Over a year ago now we carried out various tests of medium format digital camera systems and film camera systems. The results, whilst interesting, didn’t tell us a whole lot about 35mm digital camera systems. Just after the D800 and D800E came out we followed these up with a comparison of these cameras, which are still the gold standard for 35mm sensors, and medium format film. With the surge of interest in film we thought it would be good to share the results with a wider audience.

If you've come here from Petapixel - you can read a longer version of the article that appeared there on this page or you can take a look at the original Big Camera Comparison we ran by clicking here. Thanks for visiting!

How to Compare

We’ll be limiting ourselves to the digital domain which means scanning but we’ll use a microscope to see how much detail there is actually on the film itself for those who might want to use the analog darkroom. Here are the possible ways to compare.

- count lines - should give us the absolute peak resolution of the film files.

- compare results on screen - good for pixel peepers

- compare prints and projected pictures - actually gives useful information for the photographer

Counting Lines

We photographed a test scene with various cameras, ensuring focal lengths were very similar and adjusting distance to target where there was a small discrepancy. Where aspect ratios were different we kept the short edge angle of view consistent. As we have a landscape bias, all of the lenses were chosen to be approx 24mm full frame equivalent. (Zeiss Distagon 25mm f/2 and Mamiya 7 50mm) Here’s a photograph of our test setup.

The test sertup as a resolution chart, a couple of very sharp 5x4 transparencies and a few ‘real world’ items (well - real world for photography geeks anyway!)

We used the number of lines we could perceive (regardless of contrast) to calculate number of line pairs per picture height (i.e. half the vertical pixel count). From this we could work out a megapixel equivalent.

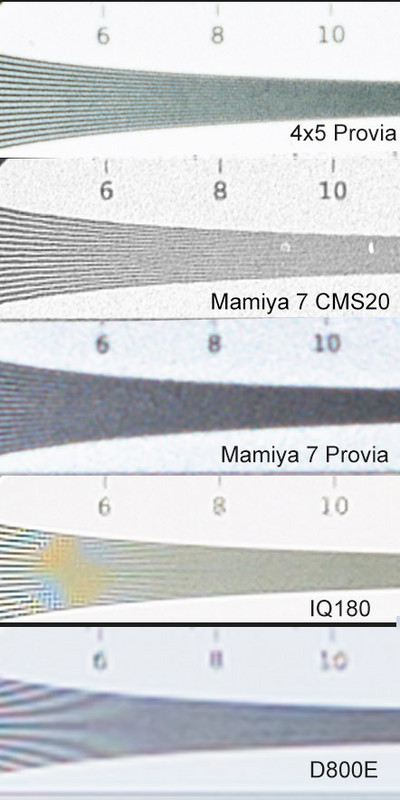

Here’s a sample of resolution scale from a few of the scans we used. These scans were from the Howtek 4500 drum scanner (colour slide) and the Screen Cezanne flatbed (black and white)

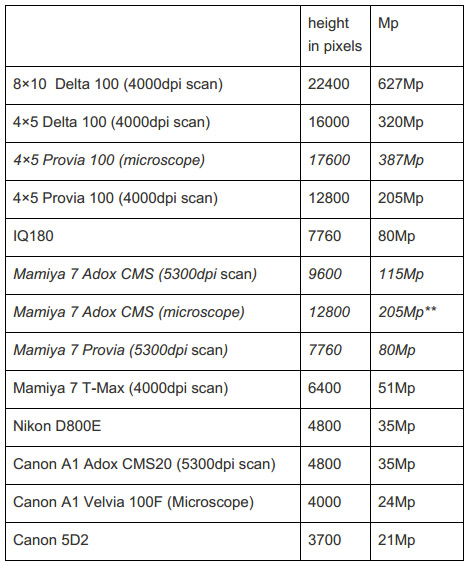

And here are some of the calculated stats…

** beyond resolution of chart.

The IQ180 and the D800E produced the full resolution of the sensor at very high contrast and hence they managed to get the theoretical maximum resolution from their sensors.

The surprising thing here is just how big those results are from the medium and large format cameras! (That should get the trolls out in force!).

