End frame: Hashikui Rocks, Study 1, Kushimoto, Honshu, Japan, 2002 by Michael Kenna

Do you have a favourite image that you would like to write an end frame on? We are always keen to get submissions, so please get in touch to discuss your idea. You can read all the previous end frame articles to get some ideas!

Michael Kenna was one of the first photographers whose books I felt the need to buy, so that I could have his photographs at home and look at them whenever I wanted (The Internet was still not omnipresent in our lives back then).

Opening his books was always a small ritual for me; I still handle them like precious objects, because going through his photographs feels like traveling and almost taking a holiday.

I find that while his style is clear and consistent, the variety of his work is very big, so many photographs stands out for themselves.

I chose to write about Hashikui Rocks, Study 1 for End Frame because in my opinion it represents very well why I admire Kenna’s work.

At first glance, it is a very simple image – just some rocks and their reflection in the water. However, the more time you spend looking at it, the more facets you notice and the deeper the picture becomes.

For example, the line of the rocks could be interpreted as an electrocardiogram, maybe a seismogram. Or it could be read as a faraway landscape with some mountains and skyscrapers, a combination of silhouettes, some of which are man-made and others that have been created by nature over time. So I could state that this picture is a perfect subject to see how much one can project and read on a square piece of paper with just a few different tones of grey disposed in a composition which is at the same time a clearly identifiable object but also could be quite abstract.

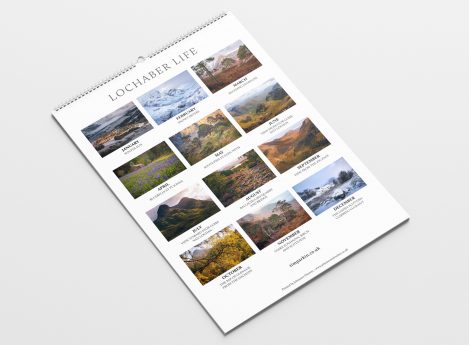

2026 / 365

I’ve mentioned before that I haven’t had much dedicated time for landscape photography over the last couple of years. That’s mainly because I’ve been spending a lot of time in the mountains, where photography was still happening, but usually as a secondary concern to whatever I was out there doing.

After Matt Payne’s visit last year, I realised I probably needed a project, something with enough structure to nudge me out the door more regularly. So I’ve restarted a practice I first tried about five years ago, taking one photograph a day for the whole of 2026. January has gone reasonably well so far, although a bout of Covid made me miss a day and also led to one slightly questionable “photo through the bedroom window” attempt, which felt a bit like cheating.

I thought it might be interesting to share how the project unfolds, so I’m going to post a monthly update with a small selection along the way. Each month, I’ll include eight photographs with captions.

Achtriochtan Snow Storm - 2nd January

A tourist vantage point, but one with so much photographic potential in the right conditions. Around 3 pm, a series of snow/rain bands was due to pass. I went to the edge of the lochan and I found a satisfying clump of reeds to provide a foreground ready for the front to arrive. Just as the squall was blowing in, I had time to capture three frames before the wind hit the water. Shortly after, the view disappeared and so did the feeling in my fingers.

A critical part of making this photo was finding a clean area of water in the foreground, which was just as important as finding a complementary grouping of reeds. I wasn't 100% successful; a couple of the foreground reeds stood out. However, a bit of contrast reduction in Photoshop/Lightroom did the trick. The same processing was applied to a couple of car headlights in the background. The key to post-processing this image was to enhance the contrast between the cool blues and the warm reeds/lower hillside.

Any Questions, with special guest Norman McCloskey

The premise of our podcast is loosely based on Radio Four's “Any Questions.” Joe Cornish (or Mark Littlejohn) and I (Tim Parkin) invite a special guest to each show and solicit questions from our subscribers.

In this episode, Tim Parkin and Mark Littlejohn talk to Norman McCloskey about his journey from sports photography to becoming a renowned landscape photographer in Ireland. He discusses the importance of authenticity in art, the challenges and successes of running his own gallery, and the significance of self-publishing his books. Norman emphasises the emotional connection to the landscape in his work and the unique approach he takes in his photography. He also reflects on the thriving gallery scene in Ireland compared to the UK and offers insights into the business side of photography.

Read more:

- An interview about Norman's Beara Peninsula body of work.

- An interview about his Kingdom Project.

- a review of his Park Light book

- and about his "Devil's Island" image.

Spirituality

...experience thrives on engagement and participation rather than doubt and detachment. It is constituted by numberless acts of intuition, discernment, and judgment whose full import stands to be sifted in dialogue with other members of the interpretive communities we inhabit. ~Thomas Pfau

Resonance was described as a relationship based on action and intuition with a practical description of three modes: Iconic, Schematic, and Conceptual. This article looks beyond the surface for a deeper resonance in the spiritual domain and the role photography plays.

Spirituality is a sensitive subject because it touches the core beliefs of many people.

The first type of spirituality is Mystical Spirituality, which is an orientation towards the ineffable. The second type is Secular Spirituality, which is an orientation towards the “actual.” The third, not addressed in this article, is Religious Spirituality, which is found in churches, temples, and theology.

Mystical Spirituality

The goal of Mystical Spirituality is the experience of immanence and/or transcendence, or the infinite and the eternal. As far as the everyday world of experience goes, it is a form of detachment from the finite world of the “actual” (Critical Realism).

Feli Hansen

What transpires when, instead of excluding human traces from your photographic compositions, you make them the subject matter? Feli Hansen’s Guilty Trashures caught my attention while reviewing the results of the Natural Landscape Photography Awards 2025. In the Project category, as runner-up, was a series of landscapes that bore a striking resemblance to natural landforms and elements. Only upon closer examination and reading the description did it become evident that these were, in fact, plastic. It was refreshing to observe not only a photographer choosing to draw attention to something that has become so commonplace that it is imperceptible to some, but also to witness the work receiving recognition on its merits. This project reminds me, in a positive way, of Mandy Barker’s work, and similarly, Feli Hansen has recognised that to engage the viewer, it is necessary to make something awful, aesthetic.

Looking through Feli’s Instagram feed, it was apparent that this was not all that we could feature here. While she has visited some of those tick-list locations (Iceland, the Lofoten Islands), her interpretations remain personal in their composition and style and draw on the time she has spent photographing the coastline close to home.

Tell us a little about yourself, Feli – where did you grow up, what early interests did you have, and what did you go on to do?

I was born in Hamburg, Germany. Due to my parents’ work, we moved several times in my first six years. From Germany to The Netherlands to Belgium and back to The Netherlands. Unfortunately, my dad passed away unexpectedly when I was four.

As a child, I loved being busy creating things, just like my mother and brother. It could be anything from drawing, painting, carpentry, sewing, cooking, or whatever. It's so satisfying when you make something yourself. I also enjoyed reading nature books and watching nature documentaries, besides sports like swimming, windsurfing, and playing tennis or just playing outside with friends.

Walking with Tolkien

The story of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has taken me to many destinations over the past twelve years. Living near the landscape of the Brecon Beacons has always offered the potential for regular visits, documenting what could easily be imagined as The Shire. The rolling hills of the Beacons, so familiar to Tolkien during his childhood, and the musical tones of the Welsh language may well have influenced many of the names and places we now know in Middle-earth. You can read my previous articles on Tolkein are: Tolkien’s Shire in Lord Of The Rings & Walking in the Shadow of Middle Earth.

Later in life, Tolkien travelled to Italy, a country he adored for its culture, food, and the dramatic topography of its landscape. The jagged peaks of South Tyrol and the Dolomites seem to echo through the mountains of Middle-earth. In Tolkien’s time, what is now northern Italy — possibly the inspiration for Mordor — would have been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, later reshaped by the tides of European history.

I have spent many hours walking through these landscapes, imagining what Frodo might have felt as he struggled to return the Ring to the mountain where it was forged — or what it would be like to plant crops in the Shire, drink fine ales, and smoke a pipe beneath a broad-leaved tree.

As I’ve mentioned in my previous articles on this long journey, Tolkien’s world can sometimes become political territory. He is revered worldwide, and his work is taken with great seriousness — occasionally too seriously. Over the years, I’ve heard heated debates among academics, each trying to prove that their interpretation of Tolkien’s travels and inspirations is the correct one. I’ve even heard a few bitter words exchanged about whose “Middle-earth” is the true one.

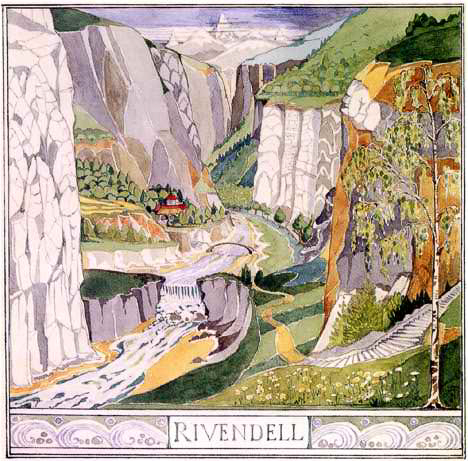

However, there is one place where argument seems unnecessary, a location backed by Tolkien’s own words and sketches: Rivendell, or as it is known in the real world, Lauterbrunnen in the Swiss Alps.

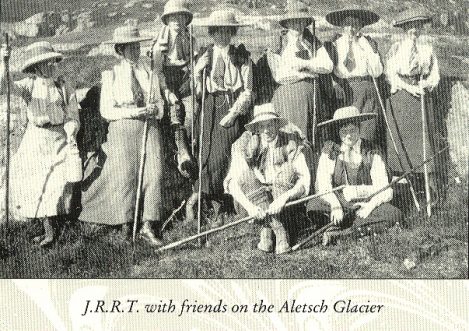

During the year 1911, when Tolkien was just 19 years old, he was invited to join a group walking in the Swiss Alps. The trip was initiated by the Brookes-Smith family, who had visited the region on a number of occasions before the First World War. Tolkien, along with his aunt and others, spent a few weeks in July and August travelling on foot through what we now know as the Misty Mountains. The Swiss Alps were his first experience of the heady heights of a serious mountain range. It is clear from his documented letters that this landscape inspired the mountainous peaks of Middle-earth, including Rivendell.

Rivendell, or Imladris, was an Elven outpost in the Misty Mountains on the eastern edge of Eriador. Due to its location, it was called the Last Homely House from the point of view of a traveller going eastward into the Misty Mountains and Wilderland, and the First Homely House for those returning from the wilds to the civilised lands of Eriador in the west.

It was established by Elrond in the Second Age, year 1697, as a refuge from Sauron after the fall of Eregion. It remained Elrond’s seat throughout the rest of the Second Age and all the way into the end of the Third Age, when he finally took the White Ship to Valinor. Rivendell maintained a strong alliance with the Kings of Arnor, and after the fall of Arthedain it became a sanctuary for the Rangers of the North and the Heirs of Isildur.

If I ever dedicate a full book to my travels in search of Middle-earth’s real-world counterparts, this is one place that must be included. My visit to Switzerland was originally for a lecture at a college in the medieval town of Fribourg, but Lauterbrunnen was only a three-hour drive away. I couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit what is widely accepted in Tolkien scholarship as the home of the Elves.

My research started by revisiting the maps of the tour that had been documented. I also contacted the Tolkien Estate for information on any writings or artwork created after his visit. I then planned the more remote drive to the region, documenting my journey along the way.

After a brief stay in Fribourg, I set off across the lofty hills — what the Swiss modestly call hills, though at over a thousand metres they would be considered mountains back in the UK. Driving through thick fog, I could hear the soft clanging of cowbells in the distance. It was November; the leaves were still clinging to the trees, glowing with late-season colour after a gentle autumn.

As I descended toward the plains near Thun, the fog began to lift, revealing the Alps towering over the landscape ahead. The road followed the shoreline toward Interlaken, sunlight now breaking through as signs for Grindelwald appeared. I was in the shadows of the mountains — vast, stony giants blocking the sun, their sheer faces gleaming with cold light.

The name Grindelwald reminded me of places not far from my own home in Wales, though here the landscape was on a grander scale. Turning off the main road, I drove deeper into the valley — into what felt unmistakably like Rivendell.

One of the things that strikes any visitor to Switzerland is how efficiently everything runs. The roads are smooth and orderly, trains seem to appear from nowhere, and infrastructure is woven cleverly into the landscape. Yet despite this sense of calm organisation, I felt a strange unease as the road narrowed and the valley walls rose higher around me — sheer rock faces climbing into the mist, silver birches clinging to the slopes, deep shadows pooling between them.

Also, another uneasy part of travelling to this destination was the sheer number of people. The roads were busy, walkers streamed in every direction, and helicopters flew in and out above the valley — reminding me of air traffic departing from London Gatwick. Surely this would not have been the case when Tolkien visited as a young man. In his time, Lauterbrunnen must have been a place of quiet isolation, where the only sounds were the waterfalls, the wind through the trees, and perhaps the scratch of his pen in a notebook.

