For many years I have collected books of photographic images. I love them. And all those years my photography has been centred around me as a print-maker. But the walls and clamshell boxes fill up and the occasional exhibition, sale or gift of some treasured print did little to stem the burgeoning inventory.

And then about five years ago I read an article by Brooks Jensen the editor and publisher of the wonderful Lenswork magazine. This introduced me to the world of handmade artist’s books with beautiful papers and bindings that were a lovely way of presenting your images. He particularly championed the concept of simply bound ‘Chapbooks’ which are just a few pages long.

And digital printing is ideally suited to the medium of a one-off book. The quality of a well-crafted digital inkjet print will easily surpass almost all commercially printed books. The paper choices, especially if you stray from the usually coated inkjet papers, are myriad and delightful. Any photographer with some persistence and a few tools can turn a collection of their images into a crafted original artefact.

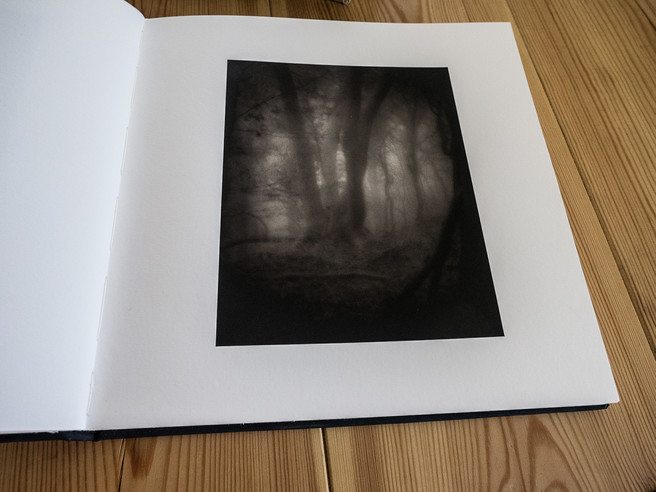

A year or so later I did an awesome digital negative and platinum printing workshop with David Chow at his home. This brilliant and generous teacher, who sadly died far too young, showed me his collection of handmade books by 21st Editions of New England. I particularly remember the exquisite Sally Mann book of beautiful bound original platinum prints that took my breath away. And perhaps it should as these editions sell upwards of $15,000 a time.

But we all know what the feeling is like when we view something we perceive as perfection. We know we never could achieve that standard, but we know it exists and that it can be done and it will forever form the aspiration and benchmark of our own work.