These figures are supported by our colleague Henning Serger who has been making extensive tests of real world film and sensor resolution for the past few years. His figures show colour film with up to 135 line pairs per mm, B&W film up to 150 lppmm and finally microfiche films such as Adox CMS20 at up to 260 lppmm!! In his scientific tests the object contrast of the test pattern is 1:4 (two stops). For the comparison tests a Nikon Nikkor 1,8/50 AI-S and a Zeiss Makro-Planar 2/50 ZF are used at f5,6. In this test with both lenses the D800 reached 80-85 lppmm, and the D800E 90-95 lppmm. (at a 1:64 contrast Zeiss measured colour film at up to 170lpmm, black and white at up to 180lpmm and CMS20 at 400lpmm!)

Here is a list of equivalent megapixels for each line pair figure.

90lpmm = 28mp

100lpmm = 35mp

120lpmm = 50mp

140lpmm = 68mp

260lpmm = 235mp!!

This is the data actually on the film (Henning uses a projector too - you still have to get this either enlarged or scanned in and that always loses some resolution. The maximum optical scanning resolution of any scanner I’ve tested is just under 6000dpi and my best scanner peaks at 5300dpi. This gives a maximum possible digital camera equivalent of 38mp. If your scanner peaks at 3500 to 4000dpi (as many do) your maximum equivalent is 19mp to 21mp.

Interestingly this seems to be the sorts of figures that you get bandied about in the ‘better’ forums discussions of the resolution of 35mm film.

If you’re interested in medium format cameras, Henning’s results suggest that you can get within 10% of the figures for 35mm cameras using good lenses (i.e. The Mamiya 7 or Hasselblad lenses). This gives up to 125lpmm for colour slide film and for Adox CMS you can get up to 210lpmm. If you were to work out the resolution on 6x7 film you would get the following

90lpmm = 136mp

100lpmm = 168mp

120lpmm = 242mp

140lpmm = 330mp

210lpmm = 741mp!!

Henning also tested the scanned results using an ICG 370HS and an Imacon X5 and found colour film to have up to 100lpmm and Adox CMS20 up to 130lpmm. Using a Nikon Coolscan colour slide film acheived up to 60lpmm and Adox CMS20 up to 65lpmm. Henning has also tested slide projectors and has acheived up to 125lpmm - so where 4K is about 8Mp, 35mm projected slides can achieve 50-150Mp (more information in a future article).

CAN WE TRUST THE NUMBERS?

Well it turns out that numbers don’t tell the whole story (when do they ever!). Despite being verified by myself and others, the fact that the digital camera give their finest detail at very high contrast and the film cameras give their finest detail at about <10% contrast means that comparisons using numbers don’t accurately affect the perceived image quality.

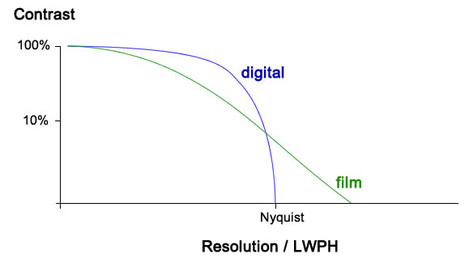

The graph of the contrast of line pairs against resolution for film vs digital will look something like this..

This is just an illustrative graph to show the idea that digital doesn’t lose contrast in the way that film does. In addition digital can cope with a lot more sharpening because the files are so clean whereas film loses contrast with increased resolution and sharpening is quite often limited by grain. However when digital does lose contrast it drops off dramatically while film is still giving some detail, albeit at lower contrast.

So although on paper it looks like 35mm film should keep up with modern 35mm digital and medium format film should blow 35mm digital away, the actual real world results are somewhat less amazing but still pretty impressive.

COMPARING ON SCREEN

So let’s take a look at the D800E compared with Mamiya 7 using Velvia 50 film and Adox CMS 20 to see just how these figures translate into photographs. First of all here's the test area again (slightly different than above).