Then, rounding a bend, I passed the sign for Lauterbrunnen. The valley opened up before me — waterfalls spilling down the cliffs, chalets tucked among trees, and the sound of water and wind mingling in the air. There was no mistaking it. I had arrived in Rivendell.

The Hypnosis of the Tripod

Over the last few years, I’ve seen various comments about people no longer using tripods. Perhaps making disparaging comments about them. I’ve never encouraged people to change their style of shooting and burn their tripods. There is no right way and no wrong way to make a photograph. Some people use a tripod because they have unsteady hands and find it impossible to take a sharp image without the steadying influence of a tripod. Some might feel a better connection to the landscape when they use a tripod. It slows them down, their breathing steadies, and they can relax and see clearly.

It might be that you're slowing down a shot. Perhaps slowing it down to a second or two. Maybe even a minute. Some. And I'll use David Ward here as a prime example, shoot the most beautiful landscapes in miniature. Everything sharp. Tilted and shifted to perfection. A tripod isn't just desired, it's essential. Others will take similar shots of minutiae that will require those dark arts known as focus stacking, and again, a tripod isn't essential.

But I do have a couple of tiny issues. Firstly. How do you set the tripod up in the first place? I live in quite a picturesque part of the world. There are often little groups of photographers dotted around our landscape. They usually stand side by side in a neat little row and have the tripods lined up in front of them. They are all set to eye height for the user. No ricked necks or creaky knees for them. Cameras aligned horizontally. It always makes me wonder who we are setting up the tripod for? Us? or the view? I’m a firm believer that there is one absolutely right place to take an image from. Perspective is king. You have to decide what that perspective is before you start extending the legs of that leggy thing. The right perspective is very rarely precisely at eye height.

Another problem is a tripod's ability to hypnotise its owner. I was on Luskentyre recently, and I saw an unknown photographer on the beach. Tripod set up facing the sea. There had been some nice light catching the curling waves. A wonderful luminance as they folded in upon themselves. But that light had paused, flickered and vanished. The gent, however, was still transfixed by the rear LCD screen of his camera. Oblivious to the views on either side of him.

I have no issue with setting up a tripod and then leaving it in the same space for prolonged periods of time. You might love a composition, and you're just waiting for that wondrous bit of light a la Julian Calverley. But step back from time to time. Remove your gaze from the back of the camera. Let your shoulders relax a little. Take a long, slow look around you. Over your left shoulder. Your right shoulder. I think a 35mm lens has a field of view of around 60 degrees. Much the same as your eyes. Which means that, thanks to the hypnotic effect of that three legged thing in front of you, you’re ignoring about 80% of the world around you. At the end of the day, all I’m saying is, keep the tripod, but use it wisely.

Don’t let the tail wag the dog.

Issue 343

End frame: Les Grandes Jorasses, by Pierre Tairraz

Do you have a favourite image that you would like to write an end frame on? We are always keen to get submissions, so please get in touch to discuss your idea. You can read all the previous end frame articles to get some ideas!

As so many others have written, the email from Charlotte asking me to contribute to the end frame series came as a surprise, a wonderful honour really, yet at the same time one that filled me with dread: how can I possibly choose a single image from so many that I’ve seen by world-class photographers, some of whom I am fortunate to know having participated in their workshops over many years.

Quite coincidentally, when Charlotte’s email came through, I had been rummaging through my own old family photos, some of which took me right back to 1968 when I had my first glacier hike with my parents in the Chamonix Alps. Both my parents loved camping holidays in the mountains, in fact, Dad was an accomplished mountaineer, having opened several new routes in the mid-late 1930s in the Austrian Alps and the Tatra Mountains in Poland and what is now Slovakia.

And that gave me the idea of choosing an image by Pierre Tairraz (1933 – 2000), a guide from the Tairraz family of Alpine guides in Chamonix. He had studied cinematography, but in my opinion was also a superb stills photographer of the High Alps, working mostly in Black & White. Many of his photos were exhibited in the Tairraz family shop: wonderful silver halide 16”x20” prints, with deep shadows yet controlled highlights.

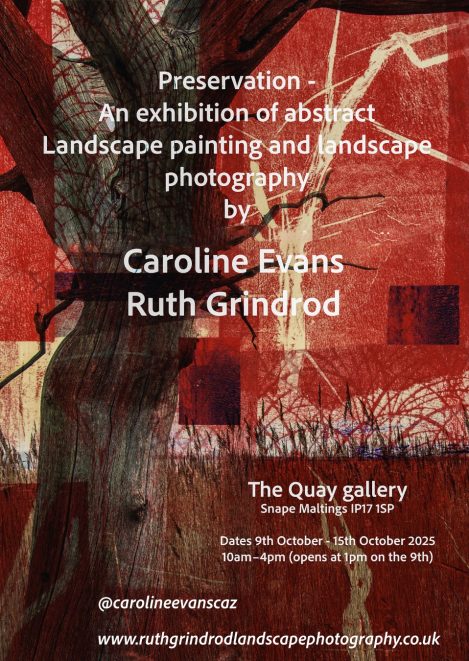

4×4 Landscape Portfolios

Welcome to our 4x4 feature, which is a set of four mini landscape photography portfolios that have been submitted for publishing. Each portfolio consists of four images related in some way. Whether that's a location, a project, a theme or a story. See our previous submissions here.

Submit Your 4x4 Portfolio

Interested in submitting your work? We are always keen to get submissions, so please do get in touch!

Goran Prvulovic

Alberta’s Gold Beneath the Sky

Kate Snow

Mountains of Ice

Uwe Beutnagel-Buchner

Scotland's Native Woodlands

Yasser Alaa Mobarak

El-Max Lighthouse in El-Max Region, West Alexandria, Egypt

El-Max Lighthouse in El-Max Region, West Alexandria, Egypt

El-Max Lighthouse in Alexandria stands as a quiet sentinel on the edge of the Mediterranean, where the sea meets history. During my recent visit, I had the chance to capture this timeless structure through my lens at three of the day’s most captivating moments—sunset, sunrise, and the magical blue hour. At sunset, the lighthouse glowed against a sky brushed with gold and crimson, while at sunrise, it stood serene under a soft blush of light. During the blue hour, just before night fully embraced the coast, the lighthouse became a silhouette of solitude and strength, framed by deep hues of indigo. Each moment offered a different story, revealing the enduring beauty and silent grace of El-Max Lighthouse.