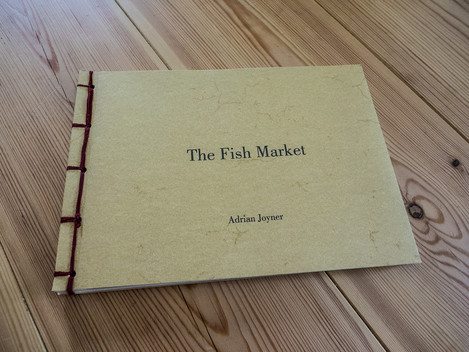

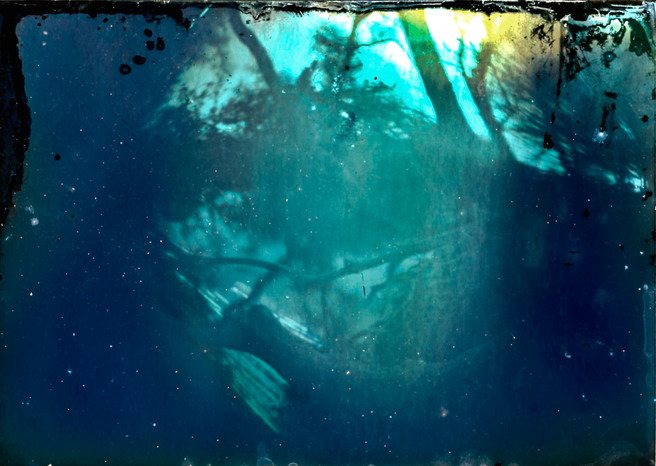

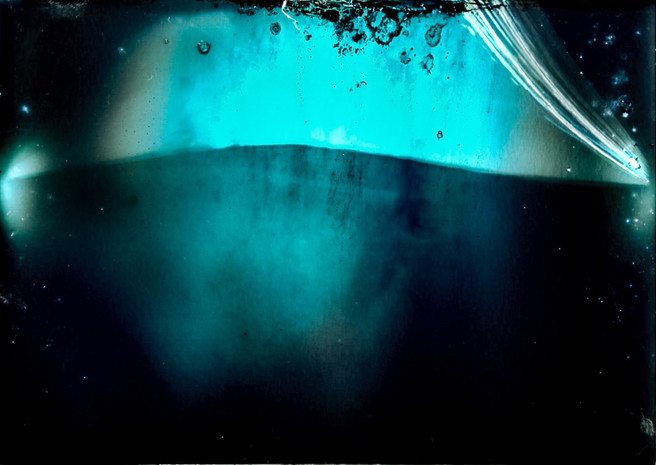

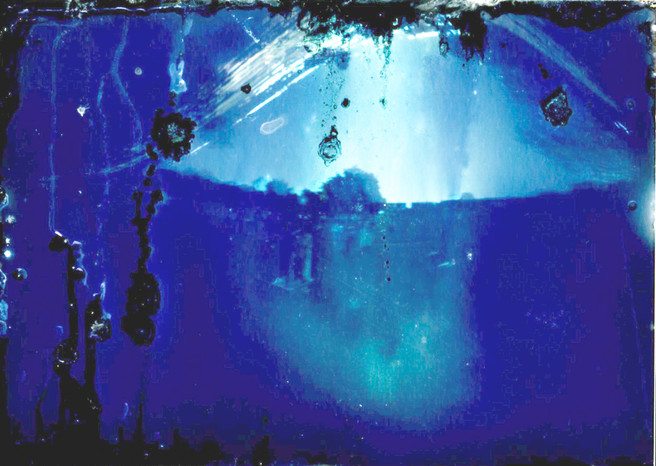

Handbound artist books now represent most of my photographic output. I think I am confident their legacy will be longer for my heirs than any of my stored boxes of prints, whilst taking up a lot less room and being immensely satisfying to produce. I like the idea that the images have to stand as a cohesive whole and not just a collection of ‘greatest hits’. I like the idea that they must be considered and sequenced. In binding a book with its oft considerable cost and labour you are making a statement that you do approve of the images and that they are finished – it helps to subdue the ever-present self-doubt. I like the feeling of working without an undo button where a careless mistake at the bookmaking process can wreck all your expensive work so far – just like it was in the darkroom days.

As well as sharing my experience with making one-off artist books I will also give some suggestions as to how you may have smallish quantities of books commercially printed for exhibitions, publicity or for sale. It is quite possible to economically self-publish a book of your images – you just must find a way to harness your social media and other resources to market and distribute them.

The Design of the Book

The basic structure of the book is dependent on the number of images, your bookbinding skill, the tools available and your personal taste. The number of ways of designing and constructing a book is endless and a short article like this will always be inadequate as instructional material. I can only advise that you buy a couple of books about bookbinding among the hundreds available from your local bookseller or Amazon and start reading and practising. As a start, I can recommend ‘Bookbinding – A step by step guide’ by Kathy Abbot.

And, of course, the internet is your friend as a treasure trove of instructional material and inspiration.

A short workshop at a local bookbinder or art college will be an invaluable help but ultimately the only way to learn is to start making some simple books yourself.

Some styles that I have used are as follows;

Accordion or Concertina Book

One of the simplest forms of book construction consisting of a continuous folded sheet of paper folded back and forth in page widths which is often pasted into a cover.

Stab-Binding

This Japanese method of making books is an excellent place to start. The book is a stack of single unfolded sheets and is simple to make and bind an elegant book.

Single Section Bindings

This would comprise a single set of folded papers sewn together to form a book block. It would often have a cover that would be bound to the section separately.

Multi-section Bindings

As the number of pages gets larger most books will then necessitate the use of two or more sections that must be sewn together. This also would usually have a hardcover bound to the book block.

