End frame: The Pond Moonrise by Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen (1879-1973) had a hugely varied and influential life as a painter, photographer and later, curator. His early career straddled an era when serious photography was trying to work out its own identity, still deeply influenced by art yet simultaneously trying to break free. It could be argued that The Pond – Moonlight (1904), taken in Mamaroneck, New York, near the home of his friend Charles Caffin, still stands as his most important early work. I would argue that this is not because of how it is valued in modern society – in 2006, one of three known prints sold for $2.9 million at Sotheby’s, at the time, the record for the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction. However, for me personally, as a wildlife and occasional landscape photographer, there is something much more interesting going on.

At first glance, when we look closely, we have a woodland scene reflected in a pond, a washed out blue sky as backdrop and the moon just rising beyond the trees. There is colour here, but muted and the near foreground appears indistinct as if Edward had taken a paintbrush to the reflection and swished them to a blur. Above all, there is the feeling that if this is a photograph, it is going through an identity crisis – am I a reflection of reality or am I reaching towards art?

This is, in essence, a great work of the Pictorialist movement, which desired above all else to move away from realistic depiction, from recording an image, to creating something out of that image. Generally, Pictorialist images are slightly unfocused, dreamy, printed in more than one colour and may even involve brush strokes or other interventions.

Jeannet van der Knijff

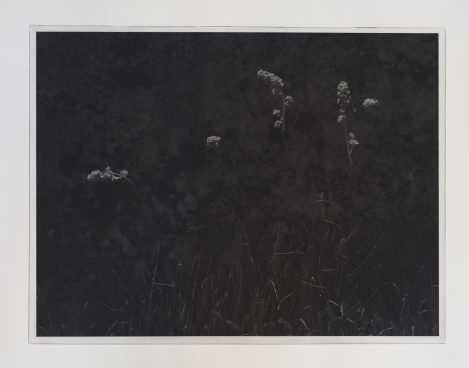

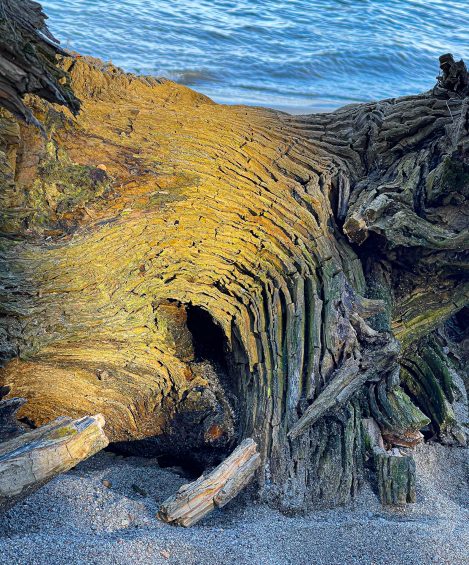

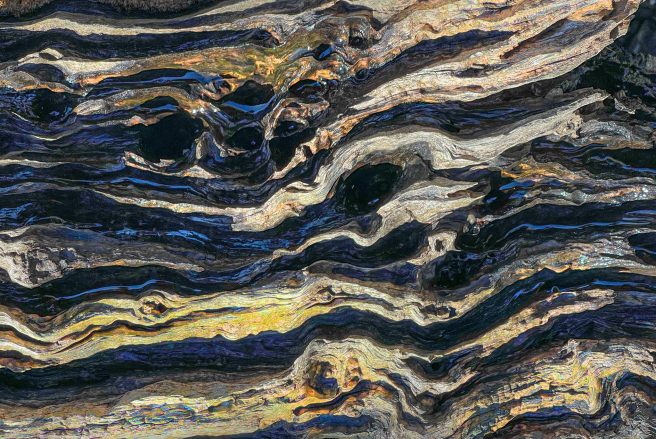

Landscape is a human construct, a surface on which we impose our own view of what is worthy of photographing, what is natural or not, and what belongs to other genres (nature/wildlife, etc). If you look long and closely enough, the lines blur. Welcome to the world of the small, which turns out to be very big.

It’s not often when researching these interviews that I can select 16 images from the last twelve months, but in Jeannet’s case, we could have done exactly that. Intimate, at times abstract, they demonstrate a watchful noticing and a keen eye for serendipitous juxtapositions. She delights in the ephemeral, in rain, in the ordinary, which, if you look closely enough, is anything but.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself – where you grew up, what your early interests were, and what you went on to do?

I was born and raised in Hoek van Holland, a small coastal town near Rotterdam in the southwest of the Netherlands. I lived - very typically Dutch - in the polder, surrounded by meadows and next to a windmill. My father was a miller, and as such, he was responsible for regulating the water levels in the polder.

Any Questions, with special guest Paul Kenny

The premise of our podcast is loosely based on Radio Four's “Any Questions.” Mark Littlehjohn (or Joe Cornish) and I (Tim Parkin) invite a special guest to each show and solicit questions from our subscribers.

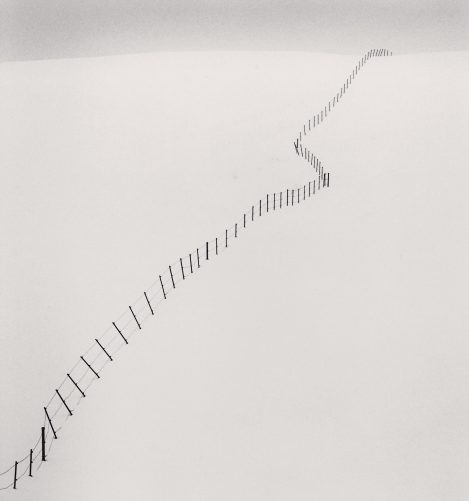

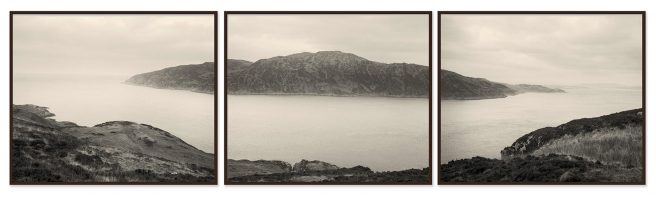

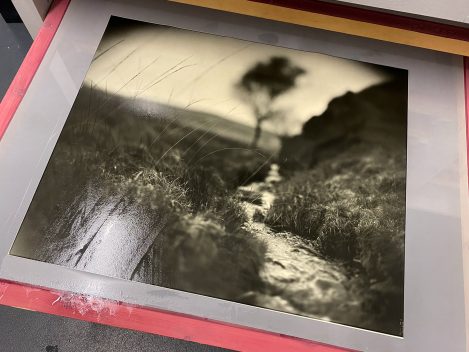

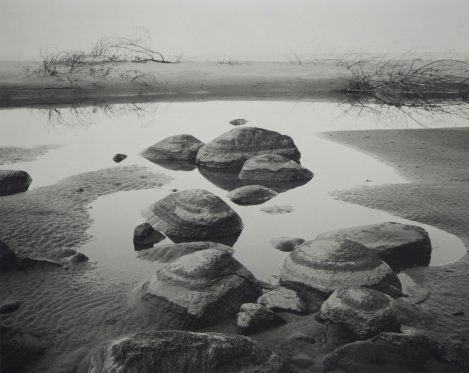

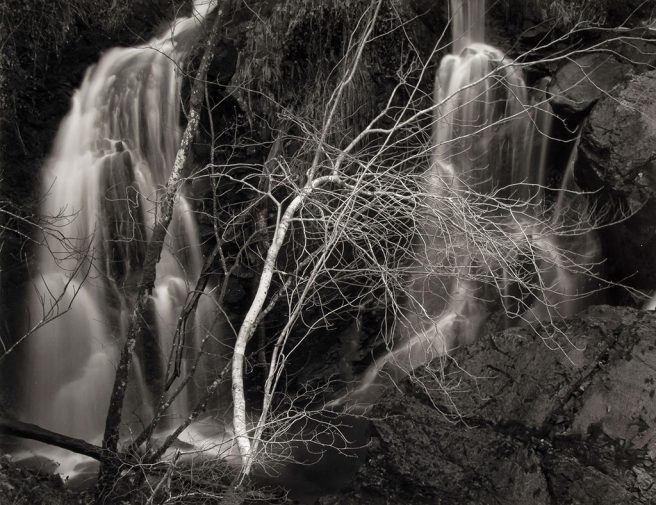

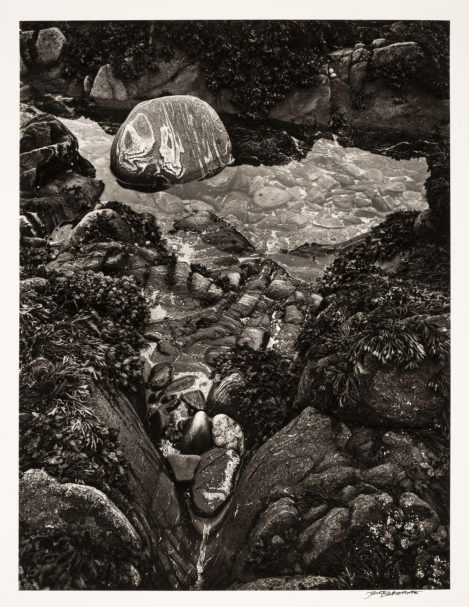

Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries: Part 1

Michael Kenna has been photographing on film and making silver gelatin prints in his own darkroom for over 50 years. In the first of a series of five chapters sharing extracts from Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries, we are reminded why prints made in the traditional analogue process, printed from original film negatives by hand in the darkroom, are so special.

Michael will discuss his process of photographing on film and will explain the patient and painstaking work of making prints by hand in his darkroom which has allowed him to produce the distinct images that are celebrated for their rich blacks, luminous highlights and a grainy aesthetic that compliments the ethereal lighting his work is best known for.

Luke Whitaker

I have been photographing on film since I started photography in the 1970s. For the first fifteen or so years I photographed with 35mm film, for the most part. Now, for over thirty-five years I have been using 120mm medium format film using Hasselblad cameras with various focal length lenses. Each film stock, with the various different darkroom chemistry combinations available, has the potential to give quite different possibilities. It is a hands-on affair to achieve a unique silver print, and I believe that making a print from film is different from printing a digital image from the computer. In my humble opinion, silver prints stand out for their unique and exquisite beauty. I love them.

After a typical two-week photographic trip, I will usually have over a hundred rolls of film to process. Each roll contains up to twelve exposures. Maybe I will go through five hundred to a thousand rolls in a single year. Multiply that by the years I have been photographing and the result is a potential storage nightmare! Fortunately, I have used a consistent method of filing since the beginning.

A contact sheet of every developed film is immediately made and filed with their respective negatives in binders. The year is marked on every binder with a list of countries photographed in. At this point, I have countless thousands of negatives filed by this system and can rapidly access them when needed.

I have always been enamored by the silver gelatin printing process, ever since I first started on my photography journey. Along the way, I have printed for several other photographers and learned various different techniques from their experience. However, it was not until I worked for Ruth Bernhard in the late seventies that I began to have the confidence to print some of my own more difficult negatives.

I think there is something very special about staying faithful to the original analogue process of capturing an image on film and making silver prints with wet chemistry. It can certainly be a time consuming and complicated process, but ultimately very rewarding as the photographer is involved in the process from beginning to end, and able to retain so much creative control and freedom.

Unlike many photographers, who use large format cameras, it is important to me that there is some grain in the image, which I regard as part of the language of photography, almost like brushstrokes on a painting. The 120mm format seems to me to be ideal.