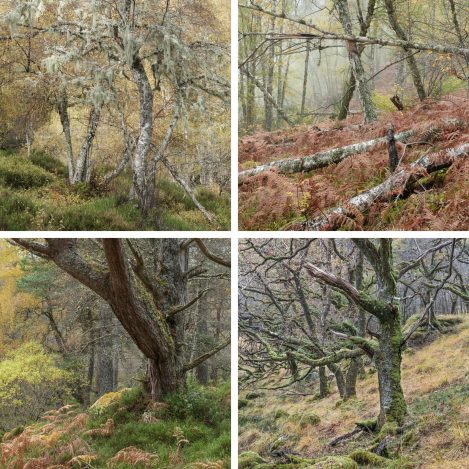

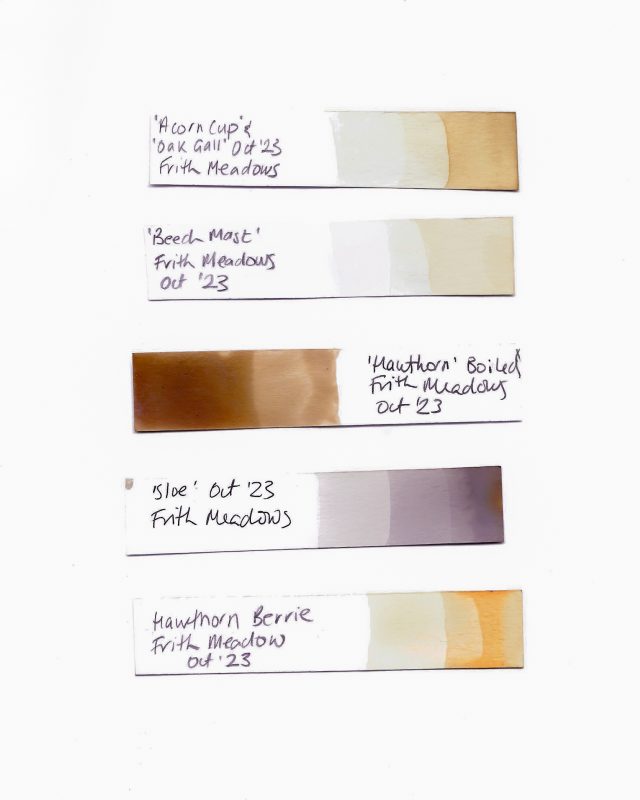

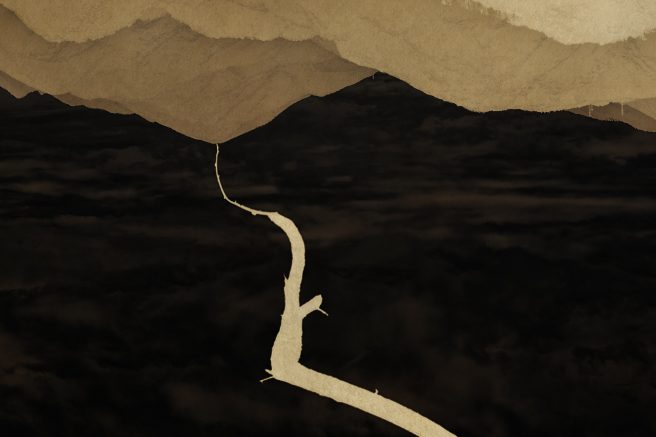

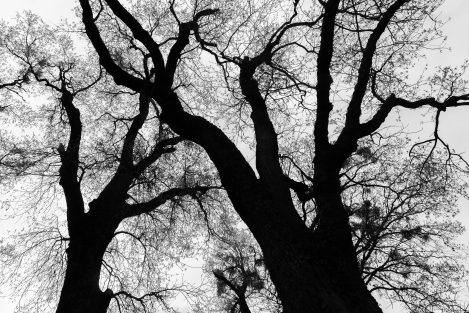

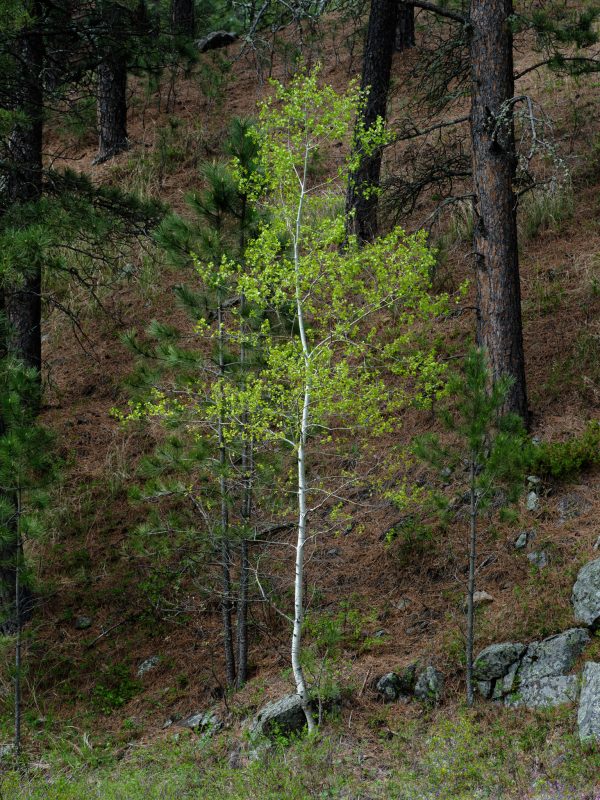

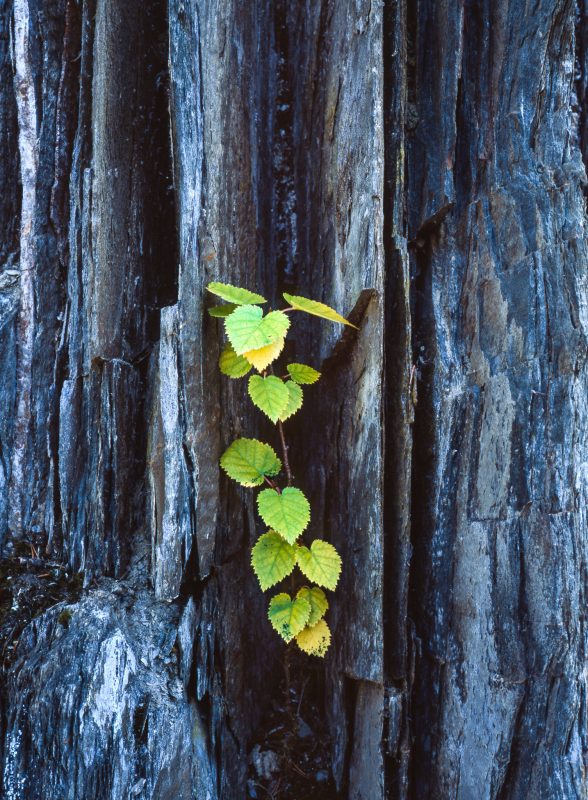

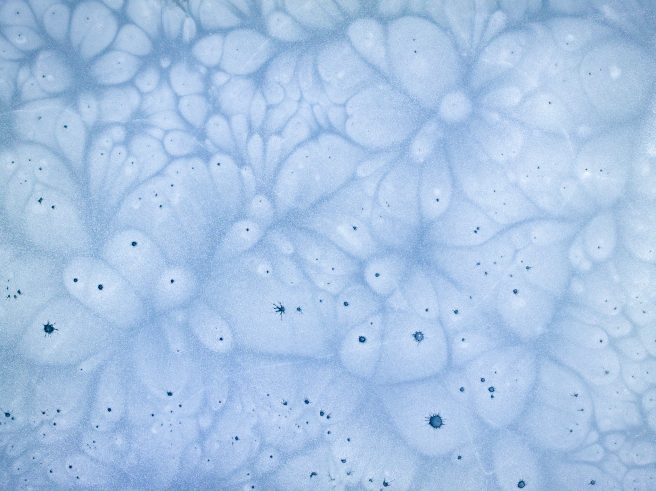

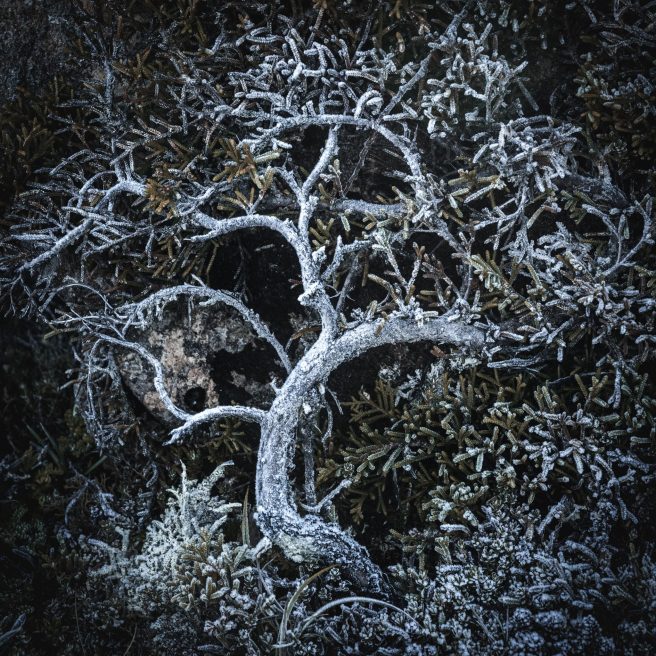

Scotland’s Native Woodlands

These images are part of a running project which objective is to generate attention on preserving, rewilding and expanding native woodlands. It aims to support such activities of private people and organizations by trying to photographically convey the attractiveness, the wealth of species, but also the fragility of native woodlands. The hope is that the images will raise awareness and trigger a reflection in the viewer about what is possible, even in their own region. Scotland's Native Woodlands can serve as a good example here.

The photographs show glimpses of various native woodlands. They are intimate treescapes that show deeper impressions and details of the individual habitats rather than their embedding in the surrounding landscape. The aim is to draw the viewer into them and make him feel part of them.

The overall collection of photographs was taken over some years in several nature reserves, which has been identified by Scottish Forestry, a Scottish Government agency, based on the “Native Woodland Survey of Scotland”. The nature reserves are located

- in the Highlands of Perthshire,

- in the coastal areas of Argyllshire,

- in the Beinn Eighe and Loch Maree Islands National Nature Reserve,

- in the Affric Highlands, and

- in the Cairngorms National Park, Strathspey and Deeside.

The term “native woodlands” generally refers to woodlands with trees and shrub species that have settled naturally, without human intervention. In Scotland, this happened after the last ice age around 9,000 years ago, when the seeds of these native trees were dispersed by wind, water and animals. As a result, extensive forests of oak, pine, birch, alder, ash, hazel, willow and other trees and shrubs formed. Depending on the topographical location and climatic conditions, different types of forest developed, including temperate rainforests in the warmer and wetter west of Scotland, Caledonian pinewoods in the Highlands and in the east of Scotland and birchwoods at cooler, higher altitudes and at wetter, lower altitudes.

Dario Perizzolo – Portrait of a Photographer

There are a few questions worth asking before we ever raise a camera to our eye. Who are we making photographs for, and why does that answer keep changing over time? What happens when the thrill of new gear or fleeting attention fades away? And perhaps most importantly, what role do we actually want photography to play in our lives, not just as image-makers, but as people moving through the world?

These are not abstract questions for Dario Perizzolo. They sit at the center of his photographic journey, shaping not only what he photographs, but how photography has become integrated into his sense of purpose, community, and daily life. His images, often quiet, contemplative, and rooted in familiar landscapes, reflect a deeper recalibration, one that many photographers eventually face, whether they realize it or not.

Like many creative paths, Dario’s began early and innocently. His first exposure to photography came not from chasing epic scenes or technical mastery, but from watching his mother make simple panoramic images during family trips to Italy. They were humble constructions, film frames taped together and hung on the wall, but they carried something powerful. They were personal, tangible, and deeply meaningful. That early sense of magic lingered, even as photography remained mostly in the background through his younger years, present but not yet fully claimed.

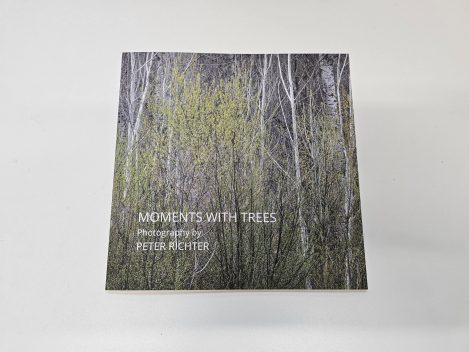

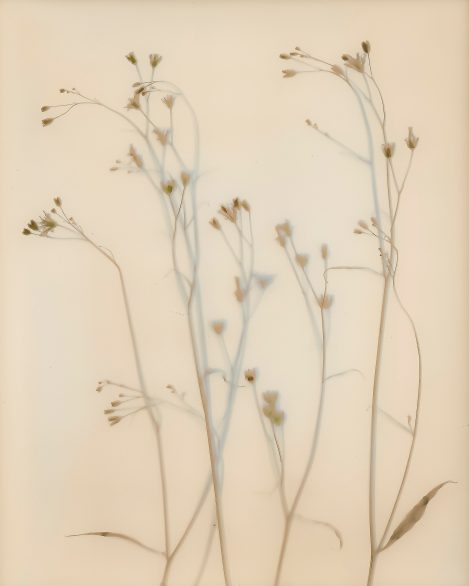

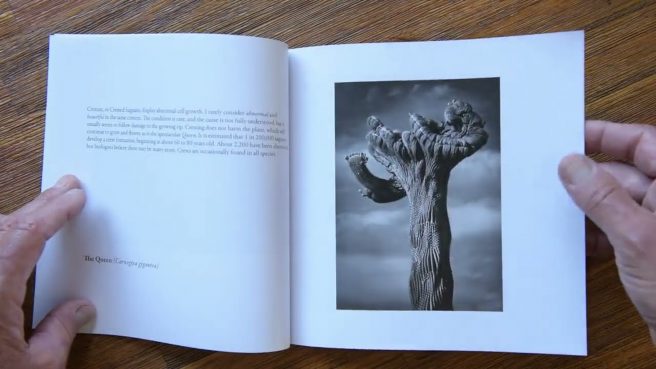

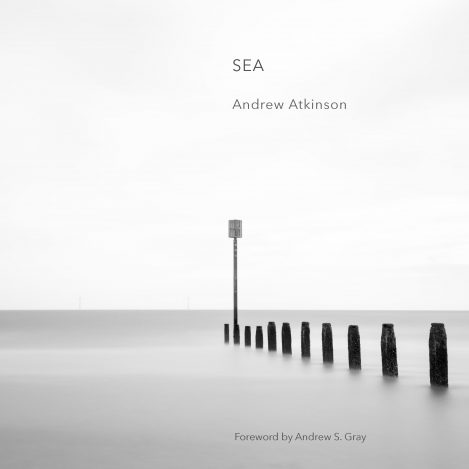

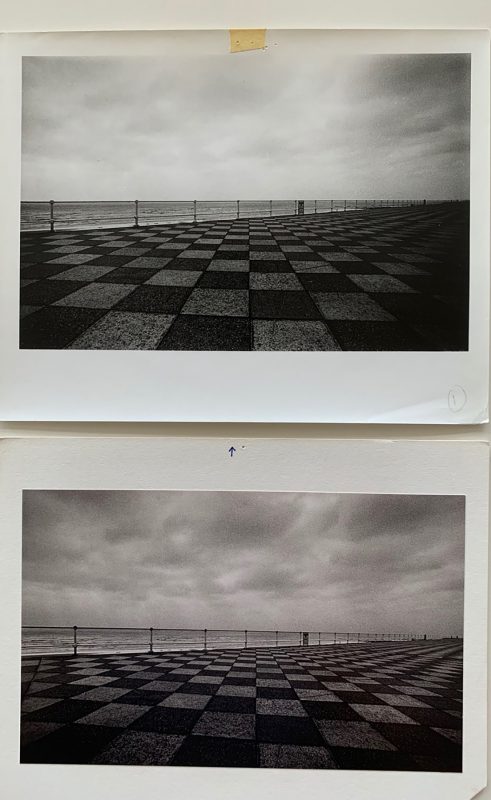

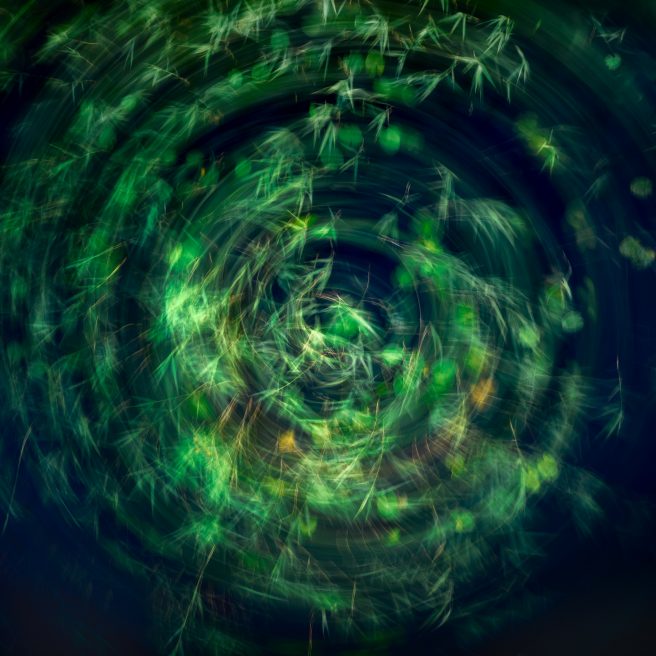

Stillness. In Motion.

I never set out to create a photographic project, and certainly not a book. If someone had told me in late 2020 that I’d soon be spending most of my days walking the countryside with a camera, making abstract images of wind-blown grasses and slow-rolling waves, I wouldn’t have believed them.

At the time, I was trying to navigate a sudden redundancy that had brought my thirty-six-year career in film production to an abrupt end. It meant not only financial uncertainty but also a deep sense of personal and professional loss. On top of that, the strangeness of lockdown cast its own uncertainty across daily life. For a while, I felt adrift. Yet in the midst of that turbulence, photography re-entered my life, and it quickly became my anchor.

Photography had always been a quiet passion, lingering in the margins of my busy working life. Within days of losing my job, I upgraded my camera, and within weeks, I had left London. Suddenly, I had time, and the countryside was on my doorstep. During lockdown, when travel was prohibited, the same fields, lanes and woodlands became my sanctuary.

Photographing every day in the same area challenged me to interpret the same places in different ways.

I began to see differently. The landscape was unusually quiet, and within that stillness I became captivated by motion - not just ripples of water or grasses bending in the wind, but subtler gestures such as the sweep of a branch or the rise and fall of hills. I began experimenting with long exposures and moving the camera mid-shot, and became fascinated by how I could capture something of the ephemeral. At the time, I had no idea what I was doing in any formal sense.

I hadn’t heard of intentional camera movement and was simply following instinct, excited by the potential in these blurred, gestural images. It was only much later, when someone commented “ICM?” on a photo I’d posted online, that I discovered it was actually a thing - a technique - after looking it up. That discovery gave a name to what I had already been exploring intuitively and encouraged me to push further into abstraction. I also began experimenting with multiple exposures, intrigued by how layering could expand the possibilities even more.