Well I think we can see that the Mamiya 7 in colour is just exceeding the D800E in terms of detail and the CMS20 is substantially better. Normal fine grained black and white film would be somewhere in between (i.e. Delta 100 or T-Max)

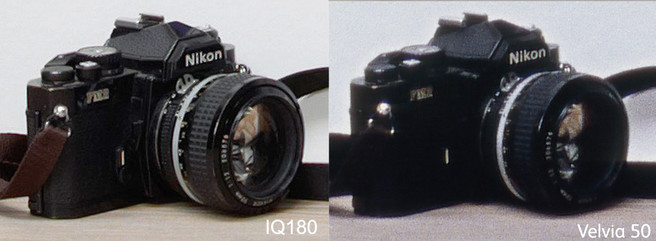

Let’s see how well the Mamiya 7 results compare with the IQ180 just to see where they fit in the megapixel race…

This shows that although comparing fine detail shows a fairly close match between the two, in actual fact the IQ180 looks a lot cleaner and sharper. This is a result of the high contrast edges in digital. The Velvia 50 shot is suffering a bit because of underexposure - the dynamic range of the IQ180 blows the transparency film away (the photographs were exposed for the highlights on the lightbox). However the detail on the Velvia shot isn’t doing too badly - small details like the markings on the lens look good but overall the clean, high contrast detail of the IQ180 makes the photograph look clearer.

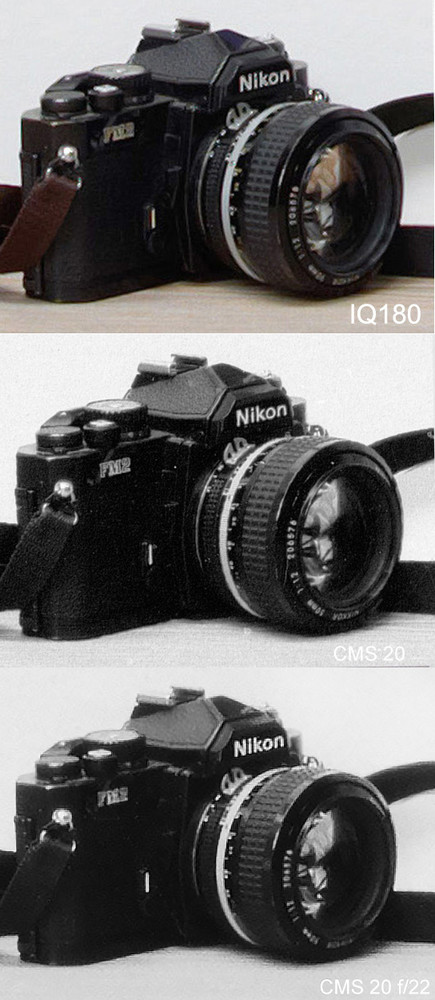

Here’s another comparison showing the difference between an IQ180 and the Mamiya 7 but this time using Adox CMS 20 film. The Mamiya result blows away the IQ180 in this case and is still a fairly close match even at f/22. This goes to show just how good old lenses actually are (especially the Mamiya rangefinder ones) and on a sideline proves that f/22 isn’t the hellhole that many photographers believe it is (for more about that refer to Roger Cicala’s article about diffraction - http://www.lensrentals.com/blog/2013/03/overcoming-my-fentekaphobia)

Well I think the thing we learned here is that the type of film makes a substantial difference. Adox CMS 20 has it’s own developer but can be stand developed in Rodinal - not something you can send to your local lab. However - one thing it does prove is that medium format lenses are quite capable and have a lot of leeway left for sensors to increase in resolution substantially.

WHAT ABOUT LARGE FORMAT?

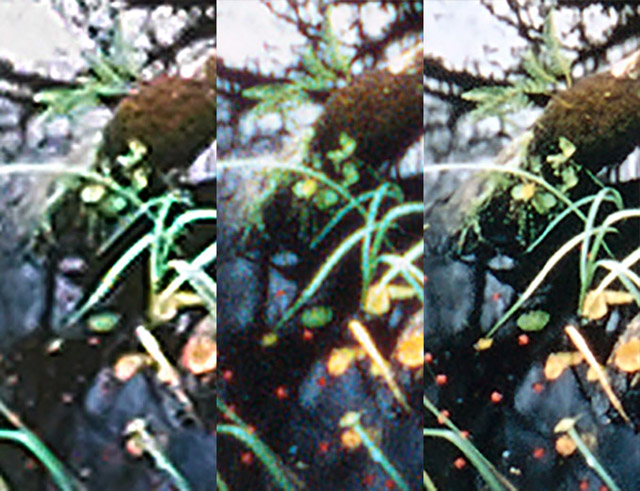

We looked at large format (4x5 & 8x10) shots in our previous tests so here are a final couple of comparisons between 4x5 and the IQ180. This first is a section from a transparency that was placed on a lightbox.

