It has long been photography's cross to bear that of all the crafts and communication media it is the one whose image is most tainted by associations mechanical (as I suspect David Ward once wrote); that, and its apparent easy-ness. It seems that the vast majority of camera advances involve automation of one sort of another. Make photography easy and cheap enough and everyone can and will take pictures. And that is literally what has happened. George Eastman of Kodak fame who promised, “You press the button, we will do the rest”, would not have been surprised by this turn of events (although he might have been dismayed by the lack of print sales.) The emancipation of photography is, like reading and writing, a good and educational thing. But pressing a shutter button is only one small part of a process which is primarily about understanding and seeing light, and composition, and visual story-telling.

Yearly Archives: 2014

Timo Lieber

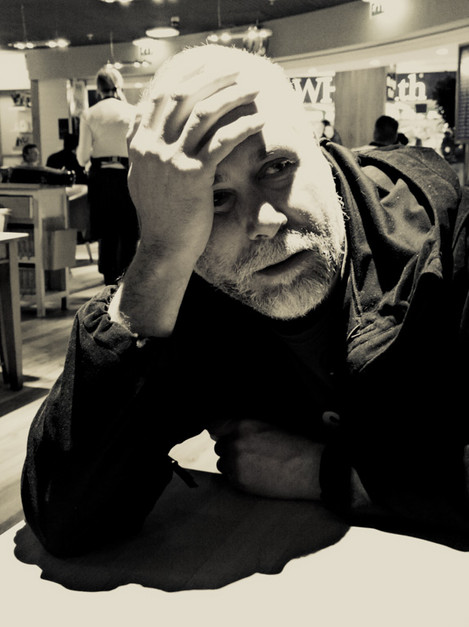

Welcome to our featured photographer section where in this issue we'll be talking to Timo Lieber, a German photographer living in London and who has recently been shortlisted at the Sony and Wildlife Photographer awards.

Can you tell us a little about your education, childhood passions, early exposure to photography and vocation?

My degree and day job are in finance and hold little relevance to photography. I did, however, enjoy helping my dad putting together films from family hikes, so picking up a camera felt very natural.

I bought my first DSLR a few years ago and things have progressed from there.

End Frame – Porch, Provincetown, 1977 by Joel Meyerowitz

When I was asked to contribute to ‘End Frame’ I readily accepted, thinking what could be easier than writing about a favourite photograph? Then I started to think about which photographer to pick, and exactly which image, and the problems suddenly seemed to multiply. Who do I consider my favourite photographers? How can I possibly pick a favourite image from so many? I can easily reel off the names of a good couple of dozen photographers whose imagery I particularly enjoy and who have had an influence on the evolution of my own photography. Taking away some people about whom much has already been written still left a pretty long shortlist. Who to pick….? The American photographer Joel Meyerowitz might seem a strange choice to write about in a magazine devoted to landscape photography - having made his name in the 60s and 70s shooting fast on the streets of his native New York.

Issue 74 PDF

You can download the PDF by following the link below. The PDF can be viewed using Adobe Acrobat or by using an application such as Goodreader for the iPad.

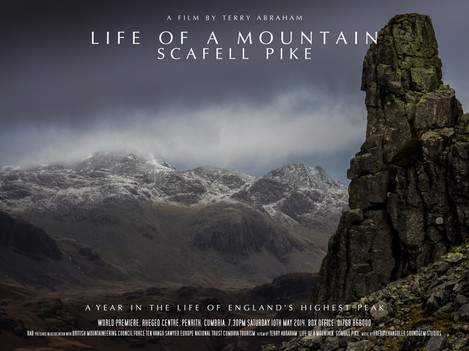

Terry Abraham Interview – Life of a Mountain

On Landscape have helped the Rheged to put on an exhibition of Lake District photographers and also a talk by David and Angie Unsworth and a workshop by Mark Littlejohn to coincide with the launch of Terry Abraham's movie "Life of a Mountain", a full feature about Scafell. We talked to Terry about his project and asked him how he the whole thing started.

Tim: We’ll start off asking you a bit about your background as a photographer film maker. What came first for you? I’m presuming it was the outdoors before filming and photography.

Terry: I’ve always had an interest in film and video. As a young man, I always daydreamed of producing my own films one day but such is life and it never really came to fruition but that interest was always there. I’ve always had a love and passion for the outdoors. A few years ago, I bought a cheap camcorder, started taking it out on my camps up the hills, built up quite a large following on the likes of You Tube and it’s really thanks to modern technology and the Internet that my career’s been born from there in terms of getting the interest. I won a couple of amateur film competitions. I started the video making side of my trips and capturing the hills but more seriously and then I got made redundant in a job I was doing in IT. At that point, I was moonlighting at weekends producing short videos of the Peak District for various tourism bodies and I thought, I’m going to go for it as a full time living. Invested in better and more professional equipment in terms of the craft of making videos and it was very hard, it was a struggle but I got through the first year. They always say the first year in business if you’re still going, you’re onto something. If you keep going after two years, you’re definitely onto something and also it’s going to grow and that’s exactly what happened. It’s all led to me producing this film about the Scafell, it’s a long held ambition of mine where I could produce something I wanted to see not somebody else wanted to see, like some clients I work with. The photography came out a year or two ago, I’ve only started taking the photography seriously. Some friends I speak to on Twitter are saying, “You’re taking some fantastic shots on video, why are you not taking photos?” and I’m going, “I don’t have a DSLR or anything like that,” so I’ve invested in a DSLR and now, about a quarter of my income comes from the photography. I don’t put the images out online on the likes of Alamy or anything like that. I’m quite fortunate in that I get approached by companies and then commissioned to do photos. Anything I put out online gets picked up my magazines and they get in touch and so on.

Tim: That’s where the money comes from, commissions, with the landscape photography.

Terry: Yeah, that’s something I learned. A lot of what I’ve just talked about has been a very steep learning curve for me. I’m not formally trained with anything like this at all. I’ve taught myself. I have to say I was considered a talented artist as a young man and I was an illustrator till my mid-twenties and I suppose I’ve got a natural eye for seeing a picture. In a roundabout way that’s what shows through the work I do, particularly with videos, it’s always about that composition, getting that picture. But whereas I could create something as an illustrator or change things or arguably some people do with Photoshopping images, with video it’s all about being in the right place at the right time. I can’t do anything with the image afterwards.

Tim: No, very difficult, not like what you can do with Photoshop, video hasn’t quite got to that stage yet, fortunately I would say. But you’re not from a mountainous area; Nottinghamshire is not exactly full of the peaks.

Terry: No, it’s quite flat round here.

Tim: And your background if you’d been out travelling, you’d have been interested in going round Sherwood Forest I presume, like it says on your ‘About’ pages on your favourite locations.

Terry: Yeah, that’s absolutely correct. It was my grandfather’s love for the outdoors. He was a farmer and gamekeeper and he’d often take me out on hikes and we’d camp out in the woods overnight watching badgers and foxes. My grandmother had a big interest in culture and history so they both had a profound influence on me in that respect, in shaping my view of the world we live in. They were immigrants as well, they weren’t born here. They came here after the War. Not long before I got made redundant, I had a health scare, a suspected heart attack and that reignited my passion to the fore for the outdoors and particularly here in Britain. I felt like there are lots of places I want to see and visit and camp out and make the most of it because life’s just too short. While some would say it became an obsession of mine in truth, it doesn’t feel that way for me and just that obsession, that passion for the outdoors, the likes of Twitter, the You Tube stuff, it’s all come together all at the same time to put me where I am now so I do feel very fortunate and very grateful for the followers I have that have put me where I am today. It’s encouraging for me as well how they enjoy the sights I see and share.

Tim: Had you travelled before to the Lake District and Scotland?

Terry: Yeah, I did go out but not as often as I’ve done in recent years. Forget what I do now in my work but as a hobby, it’d be as often as possible. I’d work extra shifts at work so I could earn the hours which would then give me more free time off.

Tim: Was that mostly in the Lakes?

Terry: Yeah, mostly in the Lakes. I spent a lot of time in the Peak District and Snowdonia. There are lots of other places I’ve not been to. I’d like to. I’m recently spending a lot of time in Scotland but my heart really lies in Cumbria. I don’t want to say the Lake District because it’s a cliché but it’s the whole county, I love all the aspects of the county because you’ve got the Howgill Fells as well and the Northern Fells, the coastline, the Southern Lakes with the limestone country and the forests. It’s just something there. I often joke I was probably born a shepherd in a previous life because of the time I spend out on the Fells but it’s just there in me. As much as I love other places and they’re just as spectacular or arguably more spectacular, there’s just something about Cumbria that really pushes the buttons for me. That was one reason why I wanted to do this film about Scafell.

Tim: How do you go from having a health scare and then deciding to do something full time, to deciding it’s going to be about Scafell?