When lockdown finally lifted, and I was able to travel to the coast, it felt like breathing out after holding my breath for months. After so long walking the same paths near home, the sudden expanse of sea and sky was overwhelming in its freedom. The horizon seemed to stretch forever, and with it came a sense of release I’d been craving. I spent hours on the beach, entranced by the shifting tide and the motion of the sea. Long exposures smoothed the waves into flowing veils, and intentional camera movements transformed shoreline and sky into abstract bands of colour.

Each frame felt like a discovery, a dialogue between myself, the sea, and chance. The excitement lay in seeing these images emerge, not as records of a place, but as expressions of how it felt to stand there - liberated, quietly elated, and beginning to glimpse where this exploration into motion might lead.

In many ways, it led me back to my beginnings. Looking back now, I realise my early training as a dancer left a lasting imprint on me; movement has become woven into the way I see the world and continues to shape how I engage with the landscape - and how I photograph it.

My photography became less about documenting what I saw and more about reflecting how I felt in nature. In time, I came to see that shift as both liberating and deeply restorative. The stillness of the countryside during lockdown was palpable, and within that wider quiet, I began to discover a stillness of my own. Looking through the viewfinder, I would lose myself, often entering a state of flow where everything else seemed to fall away. Photography offered a sense of calm not only when my own life had been upended, but also amid the wider upheaval of the world around me.

As the months passed, a thread began to emerge. Though the landscapes and subjects varied, the images shared a common quality: a lyrical stillness born from motion. I began to gather them into small collections – Landscape in Motion, Coastal Flow, Grasses - each exploring different facets of movement. Over time, new groupings emerged: Flora, where I’m drawn to the way the structure of flowers suggests a kind of dance, and Woodland, which centres on the flow and interplay of branches and trees. What intrigued me most was the paradox that the images with the most movement often conveyed the deepest sense of quiet, transforming the commonplace into something poetic.

It would be another three years before I considered the possibility of a book. Like many photographic projects, it evolved organically rather than from a predetermined vision. When the collection reached a certain weight, I knew it could be more than a series of images on a website or in an exhibition. It could become something tangible, a cohesive narrative. I was thrilled when Kozu Books saw the potential of the work and offered me a publishing deal, guiding it into book form.

Turning a collection of photographs into a book was exciting and rewarding, but it took time to find the right flow. The collections I had created became the foundation for the structure of the book, yet the sequencing went through many iterations, each change subtly shifting the mood and relationships between images. I enjoyed seeing how pairings across the pages could alter the nuance of the work and reveal new connections, though reaching that balance wasn’t always simple. Some of my favourite images didn’t make it into the final edit but letting them go became part of shaping something cohesive. After many rounds of adjustments, the book finally settled into a rhythm that felt authentic to the work and true to the way it had begun.

On reflection, the seeds of Stillness. In Motion were sown during those early lockdown walks. There was no grand idea at the outset; I was simply responding intuitively to what was in front of me, enjoying the serendipity of a practice where chance plays such an essential role. With ICM and multiple exposures, there is only so much you can control. That unpredictability was, and still is, a source of joy.

One reason I am drawn to abstraction is that it leaves space for emotion. By stepping away from literal representation, I can create images that suggest rather than describe, inviting viewers to bring their own responses, shaped by memory and experience.

Over time, I’ve come to see Stillness. In Motion. not as a project, but as a journey of discovery. It was born out of change, guided by intuition, and shaped by the landscape itself. There was never a plan, and that, I think, was essential. Each photograph was simply the result of being present in a moment, of paying attention, of letting chance play its part. The book gave form to that journey, but the practice remains open-ended - a way of seeing that continues to unfold.

Purchase Information

Stillness. In Motion is available from Sally's website or from Kozu Books, from £40.

Gallery

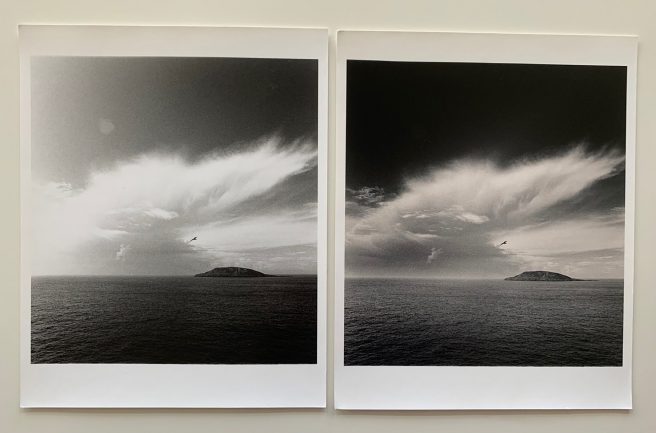

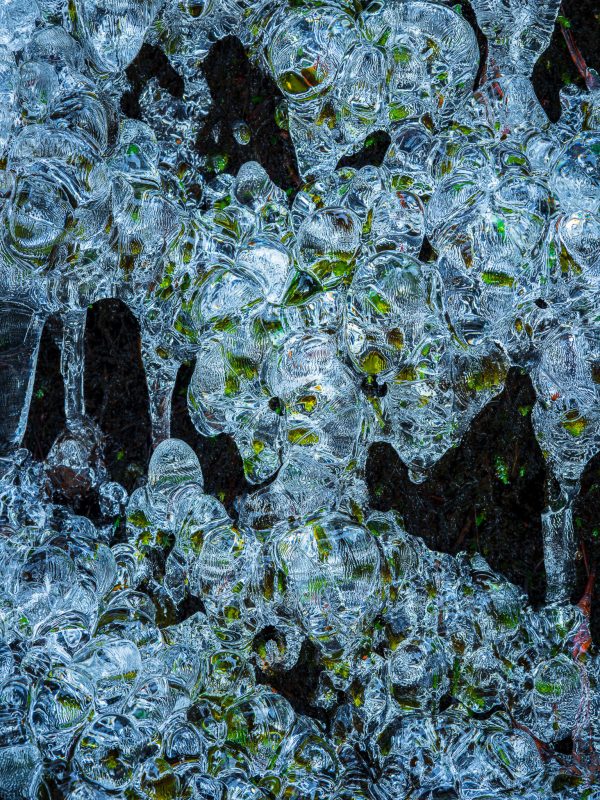

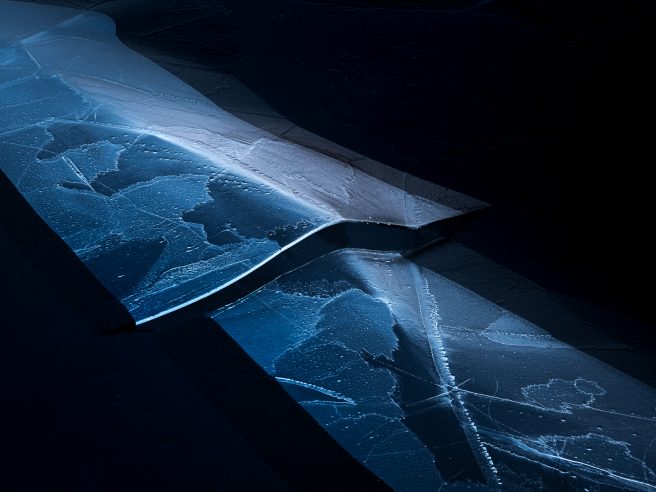

Mountains of Ice

“Mountains of Ice” is a monochrome photographic series that explores the beauty of the world’s frozen mountainscapes. Through black and white imagery, the absence of colour is intentional: highlighting the form, contrast, and texture of ice and snow, and inviting viewers to contemplate not only the aesthetics of these remote landscapes but their vulnerability.

Shot in extreme environments, the series emphasises the majesty of places at the edges of the planet and that have been shaped over millennia. While beautiful to behold, the images also reflect the stark reality of our changing climate. By stripping away colour, the work underscores both the endurance and fragility of these landscapes, providing a quiet call for viewers to attain a renewed appreciation and desire to preserve these frozen landscapes.

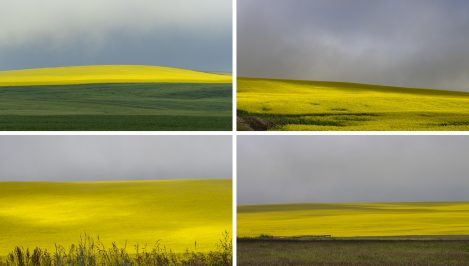

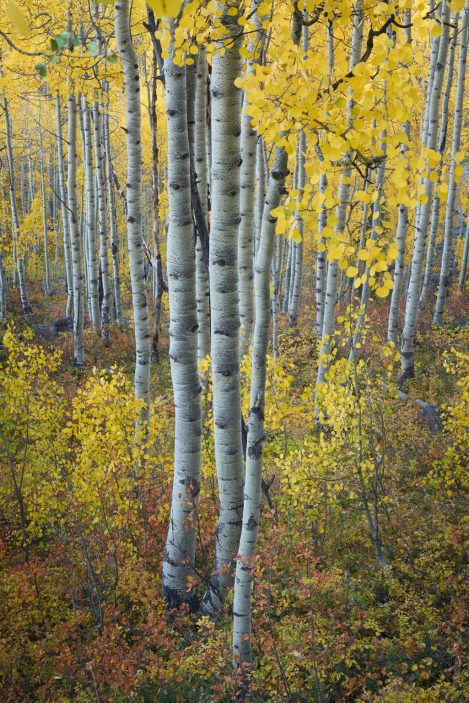

Alberta’s Gold Beneath the Sky

More than just mere farmland, Alberta’s yellow canola fields transform into a sight right out of a 20th-century impressionist painting. To the ordinary eye, the rolling hills of rural Alberta are an everyday sight. But sometimes, when the light and weather are just right, the canola fields become a veritable Von Gogh of colour and texture. The clouds overhead, casting ever-changing shadows like a celestial painter casting brushstrokes upon a canvas of yellow and green.

Moments like these are harder to find than you think. When you’re in the right place at the right time, when the sunlight’s just perfect, fields of ordinary canola and wheat become truly magical. Other times, a field is just a field, and the magic just isn’t there. You can drive hours and not find a perfect shot. But more often than not, right when you’ve given up and are heading home, the perfect shot seems to find you.

Bill Ward

Bill is a photographer whose work is shaped by experience rather than observation alone. His images feel lived, and emotionally direct, often placing the viewer within the landscape rather than at a comfortable distance from it. Ward’s route into photography was anything but linear. After beginning his working life in advertising, where clarity of ideas and originality were paramount, he retrained as an actor and has since sustained a long and successful career on stage and screen. Photography emerged later as a necessary counterweight, a quieter, more solitary practice rooted in instinct, presence, and attention.

You began your working life as an advertising executive, then moved into a long and successful acting career, and now you are known for your landscape photography. Can you tell us more about that journey and how each stage led to the next?

Well, I’d like to say it’s been one long, seamless, meticulously planned voyage, but actually it’s all been way more haphazard than that, although it’s generally made a fair amount of sense at the time. A lot of it has been about following my nose, having a bit of a feeling, and then taking a very deep breath and trying to do something about it.

I worked for two of the big UK Ad Agencies, BBH and Saatchi & Saatchi, as an Account Director and Strategic Planner for a decade or so after coming out of University. I’ve got a History Degree, but I’d always been fascinated by adverts on the tele growing up. Human behaviour, what makes people do what they do, and why they do it, is essentially the raw material of both Advertising and History, also Acting, but we’ll come on to that!

I loved Advertising for the ideas, the purity of them in particular - having 30 seconds to tell a story as clearly and as concisely and memorably as you can. But it also taught me the importance of originality - the value of creativity and original thought.

I went travelling for a couple of years in my late 20’s and early 30’s, there was so much of the world that I hadn’t seen, and I was feeling a little bit empty at the time and that I really needed to put something new and unexpected back in - and when I came back, I took the plunge and did the only other thing I’d ever truly wanted to do, which was be an actor. I’d done loads of plays through school and university, and had loved the freedom of it, the self expression of it, the exploration of it. So I put myself through drama school when I was 32, came out when I was 33, and I’ve been an actor ever since.

