?

Now you’ve got an idea of what the equivalents are between LF and 35mm focal lengths, you can look at choosing a range of lenses. It’s often hard to work out what focal lengths to buy if you’ve mostly used zoom lenses in the past, but people who work primarily with prime lenses tend to stick the the same focal lengths. It’s very common for someone to carry the 24, 35, 50 and 80mm lenses and these are close to the 90, 150, 210 and 300 common focal lengths mentioned above. Some people do prefer to ‘shift’ this range a little by starting off with some a little less wide and so you could have a 135, 180, 240, 300 (the 135 being a very nice 33mm equivalent).

[ My own choice was based around a bit of a classic lens at 110mm (28mm equivalent) and then I worked up from their with a 150, 240, 300 ]

It’s a rare photographer these days that doesn’t have a long lens and an ultra wide in their collection and it’s very tempting to try to get an equivalent lens for their LF collection. Unfortunately, lenses start to become more demanding once you get beyond a certain range and for LF this range is anything wider than 90mm and anything longer than about 300-400mm. Hence if you wanted something to replace your 70-200mm you’d be looking at a 300 to 720mm and you’d need to buy telephoto lenses and also buy a camera that allows you to extend the camera bed a lot further than normal (most cameras that can focus a 720mm at infinity are quite bulky).

At the wide end, people may have a 16-35mm lens and if you want to shoot panoramas at the wide end of this you would need a 54mm lens. The nearest equivalent would either be the 47mm or 58mm Schneider Super Angulon which can be a nightmare to use because in most cases you won’t be able to see all of the image at once (you have to move your head around to see the diverging light rays, even with a good fresnel) and the image can be so dark that it’s difficult to focus, especially in twilight.

For now, this article will restrict itself to the ‘normal’ lens range from 90mm to 300mm and we’ll cover the more extreme focal lengths in the next instalment.

A Look at What Makes a Large Format Lens

If we step back a little and compare our typical 35mm lens with a typical large format lens, we quickly see an obvious difference. Firstly, nearly all modern (post 1950s) large format lenses include a shutter unlike 35mm cameras which have the shutter built into the camera. The most common shutter you will encounter is a Copal which comes in three different sizes, a 0, 1 and 3 (the Copal 2 was never made but there was a very old Compur 2 for which no modern equivalent is available, hence the missing 2!). The size used on a particular lens is usually dependent on focal length and maximum aperture. Long fast lenses tend to use a larger shutter and short, slow lenses tend to use a smaller shutter (if a lens covers a big image circle it might also use a larger shutter). i.e. It all depends on how the light rays pass through the middle of the lens.

One of the benefits of a shutter built into the lens (or a ‘leaf’ shutter) is that they generate almost no vibration in use, unlike the mirror and focal plane shutter on smaller format cameras (if you’ve ever heard and felt a Pentax 67 shutter firing you can image what sort of noise you’d get from a larger format focal plane shutter). The downside of the leaf shutter is that you tend to be limited in shutter speed, for instance the Copal 3 can only manage 1/125 of a second. (although an added bonus is that you can flash sync at 1/500th of a second on a Copal 0 shutter! Not so much use in the landscape though).

The shutter also has the aperture built in and if you want a nice round aperture, most older Copal or Compur shutters have more shutter blades (modern Copal have 5,7 or 7 for 0,1 or 2 shutter size whereas older Compur or Compound shutters can have 9 or more blades but can be unreliable).

Most shutters also have a lever to open the shutter to allow you to view and focus the image on the ground glass (on older shutters you might need a locking cable release to use on the B setting). Remember to close this before you pull your dark slide (you will make this mistake at some point! A good checklist is useful when you’re beginning LF).

The front and rear element set of your lens screw into the front and back of your shutter. The screw threads are brass and can be easily damaged by impact or cross threading (try turning the element in reverse until it ‘clicks’ into the thread position and then thread forward).