Terry: They were all like regular corporate and tourism videos that I was doing initially, bread and butter, I was just getting my foot on the ladder on this new career I was on. But where the idea of the Scafell film comes from, it’s really with a frustration that we never see much of the British countryside looking spectacular on the television or on DVDs you get in shops. It’s like the crews had turned up because they’re on a daily or hourly rate, they get the shot done and then they go home and that’s the Lake District. Don’t get me wrong, it does look beautiful whatever the weather and it can look nice but as a backpacker, as a wild camper, I know it can look a million times better. I see these sights from my tent on the Fells. Born out of that frustration is what led me to do this Scafell film, I wanted to show the Scafell through the seasons looking at its best and worst. But with my interest in history and culture as well and people, I wanted it to be as much about the people that live and work around the mountain as well and play on there because people have arguably shaped the mountains that we see today in the Lake District, sheep farming for example. So it’s something I always wanted to see because it’s just not out there. Recently I’ve been working extremely hard doing lots of night time laps of the area. You see that two a penny on these videos on You Tube or in California, the lucky beggars have got a lovely dry eyed desert to go out and see billions of stars. We don’t really see that here but we do get some nice dark skies. I can’t think of any particular productions where we’ve seen lots of night shots of places like the Lake District and that again I’m keen to get into the film and why I worked hard producing those night time lap sequences is because it’s another aspect of the area that’s stunning. It’s not just beautiful in the day; it’s beautiful at night as well when you see the Milky Way coming over. Again I suppose I’m revealing that passion and love for the area because I want to inspire and share this with people so it enlightens them, makes them wish to care and protect the area and more importantly, visit the area and look at it in a different way. If they’ve not been there before, they may want to go after seeing this.

Tim: Here’s a question for you. Scafell is notoriously difficult to photograph and you see very few photographs that get a good representation of what it’s like. I can think of a handful I’ve seen and I’ve seen a lot of people trying. If you’re going to choose somewhere for a video, why Scafell over other possibly more attractive options?

Terry: I disagree with that. I think the Scafell are photogenic. It depends where you go. A lot of people don’t wander far from the beaten path. There’s Yeastyrigg Crag which is on Esk Pike that gives you this formidable full on view of the Scafell on the Upper Eskdale side. It looks brutal. I often compare the Scafell as the ugly prince with the Queen that is Snowdon and the King that is Ben Nevis. The obvious ones from Hardknott and so on but you get this amazing view of the Scafell where it does look like a wild large mountain. High Gate Crags which in Upper Eskdale, there’s a real sense of isolation and being remote there and again it affords a fantastic view of the Scafell, a much more intimate view. However, when you go to the Wasdale side, it does look like large grassy hills with some craggy knobs on the top, totally different character and it’s often that side where you see all the photos of the Scafell and not so much the wild side. And that’s because it’s easily accessible from the road and people think the usual shot with water there in the same scene to frame the shot. But also you have to bear in mind that the weather plays a large part in the view of the area, the whole massif but also where the sun sets. Generally through the summer months, the warm dry months, spring and summer to early autumn, the sun sets along the line of the Wasdale Valley. It lights up that side of the Scafell and it can look very lovely and pretty, particularly the Screes nearby which all light up red in the late autumn because the sun’s setting in perfect alignment with the valley. That’s really rather exciting, there’s not many valleys you get like that in mountainous areas. When you get to late autumn and through the winter and early spring, the sun sets on the other side of the Scafell where it lights up Eskdale and lights up all the crags and knolls of the Scafell on that side, the wild side as I like to call it. Again, that’s completely different and it’s just as spectacular. If you’re on the other side, you’re dark. Unfortunately, it’s hard to get dawn shots. It tends to be early winter where the Scafell can look best at dawn because the sun tends to rise in alignment with the Crinkle Crags and as it creeps over the gap, the cull between Bowfell and Crinkle Crags where three tarns is, that cull thankfully gives enough dawn light to light up the majority of the Scafell on that side, that facet of it. I suppose in a roundabout way if you want it nice and easy, it is hard to photograph but if you persist and think outside the box, it’s easily achievable.

Tim: Do you think this is one of the downsides of the Lake District representation in landscape photography, the fact that all the photographs are taken from places within a mile at the most from a car park?

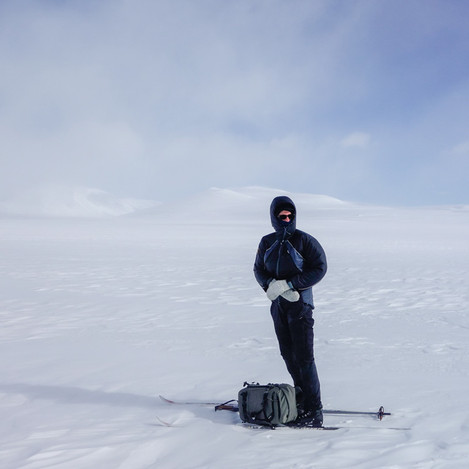

Terry: Yeah, absolutely. I can only think of a couple of photographers I know well in Cumbria base that actually get away. Most don’t walk more than a mile from the car. These guys camp out like I do. It’s their love and passion for the area and they get some amazing photos of the Scafell and the Lake District at large. They’re doing much the same as me but sadly, we’re a minority. I go out in all seasons. I’ve camped on Bowfell summit. It’s a rocky place, you can’t always put a tent there but in the height of winter, there’s lots of deep snow so you can get a tent up there. Sub-zero temperatures, I’ve encountered –18 and –19 wind chill up there, absolutely freezing but it was well worth it for some of the shots I got. I’m a crazy minority breed in that respect to most people but it’s just normal to me.

Tim: Have you been wild camping before you were doing the video?

Terry: Yeah, that was my hobby, backpacking in general so the interest came from that with video and everything else.

Tim: When you’re going out with your video, I’ve wild camped with my large format gear and it ends up quite a hefty collection of equipment by the time you’ve finished getting everything in a pack. How do you travel? Do you typically go out with a tarp in the summer or are you still a tent...?

Terry: I switch about. A tarp in the summer or a bivvy but when it comes to winter, it’s a tent every time. You get a bit more shelter. Arguably a bivvy will be just as good because it’s a bit more bomb proof wherever you can lie down and feel you can sleep the night, a bivvy will go there. With tents, you have to think carefully where you’re going to pitch it, is it quite sheltered.

Tim: It’s a long night in a bivvy though.

Terry: I get a thrill from that sense of exposure to the outdoors; it makes me feel much more in tune with the area, the sight and the sounds. I don’t particularly enjoy being cooped up in a tent because you’re cut off from it all. But a tent’s handy as well; I may sometimes base camp so I’ll make a camp and then go from there to save a bit of weight on my back. At the moment, this winter my pack was in excess of 30 kilos and that’s made me think very carefully on the kit I take and why. With regards to photography, I’m a big fan of these mirrorless cameras now.

Tim: Are you using things like the Panasonics?

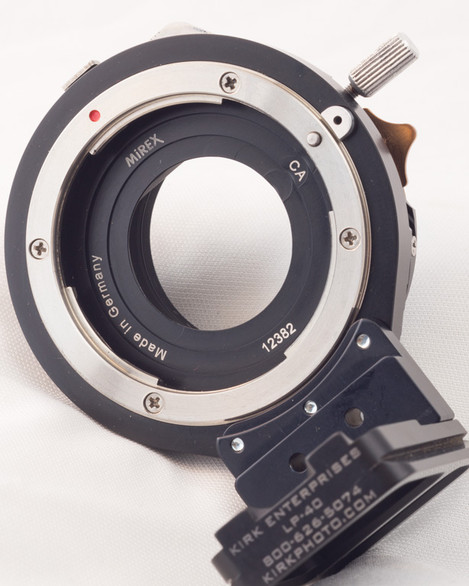

Terry: No, the one I’m using at the moment, I chop and change my mind quite a bit, but the one that’s done me fine and I really enjoy using but I’d prefer a few more features on it is the Canon EOS M. It’s the only mirrorless camera they do but it’s tiny, it’s the size of a compact but spec hardware wise, it’s essentially the same as their mid-range DSLRs.

Tim: Incredibly cheap at the moment, I saw someone get one for £200 at a photography show.

Terry: Exactly. I still have a DSLR as well because with the mirrorless camera, you don’t have the viewfinder which is a bit of a pain sometimes because you have to rely on the light view screen. You can use Canon lenses with it but it defeats the object of using a mirrorless camera because it becomes a lot bulkier. Their own specific mirrorless camera lenses are not ideal really for photography when it comes to focus. You can’t see your focus numbers on the lens, I’m mimicking it already, you have to look through a viewfinder but you can’t do that on the Canon EOS M which is annoying so I do flip between the two. It depends how much kit I’m taking and why I’m on the trip so if I’m taking not as much video kit as normal, then the DSLR comes with me. If I’m taking a lot of kit with me, then the EOS M comes with me.

Tim: So you use a 5D for the video?

Terry: I did have one and I got rid of that, I’m using a 600D at the moment. I’ve been using the 600D primarily for time lapse, not really for the photography although if it’s all I have with me, then I will use it if there’s a shot I’d like to take a photo off. The priority is the video.

Tim: Do you take out sliders and things like that as well?

Terry: I used to take filters but I don’t bother now.

Tim: Sorry, sliders.

Terry: Yes, I do, it’s a professional 3 sensor video camera you use. Sadly DSLR video’s not very good. I know it’s all the rage at the moment and it’s great for online use but when it comes to DVD and TV or even where the Scafell film’s being shown on the IMAX screen, that’s where the shortcomings reveal themselves. You get a lot of codec fizz noise in the image.

Tim: Which camera is that?

Terry: If you use a DSLR for video, I don’t, you have more codec issues. It surprises lots of people when I mention it to them but 90% of DSLR don’t actually record true 1080 HD video, it’s a few lines less and of course it’s compressed and then you get a codec fizz in there. So I use a dedicated three chip professional video camera which is not a Canon, it’s a Panasonic. And it’s bulky and heavy but ensures I get the images I’m after and it has a very good wide dynamic range on it for a video camera.