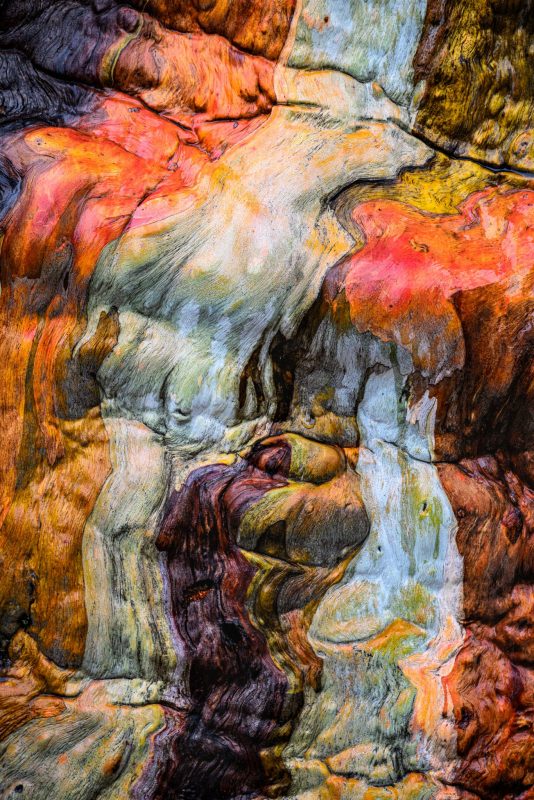

Without a plan to the Opal Coast

Intimate landscape with different kinds of rocks, photographed on the beach at Cap Gris Nez. I used focus stacking to make the image completely sharp.

In October last year, I did something I hadn’t done in a long time: I took a (short) photo trip, without having a project in mind for which I would use the photos I took, and without concrete ideas for photos I would make. In other words, I ventured out completely unrestrained!

For many of you, this may be the standard way of traveling and photographing. That was how it used to be for me as well, in the years when I had just started nature- and landscape photography. But over the years, that has changed quite a bit. Nowadays, I basically always go out for a project. And if it isn’t an ongoing project, then it’s at least a scouting trip for a potential project.

This is partly because you focus more precisely and intensely on a subject, and you delve into your subject more deeply, which eventually makes you notice and photograph things you wouldn’t otherwise notice. In addition, working with a clear goal gives me a sense of calm. In the past, I often wanted to do too many things at once, went out with an overfull photo backpack, and nearly panicked when the conditions were beautiful because there were so many possibilities. I also wanted to exploit all those possibilities and turn them into concrete photos. But in practice, this usually proved impossible and even led to frustration, because I would return home with many photos, but none of them really stood out. With a project in sight, it’s much easier to let other options fall away on a beautiful morning, so I work with much more calm and usually come home with better photos.

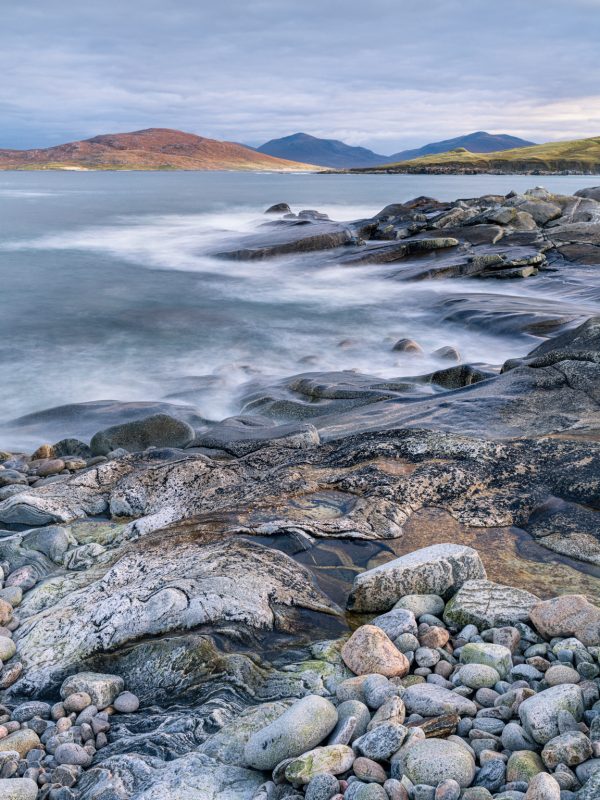

Eight Vignettes of Torridon

‘Vignette’

/viːˈnjɛt,vɪˈnjɛt/

Noun

1. a short graceful literary essay or sketch

2. a photograph, drawing, etc,

with edges that are shaded off ~Collins dictionary

The mountains of Torridon have a way of holding you at a distance. Sheer sandstone walls rise from the glen with an authority that resists easy capture. Its mountains are spoken of in reverent tones – Liathach, Beinn Alligin, Beinn Eighe – names that carry the same weight as their ridges and peaks. I was first made aware of these mountains three years ago, when my photographic journey began. Long before setting foot, I spent hours poring over maps and photographs, sketching out routes and viewpoints within this fabled range.

This early fascination made returning inevitable, but as a student, travel required planning and compromise. Scotland’s free bus travel scheme for under 22s offered me both an opportunity and a challenge.

The network stretches far, from comfortable city coaches to old school buses rattling along the Highland roads. But Torridon lies on one of the most restrictive routes: just two buses in and out on Tuesdays and Saturdays, providing a strict time window. For me, reaching it requires three separate connections and around eight hours of travel from the central belt of Scotland. The journey north became a kind of pilgrimage in itself – a reminder that Torridon insists on patience and commitment, before even reaching the trailhead.

The idea of merely revisiting felt incomplete. I wanted to give the journey more purpose, something that would make the effort of reaching this remote range feel intentional. On that long ride I had time to refine my aim. I set myself a challenge: to create a single photograph for each of Torridon’s eight peaks within the Torridonian Forest locality.

Not simply a record shot or a summit view, but a photo that represented each mountain’s presence and character. This demanded a slower pace. Rather than chasing every viewpoint, I had to move with the rhythms of the weather, attentive to its shifts and silences.

Backpacking gave me this freedom. With four days of food and shelter strapped to my back, I could linger when the conditions aligned, camp where the light lasted, or move on when the moment had passed. The weight of the pack was its own discipline, ensuring every stride was well measured, every stop deliberate, and every frame considered

Each mountain revealed itself differently – sometimes simply through waiting for the sun to be low enough for the right light, more often only after hours of mist or rain broke to let the light shape the landscape. What emerged was not just a record of a route, but a sequence of vignettes: eight mountains, eight photographs, each a fragment of Torridon’s story.

The word vignette feels fitting, suggesting both a short, graceful narrative and a technique for framing a scene. Together, they aim to form a portrait of Torridon – not complete, but true to the fleeting, elusive nature of this mountainous area.

Beinn Dearg – 914m

Beginning with Beinn Dearg felt fitting. It is an understated mountain – just 73 centimetres shy of Munro status, yet without the reverence or footfall of Torridon’s more famous peaks.

Sitting in the very heart of the range, it became both the epicentre for photographing this landscape and the original focal point of the trip.

I spent three hours wandering among a minefield of erratics, searching for compositions, hoping to be calm and prepared when the light finally arrived. In reality, it was the opposite. As the sun neared the horizon, the scene shifted into something fleeting and unpredictable: deep blue clouds layered high above, while white, lower clouds swirled around the summits. Panic set in. I raced between my previously scouted locations, watching how the changing light transformed each frame. Nothing sufficed.

At last, I arrived at a spot just as the foreground was descending into shadow. Ideally, I would have placed this rock further to the left of frame so that it pointed inward, but compromise was impossible.

Instead, I leaned into what the moment offered. Shadow and sun worked together, pulling the eye from the corners of the frame towards that solitary stone, now separated from Beinn Dearg by a rising line of shadow. In that brief instant, the layering I had been searching for finally presented itself.

Baosbheinn – 875m

The evening’s photography was far from finished. Having secured a frame of Beinn Dearg that felt strong enough, I turned my attention to Baosbheinn. With its long undulating spine, evoking the shape of a sleeping dragon, a faint wisp of cloud drifted from its summit like smoke.

I had climbed much of its ridge the previous day and carried with me a more personal sense of its place within the range. Baosbheinn is often treated as a lookout – a platform from which to admire the Torridon giants – rather than as a subject in its own right.

When composing the photograph, I let the light take the lead. The boulder field at my feet was chaotic, but within the disorder a group of rocks caught the sun and cast elongated shadows across the ground.

Their rhythm echoed the ridgeline beyond. I was drawn to the possibility of creating a visual echo – foreground stones arranged

like a miniature replica of Baosbheinn’s peaks, pulling the eye from right to left. In that moment, the mountain ceased to be just a viewpoint for Torridon’s giants; instead, it revealed a quiet authority of its own, connected by the rocks that lie beneath it.

Liathach – 1023m

I decided to save the privilege of traversing Liathach’s ridge for another trip, meaning I was only left to admire it from a distance, wishfully imagining the feeling of standing atop its peak. My glimpses of this mountain were handed in small portions.

However, when it did reveal itself, it was with great splendour. The light had drained from the surrounding mountains, leaving only a sharp, crimson glow clinging to the summit of Mullach an Rathain - one of the Munros of the Liathach ridge. Just as I thought the evening could offer nothing more, low cloud crept up behind the peak and began curling around the corner.

I worked quickly, using the converging lines of the surrounding mountains to draw the eye to Liathach, anchoring the composition with a foreground of neatly arranged rocks. Liathach’s grandeur was undeniable, even from afar. It was a mountain that revealed itself on its own terms as I was not to see its peaks for the rest of the trip, shrouded out by thick cloud.

Beinn an Eoin – 855m

The following morning, the weather that was originally forecast caught up with me. My short stint of good fortune seemed to have ended as I trudged up the steep 440m ascent to Beinn Dearg’s first summit, rain showers sweeping across in relentless succession.

As I reached the first summit, another seemingly targeted squall passed over me and onwards to Beinn an Eoin. A sudden patch of light broke through, illuminating one of the many lochans scattered across the glen, chasing the downpour into the distance. With the sun behind me, I watched with growing intensity as this dynamic scene unfolded. This was the moment I had been waiting for.

Starved for time and with little in the way of foreground interest, I sprinted to a pair of rocks that provided the necessary balance in this scene. Anticipation and exhilaration rose in equal measure as the first arc of colour edged into view. Slowly, the rainbow unfurled from left to right, light fighting against shadow for a foothold on the landscape until the scene resolved in full, fleeting brilliance.

Beinn an Eoin was the stage for this transformation – proof that patience and persistence, even through adversity, can sometimes coax magic form the most reluctant skies.

Meall a’Ghiuthais – 887m

At a loss for words after Beinn an Eoin, I wandered further along the ridge in search of capturing another mountain. I thought nothing I encountered would surpass what I had just witnessed.

Meall a’ Ghiuthais was always going to be one of the ‘make or break’ mountains for the success of this project. A solitary, stubby mountain which doesn’t immediately attract the eye.

This was a fortuitous encounter. Light and shadow once more wrestled above me, the cloud beginning to gain the upper hand as it swirled across the range, closing in on the surrounding mountains. In the distance, the sole-standing mountain was Meall a’ Ghiuthais – seemingly confined despite the vastness around it. I framed this photograph with striated rocks in the foreground, their lines pulling the eye into the centre and lending depth to its otherwise quiet presence.

At first, I dismissed the image. It felt forced, included only for the sake of the project and I questioned whether I would even have paused to take it on a regular trip. But the more I returned to it, the more it grew on me. I believe the reason I was doubting it, is part of the reason this image is just as special. A view and photograph that may be overlooked, but one that wouldn’t have been captured otherwise.

Beinn Alligin – 986m

The cloud settled in for good as I made the final push towards the summit of Beinn Dearg. Rain came in swathes across the ridge, turning Torridon’s usually reliable sandstone slick and uncertain. As I scrambled down, I was halted by a formidable boulder – standing defiantly amongst the otherwise obedient line of rocks beneath it.

Space to work was scarce. The ridge narrowed to barely five metres, leaving little margin for error. Each footstep had to be precise as I edged into position, seeking to line up the chain of smaller rocks, circling around the dominant boulder.

Flow has always been central to how I approach composition: how the eye moves through an image, where it rests, what interrupts its journey. While this can be refined in post processing, the core components need to be present with the composition.

As I fought to keep the lens clear with fierce, oncoming rain, I managed to capture just two photos without blemishes of rain. Beinn Alligin offered me no abundance of images. Yet that scarcity gave it weight. It demanded patience, reminding me that these summits are not easily captured, and these types of moments are the memories that will linger longest. The cloud dropped and gripped tightly on the mountains for the majority of the next day.

Beinn Eighe – 976m

This is the image that ended the stranglehold of cloud and rain. The end of the previous day, and much of the morning and afternoon, had been spent shrouded in low cloud, myself and the mountains both smothered.

Before arriving at this penultimate location, I had a formed a clear vision of what I wanted to capture. Most photographers (rightly so) tend to shoot the vast array of erratics that dominate this landscape, with the loch below acting as the natural progression to the mountain. But while scouring maps and conferring with satellite imagery, I noticed a river running from the loch’s mouth. This detail persisted in my mind. I walked its length, pausing to scout for rapids that would provide the right weight and energy to balance out the imposing cliffs.

I had timed my arrival perfectly. A reluctant shaft of light broke through, falling across the face of the mountain. It was a faint streak, but just enough to outline the ridges, emphasising its dominance. I knew which location I had to get to. This time there was no flustered running about in a panic, just a case of calmly hopping over the river back to this composition and making sure everything was in focus.