From left to right this is the IQ180, 4x5 Velvia and 8x10 Velvia.

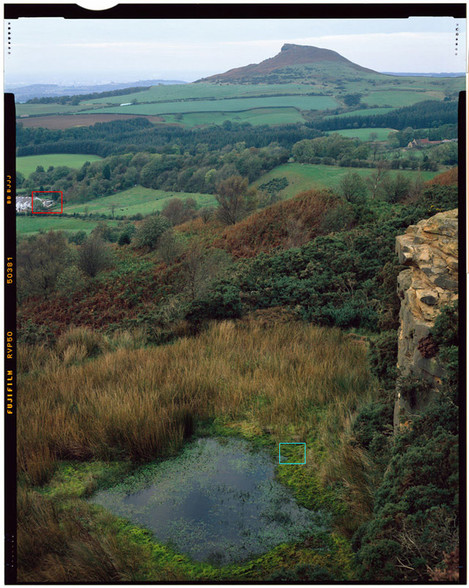

Finally, here’s the real world landscape photograph that we took. We’ll show a final couple of comparisons in the very bottom area marked in red and in the area on the left hand side of the screen.

First lets look at a comparison of the small village on the left hand side of the shot in the red square.

As you can see it’s a close call. Some things look more refined on the 4x5 Velvia (The garden chair, the car grille) and some things look a lot clearer on the IQ180 (the garage roof and walls). In a print of this section things were ranked pretty closely.

Why are the results from 4x5 not performing as well as indicated by the slide comparison? Well in the real world we had to stop down from our optimum aperture of f/11⅔ to about f/22. This reduced the max resolution of the 4x5 shots. The IQ180 needed stopping down too but that just reduced the contrast at the sensors maximum resolution and with a bit of sharpening it didn’t really do much damage.

WHAT ABOUT COLOUR?

One of the interesting things that cropped up was the way that the digital sensors deal with colour in terms of tonality and resolution. Because only one in four pixels are blue or red, quite often colour resolution is reduced in comparison with luminosity resolution. These look fine at small enlargements but when images are shown larger these artefacts can show through.

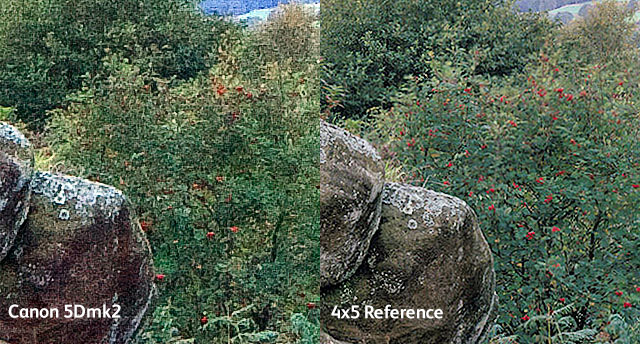

Here’s a great example of the problems with having only a few red pixels from an outing a few years ago, comparing a 5Dmk2 with 4x5 Velvia. Obviously the 4x5 Velvia has more resolution but we downsampled it to match the 5Dmk2 and got the following result (show at 200%)

On the left we can see all of the berries on the tree but on the right (the 5Dmk2 image) a lot of the berries have disappeared. The only berries shown are where there were larger groups of them (i.e. a single pixel size berry is unlikely to match up with a single red pixel whereas a group of berries covering 2x2 sensor pixels will definitely hit a red filtered one)