Book Materials

A huge variety of paper and board using in the construction of a book is available from sources like Shepherds or Ratchfords. When printing photographic images, the obvious choice would be the increasing number of double-sided inkjet papers available. These papers can be expensive so I can recommend the Fotospeed Duo papers, the very economical Bockingford Inkjet Watercolour paper and Ilford Premium Matt Duo as good value reliable starters. Many of the Japanese inkjet Awagami papers are also double-sided.

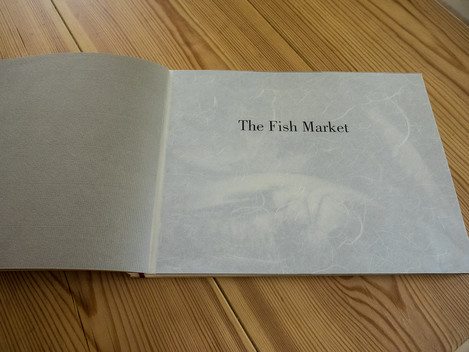

Non-inkjet coated papers can, of course, be used to beautiful effect but with the inevitable loss of contrast. Some wonderful old and rare book papers which inkjet print well are available from www.vintagepaper.co as well as lots of other bookmaking supplies.

ICC profiles for printing are available for the coated papers but if you have the facilities you may wish to produce your own for the uncoated papers. Especially with these, it is important that you pay attention to soft-proofing, micro-contrast and sharpening to get the best output.

An early introduction to papers from any bookbinding instructional will stress the importance of the correct grain direction of the paper. For the pages of the book block, this should be ‘short’ and in the same direction as the fold. Almost all inkjet double-sided inkjet paper apart from some expensive Hahnemule paper seems to be long grain. I know it is supposed to be critical by I’ve never had any real problems with the use of long grain paper.