This was the most coherent scene on offer: rapids flowing in from the bottom right; complemented by evenly spaced boulders broken up by clumps of grass; all elements gently progressing towards the dominating Triple Buttress, holding the attention. After a day of silence and concealment, Beinn Eighe offered a single moment of clarity – the perseverance paying off.

Beinn a’ Chearcaill – 725m

Once the fleeting light on Beinn Eighe had faded, I boiled up a quick pot noodle by the river. It was then, almost absentmindedly, that I noticed a single, narrow strand of light sweeping across the landscape. Just ten metres downstream from the last vantage point – but facing in the opposite direction – Beinn a' Chearcaill was waiting.

I had already made one attempt at photographing this mountain during the frenzy of rainbows the previous day. In my haste, I forced two boulders into the foreground, creating an image with no purpose and no real connection.

It was the only time this mountain had presented itself and I was blinded by the rainbow, not putting any thought into the process. It was simply instinct. Ever since, I’d been quietly disappointed, rehearsing how I might explain the unimaginative result.

This sliver of light felt like a reprieve, a chance to correct my previous falter. By the fourth afternoon, fatigue had set in, yet this was the most alert I had been. Every other mountain was accounted for, but this one remained unresolved.

I worked quickly, centring the composition around a commanding boulder being held in an enclave of the river. All movement in the frame seemed to converge – lines of rock, water, and shadow – pulling the eye inexorably toward the light illuminating Beinn a Chearcaill.

A Dialogue with the Mountains

This photographic challenge shaped the trip, forcing me into a slower, more deliberate rhythm than my usual approach. At first, I found myself in a familiar cycle – racing from one composition to another, as if with tunnel vision. But along the way, that urgency gave way to patience and acceptance of the conditions. Shooting with an end goal in mind meant looking at scenes I might otherwise have ignored, noticing the quieter authority of the smaller peaks, often revealed with passing light.

These may not be the single “best” images I made in Torridon – due to the partial constraints of the challenge – but they feel like the truest representation of these mountains. Eight mountains in four days, each asserting its own character through light, weather, and form. Some demanded effort and persistence, others gave themselves generously, but all carried equal weight in shaping the story.

Presented chronologically, the images not only reflect the range’s often volatile microclimate, but also the shift in my own process – from hurried reaction to a more intentional dialogue with the landscape.

Issue 342

End frame: “Maple and Birch Trunk & Oak Leaves” by Eliot Porter

For as long as I have photographed ‘seriously’, I have been a fan of Eliot Porter, the American photographer. There are thousands of wonderful images in the numerous books he has published. I might, for example, have chosen one from the ground-breaking In Wildness is the Preservation of the World (1962) with quotations by Thoreau or the Glen Canyon portfolio (see later). But I chose this because it is a mysterious image and also because my wife and I are fortunate enough to own a signed dye transfer print of this image. In a room hung with many fine monochrome photographs, only this one is in colour. And what colour! There are the warm oak leaves of a New England Fall, lively greens, deep near-blacks, and the bright almost whites of trunks that flank the centre of the image.

Clearly, I am not alone in admiring this image, even here in Sheffield. In 2016, Adam Long chose this photograph in an end frame article, having seen it on the wall of a climber’s pub, whose walls were adorned with framed landscape photographs. Adam describes this as a ‘big print’, but the original is not big at all, just 34 x 27 cm, typical of Porter’s dye transfers. I’m not a fan of big prints.

Intimate Landscapes Cut from an Infinite Tapestry

It is sometimes said that a photograph should have a prominent point of interest. Camera club judges sometimes ask, “What am I supposed to be looking at?” as a way of criticizing images that do not have such a point of interest. But isn't that an arbitrary requirement like the so-called “rule of thirds"? Photographer John Wawrzonek thinks so. “In most images, I deliberately avoid a prominent point of interest. I want the viewer to explore the image and to see the wonders of the details of nature."

Wawrzonek is a master of the intimate landscape. Since the 1980's, he has been shooting colorful small scenes, images of ground cover, pond plants, reeds, and frost-covered foliage. He has also photographed larger scenes, but usually with no prominent point of interest. William Neill has called Wawrzonek “one of the greatest landscape photographers of our time.” In an "On Landscape" interview, Claude Fiddler said Wawrzonek was one of the two photographers who most influenced him. Yet Wawrzonek, who is now 84, is little-known.

I just recently discovered his work. I happened to pick up one of his photo books at a hiking lodge and was blown away by some of the images. Wanting to see and learn more, I purchased his books (used because they are out of print), looked for his website, and gave him a call.

Like Ansel Adams, music was John's first love. He came from a musical household, learned to play the piano by the age of eight, and accompanied his father, who played violin. By his teens, he was an audiophile. At MIT, where he studied electrical engineering, his faculty advisor, Amar Bose, offered him a job as employee number five at his startup audio equipment company, now the famous Bose Corporation. Making music and making recorded music sound good was a precursor to his next profession, taking photographs and making high quality prints.

In 1974, while working at Bose, John bought a 4x5 view camera. At first, he did some fairly conventional landscape photography on travels out West, large scenes, mountains, waterfalls, the usual stuff. "Two lessons emerged: you had to go often to the same place to be on site when something special was happening, usually with the weather, and you needed time to explore. This meant shooting close to home." He also wanted to chart his own path. "I didn’t want my images to look familiar, and that implied no lessons but rather experimentation.... I began without a clear idea of what I wanted to photograph, except that I did not want it to be the usual places, the recognizable iconic views predominately in the West."

While he deliberately did not study photography formally, John did attend exhibitions. In 1977, he went to Eliot Porter's "Intimate Landscapes" exhibit in New York. Porter's was the first solo exhibition of color photographs ever presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A pioneer in color photography, he was one of the earliest adopters of Kodachrome, the first widely available color film, and dye transfer printing, which had been developed in the 1930s for technicolor films. Many photographers at the time were skeptical of color, including Ansel Adams, who thought of it as purely realistic, not expressive.

Wawrzonek loved color and at the time he started shooting, dye transfer was the only way to print brilliant color and control contrast, saturation, and brightness. It was an extremely complex, labor intensive, and sensitive process, but with his technical background and the help of an assistant, John built his own print lab.

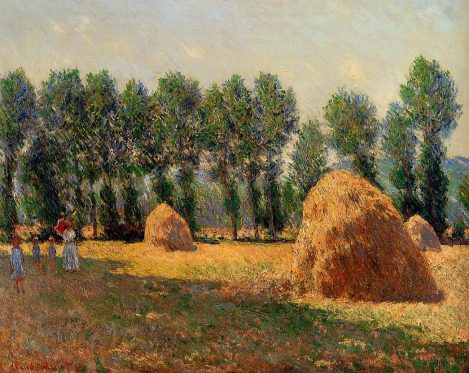

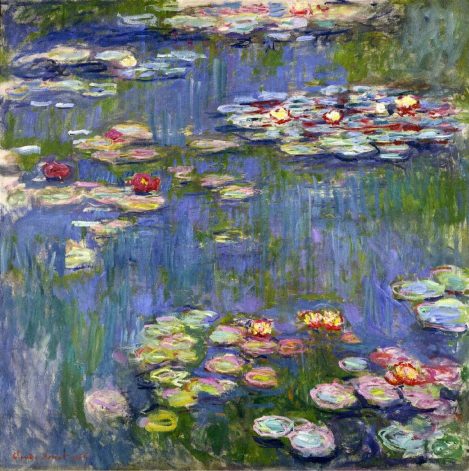

Another influence was Impressionist paintings. "I had attended every impressionist exhibit that came my way, but there was one, 'A Day In The Country', that was the show of shows." He especially liked the paintings of Claude Monet, the founder of Impressionism. Monet was famous for his many pictures of colourful lily ponds and haystacks. "Now I had an idea," writes Wawrzonek. "With a view camera on my back, the paintings of impressionists told me to look where other photographers had not, and to...let the nature of my New England home take me where it would. And it did."

Wawrzonek experienced a breakthrough one day in the Spring of 1981 when he discovered a particular view of some trees. "It happened that the only place to photograph these trees was from elevated portions of Interstate 90 a few miles west of Boston. This was a unique vantage point that placed me as high as the tree canopy as well as close enough to photograph. The trees in early spring became a pointillist ensemble of buds of various colors, some as brilliant as leaves in the fall."

"These images led me to seek other places and subjects where an ensemble of texture and color was the heart of the image.... I was amazed at what I found along major highways and ordinary roadsides. Without a distinct subject, the image often became something of a tapestry, seeming to extend without limits." This notion of a tapestry that extends without limits became a central feature of Wawrzonek's style. “Images contain a horizon only if it contributes to completing the composition. I also try to make the image extend without diminution from corner to corner, as if cut from an infinite tapestry.”

Eliot Porter had a similar idea he expressed in a different way. "Photography of nature tends to be either centripetal or centrifugal. In the former, all elements of the picture converge toward a central point of interest to which the eye is repeatedly drawn. The centrifugal photograph is a more lively composition, like a sunburst, in which the eye is drawn to the corners and edges of the picture: the observer is thereby forced to consider what the photographer excluded in his selection."

Not only intimate landscapes in general, but also this particular kind of image, a small scene that extends without limits, has become popular among photographers in recent years. In his focus on "infinite tapestry" and shooting locally at a time when large scenes in iconic locations were more in vogue, Wawrzonek was ahead of his time.

Another idea resonated with and reinforced Wawrzonek's interest in photographing locally, the notion of the "hidden nearby," which he derived from this passage in John Hansen Mitchell's book, "Ceremonial Time": "Wilderness and wildlife, history, life itself, for that matter, is something that takes place somewhere else, it seems. You must travel to witness it, you must get in your car in summer and go off to look at things which some ‘expert,’ such as the National Park Service, tells you is important or beautiful, or historic. In spite of their admitted grandeur, I find such well-documented places somewhat boring. What I prefer, and the thing that is the subject of this book, is that undiscovered country of the nearby, the secret world that lurks beyond the night windows and at the fringes of cultivated back yards.” This quote inspired Wawrzonek to write the following verse: “Out of the corner of my eye, in the ‘Hidden World of the Nearby,’ untended Gardens Thrive, Or pass from time Unnoticed.”

"The message of being aware," John writes, "being conscious of that which is nearby but hidden, is one of the most important guides to life as well as to photography. It took me over a decade of photographing to realize that I had to have an open mind, a mind without preconceptions, to see when I looked." Wawrzonek later used "The Hidden World of the Nearby" as the title of one of his exhibits.

Wawrzonek photographed throughout New England as well as the Great Smokey Mountains and further south, but some of his most memorable photography experiences were by the sides of nearby highways and roads, as well as at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts not far from where he lived, and in Acadia National Park in Maine.

Eliot Porter had used selections from Henry David Thoreau, famous for his sojourn at Walden Pond, in his 1962 Sierra Club photo book, "In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World". Decades later, colleagues of Wawrzonek's wife, who worked for the parks department, suggested that John photograph at Walden Pond. This led to eleven years shooting at and near Walden Pond and two books containing selections from Thoreau, "Walking" in 1994 and "The Illuminated Walden" in 2002. Thoreau's observations fit well with both photographers' attention to nature up close, as well as Wawrzonek's notion of the hidden nearby. Thoreau believed that beauty is often hidden in plain sight, concealed from us by inattention. We fail to notice not because nature is distant, but because we are not truly awake to it.

Nature will bear the closest inspection. She invites us to lay our eye level with her smallest leaf, and take an insect view of its plain. ~Henry David Thoreau, Journal, October 22, 1839

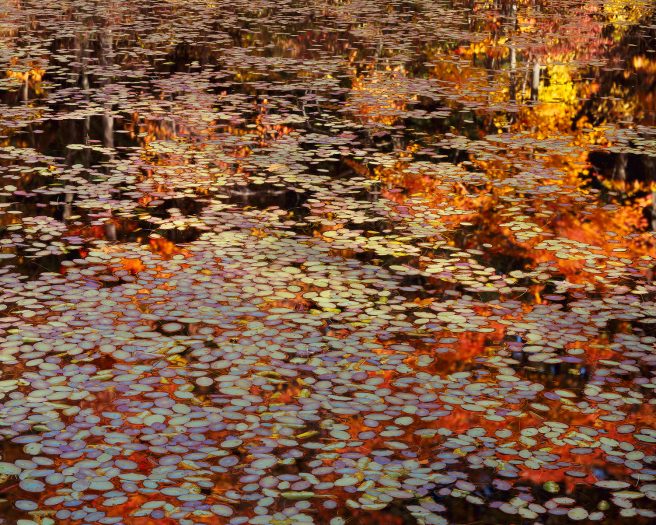

A particular meadow that Wawrzonek came upon near where Thoreau's cabin had been was a revelation. "When I stumbled on Wyman's Meadow, I went bananas." he says. What he found there was a vernal pond (a temporary shallow pool) with violet and green Water shields floating on the surface. Water shields resemble lilies but are actually a different species. Orange and yellow reflections from the sun and trees behind the pond added a beautiful glow complementing the water shields. Wawrzonek shot a whole box of sheet film that day. Although he returned many times over the next 10 years, those conditions never recurred.