In the past, certainly into the 1980s, when I was still working with 35mm film, I would make work prints (soft, dark and full frame) of any images that I considered interesting. I had many boxes of these, which I eventually donated as part of my archive to the Médiathèque du Patrimoine et de la Photographie, (MPP) in France. The work prints were my first stage of editing. I think objectivity happens over time. The longer I wait between photographing and printing, the more objective I can become. Over time, many of the subjective feelings and memories associated with what I was photographing begin to dissolve and dissipate. There are pros and cons to this. However, I think time is the true test of quality, and stronger images retain their fascination, whereas weaker ones fall away. I have found this method of image selection to be an economical and expedient way of editing in order to get to the few more interesting images that will eventually be printed. I must point out the personal nature of this method. A photographer such as Brett Weston might photograph, develop and print all in one day. A very different approach, and certainly equally relevant.

The 120mm format is bigger than 35mm, and since switching to that format in the mid-eighties, rather than make work prints I have found it more efficient to make two contact sheets of each developed film. The first is filed with the negatives, the second is cut up. Any of the contact size images that I think have potential for future printing have been put into albums. As with the work prints, I go over the albums from time to time and choose the images, which I will later print. As a point of reference, I would estimate that the ratio of photographs made to negatives being printed is approximately a hundred to one. Given the number of photographs I have made over the years, I think that if I gave up photographing today, I would have enough interesting negatives to print for the rest of my life!

I am often asked how and why I choose particular negatives to print, and I do not have a concise answer. Often, I work on particular projects over many years. There usually comes a time when the project reaches fruition in the form of a book or exhibition. I will then choose the strongest images to print. Why does one image appeal to me more than another? It could be something in the composition, light, or subject matter. There has to be an appeal, a resonance, a connection but I have never found it possible to articulate the exact ingredients of what is in the equation. In retrospect I think that is a good thing, as consciously or unconsciously I would begin to look for that ‘winning’ formula when photographing. The result might be repetition and inevitable diminishment of creativity. When photographing I try to do the opposite, I attempt to forget what I have just photographed. The silver process greatly assists me in this regard as there is no instant gratification. I never know what is on the negative until it is developed, and this encourages me to keep exploring and photographing. This important element of unpredictability is one of many aspects of the silver analogue process which I appreciate greatly.

Photography has often been considered one of the more accessible art forms. Like haiku poetry, it is relatively easy to do, but not necessarily easy to do well. These days, photography is readily available and accessible with little or no training needed. Most of us have digital cameras, often located conveniently in our phones, and there are countless apps for editing them. Thousands of images can be, and are, viewed online, often for seconds at a time. So, before we spend hours in the darkroom, perhaps we might take a moment to consider why we would even consider attempting such a time-consuming pastime.

Our five-sense physical reality involves faculties of sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. I am very well aware that in the darkroom I reduce this highly complex and colourful world to a frozen, silent, two-dimensional rectangle with lines, shapes and monochromatic tonalities. I then have the temerity and presumption to expect viewers to respond with interest. I even consider that they might even collect my prints! I have asked myself why, and as in many aspects of life, I don’t have the answer. But, I will say that from the first time I made silver prints, in a school bathroom sink, the magic and power of this process astonished me and continues to do so. I may not fully understand why a silver print can be so beautiful and inspiring, but my experience tells me that it is true. Hence, I have my own precious collection of silver prints made by other photographers that I admire and respect.”

Retired Negatives by Michael Kenna

Retired Negatives by Michael Kenna is an online exhibition of his most collected work over the past 50 years, featuring the remaining Artist Proof editions of photographs whose numbered limited editions have now sold out.

The collection is a chance to acquire a print from editions in which the negative has been formally retired within Michael’s archive. All of his silver gelatin prints are still made by him personally in his darkroom at his home in Seattle. The online exhibition is hosted by Bosham Gallery and can be seen at boshamgallery.com until 17th December 2025.

‘Machine-made pigment prints are of excellent quality, but, at least for me, silver prints remain the gold standard in photography,’ says Michael. ‘It is also comforting to know that these prints are made to archival standards, which means they should well outlast myself and collectors. I keep records of every print I have signed and editioned and have prints in my own collection which I made 50 years ago. They are as good today as when I first made them.’

To accompany Retired Negatives, and to celebrate 50 years of darkroom printing, Bosham Gallery’s Luke Whitaker is presenting a five-part series of chapters from Michael Kenna’s Darkroom Diaries.

Please visit boshamgallery.com to see the online exhibition.

Author image: Michael Kenna Photographed in 2011 by Song Xiangyang © All Rights Reserved

Personal Photography

There is the heart and the mind, the Puritan idea is that the mind must be master. I think the heart should be master and the mind should be the tool and servant of the heart. The man who wants to produce art must have the emotional side first, and this must be reinforced by the practical. ~Robert Henri

Photography is a technology based medium produced by a technological society with a reason-focused worldview. It contains two temptations: decoration and propaganda. However, I propose an attitude that promotes expression. You may or may not agree with me in the end, but if you consider the relationship between your thoughts, values, and attitudes toward photography you may gain something.

What is your relationship with your photographic material?

The Scottish Philosopher John Macmurry struggled with a similar question: what is our relationship with life? As a consequence, he offered a Philosophy of the Personal that I believe offers insights for photographers.

His most fundamental claim is that we should reject “I think” and substitute “I do.” If the “Self” is the “Mind” then it must be a substance or organism. If instead the “Self” is an “Agent” then it is personal and only exists in dynamic relation with the “Other.”.

This is radical when compared to typical Western philosophical tradition and the modern emphasis on rational choice, process oriented business, and law based society; all which operate like machines.

Agency and relationship are the basis of the “Personal,” including our relationship with nature. “I think” is a special case of action where the “Action” is only mental. Most of the time, we are acting with the support of thinking.

The neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist researches the role that the left and right brain hemispheres play, and demonstrates a more complicated relationship between an intuitive function and an analytical function that are highly integrated.

The artist, the philosopher, and the scientist all reach similar conclusions: the modern dualism of the Cogito misrepresents the complexity of humans.

Of course, the poet also has an opinion:

The Waking

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me; so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

Theodore Roethke

We think by feeling and doing. The lowly worm climbs because nature has a thing to do. All these speak to action, feeling, and intuition. The certainty of the thinking mind is nowhere present in the paradox of living.

What the philosophy of Macmurry brings to the table is a framework with three types of the “Personal:” Science, Art, and Religion, clarifying the nature of Art and the relationship it implies.

Science considers relationships between “things:” abstraction, the world of cause and effect, prediction, and control. Science produces “knowledge about.”

Art is a relation between an “I” and an “Other:” a concrete other; imagine standing before a specific tree in friendship, with a giving and receiving. Art produces “knowledge of.”

Religion is a relation between people, which I will neglect. My interest is Art and how it is different from Science and what a personal relationship based art means for photography.

Personal Photography finds The Waking by rejecting the modern focus on thinking, analysing, knowing about, and instead focusing on doing, feeling, intuiting: a deep, intimate knowing of, a closeness.

(Pre)-Visualization

For me this is the elephant in the room because it is highly promoted in some photographic circles, but it does not work for me. I don’t mean it can’t produce a good image, I mean I hate doing it and it led me to a search for an art philosophy that could explain what I actually enjoy doing.

My relationship with the landscape and nature was well established long before I had a camera. I grew up outdoors: cycling, hiking, fishing, and backpacking. Sitting still and just looking was something one did when taking a break, eating lunch, or waiting for the sun to go down so you can sleep.

Once I took a camera into the woods, I had a dilemma: how am I going to spend so much time looking and imagining some phantom image that will appear on a computer screen indoors next week, when all I want to do is move and explore?

Relationship First

My way out of this closet was to decide: I must ignore all the current advice about how to make good landscape images and put my relationship with the landscape first. I needed to be myself. Macmurry provided the assurance that I was not crazy and granted permission to ignore the gurus. Even though it might seem silly for a grown man to need these crutches, rejecting advice of well known peers is not always easy.

But now what? How do I take this longing for relationship and turn it into a photograph?

The Impersonal and Antipersonal

Before diving deeper into what a relationship oriented (personal) photography (art) implies, I want to put the “Personal” into a larger context than Macmurray.

Macmurry made a distinction between society and community, which gave me a clue for describing this larger context. Society is the mass version of community, impersonal and based on rules rather than community based on love. Community is the purest form of Religion, but it cannot scale to the size of nations. Art and Science also have Impersonal forms. The Antipersonal form completes the map.

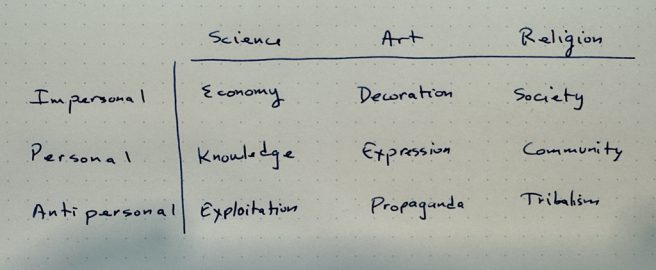

My conceptional model is as follows: Economy (Science), Decoration (Art), Society (Religion) are the impersonal forms; Knowledge (Science), Expression (Art), Community (Religion) are the personal forms; Exploitation (Science), Propaganda (Art), Tribalism (Religion) are the antipersonal, parasitic, or maladaptive forms.

Personal Art, or photography in the present case, sits between decoration/propaganda and knowledge/community. If photography avoids the impersonal and antipersonal it must avoid decoration and propaganda as well as avoid economy, society, exploitation, and tribalism. However, it may rely on knowledge and community for help.

This is an idealized model, so I don’t want to imply it is the only valid approach to photography nor that the box contents contain perfect words. My only claim is that I find this a useful model for understanding and guiding my approach, which aims for Expression.

The model puts Expression into a context for you to explore what it entails by exclusion. For Expression itself, I turn to phenomenology and surrealism for insight.

Phenomenology

We need to address another elephant in the room, that is our worldview, our culture, our knowledge, that baggage we carry around in our heads that affects how we see and pulls us away from Expression.

From the perspective of the Personal Art relationship, the relation between you and nature, baggage is a barrier to Expression. Who has not been in a love relationship with another person and found their family beliefs about roles, or their church’s teaching about authority, or their culture’s current beliefs about how to be together, have gotten in the way? Do we not carry a whole suitcase of cultural into the woods?

No ideas but in things. ~William Carlos Williams

Phenomenology suggests we can give all this stuff the boot and see what is really there. By extension, we can act on what is “actually there” and we can personally relate to what is ‘actually there.” This implies our personal relationship with the landscape and nature is not a threesome. (For “actual,” think Critical Realism)

Henri Bortoft’s “The Wholeness of Nature” is an entry point to a major promoter of phenomenology.

Goethe did not examine the phenomenon intellectually, but rather tried to visualize the phenomenon in his mind in a sensory way—by the process which he called “exact sensorial imagination” (exakte sinnliche Phantasie). Goethe’s way of thinking is concrete, not abstract, and can be described as one of dwelling in the phenomenon

Macmurry describes the art relation as “I” and “Other,” where the “Other” is concrete: that rock, not all rocks, this tree, not trees in general. This sounds similar to Bortoft and Goethe. Theory, language, the analytical, are all made secondary or deemphasized. Bortoft says:

Working with mental images activates a different mode of consciousness which is holistic and intuitive.

He states that our mode of consciousness is either analytical or intuitive. (This sounds a lot like left/right hemispheres described by McGilchrist.) He continues:

The purpose is to develop an organ of perception which can deepen our contact with the phenomenon in a way that is impossible by simply having thoughts about it and working over it with the intellectual mind.

This intuitive mode of consciousness is not scientific and is the essence of art and photography. However, we live in a society that on a good day glorifies science and economy, and on a bad day drifts into exploitation. We can also easily drift into decoration and other forms of commercial art or into propaganda and political art. These may be legitimate forms of photography, but I don’t consider them fully expressive because the artifact becomes an “end” in itself.

Surrealism

The intent of phenomenology goes beyond Macmurray in the sense that one is so engrossed in the other that not only does the analytical mode become inactive, the self might very well efface. What might surrealism contribute to understanding Expression?