Finally, the lens will have a mounting ring at the back which allows you to mount it to a lens board. Some lens boards have a hole that matches a little grub screw in the back of the lens. This is rare and if you buy a new lens, don’t forget to remove the grub screw as you lens won’t mount properly in a lens board that has no hole.

The way the lens is oriented is a personal choice. I try to go for consistency in the position of the shutter open/close lever so that it’s at the top. Other people like to have the shutter cable attachment pointing up or the aperture control lever and shutter speed control easily accessible.

The cable release attaches to the shutter via a small mounted metal block. This is quite strongly attached to the shutter frame but if it does break it’s an expensive fix!

Lens Design from 35mm to Large Format

There are a quite a few quality bonuses of working with large format and one of the biggest for me is that nearly all LF lenses are way better than your average 35mm lens. This is due to a range of things but the key feature is that as the film/sensor surface gets bigger (by 4x when moving from 35mm to 4x5) the same manufacturing standards deliver 4x the quality of lens. In actual fact most landscape photographs are taken at f/22 to f/32 and hence are diffraction limited and not lens limited anyway.

You can add to this advantage the fact that large format lenses also tend to be a lot ‘simpler’. Older large format lenses used a ‘Tessar’ design which just had four lens elements in three groups. The ‘Plasmat’, which took over in the 50’s/60’s, had six lens elements in four groups. The plasmat in particular is a very efficient lens design and is sometimes used for macro lenses in 35mm cameras.

The reason this great lens design wasn’t used for other lenses on 35mm cameras is because the mirror box got in the way for wider lenses and in addtion it could only be designed with an f/5.6 aperture. Of course, for large format work f/5.6 has the same depth of field as an f/1.4 lens for a 35mm camera so is more than enough for creative work but most 35mm photographers demand something a bit faster.

Here’s a diagram showing some high end lens equivalents for 35mm, medium format and large format.

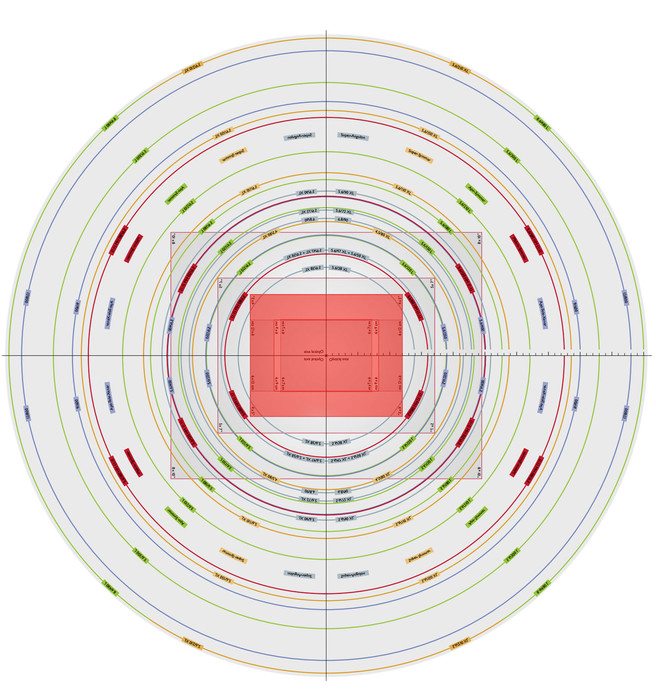

The final difference between large format lens design and 35mm lens design is that large format cameras make a great deal of use of lens movements and hence the lenses need to have a bigger image circle to allow these movements. The image circle is the size of the circle of light that the lens projects. The diagram below from Scheider shows the size of the lens’s image circles in comparison with the 5x4 film area. As you can see, many lenses allow you to shift enough to take two 5x4 photographs side by side (the equivalent to covering 10x8) and some allow you even more movement (probably more than your camera will allow).