Tim: That’s what you need for some of the shots I’ve seen you getting.

Terry: Yeah! I’d love it to be much better. A DSLR does afford a better wide dynamic range; it’s just all the shortcomings you get with that in terms of video. They’re not quite there yet. I’d love them to be because they’re smaller and lighter to carry but there are other things I have to consider as well. Sound, for example, is equally if not more important quite often than the actual images you’re capturing. DSLRs you’ve got your shortcomings there on the sound. You need dedicated audio recorders and it all adds more bulk and expense, where my dedicated video camera it’s all there built in.

Tim: I just do a bit of amateur video now and then and I ended up spending about £2500 on my audio gear and about £200 on the camera. You can save money on the video gear if you can compromise slightly but you can’t save money on the audio stuff.

Terry: But for online use, there’s nothing wrong with DSLRs and a relatively cheap microphone, it does the job but that’s been a steep learning curve for me in the last couple of years. I can’t do that for when stuff’s going on DVD or in cinemas, it’s got to be much better.

Tim: Out of interest on the sound side, the one thing most people get when they go out and do a video on the side of a mountain is wind noise, regardless of what they use. What’s your recommendation for trying to get some decent recording when you’re in the inevitable Lake District gale?

Terry: Again, this adds more bulk but not so much the weight, I have to add, I use a large Blimp. It’s just a large case; the microphone sits inside that on a suspension system so there’s a filter over the microphone that should cut out a bit of noise but not too much. The Blimp itself should cut out quite a bit of wind noise and on top of that, I put a furry dead cat, as they call them. That keeps the wind out and it surprises you how good the sound is. The wind just sounds like a deep breeze.

Tim: Do you know the Unsworths, David and Angie? They do recording now and they introduced me to the Blimps and they were very impressed with the sound quality.

Terry: I use it all the time now, unless it’s a nice day and then it’s fine. When I’ve interviewed people out on the Fells, normally I would wire them up with a tie clip mike but that has limitations if it’s going to be windy. If it’s going to be windy, the Blimp comes out instead, or I’ll use both just as backup and then I can work with both when I get back home.

Tim: You can mix some ambient sound in because the tie clips are quite tight sometimes.

Terry: Yeah, that does make a difference. If I’ve not used the Blimp, I’ll use the internal microphone, the video camera, but that’s not always ideal anyway. The quality on there is not particularly great but it’s good enough for ambient stuff if somebody’s talking through a tie clip mike, you won’t really notice.

Tim: Getting away from the technical side of it and back on the hill again, what do you compromise on when you’re out because of the weight? Do you compromise on your camping gear or do you always make sure you’re fairly comfortable?

Terry: That’s a tricky one. My base weight for my camping gear is not even four or five kilos. It’s a lightweight tent, it’s all top end gear, I’m quite fortunate that I bought some of this stuff myself the last few years but also the sponsors that are involved with the film produce good kit so they donate kit to me enabling me to carry on doing the film. So I’m quite lucky in that respect. With the tent, the sleeping bag, a decent mattress to keep me warm and comfortable ... I need a decent mattress because I’m going to be out for nights and nights, days on end, I need my sleep. I need to get a good night’s sleep to rest and recover or whatever the terrain and the weather’s throwing at me, so I don’t compromise too much on that front but I probably do with food. I don’t really take nice tasty warm meals with me, I’ll take things like dried fruit and nuts, chocolate drinks so I’m getting my nutrition, all my vitamins and minerals and my calories but it’s not exactly something I look forward to at the end of a hard day’s slog when I want my steak and chips or anything really that would be nice and warm inside me! But instead, I’m munching on dried fruit and nuts. So I probably just compromise there more than anything else.

Tim: How many days do you reckon you’ve spent on that mountain to try and get the footage you needed?

Terry: I’ve not been counting, let’s put it that way! I often get joked that they should do a Council tax ban for wild campers now with the amount of time I’ve spent out on the Fells in a tent! I’ve spent more time out on the hills than I have in my own bed at home so it’s a lot and it’s not all good either. There’s been many periods where I’m cooped up in a tent all day or on and off, mostly in a tent for two or three days because of the weather. I’ve got to take the rough with the smooth. I’m not a stubborn minded person but I’m bloody minded when I want to get a certain shot of the Scafell so I’ll often wait and wait for two or three days before thinking of giving up and moving on. Or I repeatedly go back to the same place chasing that special view that I want to capture. Eight times out of ten, I get it but eight times out of ten most of the video I capture is not planned anyway; it’s just what I see as I’m out walking and camping.

Tim: That was going to be one of my questions. A lot of photographers like to try and plan their shots in advance and my experience has been that some of the best moments just happen and you need to be ready for them. Has that been your experience?

Terry: Yeah, absolutely which is why I say 80% of what I’ve captured has not been planned at all. The simple reason for that is we can’t control the weather or the light or the air clarity we’re going to see. We can’t control the colour of the land in terms of the seasons. You’ve got to go with the flow and that’s how I am when I’ve been filming people out on the Fell, that go with the flow. There’s not too much of a script. There’s a rough outline of what I want them to talk about but I go with the flow and it’s much the same with capturing the images of the Scafell because I go with the flow. I have a little list of what I’d like and I’ll be mindful of that and keep aiming for it. If I don’t get it or I’m not happy with the shot I’ve got I might try to capture it again but it’s all about being out there in that moment.

Tim: The premiere is at the Rheged and I presume you’re getting pretty close to finishing the editing. Have you started thinking about what to do afterwards or are you just going to take a bit of a break to recoup?

Terry: I can’t afford to have a break, to be honest, I’m on a very low budget for this film and I’ve invested a lot of time. It’s taken over my life and taken quite a bit of my money as well. I didnt want to start working again straight away but the projects I’ve got lined up for this year are nowhere near on the scale of what I’ve been doing with the Scafell or as ambitious. Deliberately so because it’s easier work and I need a rest. That’ll be my break, just easier work, still working hard but working on this Scafell film has really knocked me for six. Physically, my body’s going to be thankful when it’s all over but in my heart, I admit I think I’m going to be really rather sad because of all the friends I’ve made there, getting to know the area much more intimately than I could possibly have ever imagined before starting on this project. The stuff I’ve got lined up, I’m doing a backpacking DVD with Chris Townsend in the Lake District, another Lake District based DVD with Mark Richards who’s the author of the Lakeland Fellranger series books and friend of Alfred Wainwright. And I’ve got some other jobs as well, just regular bread and butter work but nothing lined up now that’s on the scale of what I’ve been working on with the Scafell.

Tim: So theoretically if you were to do another one or a couple if it were a series, what other Fells would you choose?

Terry: Originally I wanted to call this ‘Portrait of a Mountain Scafell Pike’ but if I remember rightly, there’s a copyright on that so I changed it to ‘Life of a Mountain.’ I originally envisaged a series, the series being Scafell Pike, Snowdon, Ben Nevis but I didn’t want to run away with myself because I’m not sure how people are going to react to the film. It’s all subjective but if it proves popular, then great and I’ll seriously think about doing another one. Whether it would be Snowdon or Ben Nevis, I don’t know. My heart says Helvellyn; I’d like to do Helvellyn.

Tim: There’s a lot of life there.

Terry: But my brain is saying maybe go for Snowdon and leave Ben Nevis till last but I’m torn. I’d like to do one about Helvellyn personally and if I was, I would start on that late this year in the winter and carry on with that. We’ll see, it all depends on how well the film’s received. Thankfully, I’ve done some test audience stuff and they’re thrilled, it’s exceeding a lot of people’s expectations and I’m pleased with that because even though I do these little PR shorts for social networks, I’m deliberately holding back the true scale and depth to the film. There’s a lot going on but it’s not as in-depth as I’d like it to be because it’s only two hours. I could’ve done it as a series.

Tim: Director’s cut coming?

Terry: No, the two hour cut is the director’s cut. I really struggle to get everything in that without spoiling it with its emotive power. I want to strike the balance between it being a spectacle of the mountain through the seasons but equally about people, stories and their experiences. I was a little conscious about getting that balance right but thankfully with the test audience stuff, they’ve given the thumbs up. I don’t want to sound like I’m boasting about it but I’ve been absolutely over the moon with the feedback, it’s been such a thrill that it’s touched people deeply. Some people even said they shed tears and that astonishes me, stuff like that because I’ve become immune. I’ve seen the footage over and over again. Anything involving people might be quite emotionally moving, I’m not seeing that, I’m immune or whether a particular shot of the landscape or sequence I’ve put together is moving for people, it’s all lost on me.

Tim: It must be quite sad because I get this with my photography at times. You never have the effect that you would like your audience to have on yourself, you never see the picture as a stranger would see it.

Terry: No, and I get a thrill from that. I recently showed a selection of people on Twitter a ten minute clip from the winter chapter in the film and I don’t think it’s a particular highlight of the film but they loved it. They went mental. Part of the film I think is a highlight; I’m wondering if people will think that’s a highlight but it just shows you how subjective it is.

Tim: It is. If it’s anything like the audience we have for the magazine, some people say they love it and some people say they don’t like it but they say they love it and don’t like it about completely different things. There’s no consistency at all. Its life at the end of the day, we can’t all like the same music, we can’t all like the same art so as long as the overall content as a whole satisfies most people and they can find something within it that makes them sit up, and I think that’s a win.