Another vernal pond, Upper Hadlock Pond, beside a road in Acadia National Park in Maine, was also a favorite location. Wawrzonek discovered it on his first trip to Maine and visited it whenever he returned. It contained a patch of yellow, orange and green reeds that "has come to feel almost like family". It was windy on the day he found it. At first he was bothered by the wind, but then he realized the wind created "a kind of dance in which I participate." And on quiet days,"the reeds just line up to show their fall colors," reminding him of Monet’s haystacks.

Wawrzonek made very large prints of his Hadlock Pond photos showing the reeds in great detail. By the late '80s, he had gained a reputation for exceptional prints, and his print lab and gallery had become a successful business. Wawrzonek made much larger prints than were typical at the time. Unlike Porter, who considered prints larger than 16" x 20" to be wallpaper, John developed prints at sizes that were almost unheard of at the time. People told him they wouldn't sell, but they did. Over time, he sold prints to many hospitals, banks, corporations, and celebrities. In 1987, he printed and sold a portfolio of Porter's photographs chosen by Porter himself, sized 32" x 40".

When printing, Wawrzonek routinely made adjustments to contrast, saturation, and brightness. "This kind of manipulation is straightforward today," he writes, "but in 1983 when the photograph [below] was made, there was no Photoshop to fall back on, and so my reliance on dye transfer printing paid enormous dividends." In the example below, when shooting the image, he deliberately underexposed because he was photographing into the sun. When printing, he opened the shadows.

By 2005, Wawrzonek had switched entirely to digital photography and printing. After 30 years of landscape photography, he moved on, creating some outstanding floral work in his "infinite tapestry" style. Then, using Photoshop, he turned photographs of musical instruments into tapestries he called "lightsongs". In a sense, he was returning to his roots in music.

The days when people only saw a photographer's work as prints on a wall faded with the rise of the internet, and John began working on a website. But for years, it remained a sprawling work in progress, which may be one reason he is not well-known today.

John created another website as well, called "Caring For the Earth". His sensitivity to ecological and political crises goes back decades. Realizing that no effective action was being taken on climate change, he used this website to argue for wartime level investment in carbon capture along with an urgent effort to reduce emissions to zero. As an engineer who knows something about risk, he said, you plan for the worst case.

As time went on John came to feel that no one was listening, and the situation was hopeless. On top of that, Trump came to power. John had recognized the man for what he is back when Trump spread lies about Obama's birthplace. Now, as President, "Trump is showing us what he is made of. His poisonous brain is dismantling America. An insatiable longing for recognition, a monster who knows he is worthless...he will violate every legal and moral principle to get what he wants. If the Supreme Court does not stop him, it will be the end of America and possibly the destruction of the earth.... He will stop at nothing to fill the void that is his soul." John was talking here about the good old days of Trump's first term. But John was prescient. He knew what was coming. Sadly, this was enough to drive him into a very dark place, disturbing his sleep. His family worried and encouraged him to lay off the politics for his own good and return his attention to photography. He is now busy creating a new, simpler photography website.

If you'd like to get in touch with John for any prints or questions, please send John an email directly.

Water shields and Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts, October 1991 cat. 06321919

References

Bibliography

- John Wawrzonek, Walking: An Abridgement of the essay by Henry David Thoreau, The Nature Company, Berkeley, 1993

- John J. Wawrzonek, The Illuminated Walden: In the Footsteps of Thoreau, 2002, edited by Dr. Ronald A. Bosco, President, The Thoreau Society

- John Wawrzonek, The Hidden World of the Nearby: an unexpected intimacy, Images from the Exhibit at Olin College, Needham, Massachusetts, February-May, 2014

- Eliot Porter, Intimate Landscapes, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979

- Eliot Porter, "In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World," Sierra Club Books, 1962

- Video of and about Wawrzonek: an artist profile, cinematography by Claude Fiddler

- Juniper Haircap Moss, Wachusett Reservoir May 1994, cat. 4148

- Small-Singular Luminary, Ledges Trail, Baxter State Park, Maine October 1988 cat. 0265

- Untitled

- Haystacks at Giverny, Claude Monet

- Water Lillies, 1916 Claude Monet

- Peak Color

- Untitled

- Red Blueberry

- Water Shields and Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts October 1991, cat. 0632

- Wind and Water II (Upper Hadlock Pond)

- Upper Hadlock Pond Installation

- Spring Sunrise, Exit 11, Interstate 90, Millbury, Mass

- Melange Installation

- Untitled

- Stream with Rocks and Leaves, Cambridge, Vermont October 1977 cat. 0487

- Water-shields And Oak Leaves II, Wyman’s Meadow, Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord, Massachusetts, October 1991 cat. 06321919

- Lichens And Teaberry Leaves, Acadia National Park, Maine September 1990 cat. 0397

- Lightsong

Shelters

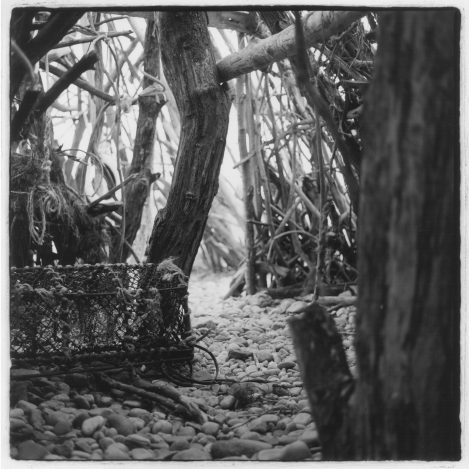

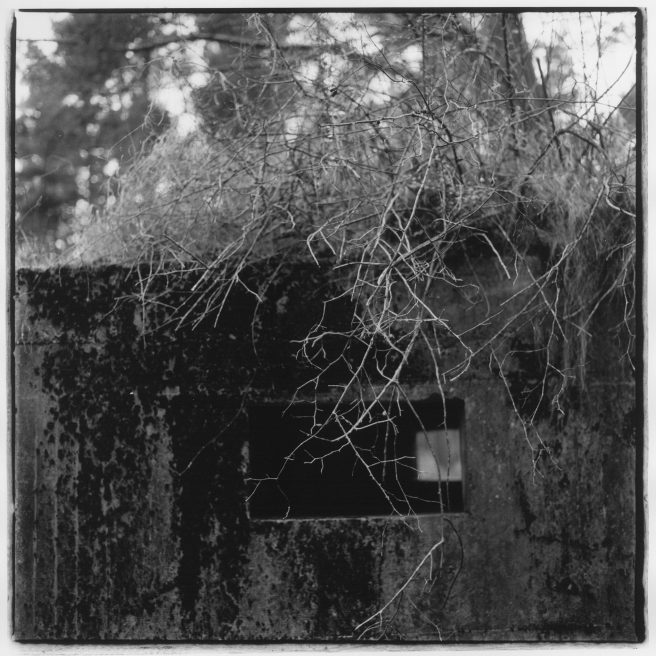

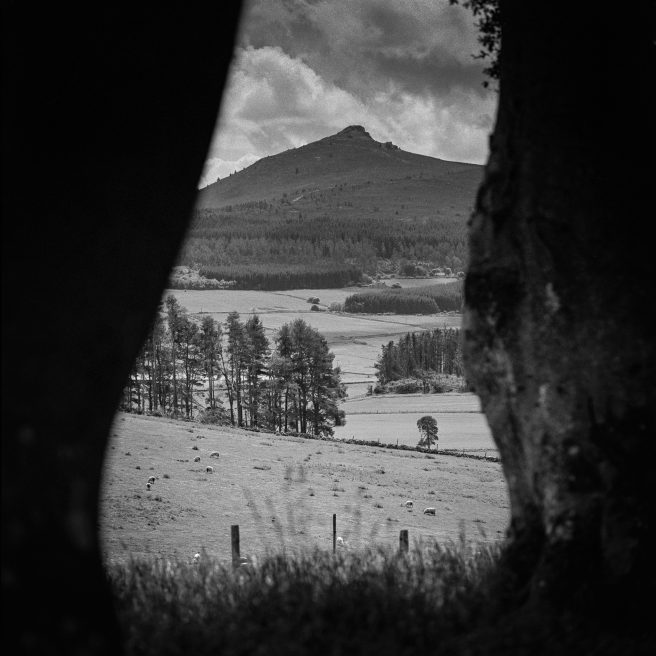

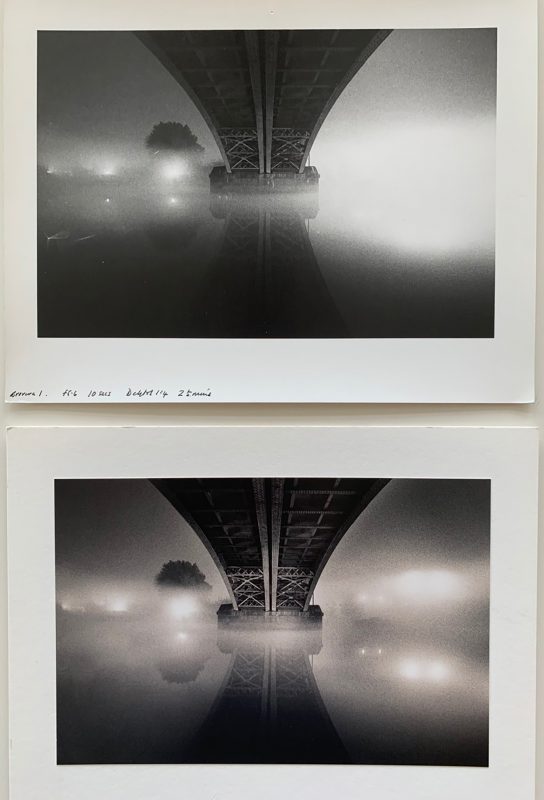

“Shelters” is a documentary series of photographs that examines the visual parallels between World War II sea defences on the Moray and East Highland Coast and a unique, man-made driftwood structure previously located at the mouth of the River Spey.

This project was first exhibited at Eden Court Theatre on the Flow Photofest Wall from July 20th to September 13th, 2025. Captured on film and hand-printed on silver gelatine fibre-based paper at the Inverness Darkroom, where I am a member, the exhibition presents two series of images in parallel. This comparison highlights surprising similarities in form and features between the robust military structures and the organic driftwood sculpture, despite their differing origins. A poignant meditation on the concept of refuge, the project explores how two very different types of "shelters" stand against the relentless forces of nature and time.

The Inspiration Behind "Shelters"

The inspiration for "Shelters" began in the Summer of 2024. I was taken to see a unique structure at the mouth of the River Spey at Garmouth, Moray: a massive beach hut, constructed from a collection of driftwood, boat pieces, and washed-up items. Built by a family during the COVID-19 lockdowns, the hut became a local community feature; a testament to the human desire to create refuge and find freedom in difficult times. In the bizarre driftwood structure, I saw the childhood dream of a fort or den, the kind I built as a child by placing broken branches on the ground to create rooms, and building the walls and roof with my imagination, but, instead, this was reality.

Just yards away from this organic creation, I discovered a crumbling World War II pillbox, slowly surrendering to the sea. This striking juxtaposition sparked an idea. I began to see connections between the two structures. Despite their different origins—one a military fortification and the other a communal gathering place—both were built to withstand a threat, and both were ultimately temporary. Standing on a coastline plagued by coastal erosion from the North Sea, both the pillbox and the driftwood hut were destined to give in to the same waves. This shared fate became the central theme of my project.

From Idea to Reality

With support from a Creative Scotland Visual Artists and Craft Makers Award (VACMA), I formally began the project in December 2024. I initially planned to use a 4x5 camera, but soon discovered the slow, deliberate process was not working for me. Instead, I turned to a Hasselblad 500cm. Although retaining the slow nature of film, it allowed me the freedom to work handheld in and around the structures.

My photography comes to life when I work with others, especially those who share my passion and drive for creativity.

We visited the beach hut on three occasions: 1st and 31st of December 2024, and 5th of January 2025. Over this period, the north of Scotland was battered by harsh winds as Storm Darragh raged across the UK. Over the course of five days, the waves slowly devoured the beach hut: on 31 December, half of the structure was in the water, and, by 5 January, nothing was left but debris. I chose not to show too much of this deterioration in the exhibition; I plan to work on that aspect of the project, going back out to the WWII structures featured to record changes and continue the story of erosion from the waves and the wind with a view to producing a zine or larger exhibition over the next year.