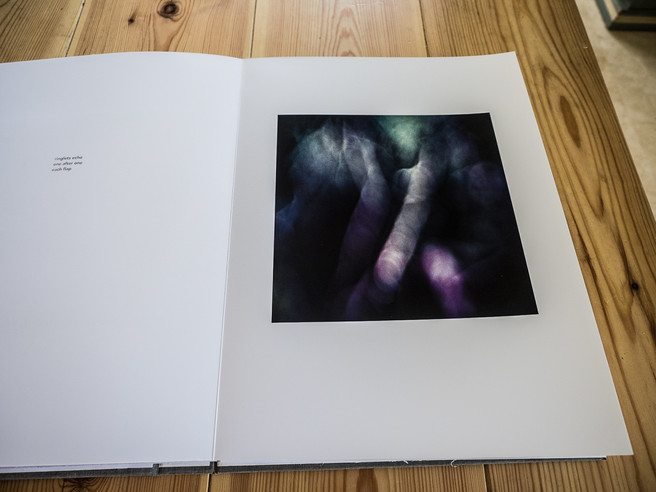

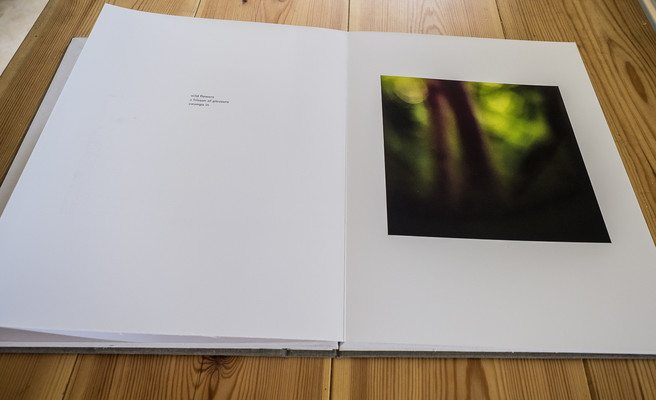

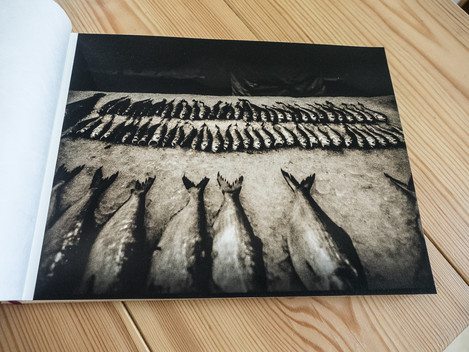

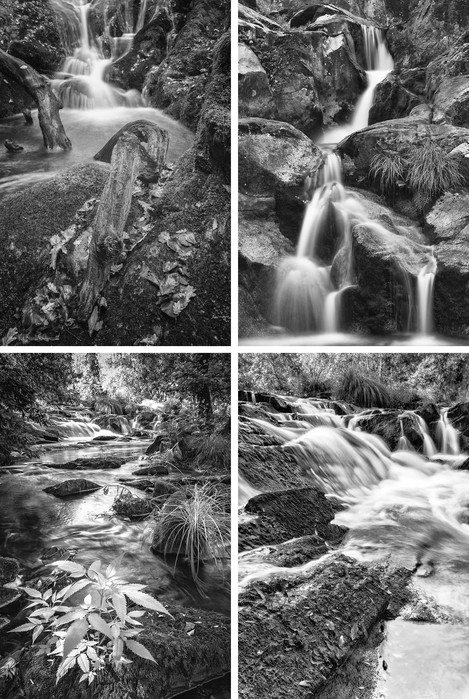

Sequencing your images

The photographs you want to include in the book are a personal choice and the reason why you want to make the book. It’s good if they have a strong compelling concept or ‘tell a story’ with or without additional text. In the end, it’s your call.

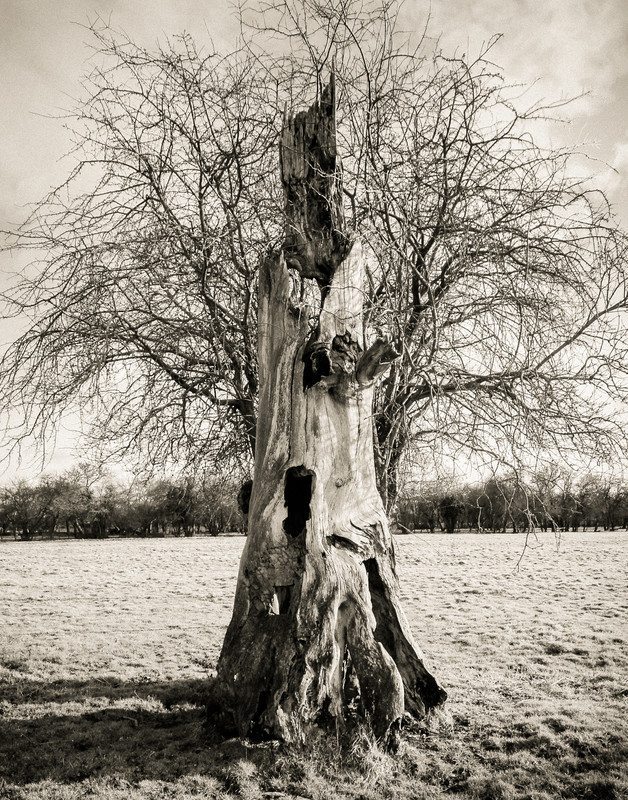

I fully admit that when I started I was very bad at sequencing my images. I’d read that it was the most important decision about a book but I just couldn’t get it. My early books didn’t really have any sequencing whatsoever and it certainly showed. A workshop with a couple of handmade book greats John Blakemore and Joseph Wright made things a lot clearer.

I usually make some small prints of all the eligible images, lay them out on a table and commence the culling and shuffling. If you feel comfortable without printed copies then Adobe Lightroom in ‘Survey’ mode on a collection will allow you to do the same on the computer screen.

A resource by Nicole Andermatt on her website is a really good read to start understanding sequencing techniques and options.

Her good advice is ‘Pay attention to beginning and end; visual and content related gaps, patterns, irregularities, shifts; paper quality, book and image size (why this size, why not smaller, bigger?), amount of images, text, typeface. Analyse things to death.’