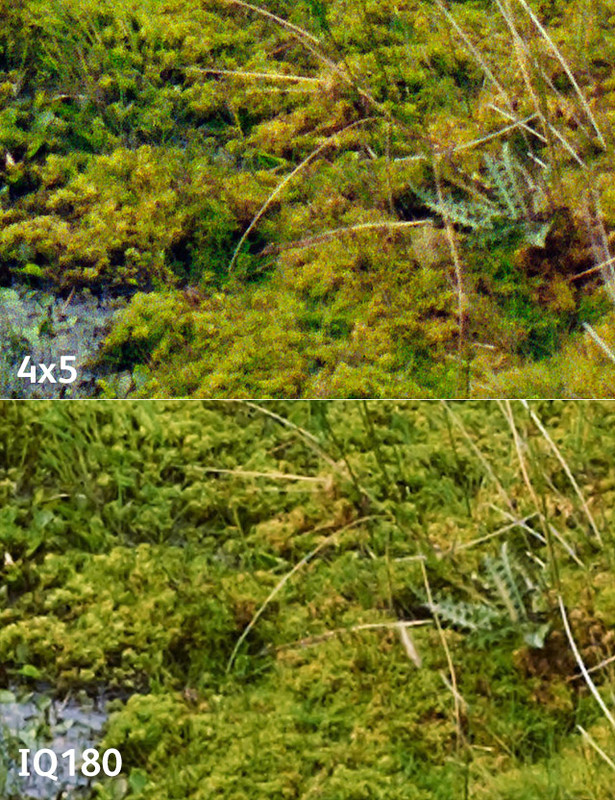

Also colour film still seems to differentiate colour differently to digital (depending on the camera). Here’s a sample of our test image from the cyan square at the bottom of the view next to the pond.

On top we have a 4x5 Portra 400 scan and on the bottom the IQ180. I think most people will agree that the 4x5 Portra 400 version has much clearer colour differentiation.

SO WHAT ABOUT 35mm FILM?

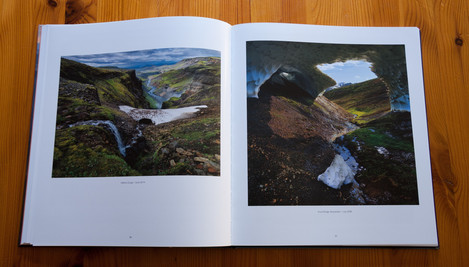

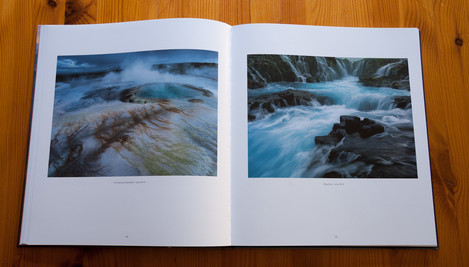

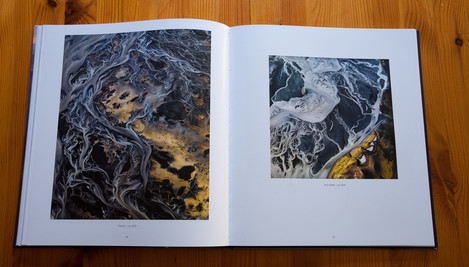

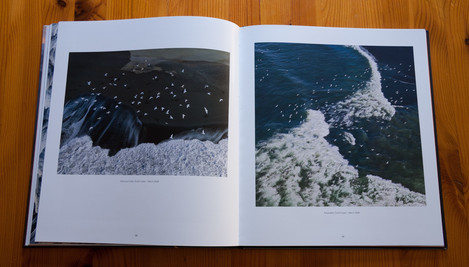

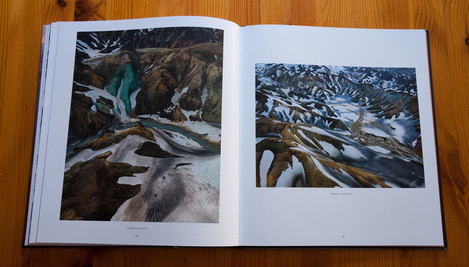

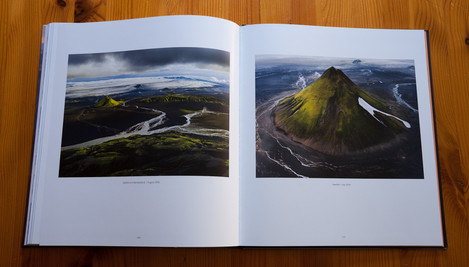

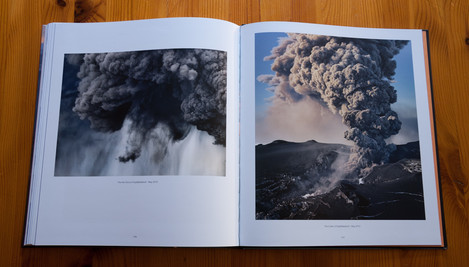

Well we didn’t include 35mm film in the test - it was originally aimed at comparing 10x8 film with the IQ180. However I had a recent scanning job for a colleague of mine who has taken 35mm film cameras to some of the highest mountains (Alan Hinkes - the UKs first mountaineer to climb the world’s 8000m peaks) in the world and he has allowed me to show a couple of these here include 100% crops. These photographs were taken using a Ricoh GR1 on Fuji or Kodak transparency film. These images make quite respectable 30” by 15” prints. (the first is Fujichrome and the second Kodachrome 64)

Here’s another

WHAT ABOUT PRINTS?