Terry: Absolutely, you took the words right out of my mouth, I couldn’t agree with you more. I do feel what’s gone in my favour with this project is that there are lots of characters and stories in the film so there’s something for everybody. If you have no interest in backpacking, that’s all right because there’s another part of the film that’s not featuring backpacking, it’s featuring a shepherdess or a climber or mountain rescue. I’ve got so much in there; it boggles my mind thinking about it now, how I’m going to get it all in. But it’s good stuff.

Tim: We could talk forever about this stuff but don’t want to take up more of your time. Looking forward to following what you do next and how the video is received. Many thanks

On Landscape are also helping the Rheged in Penrith to put on a show of a few images, a talk and a workshop to support the premiere of a film about Scafell Pike. It’s called “Life of a Mountain” and we’ve interviewed it’s creator Terry Abraham in this issue. You can find out more about the event at the Rheged website including the workshop on Ullswater Steamers with Mark Littlejohn, a talk by David and Angie Unsworth and a small exhibition of landscape photography including photographs by Colin Bell, Mark Littlejohn, David and Angie Unsworth, Tony Simpkins, Roy Fleming and Terry Abraham. The Rheged are also offering the opportunity for people to exhibit their own work for which a booking form is available.

Joe Cornish and David Ward Discuss Photos

Last week we ran a webinar with David Ward and Joe Cornish where each photographer chose three of their colleagues images to discuss. The video is now available on You Tube but we've transcribed the content and included the images at higher resolution here.

Harry Callahan Exhibition and Catalog

"I know what you're thinking: 'Did he use two sheets of film or only one?' Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement I've kinda lost track myself. But being as this is a Deardorff 8x10, the most powerful camera in the world, and would blow your D800E clean away, you've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do you, punk?"

- filed under "Things Harry Callahan might not have said"

So I guess you know I'm not talking about *that* Harry Callahan here but to most people and many photographers, you mention the name and this is what comes to mind. Which is sad in a way as Harry Callahan was undoubtedly one of the most important photographers of the post war period. To put things in a little context, the start of the century saw Weston, Adams and the like eschew the 'creativity' of pictorialist style in order to use the camera to record untainted reality. The difference in Harry Callahan's approach to photography was that he used the camera as a tool to investigate his own ideas and environment. He found a small set of subjects, ideas and techniques and worked them repeatedly to find out where they took him. This introspective approach to photography produced some very novel, modernist work.

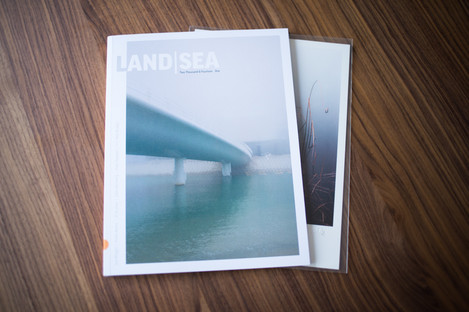

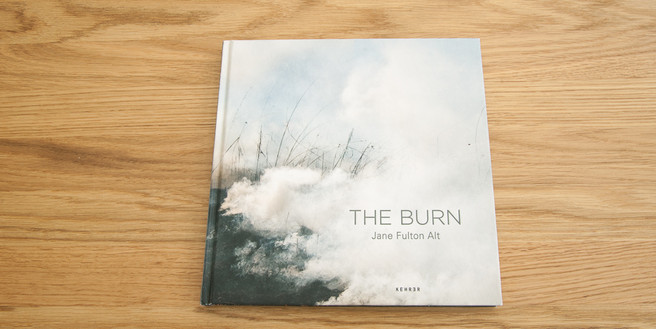

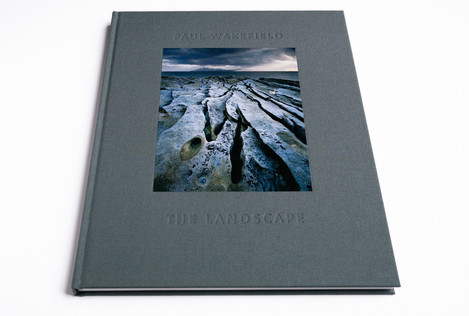

Land|Sea Volume One

editor - Obviously we love Land|Sea but we wanted to put it in the hands of our prospective audience and ask them to give an honest opinion. Paul Arthur fit the bill for a colleague who is always brutally honest (thanks for all those occasions Paul - I think)

In the middle months of 2013 I heard rumour of a new book about to break onto the scene, written by a friend I had made very early on in my landscape photography career. Many of you will have read the review of Dav Thomas’ book, With Trees, and you may even be lucky enough to own a copy. The content of the book was simply wonderful, but the presentation and production of the book was something that was interesting in itself; the book represented the first publication by a publisher that styles itself as a producer of “Quality Landscape Photography Books”, and in the months since then, TripleKite Publishing has announced a number of exciting book projects, and I know that more are in the pipeline.

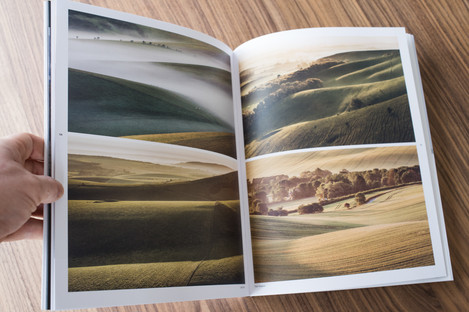

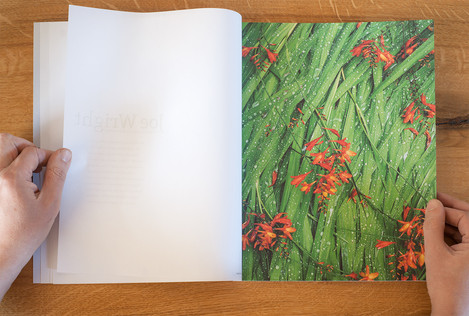

One of the book projects that TripleKite has announced and now produced is the Land|Sea book in collaboration with On Landscape. TripleKite were kind enough to provide me with a copy of the book so that I could review it. So when I arrived back home last week I was delighted to see a discreet packet waiting for me on my doormat. Inside the carefully thought out packaging was the book and also a beautiful print to accompany it, available for a very reasonable extra supplement.

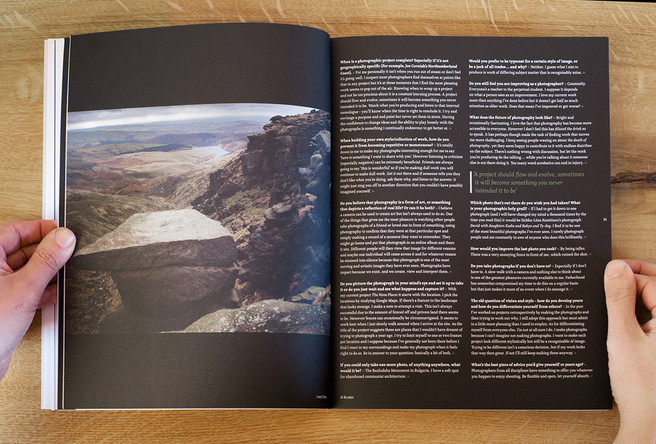

This book is an unusual prospect for the reviewer as firstly it contains work by a number of different photographers, and secondly because it is clearly designed to be the first volume in a series, so I feel it is better to discuss the work and the production separately as the production is likely to remain constant for future volumes. The book is very nicely printed, and the variety of papers and printing methods provides a very tactile experience. The inside is a combination of very thin paper for text sections and sumptuous matt paper for the images, and combined with the silky matt cover, it gives a feeling of being a high-quality publication. The dimensions and bulk of the book remind me of publications like the British Journal of Photography and in some ways I think that this should be viewed as an overachieving magazine, rather than a book.

Land|Sea is something of a compilation album, but I don’t want you to think of it as a Greatest Hits type of affair; they’re trying to do more than that. The collaboration with On Landscape has enabled the publisher to select a small group of photographers that are very different from each other, and that are able to demonstrate high levels of skill and creativity in their own area of the landscape photography spectrum. So perhaps this book is more of an anthology designed to give a flavour of the variety that is out there, rather than something designed to illicit a “Wow!” response.

Each of the photographers featured in the book (Joe Wright, Valda Bailey, Al Brydon, Giles McGarry and Finn Hopson) get eight pages in which to show their work, and with each is either a short essay about their method and philosophy or a question and answer session, very reminiscent of On Landscape’s Featured Photographer articles. There’s also a very good essay by Paul Kenny at the end of the book: a discussion piece about the relationship between Landscape, Photography and Art. Whilst an enlightening read that helps us to understand how Paul came to produce the work in the way that he does, I would have perhaps preferred him to write a piece about his views on the work represented in this book.