André Breton wanted to neuter the “critical faculties:”

...a monologue spoken as rapidly as possible without any intervention on the part of the critical faculties, a monologue consequently unencumbered by the slightest inhibition and which was, as closely as possible, akin to spoken thought.

Breton was influenced by Freud and the trauma of WWI. He was promoting expression of the subconscious disconnected from external reality. However, Yvan Goll looked for grounding:

Reality is the basis of all great things. Without it no life, no substance. The reality is the ground under our feet and the sky on top of the head...Everything the artist creates has its starting point in nature...This transposition of reality into a higher (artistic) plane constitutes Surrealism.

Goll is grounded in experience but wants to transpose reality into something else. Breton focuses on the interior self and Goll focuses on the transcendent other. Breton releases hidden forces, Goll extends reality. Both suppress the critical facility, but neither focus on relationship as primary. These poles are found today in various ideas such as “abstract images representing emotion” or images with a “what else” it is.

What the “Personal” implies is an active relationship based on intuition, not the subconscious or unconscious, not dreams, not analytical thinking, not objective reality.

The photograph is a product of relationship, not the self alone, not the other alone, a relationship between a self and an other, rooted in the action of the photographer. constitutes Surrealism.

My Approach to Personal Photography

I don’t want propose a universal field approach; I will simply describe my practice and how I conceptualize my non-conceptual method. If you buy into the concepts and model I have presented, you will have to derive your own practice from them.

The key element of my process is walking, whether in a park or town, the woods, backpacking, etc. I do not drive somewhere and photograph from the road. I do not setup a tripod at a planned location and wait for sunrise or sunset. My planning goes no further than which canyon I chose to wander in and what kind of weather and season seems interesting.

Walking breaks down my analytical thinking mode, especially when hiking, when getting tired, especially in bad weather, and supremely out in nature. As I walk, because I have been a hiker for fifty years, I can allow my attention to drift off the trail and into the landscape in an intuitive mode without tripping and falling. I simply keep walking and keep looking until some feeling grabs my attention.

Then I stop and “actively” contemplate. Does the feeling persist? What if I move left/right, does the feeling increase? I call this feeling “resonance” because the feeling comes from the relationship I have with what is before me. Resonance occurs between me and other, it is not me alone, as if what I behold is remote.

If the resonance is strong, only then do I remove my pack and take out my camera. I might pack the camera up, walk 10 meters only to stop and take it out again. I do not walk with the camera in hand because it is a temptation to shoot too soon.

Once the camera is out, I start with a 70-200mm zoom most of the time. I zoom in/out, move the camera up/down/left/right, twiddle exposure and depth of field. Maybe make some test shots. I am sensing resonance as I move around seeking for the peak.

At peak I make the final capture.

If the resonance dissipates I pack up and continue walking. If I start analyzing, I put the camera away. When I don’t move on, I usually have frustration or poor results.

Note: I am not composing. I am not using rules. I only work by intuition and feeling.

My digital darkroom process follows the same principles of seeking resonance. I cannot walk and process, so I try to get into a flow state by removing all distractions. If I lose flow, I put the computer down and come back later. Working outside flow also produces frustration or poor results.

Pulling Personal Photography All Together

I will try to summarize with three points that are easy to remember:

- Intuition not Analysis

- Action not Visualization

- Resonance not Composition

Clearly, this is not a means to pleasing other people, it is not a means to win competitions, and certainly is not a means to profit. It is more like participation: an art life; a personal life in photography.

Expressions are a byproduct of personal relationships, not an end in themselves.

From Across the Ravine

This springtime in the Southeastern U.S., I felt a vivid sense of invigoration and motivation almost every time I visited the woods of a nearby mountain. Despite the constant distractions of a restless news cycle, I felt more attuned to nature's rhythms this year. In late April, I was very glad to receive a gentle reminder of a simple lesson nature had taught me years ago, when I tended to be more receptive to such things: that the beauty of life, in all its complex and varied forms, tends to show up in unexpectedly simple ways.

Our forests here in the Tennessee-Georgia mountains are chaotic and tricky to navigate, both physically and creatively, with a camera. Brambles, deadfall, saplings, vines and other havoc form the understory of the woodlands I enjoy, but every so often, standing above the mess, a new friend waves hello and asks for my attention. I have learned to heed these silent gestures—not just for the nice images they sometimes yield, but also for the relationships they can help build. Attention almost always develops into intention.

The quiet waves are a welcome sight, as modern life has a way of keeping my mind wrestling with itself over mundane things like politics, job stresses and (perhaps not so mundanely) the reconciliation of my personal values with the beliefs of some of the people I am close to. Contrasting strongly against the noise and tedium of the manufactured world, I’ve found the forest to be full of warm welcome, and I’ll gladly accept a humble “hello” from a stationary stranger on my dark days.

It was from a winding, apprehensive inner life, combined with the physically painful tangles of vines and thorns in these woodlands, that I found myself happy to rest in the shade of a newly grown light-green canopy, setting down my backpack and allowing my heart to slow after hiking up a steep hill. The reason I’d stopped wasn't to shed a layer or to take a pee; it was because someone, not a person, had waved at me and it would have felt rude to keep hiking.

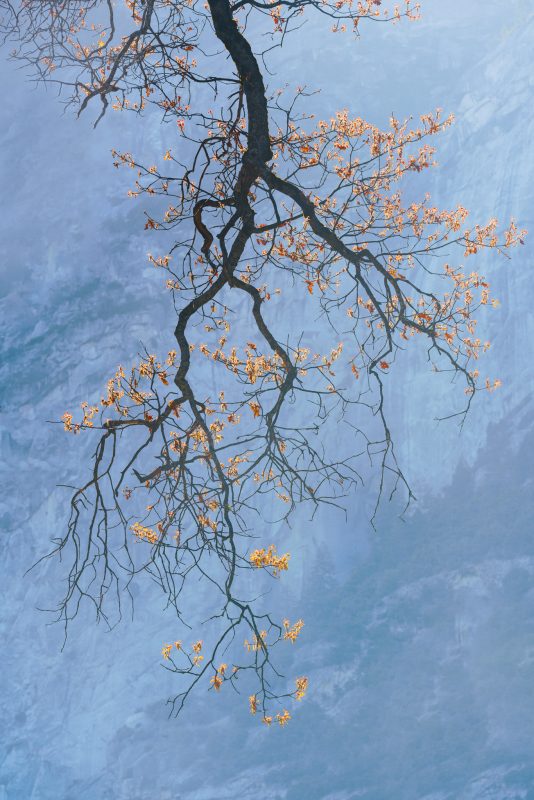

On this partly cloudy day in Spring, a tree’s slender arms formed countless Vs and Ys as it stood out against the darkness of the forest. It drew my attention from across a steep, cluttered ravine, just as thin clouds passed overhead and my breath rose and fell loudly in my head. The shifting light revealed textures of cracked bark that had been concealed in shadow on previous visits. Relief caught my eye, and a different kind of relief washed over me. It was time to go make an introduction.

I crossed the dark gully through several thickets of blackberry, earning a few new holes in my old T-shirt. Tucked between the chest-high branches of briars, I found slippery footing among embedded boulders still plastered with brown, decomposed leaves from the winter, as well as saturated lichen. I pictured a video game character hopping between rounded platforms in a sea of lava, but the going wasn’t exactly fun or exciting. A few choice words crossed my lips, but I managed to slowly negotiate the cluster without dampening my enthusiasm.

Finally, having reached the beckoning giant, I set down my camera bag and stood still, finding it surprisingly easy to ignore my ruminations and mental chatter. A quiet gratitude began to warm inside me as my breathing settled. I silently thanked the new oak for sharing its space—away from the chaotic, nagging thorns that had slowed my approach, and for the emotional distance it offered from lingering motivational setbacks, negative self-talk, and ever-present imposter syndrome.

“Reawakening”, Late Spring 2025 - A newer friendship realized just a few weeks later, after three years exploring its mountainside home.

The tree had an impressive yet unassuming presence, quietly overtaking my sense of purpose. Not a giant, nor a dwarf—just somewhere in between, ordinary in most ways. Looking upward, I realized I stood too close to frame a worthy portrait, but I reached out to touch the old oak with my hand, red with new scratches, out of respect. It would have felt too rushed and transactional to photograph it right away, to force a superficial relationship, without proper introduction.

This was the first sweat I’d felt while visiting here since early Autumn, and the new humidity caused my clothes to stick to my skin. As the forest thickened with even more undergrowth in the coming weeks, sweat would become a real hindrance to my mood and motivation. This place would inevitably fill with ticks, snakes, and hornets—creatures best avoided until the cooler temperatures of Fall drive them into the forest floor. Today, thankfully, shade worked alongside a generous breeze to cool my thoughts and emotions. It would be good to make some photos with help from my new buddy—this oak, who I realized in fact had secretly watched me walk past a dozen times already. We had just met, at last, and our next encounter couldn’t be guaranteed here on the edge of approaching Summer.

Clouds couldn’t be seen through the canopy, but I knew many passed overhead because of their effect on the trunk and appendages. Sunlight transitioned noticeably from extremely bright and spotted to boring, dark, and flat. Somewhere in between, the curve of the trunk and angles of the branches were afforded some dimension by waves of diffused, directional light.

Eventually we got there, working together between the clouds, to make something where once there was nothing. Nothing, only in the sense that my time with this oak did not exist before that day, and we never had anything to share with each other. I decided on an aspect ratio that honored the balance I discovered among its many branches. I turned the focus ring on my lens to crispen the oak’s torso, while I allowed some of its branches, and the background plantlife, to slightly blur. This seemed to align with my experience of our first meeting, when I was catching my breath and could only see clearly a short distance ahead. Then, I gave my polarizing filter a last experimental twist to help decide how much shine, if any, the thousands of lime green leaves should impart to my camera’s sensor.

Perfect light came and went gently and, with the shutter finally released, I knew the relationship bridge between me and the one who waved had been crossed. My brief time with the oak might even yield an image we would both be proud of. Until I would eventually return to this patch, whether in two days or in a couple of months, I would remain grateful for our time together and the simple lessons I relearned throughout our visit. They say creativity is not a linear process, and I’ve realized that neither is a person’s openness to the things they consider beautiful.

I wouldn’t know for a couple of weeks how much I actually liked the photograph. At first, it felt almost too spare—too quiet in its simplicity—or a bit obvious at times. But over time, something began to shift. I kept returning to it, almost unconsciously, as if drawn by a calm presence. The composition, which at first seemed elementary and straight on, began to reveal a quiet elegance I hadn’t appreciated at first glance. The open-handed gesture of the branches, the balance of the scene, the way the light slipped gently across the frame—none of it demanded attention, yet all of it held its own kind of grace. It was like getting to know someone who doesn't speak loudly but whose words live on in memory. Within all four corners, I found something lasting—not in complexity, but in clarity.

“Memory of the Present”, Winter 2024 - A few acquaintances I finally got to know better at the end of last year.

Most trees demand more than one meeting to make their best photograph, and, just as with people, sometimes the truest friends are not the ones who dazzle you at first but the ones who invite you to keep looking and listening.

These things don’t reveal themselves in a single snapshot moment. They ask for patience, and they reward it with depth. Like any meaningful relationship, the more time I gave it, the more beauty I found waiting to be seen. This friendly oak, which had long been a hidden, unseen presence, will be a trusty companion on all my future walks through the briars.

- “Briar Patch Companion”, Early Spring 2025

- “Reawakening”, Late Spring 2025 – A newer friendship realized just a few weeks later, after three years exploring its mountainside home.

- “Memory of the Present”, Winter 2024 – A few acquaintances I finally got to know better at the end of last year.