In reality, the most image circle you will ever use is half a frame (if you want to keep the horizon in the picture and still correct verticals or you want a full side to side panorama) and typically for landscape photography, you can get away with about a quarter of a frame extra. You need 154mm image circle to cover 5x4, 231mm for a quarter of a frame extra and 308mm for a whole frame extra (i.e. it would cover 10x8). Here's a diagram of typical image circles for Schneider lenses from their PDF catalogue. The 5x4 area is shaded in red and you can see that some lenses have massive image circles but these have been designed for use on giant cameras that take up to 20"x24" film!

Choosing Your Large Format Lenses

The choice of a large format lens can be a difficult one for the beginner. Lens review websites don’t exist for these lenses and wading through old forums to separate truth from fiction is time-consuming and unreliable. The good news is that large format lenses are very rarely bad enough to be able to see even in large prints. If you buy a lens mounted in a Copal shutter, it is almost certainly a modern lens and will give results that far exceed those from any but the most expensive 35mm system. If you limit yourself to certain families of lenses then you will far exceed any 35mm lens and will rarely pay more than £300.

Given that all of these lenses are so good, why do people pay more money for some lenses then? Well, the main reason is to get more ‘image circle’ to allow capacity for more shift. For instance, the Rodenstock Sironar-N often goes for £150-£300 on ebay whereas the Sironar-S can be seen changing hands for £600-£1200. All this extra money for a meagre 15mm extra image circle (from 215 to 230mm) and some very minor improvements in flare control and sharpness in the corners! If you’re making extreme enlargements and using full movements then the S might make sense but that’s a huge amount to pay for this. Read my personal comments section at the bottom of this article to give you some perspective on this.

Just as in most things there are some ‘standard’ manufacturers and product lines. Large format is no different and the big manufacturers (Fuji, Nikon, Schneider and Rodenstock) all created stunning lenses in the latter half of the 20th Century. Here’s the product codes to look out for. You won’t go far wrong with any of these.

65mm to 90mm

Fuji SW & SWD

Nikkor SW

Schneider Super Angulon (and XL)

Rodenstock Grandagon N

100mm to 450mm

Fuji CM-W, A, C

Nikkor W, SW, M

Schneider APO-Symmar

Rodenstock Sironar N and S

I could make a longer list including some more lenses but these are the most common lenses but these are probably the most common lenses in collections I have seen and most likely to still be in good condition (e.g. I’m missing out Ektars, Doctor Optics, APO-Germinars, APO-Ronars etc but I figure as you get more into large format photography and feel a need for different lenses you’ll be talking to more people, browsing forums more often, etc and will have identified a special ‘need’ perhaps).

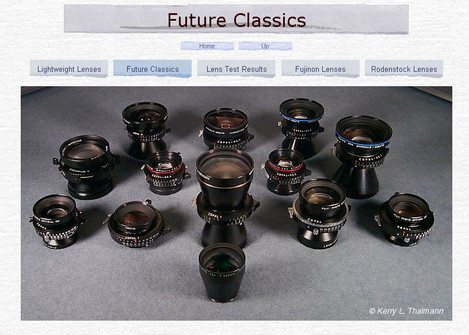

The Curse of Kerry Thalmann’s “Future Classics”

The problem with Kerry’s fantastic article “Future Classics” is that it probably single-handedly doubled the price of every lens listed (see the aforementioned Sironar S/N comparison). These lenses are all very, very good but do they deserve the price premium they have inevitably gained? I’m not so sure… Would I sell mine? No… :-) The website is worth a look and if you happen to get any of the lenses included at a reasonable price, they’re sure to be a good investment.

Will Your Lens Fit Your Camera?

Now unlike SLR systems where every lens will fit every camera (given a particular lens mount like Nikon or Canon) large format cameras have certain constraints that can limit what lenses you might want to mount.