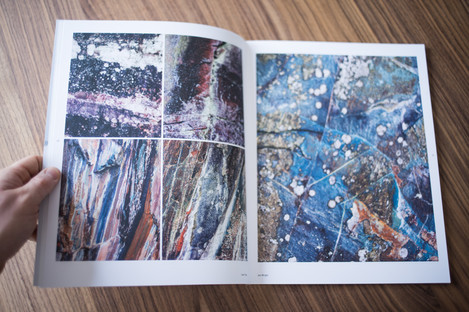

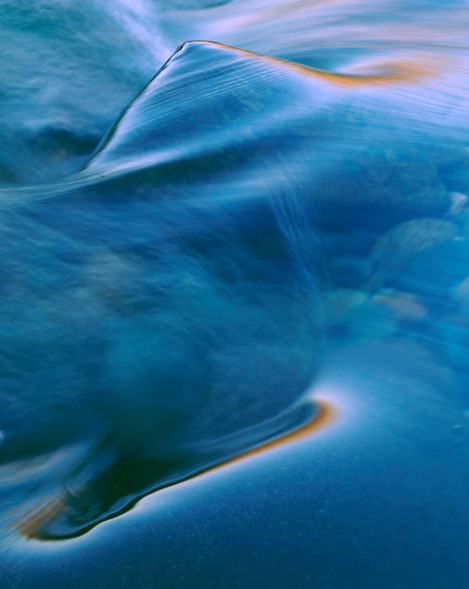

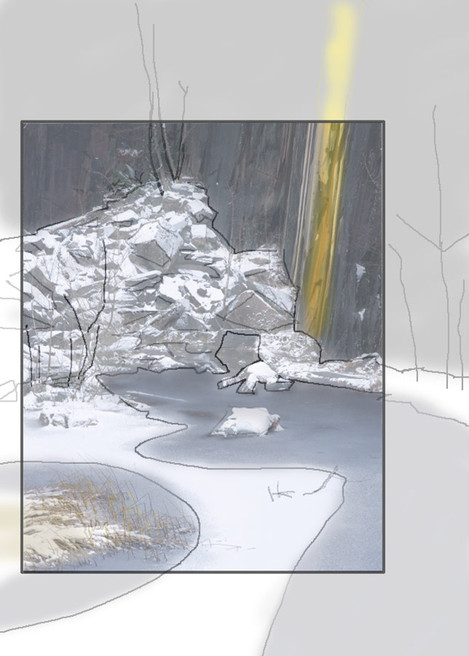

Joe Wright

I have spent time photographing with Joe in the past, and I have always marvelled that such quiet and gentle work can come from such a giant of a man. The first image in the main body of the book is a simply stunning image of a pile of rain-soaked Crocosmia, with glistening water droplets and rich, juicy colours. I was so pleased to find this image at the front of the book, welcoming me, warming me and encouraging me to sit down and read the rest of the book in one sitting – not something I’m prone to do. Alongside Joe’s thoughtful prose on the virtues of the British landscape is a pair of literally reflective images that sit well opposite a peaceful, almost monochrome winter woodland scene, before an explosion of colour in the rock studies over the page. Describing these images as simply rock studies doesn’t do them justice however, as the rich colour relationship between the five is both pleasing and jarring and demonstrates the pre-visualisation of the set as a whole.

Joe’s final pages are devoted to a pair of images (my favourites) that show his ability to spot images where others might not, and how he can combine still and dynamic elements to create images that confuse and titillate the senses. I’m looking forward to seeing more of Joe’s work in print in the years to come.

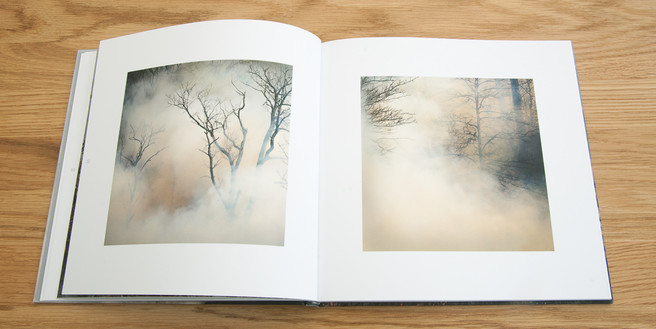

Valda Bailey

I have often felt that amongst arty types, photography is viewed as a poor cousin, a runt of the litter, and not particularly artistically valid. Indeed, on reading a book titled “101 Things to Learn in Art School” recently, I saw an illustration depicting a camera with the title “Always document your work” – the implication being that photography is only for documenting art, and cannot be art in itself. Paul Kenny’s article in this book discusses that photography can be art, and that the subject isn’t important, but other less tangible things are. Valda’s work for me perfectly illustrates how it is possible to use the medium of photography to create “Art”, and I can’t see how it could ever be accused of being merely descriptive and illustrative in the way that photography often is.

I find it difficult to describe adequately the images that Valda creates. She makes, in camera, images that in my view aren’t photographs: they are individual artworks created with a camera. I think that photographs in the traditional sense can become art if they are viewed as part of a portfolio that has something to say more than just “this is a pretty picture”. This simply isn’t the case for Valda – each one of these images deserves in my view to be considered as art on it’s own, let alone as part of a portfolio. Her images are rich in colour, lush in tone and are long-lasting because of their confusing nature. I can look at most traditional photographs and know pretty much how they were made, but with Valda’s I mutter with child-like wonder “How on Earth did she do that?” I would be doing her a disservice to try to describe these images to you, so I won’t. But you should definitely check her out.

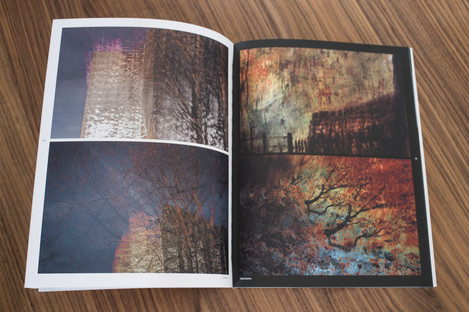

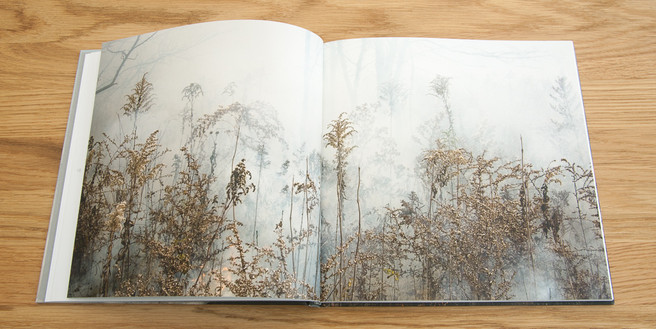

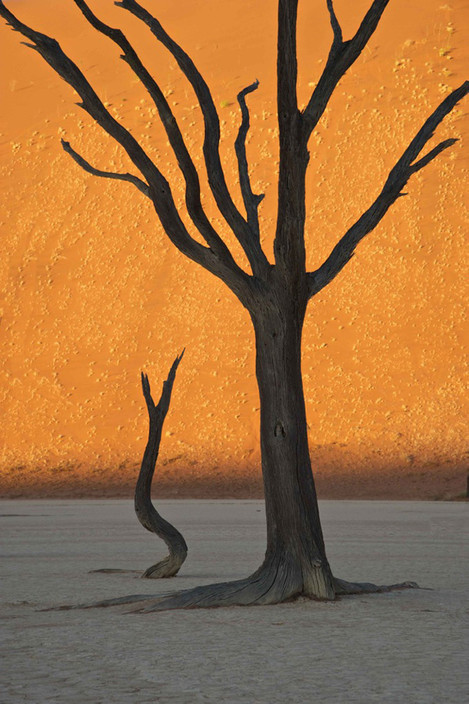

Al Brydon

The last ten years in landscape photography has mostly been about big vistas and bright colours, and the mainstream photography press has perpetuated this because it looks superficially appealing on the page. It’s always a relief to me then when I am allowed to look at work that is less colourful, less contrasty and that has less obvious compositional structures. Those images permit me to have more than a “Oooh” reaction; they let me stroke my imaginary beard instead and ponder them. Al’s images are predominantly dark and brooding, they demonstrate careful and well thought out solutions to compositional problems, and there are strong lines of energy movement though largely static structures.

The pair of full-page images in the middle of Al’s chapter of the book are particular favourites and complement each other well. I find them inviting and they make me want to explore those places and find my own images too, but not because I want to take the same, but because his images make me believe that there are so many possibilities in those places. The set hangs together well in tone and style, although I’m not convinced all of the images work well with the printing method employed in creating the book. The matt paper on which the images are printed is actually quite reflective and I found that I had to move to the window to get the best out of Al’s darker images. It’s a minor thing indeed though, and I found the imagery and the humour in the accompanying interview particularly enjoyable.

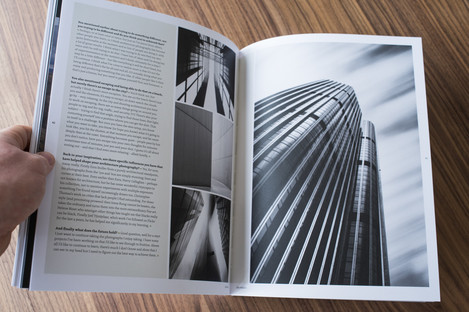

Giles McGarry

Giles is another photographer with whom I have been lucky enough to spend a day over the last couple of years. We went out in the rain around central London and came back with pretty much no images at all, but we spoke about our mutual love and respect for architecture. Architectural photography is my game, and so I take real pleasure in not only the subject matter of Giles’ photography but also the way in which he approaches it – a way completely different to mine.

Some may question why a portfolio of architectural photographs is appearing in a book of landscape photography, and they may have a point, but a prospective client of mine hit the nail on the head a few years ago when he said of architectural and landscape photography: “They’re the same thing, right? You’re looking for the same things in the photographs.” In this respect, the artier side of architectural photography should feel right at home alongside images of the landscape.