We made prints of our test charts at various sizes and also of the photograph taken outside in windy conditions and asked people to say which was better quality in terms of detail and sharpness. We asked a mix of photographers and non-photographers.

Interestingly quite often the digital camera photographs would perform better at smaller image sizes but once they reached about 200dpi then the film photographs were often chosen instead (this is true for some of the comparisons between the IQ180 and 4x5 and D800E vs Mamiya 7). From the comments made this was often to do with the ‘plasticky’ nature of digital images once they are enlarged beyond a certain size.

In general people ranked the 4x5 and IQ180 fairly closely, the 4x5 coming out top just a little more often.

They chose the Mamiya 7 files over the D800E files most of the time (although a small but significant number chose the D800E over the Mamiya 7 files - it seemed there was a large factor of flavour preference).

Effectively we saw the following hierarchy.

- 10x8 (a significant winner still)

- 4x5 Black and White

- 4x5 Slide and Colour Neg

- Mamiya 7 Adox CMS20

- IQ180 / Mamiya 7 Delta/T-Max 100

- Mamiya 7 Slide

- Mamiya 7 Colour Neg

- D800E

.. AND PROJECTION?

Well digital projection is definitely getting there with 4K and we’ve just run a conference where we used one of Canon’s high end HD (1080p) projectors on a 70ft high screen. The results were very nice indeed but we’re fascinated by Henning Serger’s results with film projection (both 35mm and medium format) so much so that we will be converting a couple of our presentations in next years conference into medium format slides using LVT film writers.

CONCLUSION

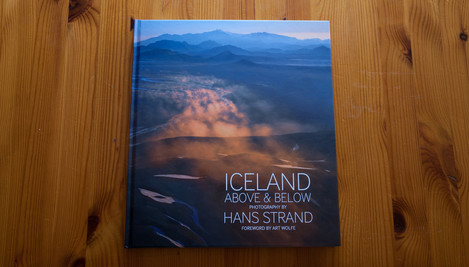

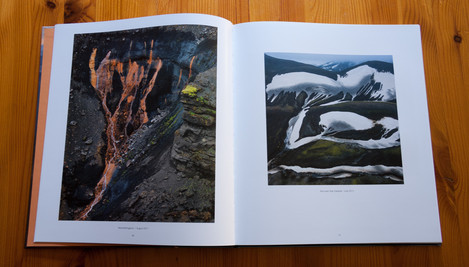

Comparing film and digital is a difficult task as they are not designed to record light in the same ways. However I hope this has shown that with the right scans medium format film can compete quite well with digital and even 35mm film can produce decent size prints (enough for book publishing definitely - see Alan Hinkes “8000m”, nearly all shot on a relatively cheap 35mm film camera (Book currently available from Amazon).

Some comments on the results though

- Medium format lenses can resolve impressive amounts of detail. More than enough to cope with digital sensors to increase in resolution at least four fold more more.

- 35mm lenses, even legacy ones (Henning Serger uses an old manual Nikon 50mm in addition to the modern Zeiss lens) still outresolve all digital sensors.

- 4x5 film competes very well with the best that medium format digital has to offer

- in projection, film delivers an outstanding, unsurpassed quality at extremely low costs (both 35mm and 120)

- optical printing of film is also an excellent quality option at very low costs.

SCANNING COSTS

Fortunately I run a drum scanning business so we had unlimited access to high end flatbeds and drum scanners. We scanned the film using various scanners from a cheap Howtek 4500 drum scanner, a Screen Cezanne Elite Pro flatbed, an Aztek Premiere, an ICG 380 and a Heidelberg Primescan D8200. Microscope measurements were also taken using a 80x stereo microscope.