Issue 333

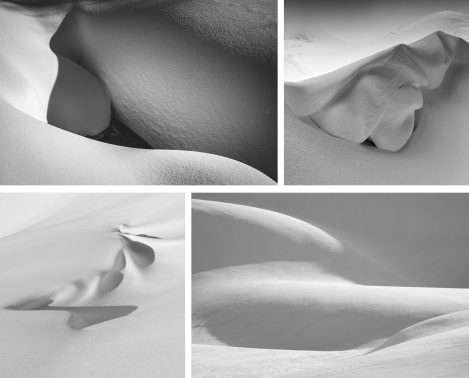

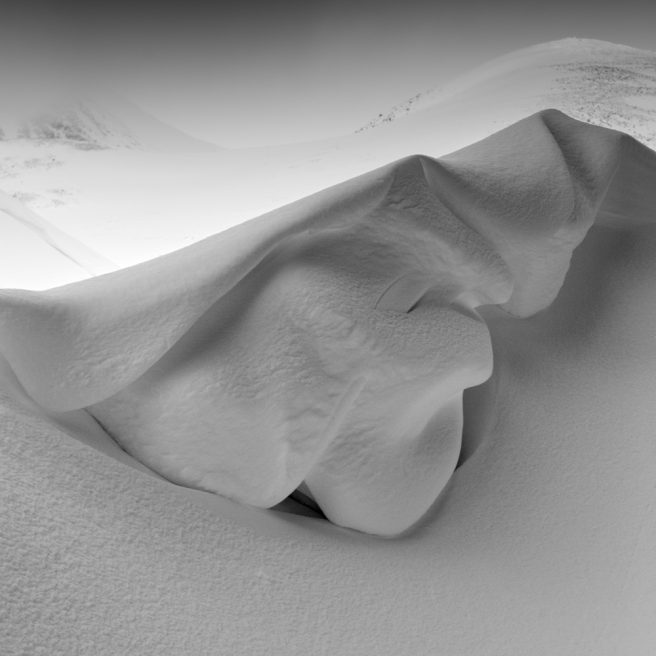

End frame: A Winter Coral by Trym Ivar Bergsmo

‘A winter coral’ is not exactly a landscape photograph. Yet, somehow, it evokes so much of what, to me, makes great landscape photography. Trym Ivar Bergsmo was, in his own words, of the North. He travelled all over the world making images, searching for his ‘inner landscape’, but ultimately found it at home. That home can be different things to different people; the connection is the key. Just like relationships, building those connections takes time, thought, effort, persistence, perseverance, and patience. Looking through Trym’s portfolio, that connection shines through, and it is fitting that the team at ‘On Landscape’ will be writing a tribute to him and his work.

So much of landscape photography is about light; the quality, direction and fall/differential. These aspects may seem outside our control a lot of the time, but the more of a connection we have with our subject, the more we are able to mould these elements to build a narrative. In a winter coral, we have ethereal soft light throughout the frame, but the warmth of the sunlight seems to pick out just a few of the faces and the landscape beyond. This effect is enhanced by the warm skin tones and the red accents in the clothing, yet these elements are not harsh due to the considered use of shutter speed and soft focus. The relatively slow shutter speed also causes the movement in the reindeer, rendering them almost like the flow of a river. There is an organic dynamism to the sense of movement through the frame; it feels alive.

Almost nothing in the frame is pin sharp, yet it conveys so much. They say a picture can speak a thousand words, but a great picture leaves even the words behind. They convey feelings, glimpses, fleeting ideas and emotions; things we often can’t describe or put into words, but we can sense on some, almost metaphysical, level. When you come across images that do that, they make a lasting impression.

These days, our cameras surpass anything we could truly require in terms of technical excellence and the ability to capture almost any scene or subject. Our ability, as photographers, to truly convey emotion remains an elusive skill, though. Generative AI already has the capability to produce almost anything we ask of it, but I dare say it would fail to produce an image with the depth of soul that this one has.

Images like these are not about technical skill or processing power; they are about a human connection and response to a place, people, conditions and circumstances. These things require an open heart and open mind to allow the energy to flow through us, and Trym did his bit to show us the way.

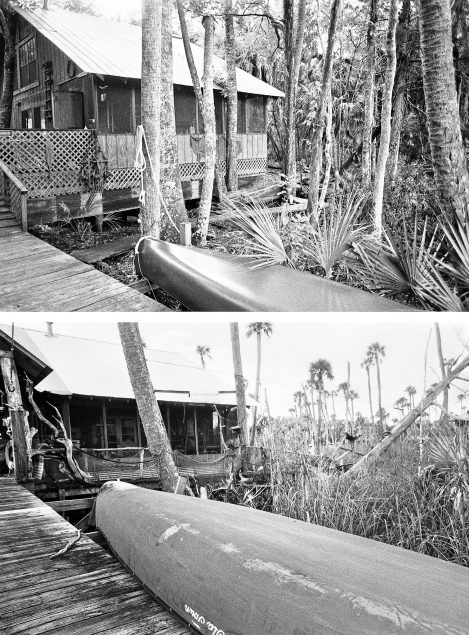

Alex Jones – Portrait of a Photographer

Alex Jones photographs like a designer sifting through an antique store: patiently, curiously, and with a deep reverence for form. His work is not loud; it does not insist. Instead, it invites us to look closer, to notice the quiet details that most would overlook. Each image feels like a found object, carefully selected for its texture, its geometry, or its subtle interplay of light and shadow. This impulse - to collect, to notice, and to preserve is no accident. It traces back to Alex’s childhood, shaped by the dual influences of the natural world and the world of design.

Raised in Tampa, Florida, Alex grew up with architect parents and a mother who was both a connoisseur of good design and a relentless seeker of overlooked treasures. His mother's passion for architecture, furniture, and art museums found a natural extension in her love for thrift stores; she would spend hours searching for the right curve of a chair leg or the perfect vintage lamp.

This aesthetic foundation, rooted in shape, structure, and patient discovery, would later resurface in his photography; but not right away. As a teenager, Alex took a black and white film class that gave him his first real exposure to photography. It planted a seed, but one that lay dormant for years. Instead, he followed a different passion: snowboarding. A high school trip to Utah had introduced him to real mountains for the first time, and the thrill of carving through snow quickly became a lifelong pursuit. That passion pulled him west, where he spent two years as a self-described “ski bum” in Park City. Surrounded by mountains and immersed in the rhythm of outdoor life, his appreciation for nature deepened.

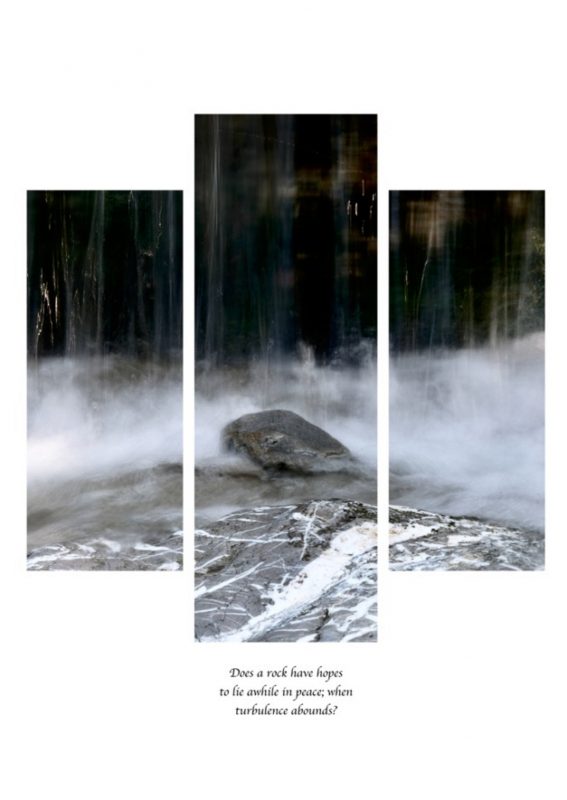

4×4 Landscape Portfolios

Welcome to our 4x4 feature, which is a set of four mini landscape photography portfolios which has been submitted for publishing. Each portfolio consists of four images related in some way. Whether that's location, a project, a theme or a story. See our previous submissions here.

Submit Your 4x4 Portfolio

Interested in submitting your work? We are always keen to get submissions, so please do get in touch!

Do you have a project or article idea that you'd like to get published? Then drop us a line. We are always looking for articles.

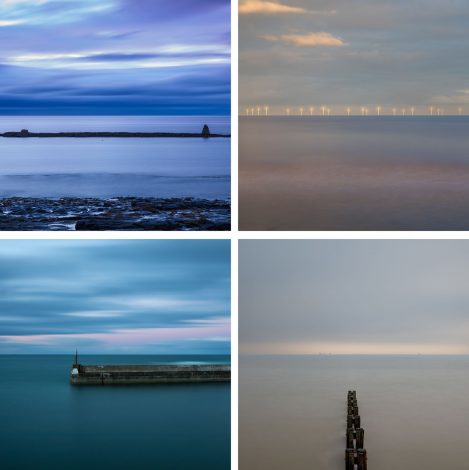

Graeme Darling

The River Bed

Leo Catana

Northern Scandinavia

Robert Hewitt

Humour in the landscape

Ronald Lake

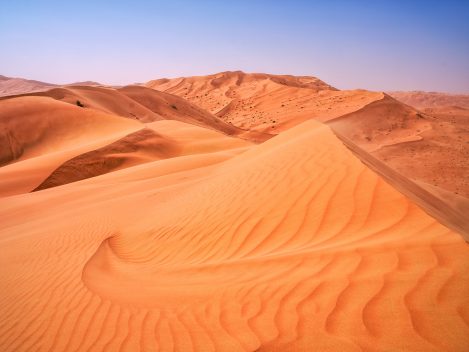

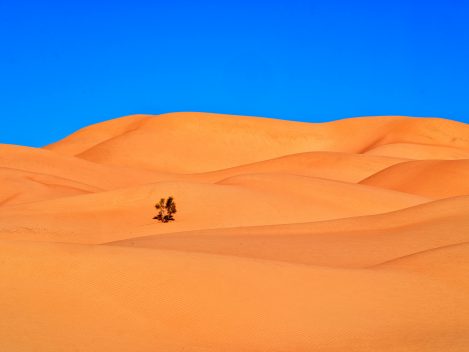

Poplars in Morocco's Ounila Valley

Poplars in Morocco’s Ounila Valley

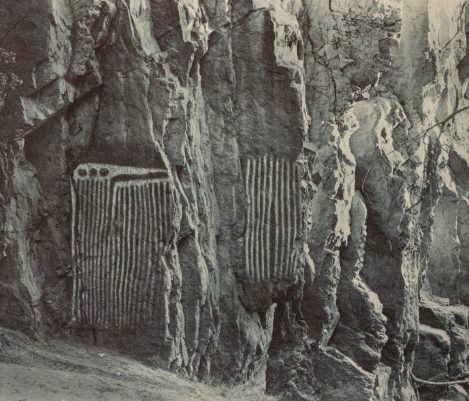

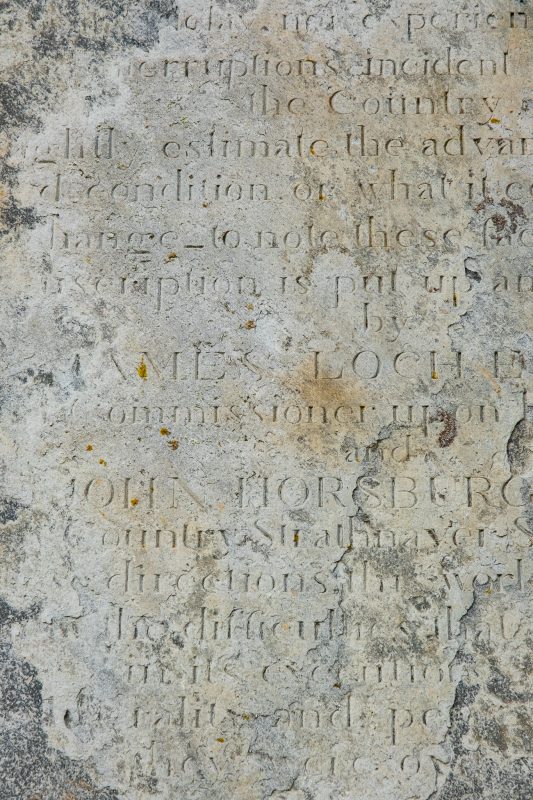

The Asif Ounila River in Morocco runs southward from the Atlas Mountains through a very narrow valley that once was a route for caravans traveling between the Sahara and Marrakech. The most prominent tourist destination along the river is Ait Benhaddou, a walled town of earthen buildings that is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and a film location that has been used in nearly two dozen movies and TV shows, from Lawrence of Arabia in 1962 to Game of Thrones and Outer Banks more recently.