Giles’ love affair with line and texture is evident in this portfolio of images. The techniques he employs in making his images may be quite common these days since the rise of the Big Stopper, but this level of attainment is not at all common. His employment of both high and low key, angular and rounded shapes, smooth and jagged textures give a nicely balanced set that leaves me wanting more.

onlandscape.co.uk/GilesMcGarry

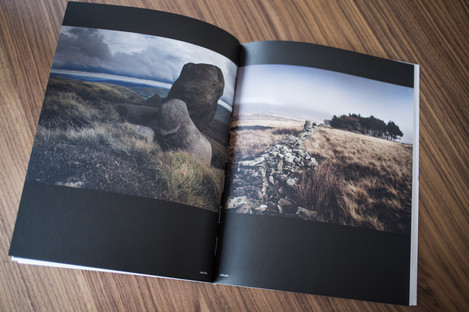

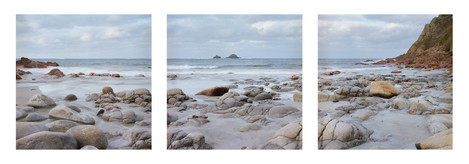

Finn Hopson

I hope Finn will forgive me for revealing that out of all the photographers featured in this book, he is the only one I hadn’t heard of before. This is I think one of the strengths of the book as a whole: it introduces you to a selection of photographers, different in style, and you probably won’t have heard of them all.

One of the difficulties I have with my landscape work is finding the time to get out and make images, and I have noticed that the better landscape photography output usually comes from photographers who make images close to home. This is no accident, as I think real success comes from repeated visits and getting to know an area intimately. Finn is another to add to the list of image-makers who show that regular visits to the same area yield stunning results. His peaceful images of the South Downs stir emotions in me, and certainly make me wish I lived nearby so I could go for long walks in those places. In my view, a successful image is one that conveys the feelings of the photographer or that makes you imagine what it is like to be in that place. The final spread of Finn’s chapter feels like it should be a montage of images to accompany a great piece of Elgar, a combination designed to make you fall in love with England and its landscape.

I feel that all the photographers featured should be proud to be involved in the first volume of hopefully a long series. The premise itself is a sound one: create a high quality showcase of skilled landscape photographers, and I hope that the series gets the attention and sales it deserves so that there are more editions to put beside this one on the shelf.

Route 66

Route 66, The Mother Road. Taking in eight states, the route once epitomised the American dream. In the forties and fifties it’s travellers would journey from Chicago in the east to Los Angles in the west. The reason for the journey was the journey itself. The image of Route 66 was its cars, hotels, diners, gas stations and the people that made the experience remarkable.

Roll forward more than half a century and things are now very different. In the seventies and eighties the US interstate roads by passed the towns and cities along route 66, which together with the road itself, fell into decline. Today Route 66 exists only in sections, but those sections are really worth visiting. Much of the route has become the interstates i-55 and i-40, roads which are also worth travelling. Many of the towns and cities from the heyday are still there. Some are in better condition than others but all are worthy of a look. And whilst much may now be faded it is still the cars, hotels, diners, and gas stations, not forgetting the people that continue to make the experience of today fascinating. Perhaps in a different way to how it was all those years ago, but a journey along route 66 is still unforgettable.

Kyle McDougall

This issue we're featuring Canadian photographer Kyle McDougall who has some beautiful imagery of Ontario and it's surroundings (and more!).

If you could also tell us where you live and what you do for a living that would be great.

I am a landscape photographer based out of the Muskoka region in Ontario, Canada. For a living I run my own business, which includes work as a cinematographer and editor for television/commercial projects and also landscape photography focused on writing, prints and teaching private workshops (soon to be group workshops).

Can you tell me a little about your education, childhood passions, early exposure to photography and vocation?

I grew up in a larger city in Ontario, Canada, but as a child was exposed to nature on a regular basis with trips to the family cottage further north. I spent my summers exploring the forests around the area as any child would, fishing, swimming, hiking… in search of the next great adventure. I guess I would say that I always had a special connection with nature although it was never exposed, or I never understood it until later in life. After finishing high school I moved out to the Western Canada to spend some time in the Rocky Mountains, which is where I bought my first DSLR. I always had somewhat of an interest in photography, but living in the mountains is where my passion really started to develop. I started creating images whenever I had the chance, and was always excited regardless of the results. It was only natural that with my love for the outdoors, almost all of my photography was focused on my surroundings. I enjoyed the personal approach to creating images and the fact that the results were a reflection of my dedication and commitment. Out of this grew an interest in cinematography, which lead me to move back home and attend school for Film Production. I spent the next two years training in still photography and motion picture film, specifically super 16mm. After graduating I started work as a cinematographer and editor for a couple of television shows, and also found my direction with photography. This is when my images started to focus solely on the land and my passion for nature started to strengthen.

What are you most proud of in your photography?

I would say what I’m most proud of is the journey I’ve created through photography and my growth as an artist. Any creative person knows that no matter how passionate you are about your craft, there are always low points, and what matters most is staying passionate, persistent and curious. It’s the journey that has the biggest impact on your images, therefore it’s extremely important to stay true to yourself and not try to follow someone else’s path. Because of this, photography has evolved into something so much bigger then I ever thought it would be. It has taught me an immense amount about both the land and myself and has grown my appreciation for the simple things in life immensely. I know I still have a huge road ahead, but am excited for the challenges and excitement that the future holds.

In most photographers lives there are 'epiphanic’ moments where things become clear, or new directions are formed. What were your two main moments and how did they change your photography?

I think the biggest moment was when I realised the importance of creating images for myself, not simply trying to please others. I think in the beginning, we all reach a point where we become proficient enough to create images that are technically sound, and we are left searching for other ways to improve our photography. For me, this is where I started to realise the importance of personal vision. The closer I looked the more I started to see and as a result my images started to possess more personality as my appreciation for the land grew stronger. It was this realisation that an image doesn’t have to have bold colours or a dramatic sky to be “successful” that had a profound affect on how I work. I think it’s only natural that starting out we all try to create images to please others in hopes of gaining acceptance. Unfortunately the only thing this does is leaves us creating work that lacks uniqueness and self-reflection. When we strip ourselves of pre-conceived outlines and rules, our images grow stronger. The other moment would be the realisation of how important the experience is. I think we all get to a point where we are so set on creating a great image that we try and force things, forgetting why we are out in nature in the first place. Because of this, the experience becomes un-enjoyable and any images we do create are certain to be affected by it. Now, if I’m at an area and something isn’t working, I simply take a break, and enjoy my surroundings. I will find an image when the time is right, and usually that’s only when I have a clear mind. Both of these things have taught me to take a slower, more detailed approach to creating images, and in the end have shaped the direction I’ve gone with my photography.

Tell me about why you love landscape photography? A little background on what your first passions were, what you studied and what job you ended up doing.

I love landscape photography because it has influenced me to explore places that I may not have otherwise ventured. It has been a big reason why my passion for the outdoors is as strong as it today. It has pushed me out of my comfort zone on many occasions and has taught me many lessons. There is nothing more exciting then going out with my camera to explore for the day, either at a new dramatic location, or somewhere close to home that I’ve visited many times before. It’s the curiosity of what I’ll find that drives me. Like I said before, my passion for nature was always there, but I believe photography was the tool that exploited it and grew it into what it is today. I’m fortunate to do what I love for a living, that being photography and cinematography. Most of my cinematography is lifestyle/action sports based for television and has me working outside and traveling throughout North America. While not directly related to landscape photography, I’m constantly learning as I’m behind the lens, composing and using light in similar ways. I feel that it’s played a large role in developing my vision.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography.

The kit I use is pretty simple and consists of a Canon 5D MKII, Zeiss Distagon T* 21mm f/2.8 , Zeiss Planar T* 50mm f/1.4 and Canon 70-200mm f/4 L. I switched to the Zeiss primes after not being completely satisfied with Canon’s wide-angle zoom lenses. The Zeiss 21mm seems to be the lens that is on my camera the most, although I never approach an image from a focal length standpoint, I always visualize first and then select a lens based on what I want to show. I like the Zeiss ZE series lenses because I know I can rely on them to resolve the most detail and produce the cleanest results. The 21mm in particular is the most impressive wide lens I’ve used and captures stunning detail from edge to edge. I’ve enjoyed working with prime lenses as they match my slower approach. They also work great for shooting video with their smooth focus throw. In the future I’d like to keep building my collection of primes starting with the Zeiss 35mm f/2 ZE. When Canon eventually releases a body with more resolution I’ll likely make the upgrade, but for now the MKII serves me well.

What sort of post processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

Like everyone else in the digital age, processing plays a large role in my work, but in varying amounts depending on the image. I strictly use Photoshop for all of my images. My process starts off in Camera Raw where I optimise my “digital negative”, sticking to minor exposure adjustments like black levels, shadows and minor highlight recovery. From there I will apply capture sharpening and remove any lens aberrations if need be. After this, all of my adjustments are done in Photoshop through a series of layers and layer masks. Again, the amount is very much dependant on the image and can be very simple or very complicated. Post processing for me is a way to overcome limitations of the camera and also shape my personal vision. I often use manual blending for exposure issues or focus stacking to avoid lens diffraction. Luminosity masks also play a large role in my processing workflow as a way to target specific tones throughout my image. Every time I process an image I refine my techniques in small increments, even if I notice it or not. All of my images are saved as TIFF master files and then duplicated for printing, web etc. I often find myself revisiting old images as my skill and techniques become more refined.