Capturing the Details

I find myself drawn to the details in a scene—the cracks in a wall, a small plant growing in a bizarre place. When I'm out shooting, I often start with a more traditional, wide landscape shot. But these images rarely resonate with me. It’s when I start moving around the scene and getting closer that I begin to see the compositions in my mind. My Hasselblad helps me frame these more intimate shots. Working with black and white film has allowed me to better understand and capture the way tones, shadows, and highlights shape a photograph.

When visiting the beach hut, I found myself drawn to capturing the layers of waste that had been used to build the walls and roof of the structure. In one of the images exhibited, I was attracted to a ‘Caution Busy Road’ sign that must have found its way to the shore.

From January to March 2025, I began visiting WW1 and WW2 sites along the Moray coast, photographing pillboxes near Garmouth, which I had discovered during my initial visit to the beach hut. Then the famous blocks and station points in the Lossiemouth woods, also captured by Marc Wilson , which were built by the exiled Polish Army Engineer Corps living in Scotland during the war . A radar station and a gun emplacement on Nigg Hill overlook the mouth of the Cromarty Firth. During both World Wars, the Cromarty Firth has had huge importance as one of Britain's deepest enclosed ports. WW1 housed the fleet, and WW2 served as a fuel depot . Shona and I also visited the famous, massive Inchindown fuel storage tanks, built into the hillside above Invergordon. This couldn't be included in the series, as unlike David Allen and Simon Riddell, I wasn't keen on taking my camera into the dark oil-covered tanks.

In the Darkroom

I started working with film in the late 2000s while studying Higher Photography at school, where I worked in a basic darkroom. As time moved on, I found myself exploring film again in 2021. I joined The Inverness Darkroom in 2022 and quickly transitioned from 35mm to 645, then to 6x6. Working with film has dramatically changed my practice. With only 12 images per roll of 120 film, every frame has to be carefully considered.

For this exhibition, I used Agfa Multigrade Fibre-based paper. The paper has a unique creamy base that gives my images a richness and depth that is often lost on other papers. I print using a Durst CLS 500 with negative carriers that have been filled out to enable the whole of the frame to be printed, showing the edges. Some view this as a photographer’s conceit; I view this as a challenge to get it right in camera.

The Exhibition

The first exhibition, which took place on the FLOW photofest wall at Eden Court Theatre, presents the two series in parallel, one above the other, inviting viewers to draw their own connections between these surprising and powerful “shelters.” Eden Court is the largest multi-arts venue in Scotland, based in Inverness, the capital of the Highlands. Since the inception of the project and arranging exhibition space, I have become more involved with Flow Photofest, becoming an intern of Flow.

What’s Next

I continue to explore the Moray and East Highland coast, documenting former World War I and II buildings, runways, and other military relics. The "Shelters" series is a compelling look at the visual echoes of our past and the fleeting nature of our present, all captured through the timeless art of film photography. The beach hut structure built during COVID has washed away, lost to time, except for the images captured by me and countless others who visited the coast.

Andrew Mielzynski

For this issue, we’re catching up with Andrew Mielzynski, the Natural Landscape Photography Awards’ Photographer of the Year 2024, and the International Landscape Photographer of the Year 2024. Andrew’s practice is rooted close to home in the varied landscapes of Ontario, Canada.

From capturing dynamic sports through street photography to seeking quiet contemplative scenes, Andrew has maintained his enthusiasm for being out with a camera in all weathers. His deliberate and thoughtful methodology often focuses on small, accessible vignettes which have proven to be a sound foundation for his internationally recognised portfolio.

Tell us a little about yourself, Andrew – where did you grow up, what early interests did you have, and what did you go on to do?

I grew up in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. My parents worked very hard, and my two brothers and I were extremely lucky to have a small cottage on Georgian Bay. The Bay is part of the Great Lakes that Canada and the U.S. share. Our cottage faced west, and the sunsets there are spectacular. My mother had a small film camera, and she loved to capture the light at the end of the day, but it wasn’t until a friend of the family showed up with his film Minolta that I really fell in love with photography. I was 12 years old, and our friend, Frank, set up the camera so all I had to do was press the shutter. I managed to make three photographs, and a couple of weeks later Frank showed up with three prints, one of a sunset, one of a couple of flying ducks and one of a frog. They were out of focus and nothing special, but I was amazed that I had made these, and I was hooked!!! I still have these incredible works of art. In those days, very few 12-year-olds had a camera, and I had to wait until I was finished university to buy my first film SLR, a Nikon FA.

Any Questions, with special guest Simon Baxter

The premise of our podcast is loosely based on Radio Four's “Any Questions.” Joe Cornish (or Mark Littlejohn) and I (Tim Parkin) invite a special guest to each show and solicit questions from our subscribers.

In this episode, Tim Parkin talks to Simon Baxter and Joe Cornish about the intricate relationship between mindset, expectations, and the art of woodland photography. All the more relevant because of a new exhibition and book Joe and Simon have produced called "All the Woods a Stage".

Read more:

- About insights into their exhibition in an article they wrote for On Landscape, "All the Wood's a Stage"

- Exhibition details

- Exhibiton book "All the Wood's a Stage" available to buy

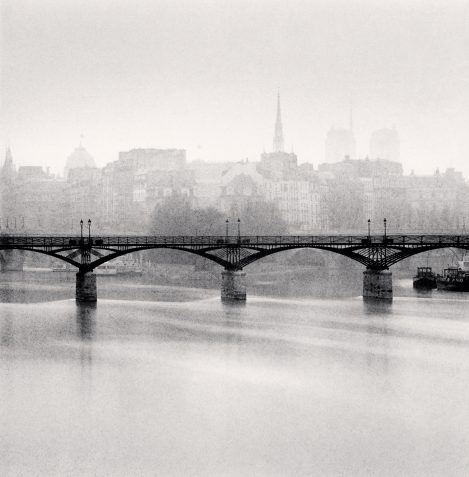

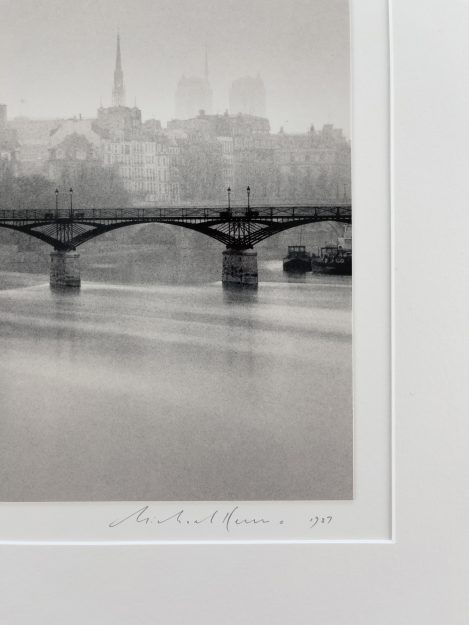

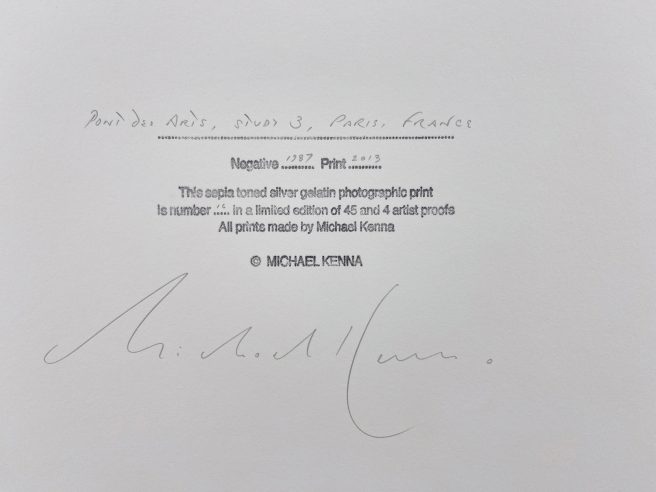

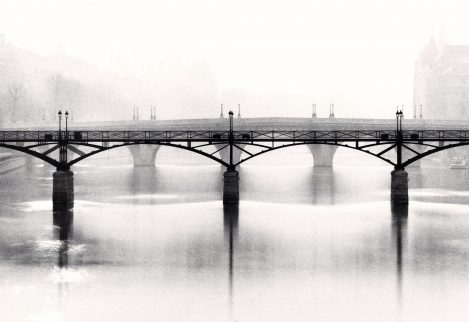

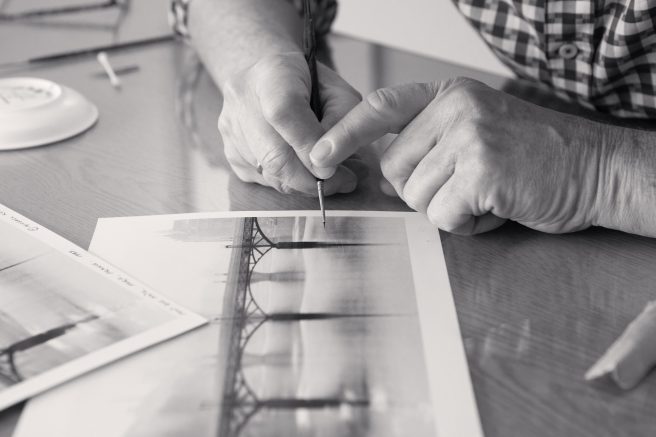

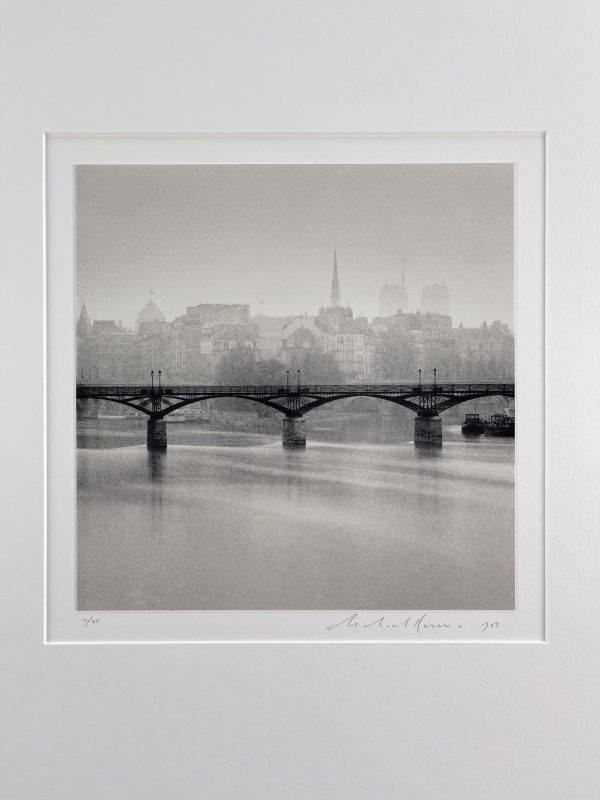

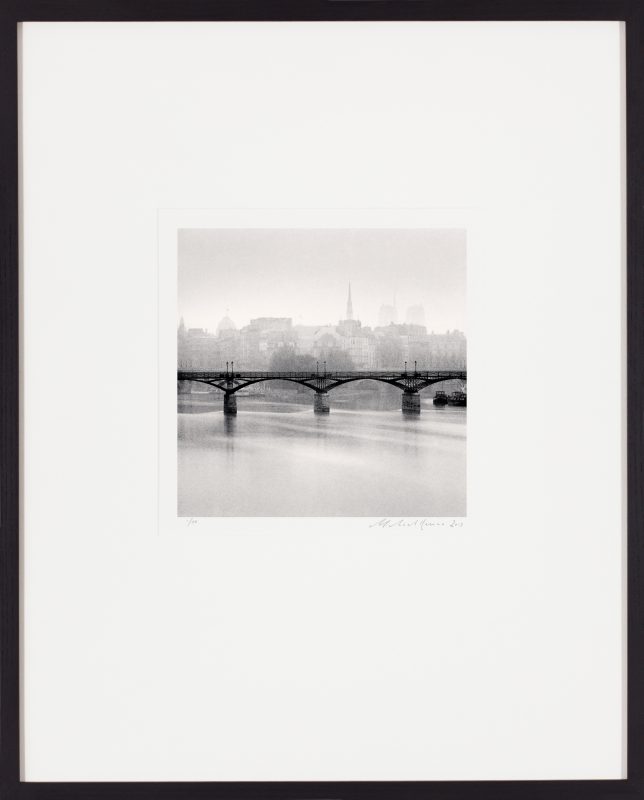

Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries

In the final of five chapters serialising Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries, Michael explains how his prints are mounted, matted, signed, numbered, dated and framed.

Read the previous articles in this series:

- Chapter 1: Working With Film For Over 50 Years

- Chapter 2: Printing in the Darkroom

- Chapter 3: Grain, Cropping and Toning

- Chapter 4: Chapter 4: Retouching Prints By Hand

Luke Whitaker