Drive an hour north of Ait Benhaddou and you will see few if any tourists. Instead, there are small Berber (Amazigh) villages dotted along the river. The valley is a thin band of remarkably thick vegetation, a stark contrast to the steep, arid, ochre-colored mountain slopes that loom all along its length.

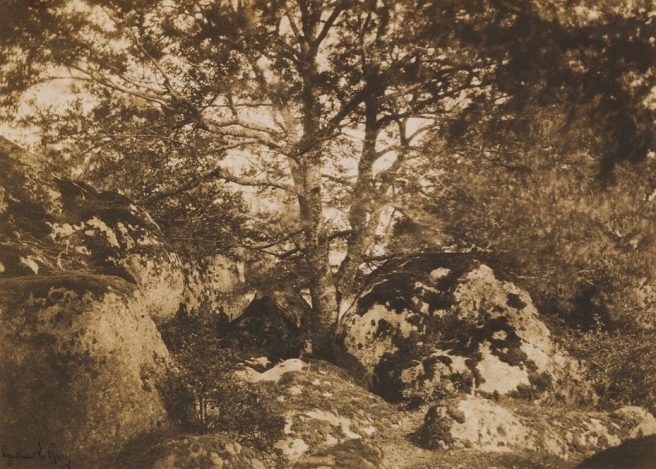

Stands of poplar trees fill the valley. It is still winter, so their leaves are gone. Instead, the filigreed patterns of their branches bask in the early morning light. My mind is no longer occupied by the history of the caravans, the movies, the tourists. Even the mountains recede from view. I simply gaze at the trees, and the colors that surround them.

For me, photography is a form of insight, which aims to reveal essential facets of the world around us and our experience within it. I prefer to make images that challenge our expectations, present a new perspective, and inspire a sense of fascination.

Largely self-taught, I took up photography as a result of visiting Madagascar in 2007. Because Madagascar was so different than the suburban Connecticut environment I lived in, I thought I had better bring a camera with me, and hastily learned the basics of how to use it. Madagascar made such a deep impression on me that I felt compelled to publish a book of my photos (Glimpses of Madagascar: Lemurs and Landscapes, People and Places). Soon after, the book became a featured selection in the Annual Holiday Book Guide of Outdoor Photography magazine, and my photos were exhibited at various places. The recognition was nice, but the real effect of my “beginner’s luck” was to stoke my appetite for doing more photography - regardless of whether I had an audience or not.

Since then, I have lugged my gear around the world, shooting images of landscapes, wildlife, city scenes, and people in such diverse places as Iceland, Scotland, Botswana, Namibia, China, the UK, Ecuador, Antarctica, US national parks, and my own backyard. More importantly, even when I don’t have my camera with me, I find myself viewing and appreciating my surroundings with a photographic eye.

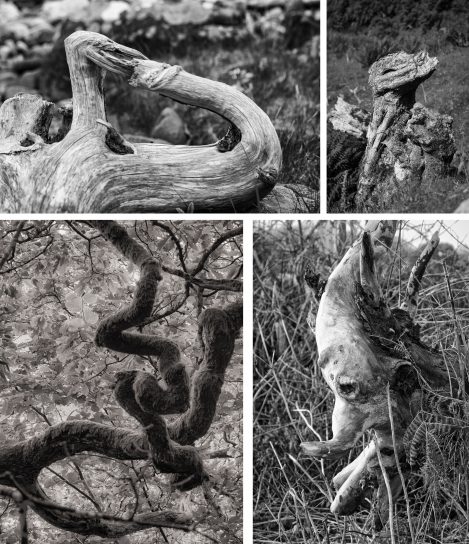

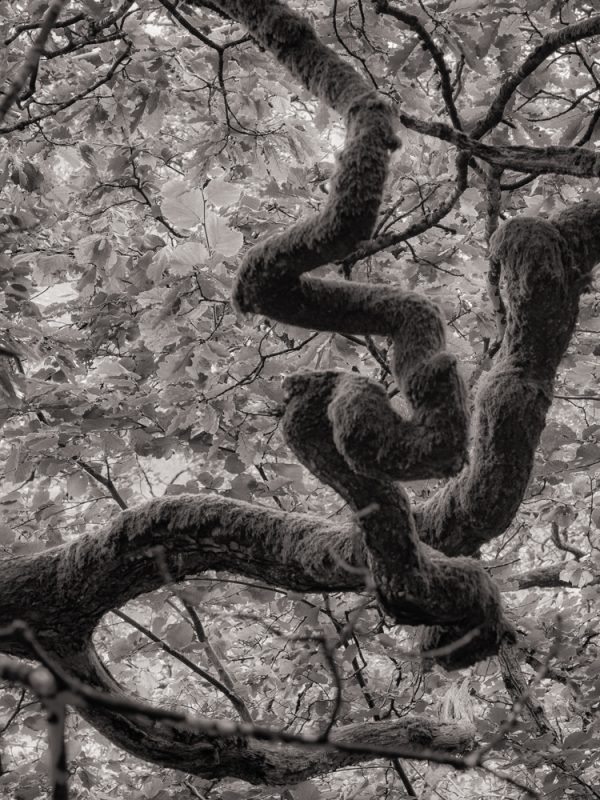

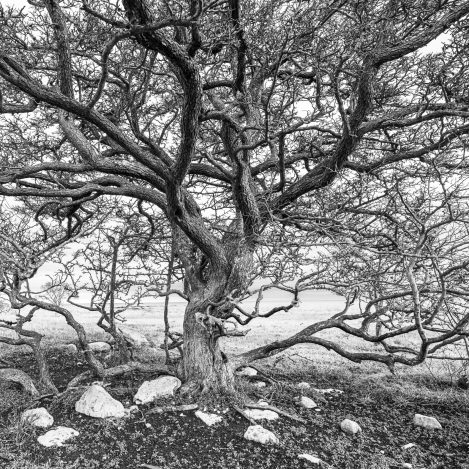

Humour in the landscape

Have you ever played a game of visualising living things in clouds, mountains or landscape? Somewhere, I started a small project, which is ongoing, of recording the humorous scenes in woodland which I came across in my walks or photoshoots.

These 4 images were taken at different times and in different locations. The earliest was taken on the slopes of Cader Idris, where I saw the Welsh Dragon, which started me off. The genie with the bendy knees is a Lakeland offering, whilst the Rhino head is a local scene.

The last image is from Eigg, which seems to show a Swan-like creature eating a snake or its tail! All images let the imagination roam.

This exercise provides an antidote to interesting landscapes where differing rules of composition would apply. All are rendered in monochrome to avoid distractions from the surroundings.

Mostly, the images found would be dead wood, but not always. For example, the sinuous curves of a trunk can be very suggestive.

Northern Scandinavia

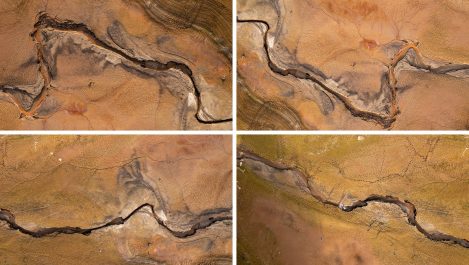

The River Bed

I made the decision around six years ago to purchase a drone when I could not decide which lens to buy for the camera as I realised I was going to a different locations taking a similar composition of a similar subject and it was time to experiment.

The drone gives me a unique view and perspective and a sense of freedom.

Kjetil Karlsen

I was introduced to Kjetil's work when Arild Heitmann submitted his article for his chosen end frame image. Like Arild, I was captivated by the image. As Arild says, "It depicts a typical stormy winter day in the north—visibility reduced to almost nothing, the wind and snow practically lashing out at you. I imagine that’s the sentiment behind the title: you couldn’t be further from lilac blossoms than this." I reached out to Kjetil to find more about his work and the story of his connection to the landscape of northern Norway.

We’d love to hear a bit about your background — what first sparked your interest in photography, what you studied, and what kind of work you do now.

With my curiosity, connection to the nature I was surrounded by, and my creativity, it was my grandmother who first sparked my interest in photography. She was also the one who bought me my first cameras. She always had a camera with her, almost wherever she was. We spent a lot of time together, and her knowledge of nature, her ability to convey stories in combination with photography, opened up a whole new world for me that was exciting and that I took to heart and that I felt familiar with from early childhood. At that time, the pictures were created as something concrete, in addition to the memories. Documentation of events and experiences.

Gradually, the technical elements became more important, and the patience of waiting for the right light, the elements of the image, and the awareness of the meaning of the image became clearer. To me, many of my previous photos appear "empty". Many of them are beautiful, and have good subjective memory. Preferably ,species photos from the world of fauna and flora. But still "empty", because apart from the fact that I have memories attached to each picture, there is no more. And it is this "more" that I gradually start to look for.

One beautiful summer evening in my teenage years, I lay on my back in the grass and looked up at the sky. It was midnight, and the sun was shining diagonally across the landscape towards where I lay. In the same way, the cool wind blew in over where I lay and carried with it the scents of the marshes, forests and mountains, and it was all an intense experience that I knew I would always remember. Then I thought... "How can I convey this feeling in one picture". A picture in which those who see it feel much the same. Of course, it was too ambitious a thought, but it was the start of where I am today.

Later, my interest in human emotions, interpersonal relationships, man's connection to nature and nature's mysticism became stronger, and my experiences with different landscapes and how these affected me became something I had to explore. Here in the north, the landscapes have great variation. It is a short distance from the sea to the mountain plateaus and mountain peaks, although there are large differences in altitude. From the forests that envelop you and invite you to security, to the bare mountain that lies there expansive, black and bare, and that puts man's mental strength to the test, to the mountain peaks that stretch huge and majestic towards the sky. Beautiful and dangerous.