Do you get many of your pictures printed and, if at all, where/how do you get them printed?

I print all of my images myself up to 17” wide on an Epson 3880. For images any larger I outsource to a local landscape photographer who I have a good relationship with. The printing process is something that holds a lot of value. In my opinion, the image truly becomes complete once it’s printed. I use a range of papers depending on the image but recently have been using Red River’s San Gabriel Semi Gloss Fibre. I also use Ilford Prestige Smooth Pearl. Matte papers are something that I haven’t yet experimented much with but may in the future depending on the image. It’s an exciting process as I always find myself making small refinements every time I print an image.

Tell me about the photographers that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

In our day and age with the Internet we have access to so much inspiring work, it’s almost overwhelming. There are so many talented photographers out there, some with whom I’ve had the privilege of getting to know. Someone who has had a big influence on my work has been Guy Tal. Not only for his images, but also his writings. I admire his passion, mindset and approach towards creating. There have been a number of books that have had large influences on how I work. David Noton’s “Waiting For The Light” was one of the first books I owned that really introduced me to the intricate process of creating an image. I’ve also enjoyed Alain Briot’s collection of books published under Rocky Nook. And of course Galen Rowell’s classic Mountain Light. It’s books like these where photographers really express themselves and their approach that have had the biggest influence on my photography.

What is the landscape photography community/scene like in Canada compared with your perceptions of the US or Europe?

This is a tough one but I would say that the landscape community in Canada seems a lot smaller and because of this possibly tighter knit. Obviously, with Canada’s population being lower than both the US and UK there are less of us landscape photographers around and therefore it becomes easier to get to know everyone who is involved in the scene. I could be wrong on this, but that’s what I would assume. Lately, I’ve noticed more people start to take an interest in landscape photography, which is exciting. You don’t have to go far in Canada to be surrounded by nature, which is a big benefit for us. The amount of inspiration around is endless! That all being said, social media has really changed the way we interact and has opened up the door for us to meet other photographers from all over the world.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs are and a little bit about them.

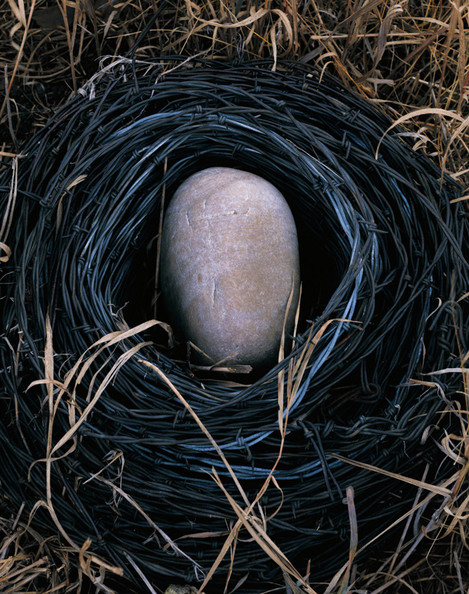

What I consider my favourites are constantly changing the more I create. At the moment, if I had to pick three, these would be them. They are all similar in subject matter, which I think shows the direction my photography is headed.

“The Stand Off” : This was one of the first images I created from a “visualisation” stand point a number of years ago and it really changed the way that I approach my work. I had passed by this area many times and eventually decided to stop and scout out possible images. I was attracted to the lone tree on the riverbank and knew that with where it was located there was the potential to work with dramatic light to create a strong mood. I returned one morning at the start of winter with frost covering the land and mist slowly rising from the water. I waited for the right moment when the tree was backlit and a select portion of the warm morning light had spilled on the foreground. It’s this layering of light and shadows that I feel give images a strong sense of depth.

“The Tree Of Life” : I created this image last autumn at a location close to my home. By far, my favourite time of year to shoot is in autumn when the mix of varying temperatures creates thick fog and mist that blankets the landscape. I’m always attracted to busy scenes and the way that mist can simplify them. I explored this particular area for over an hour searching for the right image. I’ve found that a lot of my images focus on trees. I think they have a lot of qualities that attract me, one of them being lines. I really liked the way that the foreground trees act as a frame and seem to “guard” the centre tree. The bird’s nest in the centre tree was what ultimately completed the image for me.

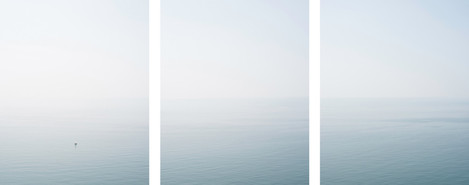

“Winter Warmth” : I spent three days camping at this location, exploring and photographing throughout the days. This particular evening I climbed to the top of a ridge to capture the fleeting light and a vista of the surrounding lake. The first image I created was a wider view, which shows off the surrounding land, but in the end it was this more intimate composition that resonated with me the strongest. I’m always attracted to mixing warm and cool light and the effect it can have on the final image.

If you were told you couldn’t do anything photography related for a week, what would you end up doing (i.e. Do you have a hobby other than photography..)

I would most likely go camping, canoeing or hiking, just without my camera. Or work on one of my personal projects related to Filmmaking (Does that still count?). I’m passionate about telling stories and have a short documentary project in the works focusing on another artist. I think that everyone has a story to tell or at the very least a meaningful message. I really enjoy exploring the possibilities of impacting others through filmmaking. Cinematography really interests me… mainly the power and complexity of it.

What sorts of things do you think might challenge you in the future or do you have any photographs or styles that you want to investigate? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

My plan for the future is to follow whichever path my photography takes me. I haven’t ever had a specific style that I’ve tried to follow; rather, I’ve just let my photography take me in specific directions and embraced them. I really see my work exploring the finer details and more intimate scenes in nature. This is something that over the past couple of years I’ve noticed myself trending closer towards. I really enjoy exposing the amazing scenes in nature that many others miss. I think for all of us, as our eyes and minds become more refined, it’s these details that interest us more rather than what’s most obvious.

How do you work with both moving and still image together and is it possible to do both at the same time?

My photography and video work are very separate endeavours. Landscape photography for me is a very slow and personal process. Most of the time when I head out to shoot I only end up creating one image. Also, there’s the fact that the results are based solely on my own input and effort. When I’m shooting video, it’s usually under very different circumstances. All though I approach this type of work from a cinematic standpoint and spend as much time composing and creating shots as I can, I have to work fast as each shot is just one piece of a scene, which in the end is made up of a large number of shots. With moving images you are almost always working with a number of people in the production, and all of these people play a big role in how the final product turns out.

How does telling a story differ when using stills or moving images?

Telling a story is very different between both mediums. Obviously, moving images are used in groups and are usually accompanied by dialogue, sound and music to tell a story. Whereas a still image has to stand on its own and really comes down to how deep a viewer looks into the image and how they interpret it. That being said, it’s still important to create moving images with as much meaning as possible so they match/suit the overall mood and story you are trying to tell. Both have their challenges but in a way I would say it’s almost more difficult to tell a story with a still image as opposed to a moving image. I enjoy the fact that both have their own unique challenges.

Who do you think we should feature as our next photographer?

If I had to suggest someone I’d say my good friend Greg Russell as his images and writing posses a lot of depth and are always a source of inspiration.

Thanks Kyle! You can see more of Kyle's work at his website kylemcdougallphoto.com

Endframe

I must say, sitting at my desk at work completely absorbed in some unmemorable task, it was a welcome diversion to hear my mobile go ping and then see a message from Tim pop up on the screen. With the message saying ‘favourite image’, my concentration was immediately broken and interest piqued sufficiently to want to see what little morsel of information he was about to divulge. On this occasion though, not information about a great little book he had discovered or someone’s work but, an ask; ‘we’re starting a new feature in On Landscape..... pick a photograph to talk about… could be from a book or website or from a colleague’. Should not be a problem I thought to myself, duly agreed and turned my attention back to said unmemorable task.

Issue 73 PDF

You can download the PDF by following the link below. The PDF can be viewed using Adobe Acrobat or by using an application such as Goodreader for the iPad.

On Creativity – Pt 2

In part one of this article I looked at the psychological processes that underlie creativity and introduced the notion of flow. I tried to make it clear that creativity is an everyday part of human existence and not exclusively the domain of ‘gifted’ individuals. I don’t pretend to be an expert but it seems plain to me that humans have developed creativity because it has an evolutionary benefit. As history has repeatedly shown, creative leaps of the imagination can lead us to solve what had previously seemed ‘insoluble’. These solutions can lead to better living conditions for individual humans and the species as a whole – though, sadly, not always for the benefit of our neighbours on Earth. Creativity is not limited to artists, it’s a fundamental aspect of human psychology and appears in all walks of life. Scientists and artists – who appear on the surface to have very little in common – share the common tool of creative thought, though they differ in intent. There isn’t a single aspect of human existence that hasn’t at some stage benefited from a little creative thought. The scientists and inventors use it to gain practical advantages but artists use it to enrich our lives in less palpable but nevertheless equally positive ways.

In this article I want to explore how we might more easily access the heightened state of creativity that comes through flow. Flow is something that we are all capable of through concentrated application. By concentrated I do not mean the kind of furrowed brow, pained expression that might have the caption ‘Thinking!’ appended to it, but rather a calm exclusion of irrelevances - a state oddly more akin to peaceful daydreaming.