The first constraint is your bellows and the mechanical structure of your camera. If your bellows will only extend to a certain length then you can only fit a certain focal length of lens (and you might not be able to achieve infinity focus on some lenses). e.g. A 450mm normal lens will need 450mm of bellows extension to focus at infinity. Telephoto lens in large format don’t refer to just a long focal length, they refer to the fact that a lens can be focussed at infinity at a shorter bellows length. E.g. The 500mm Nikkor Telephoto lens can be focussed at infinity with 350mm of bellows. Quite useful!! If you want to know how much bellows extension you need then you should look up the ‘flange focal distance’.

At the other end, if your bellows doesn’t compress enough then you won’t be able to achieve infinity focus (if your bellows length is greater than the flange focal length then you’re focussing closer than infinity). Most cameras manage to focus a 90mm lens but some struggle with wider lenses. It’s worth checking whether your camera can manage before investing.

There are a couple of ‘tricks’ you can use to mitigate this problem. Some lens boards are either recessed or have extensions at the front called ‘top hat lenboards’. These can cause a few issues as the nodal point of the lens moves around when you tilt the camera - nothing that can’t be handled if you need to solve a problem.

If you want to find out more about large format lenses, I spent a while compiling information from various sources online and put them into a Google spreadsheet.

How Many Lenses?

There are no rules! You can work with a closely spaced set of lenses 72, 90, 120, 150, 180,210, 240, 300, 360, 500 & 720 or you can manage with a classic spread of 90, 150 and 210. In fact many photographers work with just a single lens, quite often a 120mm to 135mm gives a very natural field of view and a consistency to your work that can be very effective (look at Jem Southam’s work).

If you have any questions, please add a comment at the bottom of the article and we’ll try to get answer. In the meantime, don’t worry too much! You can’t really go too far wrong and if you buy the wrong thing, as long as you didn’t overpay you should get your money back on resale!

Tim Parkin

When I started large format photography, I was fortunate to exchange a few skills in website development for a few lenses. I remember giving a range of lenses, chosen from the aforementioned “Future Classics” website to my colleague and saying “Get me one or two from this list if you’re happy with the website”. He must have been very happy as he got me everything on the list, all brand new. So here I was with an 80mm and 110mm Schneider Super Symmar XL, a 150mm Rodenstock Sironar S and a 240mm Fujinon A. I couldn’t have been happier with the range of lenses but I quickly found out that the 80mm was difficult to use. Even at f/4.5 wide open it was still darker than I thought it would be. I soon sold it and bought a Nikkor 360/500 instead.

I now owned the main lenses I would use for the next few years. Having not used any ‘cheaper’ lenses (or ones not on the Future Classic list) I had no idea whether what I had was amazing or not. However, a few experiences made me realise that if they were amazing, the differences are subtle.

The first was when I began my scanning business and was looking at many peoples large format photographs. The thing that stood out was that they were all very good. It was rare to see a 5x4 photograph that didn’t wow in terms of sharpness and detail and when I asked about one that was softer, it was usually taken at f/45 or even smaller.

The second was when I started taking photographs of military battalions and thought it would be best to have a duplicate camera and lens setup (belt and braces!). To this end I used my Chamonix camera and bought the cheapest 150mm Schneider APO Symmar I could find, a £45 beaten up sample from ebay. To my surprise, when I came to look at the drum scans of these two photographs, I couldn’t tell the difference! Now I’m sure at the extremes of movement and in certain conditions, there will be differences but in most cases they will be marginal.

Since then I have invested in, and inherited a few extra lenses. A Nikkor 300M (for my 10x8 camera but works really well on 5x4 as well as a Nikkor 200M and I also bought a 75mm Rodenstock Grandagon N which although it has an f/6.8 aperture is beautiful.

Like Richard Childs, I tend to use a different lens setup depending on what I am doing. If I’m doing some mountaineering, I might take a 90mm f/6.8 Angulon (a tiny lens I got for a Travelwide Kickstarter camera with not much coverage but sharp enough to make big prints), the Nikkor and a Nikkor 200 M. if I’m just walking around for a few miles, I might take a 110, 150, 240 and 300 lens (or include the 75mm or 360/500 if I know what I’m going to see). Finally, if I’m working next to the car I’ll take the lot (if it’s not too much hassle).