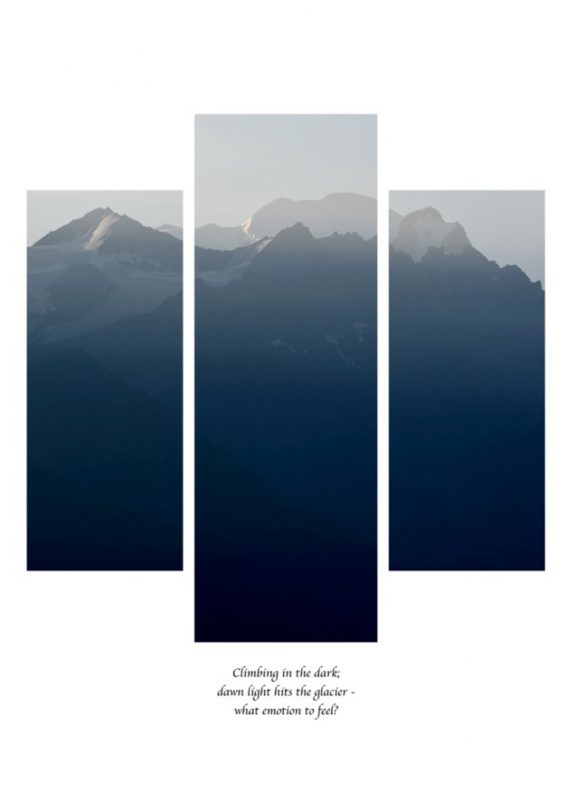

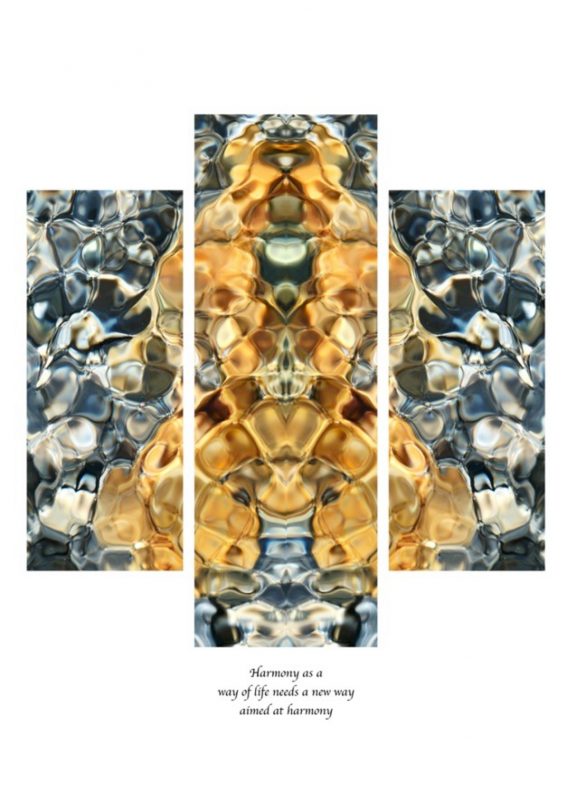

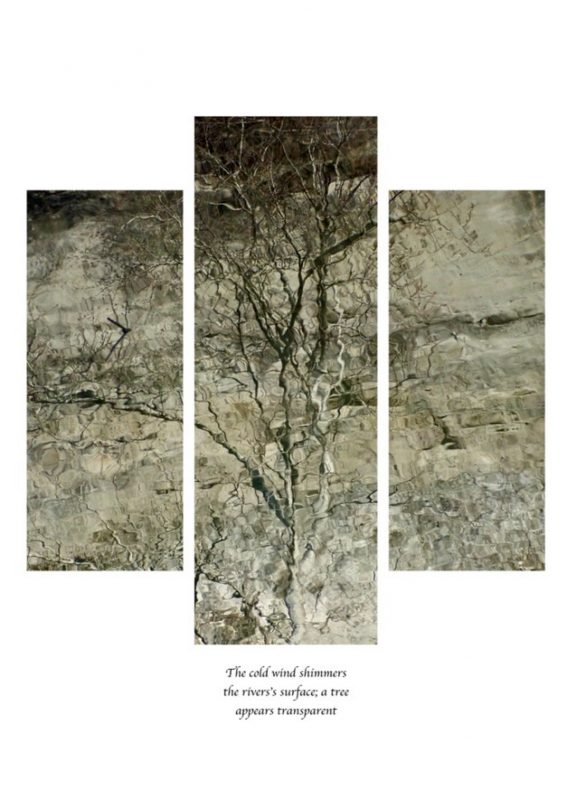

Technology advance and evolutionary adaptation or why it is all about harmony (for me)

The idea that an artistic expression of harmony was an allegory for reinforcing the dominant social foundations is still a compelling argument. Landscape art has long been associated with power and order…. However, at this moment of environmental crisis, creating lyrically evocative narratives that connect us to our landscape is an act of resistance. This way of perceiving the natural world has also become a personal way of building a playful relationship with the landscape that addresses memory, nostalgia, history, landscape, place, storytelling and the passing of time ~Simon Dent, in Shan Shui in Silva Emete1

With film photography we photograph what we saw; with digital photography we see what we have captured without really having looked, nor really been able or even wanted to composev~André Rouille, Le Photo-Numérique: Une Force Néo-Liberale, 2020, p.47

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot ~Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi, 1970

As I write this, I am rapidly approaching 75 years old and thinking that is probably a good point at which to stop producing articles for On Landscape before some elements of old fogeyism start to creep in (and, be warned, this may already be evident in what follows)2. So, this article will be my 30th and last contribution and consequently provides an opportunity for reflection. When I wrote my very first article (some 8 years ago now) on The Science and Art of Hydrology3, it was an initial attempt to try to convey (and help to understand myself) what lay behind the types of landscape images that I was producing, particularly, as an academic hydrologist, those of water. This “trying to understand” has been a recurrent theme in articles since, including exploring some of the debates on photographic philosophies.

Because it has been suggested elsewhere that the technological advances in the last 200 years have far outstripped the capacity for human evolutionary adaptation and that this has resulted in a modernist separation of people from nature, both in the developed world and increasingly elsewhere. At its most basic, the technological developments that have provided shelter and comfort (for most), access to travel (for many), and fast communications and information/disinformation (for nearly all, in the West at least) have also served to create barriers between people and the landscape5. Those developments have meant that we are now living unsustainably on this earth and, in the majority, do not care enough about the exploitation of resources and resulting changing climate (present readers excepted, of course). Or rather that some of us might care, but are not willing enough to make sufficient major changes to our lifestyle to make it more sustainable – and that can often include our photographic practice.

This is, of course, despite the evidence that being out in “nature” is good for us both physically and mentally6. That benefit will depend on the nature and landscapes that are accessible to us, but even urban green spaces have been shown to have important positive impacts (while the negative impacts of exclusion from nature, such as during the Covid lockdowns, are also well recorded). In Switzerland, where I spend much of my time now, nature is readily accessible through good public transport systems and a network of well-marked trails for walking. But even in the Swiss landscape, the negative impacts of technological advances are all too evident when walking past the infrastructure associated with the ski industry, the surface damage resulting from ski runs and access roads, ways of storing water for use in snow canons, valleys drowned by dams for hydroelectric power generation (providing renewable energy of course) and fields disappearing under construction sites. Observing the increasingly rapid retreat of glaciers, accelerated by climate warming, is particularly sad7. That does provide opportunities for some images of waterfalls sustained by glacial melt throughout the summer, but many smaller glaciers will soon be lost completely so even that will not last in the longer term.

On the other hand, technological advances have meant that we have more scientific understanding of nature and landscape. Meteorological, hydrological, geological, pedological and ecological knowledge has been driven by, and also required by, advances in technology in an analogous way that we, as photographers, have driven and served (by buying new gear) the developments in camera technology, as Vilém Flusser pointed out more than 40 years ago. That scientific knowledge means that we could have a more harmonious and sustainable existence on this earth if there were not so many barriers to evolving to doing so.

Traditional pre-technological societies did not have such barriers. They were much more intimately embedded in the landscape, even if more vulnerable to natural disasters. Such societies had to know their landscapes intimately to survive.

But how does this relate to what we do as photographers?

It is evident that there has been dramatic progress in digital sensors over a short period of time, a good breeding ground for GAS and upgrading of kit, even if we do not really need the latest resolution and generation. The result, especially as a result of advances in mobile phones, has been a plethora of images, with resolutions that are way beyond what is necessary for anything that most of us will display electronically or print in hard copy form. It is currently estimated that some 61400 images are taken every second and that nearly two trillion will have been generated in 20249. Storing these images, both locally or in the cloud, requires resources of both hardware and energy that is adding to climate change. Sharing those images across the internet, requires more hardware and energy, that is adding more to climate change. The numbers continue to grow, despite our awareness of climate change and its potential impacts (and there are, of course, many other ways in which we as photographers contribute to CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions10).

It can also be argued that part of the problem is that the camera itself puts another hardware barrier between us and the landscape. Looking through the viewfinder, we do not see a living landscape, we see a potential composition. We “take” images from the landscape in a way that is conceptually a form of exploiting the natural resource. Normally, that might have only a minimal impact (depending on how far we have had to travel to be there) but there are also some particularly vulnerable sites made popular though Instagram and YouTube where selfish or careless photographers - or just the sheer numbers of photographers - are damaging the site to get the shot or even just to take a selfie with the landscape as background11. Our adaptation to the technology is greater than our adaptation to the threats to the landscape and to life within it. In part that is because we are rewarded by our use of the technology - in having a record of our lives, or images that we can share with others, exhibit or put in a book.

With digital this has become even easier, because we can immediately review the images we take. We are encouraged by the technology to make ever more use of the technology. The numbers of images continue to grow and grow, encouraged by the apparent low cost of digital images, but with the all-but-hidden cost of using more and more resources (and the impact of AI generated images is only just starting to be felt)12. So now, on the one side we are overwhelmed by images of landscape beauty, and on the other we are overwhelmed by images of landscape loss and destruction (and the impacts of war and famine). We allow both to coexist, discordantly, in our minds and, sometimes, our practice spans both.

It is recognised that human evolution and adaptation is shaped by culture and technology much more rapidly than can occur by genetic changes.

Culture provides a second, and extraordinarily powerful, way of evolving. Genes encode information about phenotypic solutions to problems that organisms encountered in the past, and that information is transmitted only from parents to offspring. By contrast, cultural information—knowledge, technology, ideas and preferences—can be disseminated broadly, and the information can accumulate within a single generation ~Richard Lenski, 201613

Indeed, it has been argued that humans have put limits on the process of natural selection by having the technology to ensure that nearly all children survive to adulthood.

There's been no biological change in humans in 40,000 or 50,000 years. Every thing we call culture and civilization we've built with the same body and brain ~Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), 200014

So what needs to evolve culturally to deal with this technological overload and failure of sustainability?

Is it possible to bring some harmony to this cacophonous cascade of discords? Harmony has long been taught as one of the fundamental principles of art (the others commonly cited being balance, emphasis, movement, proportion, rhythm, unity and variety). Harmony in this sense means having a good balance of elements of colour, value, shape and textures in an image to produce an effect of wholeness. There are many articles online about harmony in photography, for example on how to use the colour wheel and complementary colours in composing an image (or, less happily, in how to modify colours in post-processing for greater harmony and impact)15. But harmony (as well as its musical connotations) also has the wider definition of living peacefully with one another, or of living in harmony with nature.

It is naïve, of course, to suggest that pre-technological societies lived in harmony with nature. They also exploited nature for survival (and in some parts of the world still do) and were affected by natural disasters of floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

In fact, we are not short of philosophical advice about achieving harmony, from Confucianism and Taoism in ancient China; the Vedic philosophy of ancient India; Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics in ancient Greece; Marcus Aurelius in ancient Rome; to Leibniz, Schiller, Santayana and Naess in more modern times17. There was even a 2010 report by the Director of the United Nations that linked the goals of sustainable development to living in harmony with nature18.

Dwell on thoughts that are in harmony with nature and her laws, and act accordingly. Don’t let yourself be pulled off course by the insults or injuries of others. Let them go their way and you go yours, continuing on the path of reason. This is not selfish or antisocial on your part—far from it. Your individual reason is not opposed to the common good, but in harmony with it.” ~Marcus Aurelius, 121-180 BCE

While human evolution has changed little with the advent of industrial technology, clearly societal evolution and the nature of thought have changed dramatically in the last two centuries since the Enlightenment and its myth of understanding and controlling nature that drove the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. While we still create myths of sustainability today, underpinned by idealism as well as science19, modern society is largely based on exploitation of both nature and people. The ideals and myths of living in harmony with nature have been largely lost. If we think about images in this way, then those that reveal the beauty of landscape might be considered as attempts at harmony; while those that represent loss and destruction are recording the ways we are failing to live in harmony with nature. Making and presenting either type of image can be considered as a political act (even if we rarely think about it in such terms), but the cases where the such images have had real political impact appear to be few.