Many photographers, as well as other artists, have described this heightened state of awareness. The American photographer, Minor White, equated the preferable state of mind to that of an unexposed piece of film, static and seemingly inert yet pregnant with possibilities, ‘so sensitive that a fraction of a second’s exposure conceives a life in it.’ In an unconscious nod to notions of divergent thought, he suggested that any image might feasibly be formed upon the film (or sensor) and we should be ready to equally accept what passes in front of our eyes, not blinkered by convention or expectation.

Before I describe how we might achieve this I want to write a little about the importance of practice.

Just taking photographs is one way to get into the flow. Over many years I have witnessed Joe Cornish do just that. When arriving at a location new to him, he will spend some time studying his surroundings then start making images. This is a process I call sketching. Each image forms a part of directed play - and may also be a stepping-stone to flow. But I think it’s important to point out that Joe is a master craftsman. For him, the camera is no longer something that stands between his mind and an image, it has simply become the conduit for the image he imagines. Whereas, for less practiced individuals, operating the camera can interrupt the acquisition of flow. This is because self-reflective thinking ("What aperture do I need?", "Where am I focused?", "I need to stop down!", or any one of a hundred other questions…) can inhibit us from entering flow. Once in the flow these questions become part of the focused task.

But we need to enter it first.

I think that there’s a universal problem here. Let me explain it by contrasting Joe’s ease with a DSLR with my unease. When I use rigid bodied DSLR cameras I find it much harder to enter flow. For me, there are two obvious reasons:

Because I’m not as familiar with DSLRs as with a view camera; manipulating them involves tasks I’m not used to such as navigating a menu tree – I have to consciously think how to do things!

And because the ritual I’m familiar with is absent (more about this in a moment).

Both are different aspects of my unfamiliarity with the camera. They are only difficulties because I almost exclusively use a view camera. Joe can enter the flow through making images with a DSLR because he is practiced. And practice is the key!

He uses his cameras (of whatever format) many times a week and sometimes many times a day for weeks on end. Most of us don’t practice that much. If you wanted to play a violin concerto wouldn’t you expect to have to practice every day? Yet we get frustrated when we can’t make good images on the day we pick up a camera for the first time in weeks. If you want to enter flow easily the camera must not be something that you have to puzzle over, you need to be completely familiar and at ease with it. And that takes practice. Rather than thinking of photography as something you do on a special occasion, think of it as something that is an everyday part of your life. Once a day, pick up the camera and play with it. Think of this as practicing your scales. You’re not trying to produce a virtuoso performance, you’re trying to hone your skills and make the camera an extension of your mind’s eye. You don’t have to be in a special photographic place, a hallowed location, to do this. You can do this anywhere, even in your kitchen.

Dos and don’ts…

As I mentioned earlier, it’s hard to exclude everyday irrelevances from our minds when we make photographs. I know that they often crowd in and disrupt my ability to enter the flow state. After many years of trying to find an easier way into flow, I have come up with three guiding principles, one prescription and two proscriptions. Let’s start with the ‘do’.

Develop a ritual…

Flow and meditation are closely allied states - indeed, being in creative flow has the same psychological benefit as meditation with the added bonus that you’re doing something creative. In Zen, and other meditative practices, rituals are often prescribed as a means to enter a meditation. So, it’s perhaps no surprise that rituals also work for entering the flow. Don’t worry, I’m not suggesting that you sit cross-legged and chant before making a photograph. The ritual can be something very simple, informal and undemonstrative. And it needn’t be long. The ritual bouncing of the ball by a tennis player before they serve is a good example. Sometimes they do it twice, then serve. But sometimes you see them hesitate and start the ritual again. It’s not because the ball bounced badly – that’s got nothing to do with the serve - they’re simply waiting until they’re mentally and physically settled.

Some photographers already have unconscious rituals that they go through when making a photograph. This might be something as straightforward as going for a walk in the landscape, or plugging in their headphones and listening to music on an iPod (although I confess that music makes it impossible for me to concentrate on making an image), or just sitting and staring. It’s not a fail-safe approach, but associating some simple task with making photographs can help you to enter the flow. You might try viewing your surroundings through a framing device such as a 35mm slide mount or piece of card cut in the appropriate proportions.

I consider myself lucky that working with a view camera involves working through a prescribed, ordered set of tasks; unfolding the camera, setting it on the tripod, donning the darkcloth, using the focusing loupe, opening the aperture and shutter, applying movements and working through the iterative process of focusing. These amount to a formal ritual. As I step through the process I can feel my visual perceptiveness increase as I relax into a ‘photographic’ frame of mind. I think that the darkcloth is a particularly important part of the ritual as it excludes irrelevant visual information. Under the hood, I am only aware of the image on the ground glass, the surrounding visual context is lost to me. I operate the camera by touch, as musicians do with their instruments. I feel the positions of the camera. There are no distracting menus to scroll through to pick settings, no text to read and process with my conscious mind. I find that I can let my subconscious dominate.

Don’t rush…

Many people seem to feel that they have to make a photo NOW! But placing a time pressure on yourself is almost guaranteed to keep you out of the flow. On photo tours and workshops, the pressure sometimes comes because this might be the only opportunity someone gets to make an image at a particular place. I sympathise with this desire to come back from the hunt with a prize but know that rushing isn’t the way to get first prize.

Of course, the light and the landscape also exert a time pressure: we look out and notice that a cloud will be in just the right position in a few moments and rush to capture it; we see that the sun will soon set and rush to make an image; we see the light flowing across a mountainside and - realising that rain will soon be upon us – rush to pick up the camera… As a wise Yorkshire woman recently said to me, "Dear me, we’re all of a gallop!" It’s very hard not to react to these external pressures but experience has taught me that my images are better if I can resist the temptation.

One participant’s tongue in cheek feedback from my webinar in February was, "I now know that wandering randomly around is a key technique I need to master." That’s frequently what I do, so he’s actually perfectly correct! People sometimes ask me if I feel that I’m missing out on images, by only making a handful a day on the 5x4 as opposed to their tens or even hundreds of frames? The answer is no, I don’t. I decided long ago that I’d rather make fewer images but try to make them count.

Once I’ve found a subject that excites me, I often walk around it for ten or fifteen minutes before I pick up a camera. In that period I’m tuning out of any irrelevances and tuning in to the subject. Minor White suggested that, ‘If you could stop the shouting of your own thoughts in your ears, you might be able to hear the small voice of . . . a pine cone in the sun.’

If you’re struggling to see images, I recommend that you just sit and "be" for a while. Quietly contemplating your surroundings gives you time to really look at your environment, time to lose yourself and connect with its ambience. I strongly believe that time spent just sitting in these circumstances isn’t wasted; in fact it’s often the most productive thing you can do and will pay huge dividends.

Stay calm…

Don’t expect too much of yourself. This might seem like an odd thing to suggest; surely we’re constantly striving to make the best image that we can? Yes, but that doesn’t mean that we should expect to make a masterpiece on any one day or even once a month or once a year. Performance anxiety, setting your sights too high, is bound to exclude you from the flow. Your best work will almost certainly come unexpectedly. Always try and enjoy making a photograph for the simple pleasure it brings.

Another kind of anxiety arises from simply being in an amazing location, well known for its photographic potential. I’ve sometimes noticed participants on workshops being disappointed in the most incredible landscapes. This disappointment can blind them to possibilities and exclude them from the flow. Yosemite Valley, in California, is a perfect example. We all know Ansel Adams’ famous image, "Clearing Winter Storm’. It’s an incredible photograph of an epic moment. We should remember, however, that Adams lived and worked in Yosemite for seven decades and only made one image with such spectacular conditions. It’s completely unreasonable to think that we will find anything like that during a ten day visit. OK, it’s the Gates of the Valley at Yosemite – the landscape photographer’s Mecca! But it’s really just another place to find an image. We should treat all locations equally. Each is a place where we might make a good image. But there’s never any guarantee that we will. If we’re too in awe of a famous place we won’t be able to enter flow.

On any one day, your ambition should simply be to make an image to the best of your abilities. And it really doesn’t matter if you don’t make an image. Just being out and looking is part of the ongoing process of developing your aesthetic sense.

Anxiety can also arise from comparing ourselves to our peers or the photographic greats. It’s pointless even to think in terms of a league table. Art has no absolute points of comparison, only subjective ones. Comparing your work on a particular day to someone else’s - or even to earlier work of your own - is only going to make you feel anxious and unproductive. Both these feelings are enemies of the flow. Just try and be calm. Forget the past and ignore the future. Focus on now. In a sense, we are never more completely in the here and now than when we are in the flow. By ignoring irrelevances we allow ourselves to concentrate all our attention on the present.

In conclusion…

Flow was something that happened in my creative life long before I comprehended its significance. Twenty years ago I thought that it was just an odd state that happened from time to time. I couldn’t predict when it would happen but I knew that afterwards I would feel energised and fulfilled. Talking to other photographers, I realised that they too had experienced it. Like me, they found that flow often accompanied periods when they made what they considered to be their best work.

Of course, I’m not successful all the time. It’s not often acknowledged but our mental state is more important than anything else when we’re trying to find photographs. Mental barriers of one kind or another often make it hard to see images and impossible to get in the flow. Apathy, for instance, is quite a common barrier for me.