Page Layout and Design

The software that you need for the layout of the pages prior to inkjet printing will ultimately depend on the size and complexity of your book design and the depth of your pocket.

I use Adobe InDesign for all my page layout requirements. It does have a bit of a learning curve but ultimately simplifies the complexities of building a multi-page book considerably. Unfortunately, it is now only available as part of an expensive Adobe Creative Cloud subscription. Older versions which claim to be legal de-activated software are often available on eBay. You certainly do not need to use the latest release of InDesign for a book layout. For simple books then Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Elements, Microsoft Word or Microsoft Publisher would be adequate.

An excellent step-by-step guide to designing and typesetting your book using Adobe InDesign is ‘Book Design made Simple’ by Fiona Raven and Glenna Collett. Although much of its content is about text rather than images it is a valuable resource as it specifically concentrates on book layout.

A pair of sequential facing pages is called a layout spread. For multi-section books, you will have to tackle the complexity of ‘imposition’ which is the process of creating printer spreads from layout spreads. For example, if you are editing an 8-page book the pages will be in sequential order in your layout program. However, when you print the two pages together on the single sheet of unfolded paper or ‘spread’ page 2 will be positioned next to page 7 so that when the paper is folded and collated the pages end up in the appropriate order. Commercial and free software is available to considerably ease this process of producing a printable printer spread in pdf format - Google ‘Indesign imposition’. This pdf can then be directly printed or exported as an image file as you wish.

Printing and Assembly

The equipment needed for the construction of a book will depend on its design and complexity. If you want to make a book that resembles a traditional high quality commercially produced book then it is likely that you will need to make a greater investment than that needed for a more handmade look.

A simple few page concertina design can be printed and folded in a very short while with not much more than a Stanley knife and a bone folder. A hardbound multi-section book may take a week and involve a sewing frame and various presses. I strongly advise that if you want to make professional looking books that have many pages that you invest in a book-makers plough and press to cut the assembled book block pages squarely to size. I ruined quite a few books in trying to do this with a knife and straight edge. I recommend www.bookbinding-supplies.co.uk who make and sell well made and reasonably priced ploughs and presses.

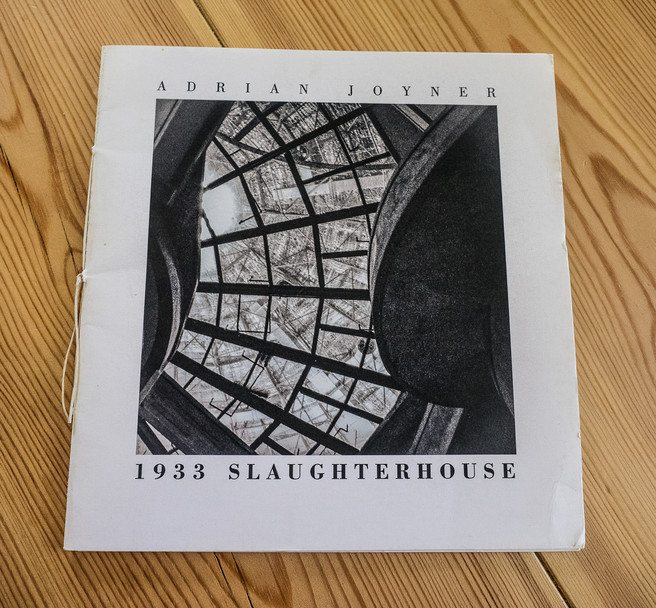

Commercially Printed Books

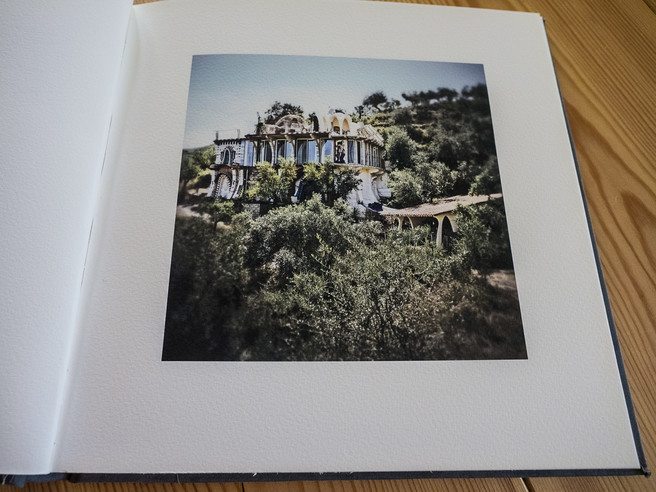

If you have a need for more than a copy or two there is clearly a problem in printing and making the books completely by hand, especially if it has a large number of pages. I have printed books through various well known on-demand printers such as Blurb but I was usually unimpressed by the quality of the printing and the considerable cost hardly made it financially viable despite their endless 40% sale offers. It is very easy to end up with a book costing £50-£100 which makes it prohibitive to sell or give away.

After some research, I had some small run (10+) books printed by an on-demand print service offered by www.mixam.co.uk and I was impressed. Their choice of styles is much more limited than, say, Blurb and there is no online software to layout the book – you must provide a pdf to a professional standard of the formatted book pages. I find that is no hardship as I can then design the book in Adobe InDesign as I want it rather than to try to adapt to a Blurb packaged style. They are exceptionally helpful in reviewing your pdf and helping you to correct any mistakes that would affect the printing. They do have a wide range of paper types, surface finishes and weights. I think that the ‘natural’ paper is particularly attractive.

Moreover, and I would hasten to mention that I have absolutely no connection with Mixam other than as a very small occasional customer, their customer service is exceptional and very helpful. But I have no doubt that if you wish you will be able to find alternative printers with similar capabilities.

Although inferior to a fine ink-jet print, in my experience the quality and consistency of their printing noticeably surpass that received from Blurb and other similar print services. Additionally, I have purchased many portfolio photography books from the likes of small digital publishers such as the sadly demised Triplekite and have often also been disappointed by the quality of the image print reproduction especially for the lower cost editions.

I suggest you purchase one or two books from Mixam with a few of your images printed on your chosen paper type. You can then experiment with your colour-proofing (you will be expected to supply images in CMYK format), image sharpening and micro-contrast parameters. Having found the image preparation settings that work best my experience is that Mixam will make very consistent and repeatable print runs – which is not always true of all on-demand printers.

The costs are remarkably good. An A4 perfect bound (glued) book in portrait format with a hundred pages and a thick softcover using the highest quality papers would be less than £10 each for a quantity of ten. Larger quantities, fewer pages and smaller sizes reduce in price accordingly. Even one could be purchased for less than £25 which is a very good way of making a proof copy before committing to a longer run.

The economical larger scale production of a well-printed book opens many opportunities. You could self-publish a book and sell it to your friends and followers through your website. You won’t need to commit yourself to a large print run and you can re-order more copies with a few days turn-around. You could become an Amazon seller with a basic account and link that to your website and social media. For inspiration just look at the delightful 55 series of little photography artists portfolio books produced by Phaidon. If you expect to sell many different books and want to look professional you can buy ten ISBN numbers for £150.

Although printing through someone like Mixam does involve some restrictions on book sizes and styles this can with some ingenuity be turned to your advantage. For instance, you could buy say ten or a hundred copies of a soft-bound book in A4 portrait format but with the pages formatted as for landscape mode, accurately cut off the spine using your book-binding plough and rebind the book landscape with an inkjet printed cover on some exotic paper with elegant Japanese stab binding. You could add some additional pages in different papers such as vellum, handmade or Awagami Japanese inkjet papers for an alternative artistic and creative effect. You could keep the book blocks as they are but just bind them into a different cover. You could make a slipcase to hold the book and perhaps include an original inkjet print. There are many possibilities depending on how much you want to differentiate with a little customisation the book from a mass-produced book into a bespoke artefact with added value.

I hope that this little article will inspire you to investigate making artists books of your photographs yourself either as one-off hand-crafted unique artefacts or self-publishing for a wider audience. If I can be of any further help you may contact me through the contact page on my website.