People will obviously say “well that’s fine if you have a drum scanner! What about your average photographer”. Well the beauty of film is that you can send your film off for very high resolution scans at any point in time. For most purposes though something like a Nikon 8000 or a Minolta Dimage Multi-Pro will produce images that will match the best of 35mm digital (with the right camera and lens). An Epson V750 gets very good results with 4x5 and 8x10 (especially with negatives).

Even drum scanners are now affordable for the dedicated film photographer. I purchased my Heidelberg from Karl Hudson who refurbishes, delivers and gives a warranty for his scanners for less than the price of a top end DSLR.

Great enlargers can also be had at amazing prices and projectors that blow away 4K can be had for peanuts.

ISN’T THIS JUST A PRO FILM RANT?

Actually no, well maybe a little. For myself I happily use film and digital and am just about to invest in a Sony mirrorless camera that I will use alongside my 4x5 and 10x8 cameras. The discussion shouldn’t be about film OR digital but film AND digital. They both have so much to offer..

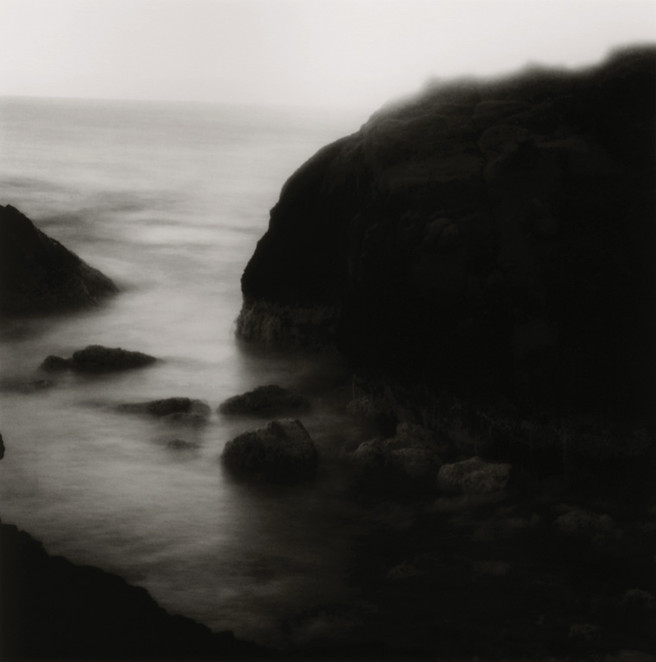

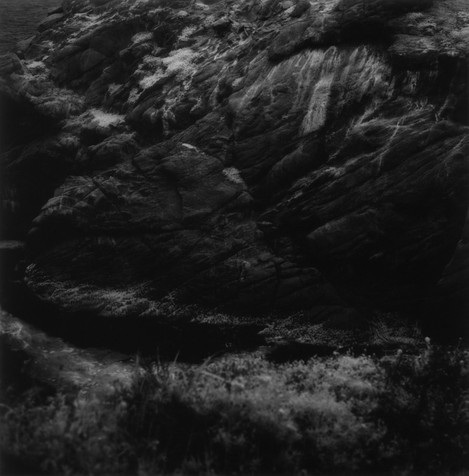

evertheless we pressed on. Although I know Saltwick well having collected fossils there for nearly 40 years and taking pictures since the late 1990s it is somewhere that I always find difficult to get your eye in when the conditions are less than perfect. The temptation is to return to old favourites, search out some well loved bits of sandstone or old jetty or cliff. The high cliffs unbalance any image that includes them, they are dark rock and mostly in shade. Working under them is slightly hazardous (especially recently as cliff ‘showers’ and falls have been more frequent since the 2013/14 Winter) but can be rewarding. I had a new Samyang 24mm F1.4 lens in the bag that I wanted to try on the A7R and found an image that would serve that purpose.

evertheless we pressed on. Although I know Saltwick well having collected fossils there for nearly 40 years and taking pictures since the late 1990s it is somewhere that I always find difficult to get your eye in when the conditions are less than perfect. The temptation is to return to old favourites, search out some well loved bits of sandstone or old jetty or cliff. The high cliffs unbalance any image that includes them, they are dark rock and mostly in shade. Working under them is slightly hazardous (especially recently as cliff ‘showers’ and falls have been more frequent since the 2013/14 Winter) but can be rewarding. I had a new Samyang 24mm F1.4 lens in the bag that I wanted to try on the A7R and found an image that would serve that purpose.