The main thing to know is that it’s more than possible to take fine pictures if you only go out with two or three lenses (or even one!).

- Singing Sands, Eigg – 110mm Schneider Super Symmar XL

- Barnluasgan, Knapdale – 150mm Rodenstock Sironar S

- Ballachulish – 240mm Fujinon A

- White Moss – Nikkor 360mm T-ED

Richard Childs

I didn’t really need to think about lenses when I first took up Large Format Photography. My first camera came bundled with one, a nice, chunky Schneider 90mm Super Angulon Classic. Once I had worked out that I needed a lens panel and had it attached to my RSW45 I was delighted. With hindsight, however, the 90mm was definitely the wrong ‘only’ lens to start out with as it offered very little flexibility and choice with subject matter. A 150mm lens would have been far better proving me the option to shoot both views and details in equal measure.

I still own my original 90mm lens which, even when I’d added to my stable on lenses, was my go-to lens for probably the first five or six years. These days it sees very little action as I opt for a more natural feel/look in my wider shots. I have never owned a 150mm but only because I bought a Rodenstock 135mm and then a Schneider 180mm both of which get me very close to the classic 150 view. There has always been much discussion around what is the best spread of lenses to own. Should you go 90, 150, 210, 300? Or 72, 110, 180, 240 etc. Should you have lots of lenses or maybe just one or two? The answer is, of course, whatever suits you and your photography and this can only be achieved through trial and error and as your photography evolves. I have carried as many as six lenses out on the hill but at the moment tend to go with just one ( and the security of a digital camera covering other options-earning my living from photography I do often have to return with something and Shropshire’s hills have proven to be particularly exposed to Westerly winds).

My typical spread included 72, 90, 135, 180 and 300mm lenses. A 210 or 240mm lens would have perfectly finished the range but never owning one has only had the effect of changing slightly what and how I photographed on a particular day.its absence didn’t mean any missed images because the lenses I did carry would define what I shot. This year I’ve been heading out with only one lens, a Rodenstock 120mm Sironar-N. A Schneider 110 would have been my first choice but at more than five times the price I couldn’t justify the expense. I’ve been enjoying both the discipline, and freedom, that this has brought to my photography not to mention the huge drop in the weight of my bag.

I no longer own the 72mm lens as I immediately found that I didn’t like the overstretched, super wide look. I kept it for about two years before selling it on having only used it a handful of times. It did however enable me to photograph the fissured shoreline in Norway where I simply couldn’t move myself and the camera any further back as we were right up against a four-foot high rock wall. My 90mm lens meant for too tight a foreground and the 72mm solved the problem but was one that I have only experienced a couple of times in nearly fifteen years. Little need then to carry this heavy lens along with special push fit filter holders. I no longer own my Fujinon 300T lens either which I do strongly regret as it would be perfect for some of the woodlands I have visited. However, in open countryside, I’m afraid I do reach for my digital camera with its 70-280mm range as this provides me with a far more stable platform in exposed locations.

I’m sure that Tim will be discussing some of the more technical points ( advantages/disadvantages) of certain types of lenses. Sharpness is not something I’ve ever really been obsessive about. I feel I’ve been quite fortunate in my career in that it hasn’t been a critical consideration in my workflow. That’s not to say that I don’t try my hardest to gain sharp focus when I’m making an image or that I would accept a poor performing lens. However, it has meant that I haven’t had to go looking for the most expensive glass. In my experience it’s only we photographers who press our noses right up to the glass when looking at a print. All of my lenses help me create a wonderful, natural looking sharpness that, combined with film produce prints that make me happy which is what matters.

Large Format Photography Articles

- Wyre Forest – Fujinon 300T

- Luskentyre – Schneider 90mm SA Classic f6.8

- Bentsfiord – Schneider 72mm SA XL

- Aluminium Factory – 135mm Rodenstock Sironar N