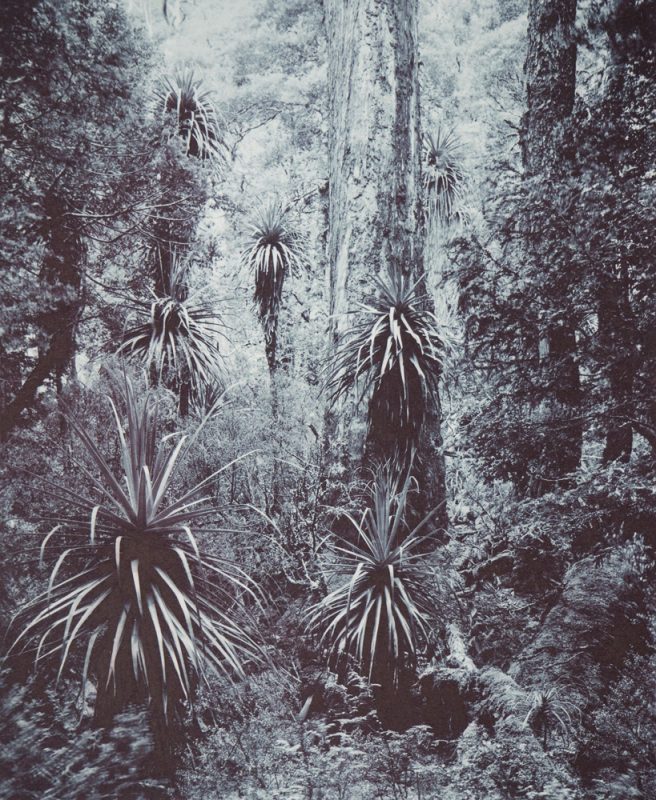

Those few celebrated cases do, however, include the role of the images of Carleton Watkins in the designation of the Yosemite Valley as the first National Park in the US in 1864; the images of Ansel Adams (1902-1984) in the formation of the Kings Canyon National Park by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940; the images of Horace Kephert (1862-1931) and George Masa (1885-1933) that influenced the designation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 193419; the Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend image of Peter Dombrovskis (1945-1996) in saving the Franklin River in Tasmania from hydroelectric power development in the 1980s21; and the Colorado photographer John Fielder (1950-2023) whose work inspired the Colorado Wilderness act that created 36 wilderness areas in the state22. But the images of Eliot Porter in The Place No One Knew23were too late to save the wonders of Glen Canyon from inundation under Lake Powell (though recent long term droughts, thought to be exacerbated by climate change, have allowed some of the side canyons to be visited again).

While Walter Niedermayr’s striking images of the Alps, including skiers and ski infrastructure, are also political in this sense of raising awareness, they have not resulted in any constraints on development. Martin Parr’s Small World images have not had led to any mitigation of the overtourism that is producing demonstrations and active resistance in places such as Barcelona, Venice, Mallorca, Bali, Santorini, and even rural Galicia24. Some of the aerial images of the destruction caused by mining and tailings by Edward Burtynsky even give the impression of abstract beauty, and certainly have not had any impact on the sustainability of mining practices25.

All the images of retreating glaciers, both by photographer artists, scientists and satellites have had little impact on national policies, even in Switzerland and other countries being significantly affected (some 10% of glacier volume in Switzerland has been lost in the last 2 years26). All the artistic images of lakes and rivers in Britain have failed to stop the illegal releases of untreated sewage that is having such an impact on the water quality and ecology. Even images of the sewage releases or resulting eutrophic algal blooms and all the scientific data that has been collected, including by citizen scientists, and public demonstrations have not yet had any significant impact on the practices of the water industry or policy in government27 (but we should hope that will not last). All the wonderful images of the amazingly skilled and dedicated wildlife photographers have done little to halt the decline in numbers of birds and animals as we live out the 6th mass extinction28.

Indeed, it can seem that images reflecting the beauty of nature only serve to suggest that the degradation is not so serious. Perhaps the very fact that image numbers continue to grow and grow only serves to minimise such political impacts. The sheer numbers have only meant that images will be less effective than 80 or 100 years ago. Already as individual landscape photographers, we tend to have an overload problem with the images we take ourselves, since although we will not consider them all to be of the highest quality it is still difficult to delete all the others since our opinions might well change in a few months or years (…though again that storage really does have a real cost in resources and energy, even if our travel to get to the places we photograph might dominate any other photography related energy consumption or CO2 emissions). That is not to say, however, that the hope for political impact, has died out. Richard Sharum, talking about his recent book Spina Americana, stated:

It reflects my general philosophy towards photography as an anvil for activism, as well as my opening argument for a new direction in the hope for a more collective and persistent empathy.29

I suspect that most readers of On Landscape will lean towards harmony with nature in ways that reflect our own emotional responses. Many will be prepared to argue that in attempting to show how beautiful nature can be, we strengthen the case that is worth preserving. That has certainly been the foundation for much of my own work. As such, although we do “take” our images from nature, we also want them to be a fairly faithful realisation of the real scene. We would like to hope that the image has some harmony with the viewed reality, our felt experience of being there, and what that reality might mean to us in a time of change.

This was precisely the goal, or mission, of film photographers: to fix a centre to the chaos of the world, to subject it to a geometric order and extract a truth by eliminating, cutting out, purifying until we end up with an intentionally constructed shot, captured at a “decisive moment” … At the opposite end of the spectrum are digital photos: too quickly taken, too fleeting, often too banal; they undermine the viewer's desire for the aesthetic experience of contemplation … The quest for truth has been transformed into a consumption of fictions ~André Rouille, Le Photo-Numérique: Une Force Néo-Liberale, 2020, p98/89/98

Many landscape photographers have written about the value (be that physical, psychological or spiritual) of being out and about in the landscape, over and above any images that we might bring back from any of our excursions. It does not even need any camera to be involved, which brings me back to my favourite photographic quotation, much cited in On Landscape30 and elsewhere, of Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) in the Los Angeles Times of 13th August 1978, that “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” The advantage of going for a walk with a camera is that it really concentrates the mind on looking, in particular in seeing some of the detail of what is there (and perhaps then create a composition)31.

And, returning to Vilém Flusser, there is always the challenge of avoiding redundant images. It is ever more the case that everything has been done before, that every new image is in some sense redundant, another version of the same. It might be our own version of what has been done before, with a degree of personal satisfaction of capturing the shot, but might there not be more interesting ways of trying to avoid redundancy? One way that might be more harmonious could be to explore the locally unique surroundings in preference to those highly photographed places that require long distance travel and that have been seen so often before. There might then be more satisfaction in the hunt to find something more original, more personal, than going somewhere far away to only produce redundant images you will already have seen. As David Ward put it:

It's important to me that I am making an enquiry about my surroundings in my images, rather than imposing a conclusion. I am not seeking to make definitive statements because I don't know the answers. The questions vary enormously from image to image; I might be asking about the colour of light or what is it that is beautiful about moving water or why I find that arrangement of elements interesting or musing on the ecology of a particular place.” ~David Ward in Nobody Expects the Inquisition32

This implies that we need to evolve a deeper, more thoughtful, approach to the landscape. Many landscape photographers are there already, of course, including the readership of On Landscape and those photographers following the 7 Nature First principles33 to minimise impact and to leave no trace of our passing in making our images (and ideally in the manner of our getting there too). As with the Swiss glaciers, seeking harmony has to represent more than recording their current beauty in the process of disappearing34. It should involve a consideration of what might be required to preserve that beauty in the long term, to ensure that that our relationship with the landscape might be sustainable in this technologically dominated world. But is then the viewfinder a barrier to thinking in that way and acting according? I think it can be. I think it has been in my photographic life in the past which has not always been so thoughtful about the impacts we have, even though as far back as I can remember I have cared about the landscape35. We have to think, therefore, outside the box, whether it is in hand or sitting on the tripod! To achieve some degree of harmony, both as one of the fundamental principles of art, and in the sense of our reflecting our own authentic feelings about a place or element of the landscape.

So in this, my last, article for On Landscape can I encourage all who might read this piece to evolve your thinking and practice towards a more ancient idea of harmony with nature, and consequently to be more thoughtful about your approach to the landscape and the sustainability of its beauty. That does require a philosophical stance, perhaps the personal philosophy of harmony as advocated by Arne Næss. What might that look like? It means thinking about harmony in the sense of sustainability in the long term, with the classic dilemma that sustainability implies policies at national and global scale and what we can do as individuals seems so miniscule. But if we do care, we should do what we can to live more sustainably; to think about our impacts on the landscape; to reflect nature (and not some artificial or augmented reality); and to reveal the wondrous details of nature that might otherwise be missed so as to encourage the recognition of their value.

You will, of course, appreciate that it really does not seem to be the way the world is going. There are more and more images that are simulacra or constructed reality rather than simulationsin the sense of Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007)36. But in terms of social evolution, education is important. Teach your children well, as the Graham Nash song says37. Do we need to do more to educate our children about nature and landscape before it becomes something that most will only experience as virtual realities in games, as nature documentaries on screens (however wonderful), or as distant backgrounds in selfies38? It is not as if we have not been aware of such change for a long time. If Vilém Flusser has not been widely read, even by photographers, in more popular culture Joni Mitchell was singing, as long ago as 1970:

“They took all the trees and put 'em in a tree museum

And they charged the people a dollar and a half to see them

…

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you got 'til it's gone?” 39

Current technologies create barriers to real experience in favour of experience filtered by the technology. The response to the technology in this case is currently evolving to put the self before the landscape. The rise of the selfie represents a form of disengagement with nature, encouraged by the technology in a way that is not sustainable, but it is also not a necessary consequence. We can evolve our practice to stay aware of what is needed for sustainability and of harmony with the landscape. To cite Brad Carr:

The camera is a vehicle that can carry us towards a place of deep healing, resulting in self-acceptance, and, therefore, acceptance of others. Nature, I believe, is the portal through which we now need to travel if we wish to reverse the damage of the past and co-create a more peaceful, harmonious and loving world to exist in tomorrow.40”

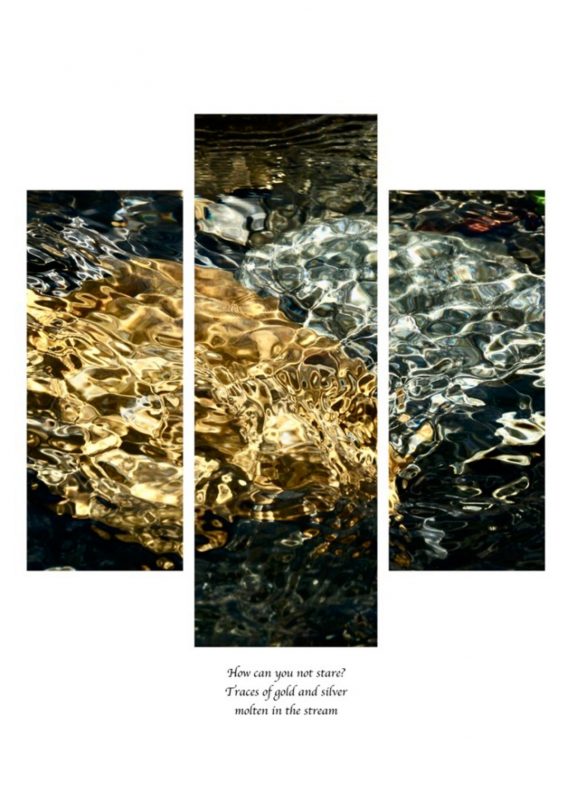

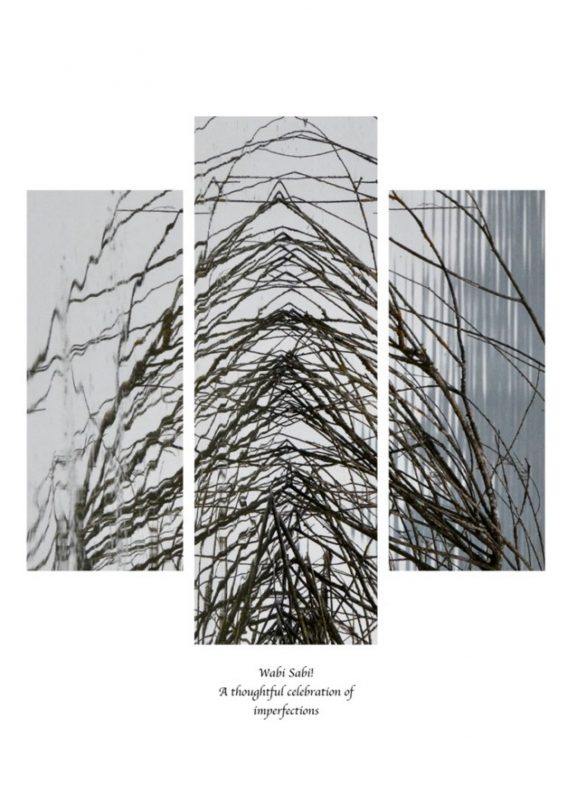

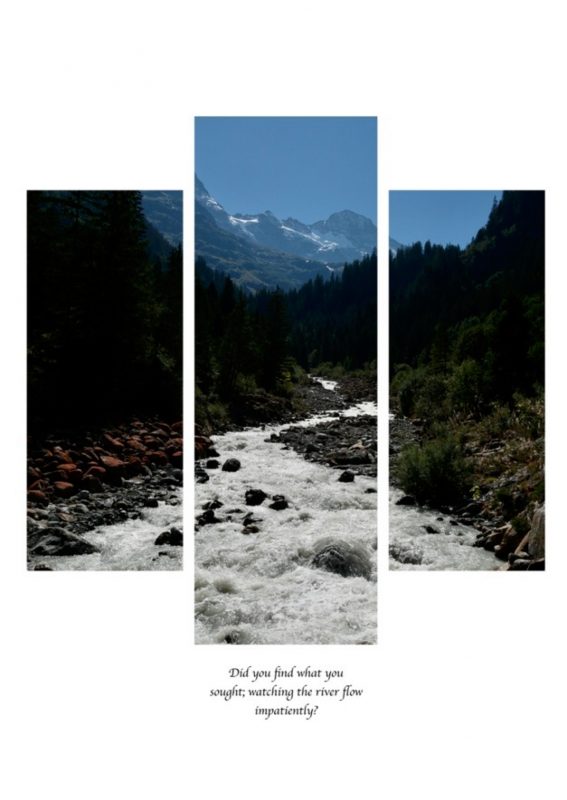

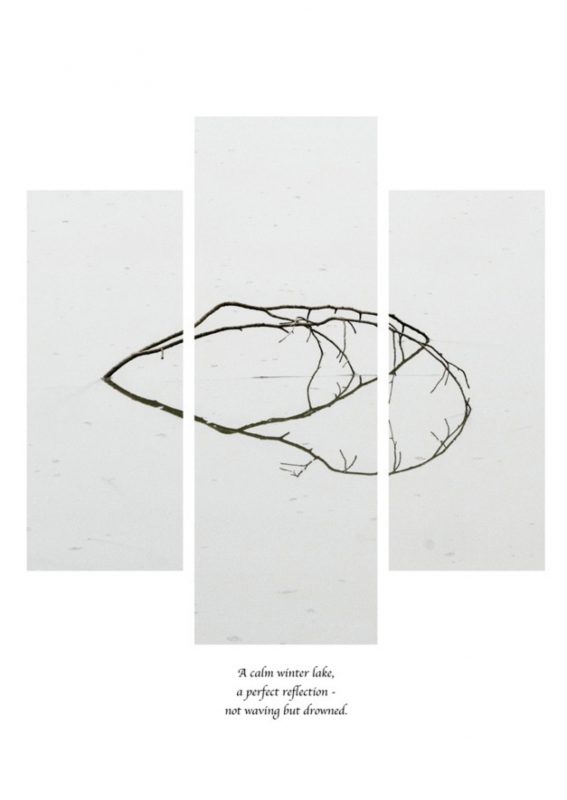

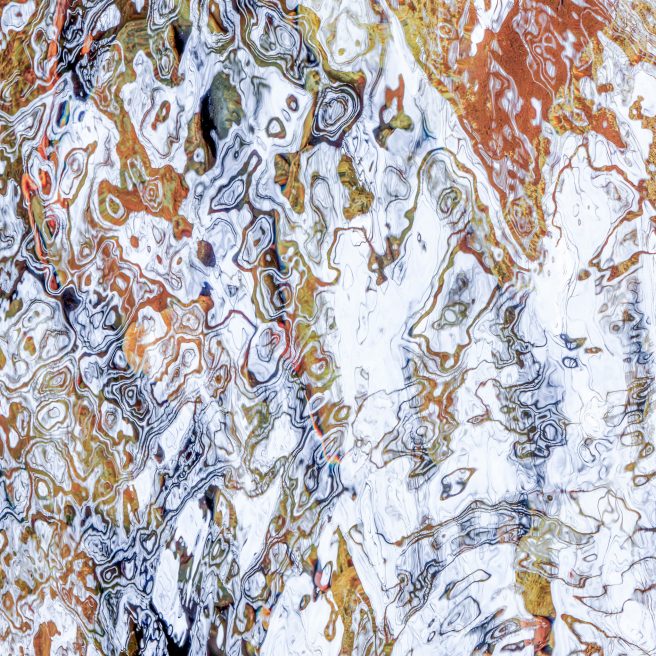

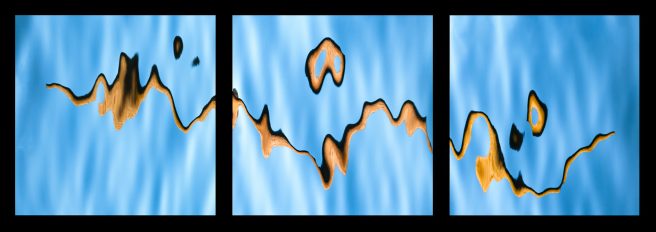

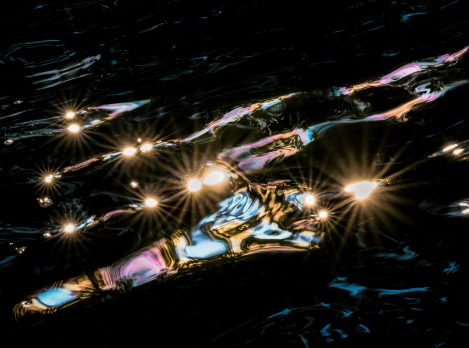

That then is my two-penn’orth. I will stop now and leave you just with a few final images of some new visual haiku, taken from a second volume The River as Haiku41. These have been taken with harmony in mind, mostly on walking trips from our front door or reached by public transport. I hope you will be able to find projects of your own that allow you to do the same.

References

- https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2023/10/shan-shui-in-silva-elmete

- An old fogey may derive from the Scots foggie, fogie (noun) from foggie (“covered with moss or lichen; mossy”, adj) to suggest a dull person (especially an older man) who is behind the times, holding antiquated, over-conservative views. The OED's earliest evidence for old fogey is from 1785, in a dictionary by Francis Grose, antiquary.

- In Issue 135, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/04/the-science-and-art-of-hydrology/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2020/06/landscape-and-the-philosophers-of-photography/

- The writings of the iconoclast philosopher Ivan Illich (1926-2002), active in the 1960s and 70s, are worth exploring in this respect. It was he who, in his book Tools for Conviviality, suggested that the ideal form of transport was the bicycle as a compromise between going further and spending more time travelling. Anything faster and it would necessarily result in more time spent travelling. The proof of this is all the wasted hours spent in airports by many people since. His books on Deschooling Society and Medical Nemesis are also worth reading.

- See, for example, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/sep/04/better-than-medication-prescribing-nature-works-project-shows

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/05/loss-in-the-landscape/ in Issue 231

- See, for example, Cost–benefit analysis of flood-zoning policies: A review of current practice at

https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wat2.1387 (open access). In Switzerland, the risks are also getting greater as seen recently in the failure of the Birch glacier and consequent rock avalanche that buried most of the village of Blatten. This type of risk is increasing as a result of the loss of permafrost in the mountain soils. - See https://photutorial.com/photos-statistics/. Note that Vilém Flusser already talked about the redundancy of most images well before the age of digital photography. A more recent discussion along similar lines is the book by André Rouille, La Photo Numerique – Une Force Néo-Libérale, L’Echappé: Paris, 2020 (in French). The arguments on the service of the digital image to capitalism are not always convincing but the discussion is interesting. André Rouille has published a number of books on photography and maintains the site www.paris-art.com. The only book of his I could find that has been translated into English was A History of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives with Jean-Claude Lemagny from 1987.

- See the article by Joe Cornish in Issue no. 180 https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/03/a-question-of-responsibility/ and the discussions that followed.

- See the article by Matt Payne on concealing locations, especially sensitive locations, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2024/12/geotagging-gatekeeping-location-sharing/.

- An academic paper on Life Cycle Analysis of film and digital imaging from 2006 suggested that:

When all impacts were considered, no single imaging scenario was clearly "better" or "worse" than the others. Imaging scenarios that were advantaged in one impact category were often disadvantaged in others. This leads one to believe that a more complete picture (with more impact categories) would also not show an “absolute winner.” See https://www.mech.kuleuven.be/lce2006/070.pdf. However, their figures suggested that the lifetime number of images for a film camera at that time was only 4800, and actually more than a digital camera at 4500. The number of digital images produced per year since 2006 has expanded exponentially. - http://assets.press.princeton.edu/chapters/s10711.pdf in Jonathan B. Losos and Richard E. Lenski (Eds), 2016, How Evolution Shapes our Lives, Princeton University Press, Chapter 1

- Gould, S.J. 2000, The spice of life. Leader to Leader. 15:14–19., see also Templeton, AR., 2010, Has human evolution stopped? Rambam Maimonides Med J. 1(1):e0006.

- E.g. https://iso.500px.com/color-theory-photographers-introduction-color-wheel/

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arne_Næss. Næss actually called his own ecological philosophy Ecosophy T where the T referred to Tvergastein, the mountain hut where he wrote most of his books. He encouraged people to develop their own personal philosophy.

“By an ecosophy I mean a philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium. A philosophy as a kind of sofia (or) wisdom, is openly normative, it contains both norms, rules, postulates, value priority announcements and hypotheses concerning the state of affairs in our universe. Wisdom is policy wisdom, prescription, not only scientific description and prediction. The details of an ecosophy will show many variations due to significant differences concerning not only the 'facts' of pollution, resources, population, etc. but also value priorities.”

Arne Næss, in Drengson, A. and Y. Inoue, eds. (1995) The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Publishers.p.8 - Even our current King has been involved in a book titled Harmony: A new way of looking at the world, co-written with Tony Juniper and Ian Skelly in 2010 - https://kings-foundation.org/about-us/philosophy-of-harmony/

- https://www.garn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Harmony-with-Nature-United-Nations-Report.pdf. This followed General Assembly resolution 64/196 with the title Harmony with Nature

- See for example the 2024 book Agrophilosophie: réconcilier nature et liberté of the French author and philosopher Gaspard Koenig, who proposes a system based on principles of recycling and individual responsibility for a sustainable soil, scaled up to local self-governing communities and to federal nation states with limited powers. He is not so convincing on how to persuade societies to move towards such a sustainable option unless some “miraculous political circumstances” appear somehow. See https://editions-observatoire.com/livre/Agrophilosophie/544

- See, for example, https://smokieslife.org/product/george-masa/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/06/morning-mist-rock-island-peter-dombrovskis/

- See https://petapixel.com/2023/08/14/revered-landscape-photographer-john-fielder-dies-after-cancer-battle/

- Eliot Porter, 1963, The Place No One Knew, 25th Anniversary Edition published by Peregrine Books in 1988 (ISBN 978-0-87905-249-2) and reprinted in 2000. Michael Engelhard, in his 2024 book No Walk in the Park, points out that Eliot Porter’s book should really have been called The Place Not Many White Men Knew, since there were many places in Glen Canyon that were sacred to the indigenous peoples. The history of the Glen Canyon Dam controversy is summarised in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glen_Canyon_Dam.

- As reported in https://www.euronews.com/travel/2024/09/02/paradise-ruined-why-spanish-locals-fed-up-with-overtourism-are-blocking-zebra-crossing

- https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs