Another instalment of the lockdown podcast where Tim Parkin, Joe Cornish and David Ward discuss a few questions around photography including "How is the easing of lockdown affecting you?", "How do you make the most of a photography workshop?", "What makes a good photography book?", "How do you see your photography changing over time?" and "Do you have any other non-photography creative outlets during the lockdown?". Here's a clue to the last question - you can guess whether it's from me, David or Joe.

Three Rocks, The Butt of Lewis

I took this shot, which I was delighted was selected as the overall winner of the Scottish Nature Photographer of the Year competition 2019, from the lighthouse at the Butt of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides in October. I was staying in Aird Uig which in itself is spectacular and fascinating due to its connections with the Cold war. Located on the west of the island, Uig (also known as West Uig and in Gaelic, Sgir Uig) has a multitude of breath-taking beaches, bays and coves on the doorstep. However, the weather forecast was for wind and heavy showers so where better to experience and capture these conditions than at a lighthouse?

The lighthouse at the Butt of Lewis marks the most northerly point of Lewis. The drive from Uig to the Butt of Lewis took me past the Callanish Stones. The stone circles here are captivating and awe-inspiring. Dating back to around 3400 BC, they, of course, raise the questions of Why? Why here? How? What for? The sense of past and present being inextricably linked is palpable here. But for the photographer, the stones provide both opportunities and challenges. Trying to capture – and do justice to- the overall scene is very difficult. Instead, focusing on detail and pattern within the groupings often produces some striking results. However, it takes time to really capture the essence of this place, and this was not the day for such an endeavour.

Moving on took me across a flat and in places, quite desolate landscape, but with small roads off to the left leading down to rocky coves such as at Borve (not to be mistaken with Borve on Harris). A wide sandy bay with smooth sand dunes at Eoropie/Eoropaidh beach was also enticing and is certainly worth exploring. But the wind was picking up and with it my determination to reach The Butt, recorded in the Guinness Book of Records as the windiest place in the UK.

The lighthouse was built in the mid 1800s and is unusual in that it is of red brick rather than painted white as is more common in Scotland. At the time of building, there was no road access and so all materials had to be brought in by ship.

However, for me, the starring role is played not by the lighthouse but by the rocks themselves rising up from the tumultuous waters below. These are ancient rocks, Lewisian Gneiss, formed 3000 million years ago and some of the oldest rocks in Europe. The textures and patterns, angles and structures are visible amid the many seabirds that cling to the rocks and swoop in and out of the waves. The cliffs on which the lighthouse stands are between 60 and 80 feet high so are not the highest of cliffs, but looking down from them and across to the surrounding rock formations, is nevertheless a highly vertiginous experience. I cautiously approached the edge to find a suitable spot from which to shoot, wary of the gusting wind which threatened to take me towards, and perhaps over the edge. Fortunately, there were some safe flat spots to set up my tripod and begin to consider composition. The Butt of Lewis is wild and unforgiving. It is here that the raw force of nature is truly evident.

Trying to capture this essence is a challenging task.

A range of other shots were of course taken during the day spent at this iconic spot which accompanies this article.

Driving back, I stopped off at the Comunn Eachdraidh Nis, a museum, gallery and café set up to collect and preserve local history and to create a community hub. This has fascinating photographs and other materials relating to the history of the area and its inhabitants and is well worth visiting. While enjoying my tea and home-made cake, I had no idea whether any of the many shots I had taken would be of any quality given the ferocious conditions. Despite this, I felt the warm satisfaction that comes from spending a day truly getting to know and appreciating a location, which of itself is a wonderful experience.

The Hill

‘The Hill’ will not be found in any guidebooks or lists of ‘must-visit’ places. It will remain unknown, unvisited, even by most of the people who live nearby. It is of modest height – barely topping 1,000 feet – and from afar has no distinguishing features to separate it from other rounded forms in the West Pennine Moors. A housing estate encroaches upon its south-western slopes, a golf course to the south. It is usually a wet, soggy place of wind and rain. And yet, it is a remarkable unremarkable place that plays an important part in my photography, though not necessarily in terms of actual photographs.

‘The Hill’ is Cheetham Close, a hill that lies at the northern edge of Bolton,

A stroll up the hill acts as a seasonal reminder of the constant, subtle changes in nature that can often pass unnoticed. As I write this in early March three lapwings have just returned to the horse field to begin their acrobatic courtships while higher up on the moor the skylarks are tuning up, ready to make a mockery of Vaughan Williams. The plaintive call of the curlew occasionally haunts one’s passing along the summit moor and very rarely I may be lucky enough to hear the bizarre sound of a snipe drumming.

The moor itself can frequently appear bleak, empty, unchanging until you observe the transition of the moorland grasses from the vibrant, urgent growth of spring, through the dull established green of summer followed by a few weeks of intense orange before settling into the pale straw of the long winter. And then there is the glory of cotton grass. For a few weeks in May and June the bobbing white heads of swathes of cotton grass are a sheer delight. Every year I await the display with anxious anticipation, wondering if there will be much of a show or even wondering where the best displays will pop up as the cotton grass appears to travel along the moor.

Wandering through the rough pasture below the hill one can observe the growth of the trees planted 15 years ago – the birch, hazel and hawthorn growing slowly, slowly; the empty green tree guards marking where the struggle was too much. The sudden burst of hawthorn blossom will remind me to explore the fells of south Cumbria and the Dales while the succession of wildflowers – lady’s smock, bilberry, bluebells, tormentil, batchelor’s buttons, and spearwort – hint at the potential displays elsewhere. In July I wait in anticipation of the foxglove stand that grows near the bench – some years extraordinary, others a sad disappointment. Of an evening you can startle a deer, spot a fox skulking through the long grass or, most magical of all, follow the silent quartering of the pasture by the elusive barn owl. The only constant on my walk is that there will be something different, something to observe, some reason to say, ‘Hey, look at that!’

The Hill played an important role in the development of my photography. My first ever magazine competition win was with a photo of an old wooden gate on the shoulder of the hill under snow on a gorgeous winter evening; my first cover photo for Lancashire Life was a view towards Winter Hill from the summit and my first Viewpoints article for Outdoor Photography was of Cheetham Close. Ideas for photo projects or articles (including this one, of course) are often born while enjoying the freedom of thought on the walk.

These days I rarely take my full kit out on the hill but my Sony compact sometimes accompanies me and I enjoy the spontaneous freedom it provides. Ultimately, though, the influence of the hill is the exposure on the walk to the constant changes in nature that help to reignite my curiosity and rekindle my desire to explore, even if that may be elsewhere.

Postscript

And then there was lockdown.

No more jaunts to the Dales or Silverdale. I am restricted to ‘The Hill’. How lucky I am!

I composed the article in early March and now a lot more people are familiar with ‘The Hill’. Initially, I was very proprietorial, objecting to all these ‘Johnny-come-latelys’ spoiling my sense of exclusivity but now I realise that it has become an important part in the daily lives of many people in the area along with the reservoirs and strips of woodland currently bursting into life. So many more people are now enjoying the beauty on their doorstep and I’m sure this is being repeated all over the country – small pockets of nature providing essential contact with the natural world. Remarkable unremarkable places.

This can only be a good thing. People are becoming more connected to the natural world and feeling the benefits of a simple walk in the countryside. Furthermore, the regularity of that contact means that they are observing the variety and daily changes of spring that they would most likely miss in more busy times. One can but hope that there will remain a sense of the importance of nature and a desire to look after it a little better when things get back to normal.

In the meantime, I myself am exploring paths I’ve not walked for over 15 years (or at all in some cases) and reacquainting myself with some of the natural delights of the West Pennine Moors, compact camera in my pocket and enjoying the freedom of taking a few snaps on the way.

Issue 206 PDF

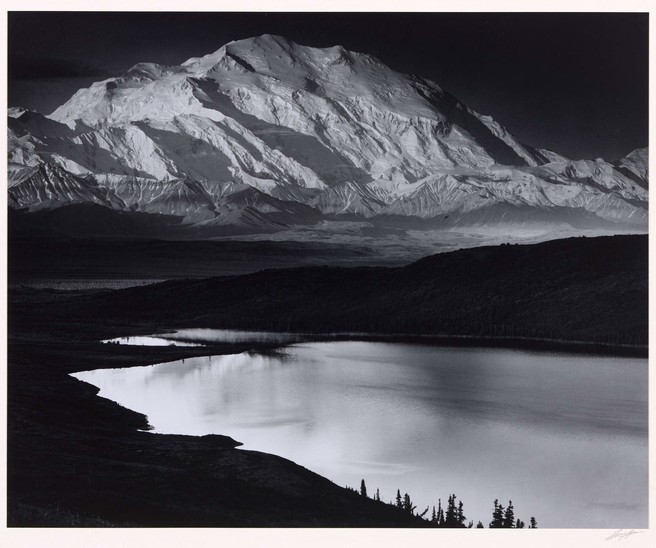

End Frame: ‘High Light’ by Colin Prior

I don’t think that Colin Prior (watch Colin's presentation at the Meeting of Minds Conference 2018) needs an introduction to anybody with a certain degree of interest in landscape photography. And surely not to the profound readership of On Landscape. Hence, I consider the opportunity to express my feelings towards his unrivalled body of work a true honour.

The chosen photograph shows the mountains of Assynt, Scotland, on a wintery evening. In this image, you can see how wonderful evening light accentuates the peaks of Stac Pollaidh, Suilven, Cùl Mòr and Cùl Beag. The illumination seems to be one of these special theatre lights that bath the actors on a stage. It is a photograph in which light is a tangible character thanks to its presence on the mountains. It is a true frame of genius, and exemplary for all his stunning 3:1 panoramic work. Browsing through his Magnum Opus “Scotland’s Finest Landscapes”, any photo would deserve to be exhibited here. Let us just regard this particular image as a metaphor for his masterful skill to capture a unique moment in time – his rare ability to understand nature and all contextual elements which are part of these huge canvases.

Colin can arguably be considered the reference when it comes to ultra-perfectionism in landscape photography. This is not only because of his extraordinary attention to composition. Beyond that, it is his perception of light and how it interacts with the natural world which results in images that have an almost tangible, dynamic feel. Moreover, what is striking is his capability to capture the authentic spirit of place, and by doing so, his place within that place. He offers some of the most natural interpretations of a landscape. And, as we all know, this is so hard to achieve. Par excellence, nature opposes any means of control. And that includes arranging elements. We need to move around to organise chaos and transform nature into the beautiful composition that awakens in our mind. Studying his images with care makes you realise what is important in landscape photography, and what is indeed trivial.

The Sublime Landscape

When writing about the Sublime it’s first necessary to establish what we mean by it. In contemporary speech, sublime is often a slightly elevated version of delightful, or delicious, as in, “You look sublime in that dress/suit,” or, even more annoyingly, “The profiteroles are just sublime, darling!” This is an undignified home for a word which in its artistic origins was used to distill the awe-inspiring, life-threatening, edge-of-catastrophe thrill of nature’s power and beauty.

The philosopher Edmund Burke who defined the idea of the sublime understood the importance of people being made to feel small and insignificant as a way of putting daily life in perspective, and to counter the inflation of the ego. Religion is one of the ways that this could be achieved, and art was another. But nature was/is Sublime’s source.

(For those seeking something more scholarly, there is endless interesting material on the Sublime in libraries and on the internet, as always.)

Arched Iceberg Greenland

All icebergs are ultimately doomed, and when they are as delicate and fragile as this one their demise is near. So near, that just a few seconds after this photograph was taken the arch collapsed, scattering shards of ice as dangerous projectiles either side of the impact zone. Luckily for us, we were not in the line of fire.

Arch Berg Collapse Greenland

Not long after, the remains of the decaying berg collapsed again in a less spectacular version of the arch fall. We remained safe, but it was a sobering moment. Undoubtedly a video of the event better helped describe it than any still photograph could.

To have a close encounter with a hurricane/tornado/erupting volcano/avalanche/earthquake/thunderstorm and survive, was to have a sublime experience.

Lockdown Project

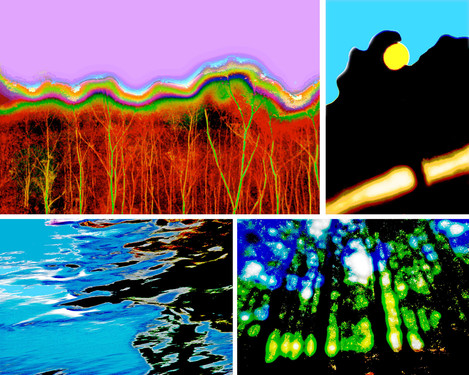

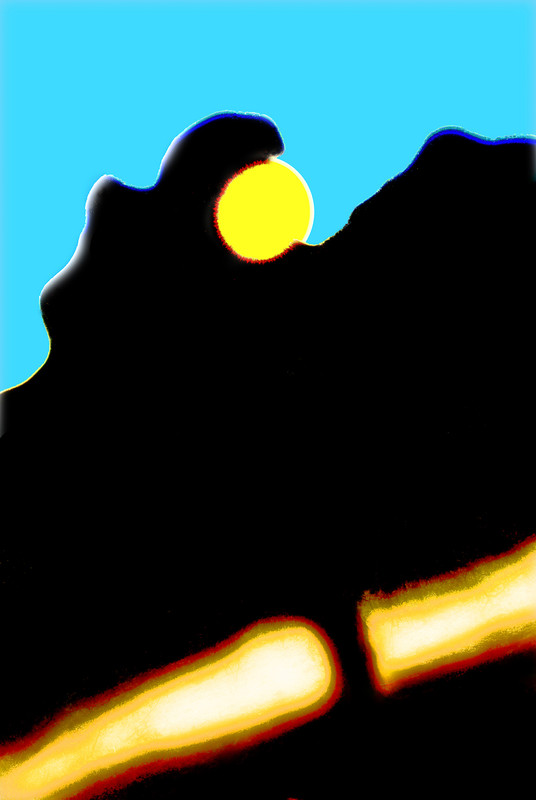

A few weeks ago, during one of our lockdown podcasts, I challenged Joe Cornish and David Ward to take a few photographs as a 'mini lockdown project'. The idea was to produce a set of four photos on any subject matter but that had to be taken inside your house. We also opened the idea up to our readers to have a go. The idea was definitely not meant to be a real 'competitive challenge' but to motivate us into picking up a camera, if only for a short while. With the lockdown relaxing in England (and possibly in the devolved nations in the next week) we thought it a good time to edit them into together for your enjoyment.

Astrid Preisz

Shadows on the Wall

When Austria started its lockdown in mid-March, I started to take photos of scenes inside my house - objects, reflections, shadows, abstractions. As a nature photographer, I look for the small things, the patterns of nature and always try to see the beauty in the mundane. As a lockdown photographer, I tried to transfer these principles to my house and found the shadows the sun cast on my kitchen and living room walls during different times of the day most enticing - the sun being the artist and the random objects in my house the props.

David Ward

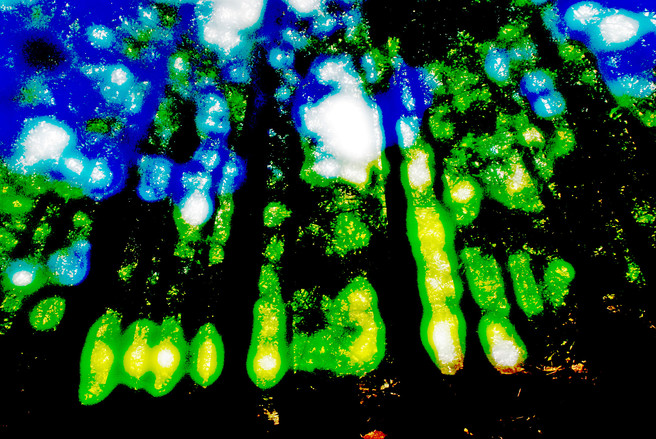

Colour and Luminance

I wanted to experiment with some intense colours on a high key field.

Ed Hannan

Kiwi

During this coronavirus lockdown period, I set up this wooden Kiwi model on my dining room table and added various other objects to try and put the bird into some kind of imaginary habitat. The images were made on my Nikon D800e fitted with a Sigma 150mm f2.8 macro lens and lit with Bowens studio flash.

Graham Cook

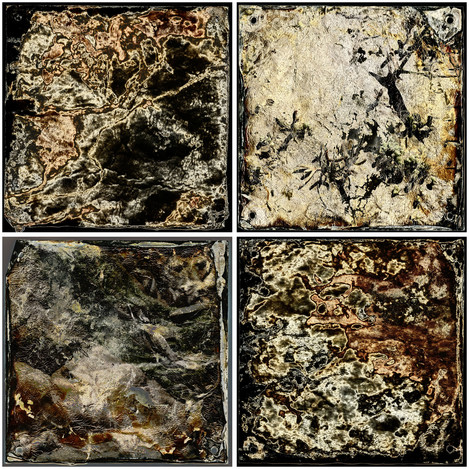

When a home is not a home

There is nothing conventional about how my imagination views our home. It is very much like a Time Machine, my very own Tardis - often I’m travelling through space or finding myself surrounded by microscopic detail from the natural world. For some years I’ve been cooking up abstracts for what’s become known as my 'Kitchen Collection’. It has opened my eyes to another world, one that’s created through looking at things differently and responding to the unexpected or inconsequential. The consequence of cooking, of opening a store cupboard, freezer door, dishwasher or refuse bin is never dull, it’s always tinged with excitement and expectation as I’m never sure where in our universe I may end up. The four images are simply representative of that journey, all iPhone and processed in Snapseed. As ever, no explanations, but they do or did exist in and around the kitchen.

Ian Meades

Bringing Outdoors Indoors

My wife is a fibre artist and our house is filled with the materials of her craft - this includes dried leaves, seedpods, rusty bits of metal, small tree limbs in various states of decay... So with a bit of hunting around, it was relatively easy to photograph things that one would normally find outdoors, in our indoor environment. With the added advantage of being able to do at least some of it in my pyjamas.

Joe Cornish

Anxiety

Hand-washing is one of the most obvious symbols of our current predicament, lots of it, and especially after every excursion into the world beyond our front doors.

Daydreaming

A strong memory for me of the crisis is our son Sam being at home, a joy for us, and a highlight is to hear him improvising on the piano

Homegrown

We have eaten extremely well during the crisis, much of it from our garden; Jenny has nurtured our asparagus plants devotedly for several years now.

Mourning light

The view through a window is meaningful to many and although we are so lucky to have a garden the sense of virtual imprisonment in our homes can be hinted at by the window. I also associate windows with Matisse and Derain, two of my favourite painters… and still-life and windows seem essential. I have lost several good friends during this period, although strangely, none to coronavirus; the title also refers to that.

Kaare Selvejer

Shells

The pictures were all made with old manual focus Carl Zeiss 120 mm F 4 APO Macro Planar (for Contax 645). The shells were placed on a black glass plate in my living room using ambient light from a window softened by a white curtain and a piece of white cardboard as a reflector.

Lizzie Shepherd

The Senescence Of Tulips

Tulips have long been one of my favourite flowers to photograph - they have a certain elegance throughout their lifetime and, it seems when all signs of life are long gone. These tulips are from the last cut flowers I bought - just before lockdown. Originally I planned to document their blooming and gradual demise, only to find that their demise lacked the usual elegance. However, several weeks later, they had one last gift to give and several of the flowers were looking wonderful in their deteriorated state. Above all, it was their texture and translucence that piqued my interest and at last, revived some feelings of creativity. I've taken a whole series of them, in various poses, some single, some as pairs, sharing a last slow dance. All shot with natural light, backlit by a bright (but draped) window and with the odd reflector bouncing light back onto the flowers.

Madeleine Lenargh

Home Portraits

I started this series back in March when we went into lockdown. Frustrated, because my favourite landscape location was closed to the public, I started noticing how the play of light, shadow, and reflections transforms familiar objects in the house. The project became a way to share with others how you can view ordinary things with new eyes.

Robin Jones

A Beach in a 16x12 developing tray

I have been keeping occupied during isolation by learning to make Cyanotypes and it was while washing out a print that the idea came, to make a seashore in the developing tray. I had used the same tray just a few days before to wash some shells for an earlier image idea, but 4 related images called for something more ambitious. The idea was for the "tide" to come in, with the help of a hosepipe and to show the backwash and the shell beach both wet and then dry as the tide went out.

Steve Williams

Lockdown Studio

Taken in my 'home studio', in truth a simple background of white card on my dining table, lit from the side via a big window. Sometimes I use off-camera flash via a remote, but I try to use natural light with silver foil reflectors instead. Plants are from my garden - mainly weeds. I'd always want to try some macro work and this enforced social distancing and 'stay at home' has given me time to do it at last.

Tim Parkin

Barred

I was thinking about was missing during lockdown and I collected a few items together that represented them. The glass was the invisible limits (and also the thing I was drinking out of when I came up with the idea). I was trying to use random backgrounds from the house but with my iPad in hand, and a quick experiment with a tilt-shift lens, this came about.

Viv Davies

Tracing a Path

Every morning - sunny ones at least - the sun traces a path across the staircase in my house by means of a patch of orange projected light. During lockdown I have watched the locus of colour gradually shift as the sun's path shifts towards summer. But it never reaches the mountains beyond. The colour is a result of a decorative glass plate sitting on the windowsill above. The mountains - a watercolour of Glen Nevis painted by a good friend.

David Cole

Road Signs

And we had one more entry that wasn't indoors but we liked it so much we let David Cole off...

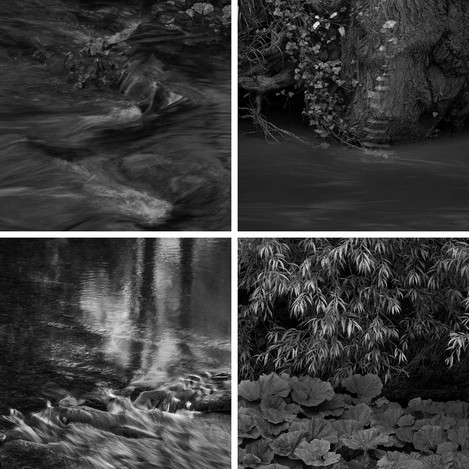

Frederic Demeuse

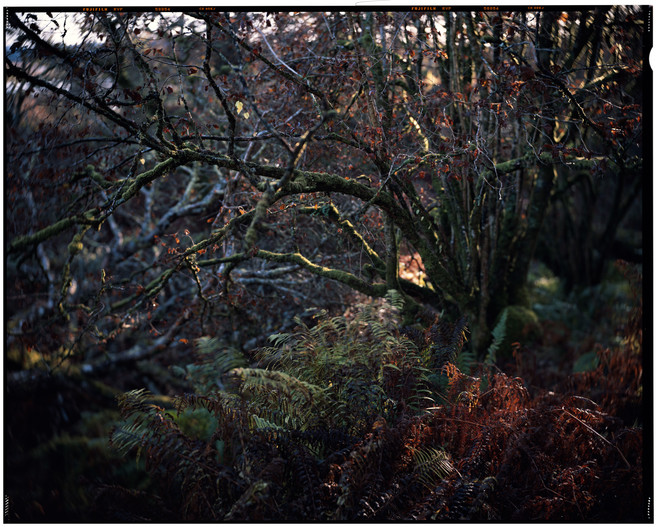

Frédéric’s interest in, and study of, ethology and ornithology shows in his images. Instead of an empty landscape, he shows the animals, birds and insect life of the forest in its setting. He’s an advocate for nature and its restorative effects. When we think of rainforest, we frequently do so in the context of tropical or sub-tropical regions. It’s easy to forget that there are temperate rainforests too and that these are just as precious and just as vulnerable. We even have our own remnants of Atlantic rainforest on the south-western fringes of Scotland (and having spent time in it in the rain, I can vouch for the fact that ‘rainforest’ is not a misnomer). While many of his images are in colour Frédéric also likes to work in black and white, enjoying its ‘soul’, so we’ve included a number of monochromatic images with an emphasis on mood and texture within and without the trees.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself – where you grew up, your education and early interests, and what that led you to do as a career?

I was born and raised in Brussels where I still live. I was lucky to grow up in a neighbourhood next to the Sonian Forest, the green lung of the European capital. My childhood home overlooked a large wood of several hectares (now classified as a Natura 2000 reserve) where I made my first observations as a naturalist. Squirrels, amphibians and newts of the small pond, birds at the feeders in winter. I quickly became passionate about ornithology, a passion that has never left me. From an early age I devoured naturalist books and magazines. My field guides about birds never left me and each family trip and vacation gave me the opportunity to discover new species and new biotopes. Around the age of 8-9 years, I took my first pictures of robins, tits of all kinds (the crested tit was a favourite), nuthatches, wrens, woodpeckers, finches... I had fun recording my observations on the computer. But I never figured out that photography and nature would take on such importance until much later in my personal and professional life...

How did you first become interested in photography and what kind of images did you set out to make?

I made my first hides in my garden - the great spotted woodpecker was by far the most eagerly anticipated bird! It was, therefore, my passion for birds that led me to photography, probably motivated by the need to keep track of my observations. At the age of 12, I received my first serious equipment, a Nikon F401 film camera with a 300mm lens. A few weeks later I fell from a weeping willow into a pond near my home while trying to photograph a couple of great crested grebes…

It wasn't until around the age of 25 that my early interest in photography resurfaced in my life. At that time I was passing my final qualifications to become an airline pilot (my passion for birds probably made me want to fly like them) but an accident put an end to this career that had been set for me. Passionate about extreme skiing, I fell heavily while jumping over a rocky barrier because of a misidentification of the track. It was a big blow because I was no longer physically able to take the commands of an aeroplane, mainly due to a loss of sensitivity and motor skills in my left hand. But in hindsight, it was a great chance to return to my first passions of nature, forests, and the animal world.

I then worked in an office specialising in real estate acquisitions, but one Monday morning I resigned because I realised that it was much more interesting and fulfilling to run through the woods and to chart your own course. I found no sense in spending time in a job that I did not like; in fulfilling objectives contrary to the interests of the planet, the biosphere, our survival... A dog shared my life at that time and thanks to many walks I rediscovered the Sonian Forest which became almost my second home as I spent countless hours exploring every corner and focusing on different subjects over the seasons. Wildlife photography, landscapes, but also a lot of macro.

The Way We Were

We’re on some surreal timeline just now, deserted streets, empty malls, closed bars, cafes and coffee shops. Even the landscape we once worked and played in is essentially inaccessible to us. So much of what we took for granted is now a luxury we can only look back on and reflect. Maybe the person I was isn’t the person I should be, perhaps my attitudes weren’t always as noble as I would like.

From the cage, the horizon is infinite.

Today, Ann Kristin and I drove to Fort William for the first time in a month. It was quite the trip, having only been within walking distance of the house since mid March. The rush of driving along a road at 60mph, the vistas that used to be just passing by, now appeared intensely interesting. A herd of Red Deer grazed low in the glen, and as we sat waiting for the ferry to arrive, 6 Black Guillemots were engaged in heated territorial squabbles on the deserted pier. For certain, the deer and the birds were both there because, on the whole, we aren’t.

The road was deserted, save a few people like us, making essential trips. A far cry from a usual Easter Holiday weekend when the roads would be packed with excited tourists and frustrated locals.

I had a deep and moving notion as I noticed nuances of light on a distant hill, big patches of snow looming as the view opened down to Glencoe. Our thoughts rested on our dear friends Tim and Charlotte (I think they read these articles!) - all the plans we had to go climbing together, curry nights and just hanging out and laughing. As someone accustomed to studying the landscape, I was looking at it with fresh eyes, suddenly aware that without a camera in my hand I was looking for the sake of looking; feeling, engaging, fascinating, imagining and being inquisitive.

It’s Up To You What You See

Abstract art can be the most frustrating of art forms, but it can also be the most rewarding. There is a simple reason for this I think: the responsibility for finding ‘meaning’ in an image is thrown entirely on to the viewer. Rather than being presented with a depiction of what the artist saw, we are asked to see completely for ourselves. Most ‘realistic’ photographs make cognition easy: the subject is recognized and the viewer’s reaction to that subject is mediated by the photographer’s treatment of that subject. When we move into the realm of abstraction, however, that link to reality is broken - which of course seems particularly perverse in a medium such as photography which relies so emphatically on the object being photographed. And with truly abstract images meaning is no longer literal, there is no correct interpretation. Humans always seek definition, solidity, coherence, so abstraction runs the risk of frustration…

So how does abstract art become rewarding? The trick, as a viewer, is to relinquish the desire for meaning, or rather, to allow the mind to wander, to see relationships between form, colour, pattern, tone, texture etc, and to take pleasure in these relationships for their own sake. This can imbue an abstract image with an emotional charge which can be hugely pleasurable. Stieglitz is perhaps the earliest exponent of this with his Equivalents series from the 1920s when he photographed clouds but deliberately didn’t include the land so that they were void of reference points. No internal evidence to locate them in time and space. Stieglitz intended for them to function evocatively, like music. Emotion resided purely in their form, and it’s up to the viewer to feel their way to their own emotional interpretation of the images.

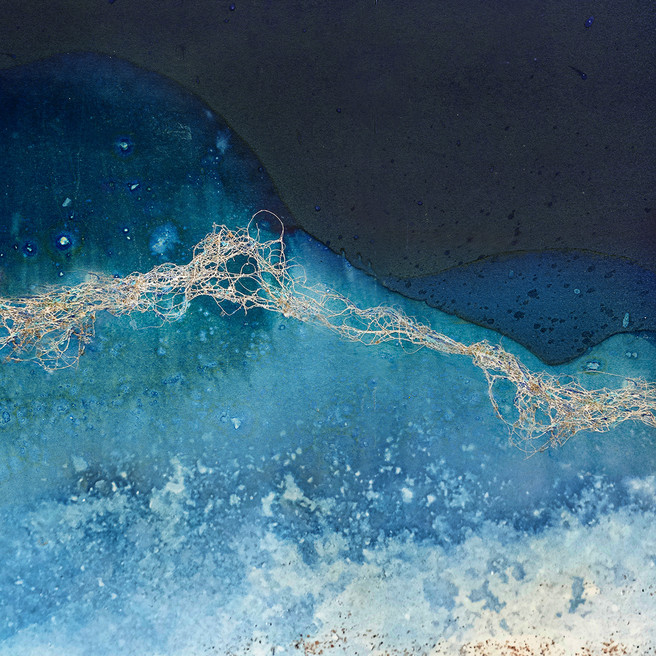

How does this work when we view an image such as Marianthi Lainas’s Tidal Traces #4? It is certainly abstract – there is no grounding in reality, no clear link to an object. Not only is the subject matter unfathomable, but the medium itself is also open to question. Is this actually a photograph? We don’t really know. (On her website Lainas explains that this is a cyanotype using light sensitive papers on the strandline, exposing them to the seawater and sand, and then selectively incorporating other media into the images). But what gives this image its beauty is, I think, the intrigue it evokes in the viewer specifically because it has no link to reality.

My own personal reaction to the image was first to see shapes that did have an echo of the landscape. So I noticed the delineation between blue and orange which suggested a horizon line.

As I look at the image, I am able to hold all these readings of it in my mind at the same time – the desire to impose a literal reading plus the pleasure at just looking at shapes and colours and noticing contrast and similarities. Perhaps this is why Marianthi’s abstraction is so powerful because it allows the viewer not only to see what s/he wants to see but to do that on a multitude of levels, all at the same time…

Below is another from the same series. I see the coast, space, sea spume, colour contrasts, lines vs shapes and on, and on. How rewarding is that…! What do you see? For more of Marianthi’s work see http://marianthilainas.com

Love Dandelions

My passion for the planet has for a time refocussed on compassion for humanity. COVID 19 has us frightened for family and friends, has us watching bewildered as we observe the best and the worst of mankind and has us struggling to understand. Originally, I had drafted this article as my response to Ted Leeming's and Morag Paterson's questioning our responsibilities as Landscape photographers. I had written about the difficulty of making tough decisions in order to live sustainably. It now seems this is being forced upon us and we have an opportunity to reshape how we live.

However hard I tried to reduce my environmental footprint I realised I was still part of the problem! What more could I do? I asked is it worth it? We are living in a world where the USA permits new drilling for oil in the pristine Arctic, (Carter, 2019) where China has negotiated extensive coal mining in Africa (Obura, (2017) and where Brazil's government 'shrugs off' the burning of the Amazon rainforest (Hockaday, 2019). We live in a world where populations are pushed into extreme poverty needing cheap food and clothing (Nixon, 2011:40), a world where multinational corporations not only commit massive environmental degradation (ibid) but also send out enticing glossy advertisements tempting me with even faster camera lenses and 'high tech' fabric to wear whilst waiting for the golden hour. Yet locally, a group of youngsters plan to clear plastic from Orford Ness shores (see fig 1 & 2) and another group plan rewilding patches of land in Ipswich. I too need to believe my own actions can help reverse the processes which are taking us to a global climate tipping point.

Although I am less and less enticed to buy new equipment, I still need to question the carbon cost of my photography …. especially those taken in faraway places. Whether it is 400 miles return to the Peak District or 4000 miles return to the Arctic where I toured a couple of years ago (see fig 3 & 4) or the 12000 miles to the Galapagos, my cancelled photo tour booked for April. As I learn the high climate cost of air flight, even with 'offsetting', I ponder more and more about the carbon footprint dilemma of landscape photographers who love all that is beautiful on this planet.

Over the past two years, I have been researching the science, politics and economics behind the underlying tensions and resistance to climate change. I have been asking what does this mean for the photographer? When I voice my concerns, the responses are very much about the hopeless task in a world which is governed/controlled by those listed in my opening musings.

Photographers have a global perspective and we care intensely about the beauty of the landscape. We also know our own localities as well as anyone. Could we be a powerful force to encourage local sustainability? Everywhere there are small parcels of important ecological niches under threat. It was the rate of loss of salt marsh along Suffolk coastlines, as important to the world's ecology as the Amazonian rainforest, that started me on a local photographic project. I explored my perspective of ecology and buried my prints for 10 weeks (see below). I spent hours in the salt marsh recognising what is at stake which gave me the courage to write this. I got very muddy but returned home a different person.

This was my final photographic degree project, after 7 years of study with OCA. At age 70, which now has a new significance, I realise I am rather late to emerge as an artist (new graduates are called emerging artists so I found out recently!), but I may not be too late to start a discussion.

With my time speeding up I offered to share more about my own project at the 'Meeting of Minds' On Landscape Conference 2020. I have also been thinking what next and how could landscape photographers act locally but link together to increase our impact. Could we use our creativity and skill, our dedication and commitment, to raise the profile of specific issues and/or might we link in with the scientists from Wildlife Trusts, conservation bodies and local universities? There are numerous studies evidencing how artists raise the impact of scientific findings.

Here is an idea for a shared photographic project to while away our summer days close to home! I read about the importance of 'leaving the grass to grow 8-10cm (3-4in) tall which means clovers, daisies, self-heal and creeping buttercup can also flower.' (Weston, 2020) The article went on to cite Memmott 'You can’t personally help tigers, whales and elephants but you really can do something for the insects, birds and plants that are local to you,' (ibid) The global mass of insects is falling by 2.5% a year and 40% insect species are threatened by extinction within a few decades, according to a global scientific review last year. (Sanchez-Bayo, 2019). We have all heard how bees are essential to our survival.

Rather than spending our extra time at home tidying the garden, could we look to see how we can help sustain the survival of vital creatures? By default, last year, at home I did less mowing and was amazed at the increase of insect and birdlife. (see fig 7 & 8)

Could we pull together a portfolio of our landscape work – both wild and cultivated - showing the benefit of letting flowers bloom and seed heads ripen? Our photographs just might encourage less mowing, less highly trimmed gardens and parklands and wilder local verges in the future. Could we encourage all to love dandelions? Dandelions, which have just begun flowering, are rich in nectar and the early food for bees and butterflies. What do you think?

In time I am hoping to set up an East Anglian ecological art resource and approach environmentally aware organisations to offer an 'art for science' service ...whether this will work we shall see! But I would very much like to learn from anyone who has done anything similar within their community. It is likely to be a tough and sometimes disappointing road but do I have a choice? As Dr R. Macfarlane wrote in 2016,

We are living in the Anthropocene age, in which human influence on the planet is so profound - terrifying - it will leave its legacy for millennia. Politicians and scientists have had their say, but how are writers and artists responding to this crisis? (Macfarlane, 2016)

References and Bibliography

Curtis, D. J., Reid, N., Ballard, G. (2012) 'Communicating Ecology through Art: What Scientist Think" [online] https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss2/art3/ (Accessed on 8 October 2018)

Demos, T.J. (2017) Against the Anthropocene Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Carter, L. (2019) 'BP backs Trumpo's Artic oil drilling plans despite climate risk'. In: UNEARTHED [online] https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2019/05/19/bp-arctic-drilling-climate/ (Accessed on 17 February 2020)

Hockaday, J. (2019) 'Amazon rainforest still burning despite ban from Brazil government.' In: Metro News [online] https://metro.co.uk/2019/09/04/amazon-rainforest-still-burning-despite-ban-brazil-government-10686406/ (Accessed on 17 February 2020)

IPCC. (2018) Global Warming of 1.5degrees [online] https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (Accessed on 17 March 2020)

Klien, N. (2014) This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs The Climate. New York: Simon & Schuster

Macfarlane, R. (2016) 'Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet forever.' In: The Guardian [online ] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/01/generation-anthropocene-altered-planet-for-ever (Accessed on 17 March 2019)

Nixon, R. (2013) Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge USA: Havard University Press

Obura. D, (2017) 'As China has boosted renewable energy it's moved dirty coal production to Africa'. In: QuartzAfrica [online] https://qz.com/africa/1087050/china-moved-coal-production-to-kenya-with-risky-environmental-impact/ (Accessed on 17 February 2020)

Sanchez-bayo F. (2019) 'Worldwide decline of the entomofauna' In: Science Direct [online] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320718313636 (Accessed 14 February 2020)

Weston, P. (2020) 'Help bees by not mowing dandelions'. In: The Guardian [online]

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/01/help-bees-not-mowing-dandelions-gardeners-told-aoe

The Value of Things

I'd never really had the confidence to think of myself as a landscape photographer, even though taking photographs of landscapes had been part of my job for years. It took tragedy, a process of maturation, and several pairs of worn-out boots to find a path to self-expression in what many would consider a bland and very agricultural part of the UK.

Nowadays, many jobs – especially creative freelance ones – involve elements of professional photography but not the whole package. That's certainly been the case for me. I've been a regularly published outdoor writer since 2015. When I submit a feature about backpacking or mountaineering, the editor expects quality photographs that document the trip and illustrate the story. I soon optimised my photography for what editors want: obvious mountain landscapes with a human element and composition that would make a good double-page spread.

There never seemed to be anything of interest to photograph in my local Lincolnshire countryside. At the time, landscape photography was all about 'epic' mountain scenery and maximum drama.

While I love the photographic side of my job, it didn't take long for me to figure out that I was rarely creating images for myself. I didn't know how. I was working to a brief, and because this side of my career began to take off in parallel with my development as a photographer, I never got the chance to figure out what my own vision was beyond taking pictures that looked 'good'. Did I have anything of personal value to say with my images, or were they just illustrations?

I'd had some positive feedback, and I knew that editors liked my photography, but I had no idea what it meant to me. By late 2017 I had figured out that validation in the form of likes on social media meant nothing. Although I didn't know it at the time, I was desperately seeking for an artistic vision.

Opportunity

In 2017 I began a new habit: I started to walk five miles each morning before breakfast. Over the months, this repeated immersion in my local area started to change my way of seeing. I noticed more. What had once been a bland patchwork of fields and scrubby woods became something entirely different. Slowly, a delicate enchantment began to illuminate this place.

Of course, light helped. My slot for walking was 6.30am to 8.00am. At certain times of year, I'd catch the sunrise, and I started to learn where the Belt of Venus would fall, which sections of my walk spoke to me in different ways. I carried my camera, but it took time before I started to capture anything more than visual experiments.

One particular dead tree I passed every morning stood out as an obvious subject. This grand old staghead, isolated in the Gunby parkland, delighted me with its various subtle moods. It soon gained the nickname of 'the Poet'. I realised early on that I wanted – needed – to say something about the Poet, but I didn't know what it was communicating to me, and that's why early attempts to create an image at this spot were failures.

As I learned to listen, I started to see the potential for personally meaningful images here. Something was missing, though. Hundreds of miles of hiking through this small patchwork of woods and fields, over a long period, had given me the fuel I needed, but I lacked a spark to ignite it.

Grief

In February 2018, tragically, I lost my dad to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A lot changed for me and my family during his long illness. Before his death, I struggled with anxiety, flirted with burnout, earned my first grey hairs, and asked my girlfriend to marry me. Afterwards, I felt like a completely different person.

It's no coincidence that I created the first personally meaningful image of the tree I called the Poet one week before my dad's funeral. The so-called 'Beast from the East' had carpeted Britain in deep snow that February. In its aftermath, I'd gone walking in the Gunby estate with Dad's old Spotmatic loaded up with Fujifilm Superia 400, and as I studied the Poet something seemed to click in my head – a harmony of my familiarity with this subject and my renewed perspective.

I knew what it was telling me now. It was telling a story of infinity and ephemerality, of isolation and connection, and a frank, unsettling look directly into death's face. I'd been walking past this skeletal form for so long without really thinking about the fact that it was a dead organism, braced against every passing gale, casting shadows and soaking in rain, etching patterns against the sky, whispering verses to passing walkers. Dead but very much alive. As I began the long process of sorting through my father's photographs and writings, this resonated with me.

This moment with the Poet was the catalyst. A personal maturing had combined with photographic opportunity to change how I saw this landscape.

Looking for the glow

I planned two more images of the Poet that express some element of what this subject means to me.

The first, 'Summer swift', was captured after several weeks studying the swifts that would perch in the Poet's upper branches. I wanted to capture a swift soaring at the tree's uppermost apex against broad brushstrokes of cloud, preferably in light that showcased the interesting textures on the branches. I succeeded in August 2018. To me it speaks of hope and rebirth – again, it's no coincidence that Hannah and I got married three months earlier – and maybe also something about this subject's remarkable breadth of emotion.

The second, 'The Poet, embracing infinity', had been previsualised more or less since that first image of the tree in the snow. I wanted to capture the tree against the Milky Way – an otherworldly form, again representing permanence while accentuating the subject's more alien and unnerving qualities. I light-painted with a green torch during the exposure to add detail to the trunk and shift the mood.

Since then, I've begun to collect images that might be considered riffs on a theme. My subjects are almost always trees. I look for ephemeral light that infuses an otherwise ordinary landscape with fleeting magic, and I often seek to render the organic components of the scene as stark silhouettes, playing with structures and framed skies, looking for hidden portals and pathways. There's nothing original in this, of course – better photographers than me have been doing it for a long time, but this has become the way I interpret a landscape others might consider dull. There's so much magic here.

I am trying to say something about fragility and vulnerability too. Not just my own, but that of the landscape itself, which is threatened by development and habitat destruction, and all the more so because most assume there is nothing of value here. A wood I walk through each morning was partially bulldozed in early 2020. This affected me more than I thought it would. The images I've captured in this place can never be recreated.

The path ahead

Even now, I struggle to think of myself as a 'proper' landscape photographer. Most of my mountain images are still created to a loose brief, although I have begun to find a more expressive way of doing this. It still takes effort to put myself in that more contemplative frame of mind required to create images for myself alone. Crucially, I feel that I am breaking away from trying to recreate images I've seen online, because I don't particularly care whether others see technical perfection or artistic merit in these photographs – they're about fulfilling a need within me, not seeking approval or meeting external requirements.

That said, I am becoming more discerning as I seek to improve my skills. Technical merit is a side I've long ignored because I saw it as largely irrelevant. Being agile and capturing emotion are more important, but achieving higher technical standards will be my next area of development as I seek to improve my composition skills. In the mountains, it's all about keeping kit weight down and capturing the images I need at a good enough level of quality without breaking the rhythm of my hike, but I can afford to be more deliberate for my personal work. As I grow and learn, it's my hope that my artistic vision will become more refined too.

Two years after my dad's death, the Poet withstood Storm Ciara, which brought winds of over 70mph to the Lincolnshire Wolds. Not a single branch on the old tree was damaged.

Lockdown Podcast #5

We finished our reader questions in the last Lockdown Podcase and so in this episode, I thought I'd ask about composition and whether Joe and David thought it was possible to teach, learn and how they go about it. We had a wide-ranging conversation and a few recommendations of book resources at the end. We hope you're enjoying the podcasts as much as we're enjoying making them.

There & Back Again!

I've always loved the theatre. There is a minimalist approach to portray everything. The approach is like an ideograph as the theatre, film and opera director, Julie Taymor, puts it. An ideograph is like a brush painting, a Japanese brush painting. Three strokes, you get the whole bamboo forest. In her most famous work, "The Lion King", she uses the essence of the story. The circle. The circle of life. Very effectively. Ever since I saw the nineties Disney movie, "The Lion King", I have been hooked. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to make images, still or moving, that evoke emotions? is the question I’ve asked myself often.

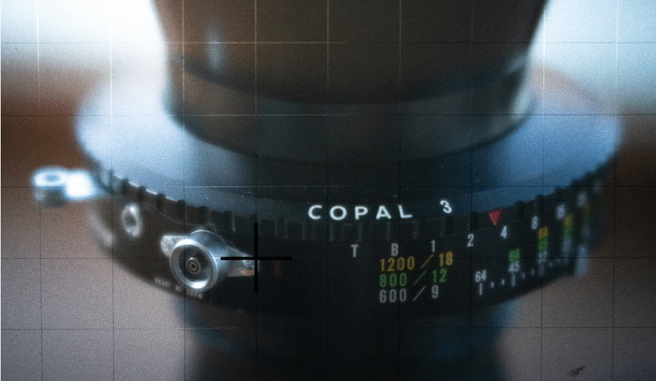

I knew, someday when I'm able to afford it, I will buy a camera and start making images. And so, it all started when I got the Kodak KB 10 from my first salary of being a graduate engineer. It was fun. Of course, buying a film and developing it for small prints was still a luxury. I had it for a couple of years and kept making images. Most of them could only evoke emotions or memories for myself. And that is okay. I think. I moved to Germany as an exchange student on a decent scholarship and that KB10 became a Canon 500N. I eventually got to know about the “larger film” cameras.

Over the next 4-5 years, I moved from 35mm to 120 (Mamiya 645/Pentax67) and then to 4x5 large format. It took a lot of courage and saving to invest in the large format system. But there it was, my precious Tashihara 4x5 with the only lens for it, the 150mm Schneider. Unfortunately, while making a photograph in Harz national park near Göttingen I slipped over a mossy boulder. In the panic, I decided to hold onto the next standing thing. My tripod. Both of us took a slide I will never forget and ended up in the cascade. The lens and most of the wooden parts were broken and I could never muster the courage of buying another large format camera. In fact, for over a year all I was using was a Yashica Mat 124G which I bought in a German Flohmarkt (Flea market) for some €30.

Well, this was 2005/6 and Canon had released their shiny and able EOS 5D. It was way out of my budget so I was happy to stick to the film media which was incredibly cheap compared to today’s standard. I mean, I used to pay €1 per 120 roll film development in Sauter, München. That soon changed though. And I eventually succumbed to the “dark side”. I bought a digital SLR and it became my main camera for all things photography, family, portraits and landscape included. My research institute was also selling all the “old” equipment including some really fine Hasselblads and I bought one for a really small amount. I was having buyer’s remorse for a couple of years but never sold it. It stayed in the pelican case it came with for years. Fast forward to another 10 years or so and while going through all the remaining moving boxes I found that case with many rolls of Ilford Pan F film. Around the same year, I was also thinking about my ever bulging lightroom catalog. Agreed that the majority of it was personal family images however, I did make quite a few landscape images with various digital SLRs I had kept buying in search of a silver bullet.

The fact was I had lost the mojo and the enthusiasm. It had become an automated process. There were few decent ones I could have printed, which is my litmus test for a good image still, however, the percentage was really low single digits. I was also hearing a lot about film resurgence. I was very sceptical though as most of these were “YouTubers” who I thought wouldn’t exist in a couple of years. Most of my heroes - Joe Cornish, Guy Tal, David Ward and many more had moved on to digital.

Issue 205 PDF

End Frame: ‘Hrafntinnusker Fog Ice River’ by Bruce Percy

I missed the 2016 Meeting of Minds Conference so I have only been able to watch Bruce Percy’s talk on YouTube. I had stumbled upon his work on-line, possibly following up on the many mentions he gets from other photographers in On Landscape and became an instant fan.

There are very few of Bruce’s images that I do not get a lot of pleasure from, not to mention the learning and inspiration they provide. He clearly takes great care in setting up his photographs in the field but, as he says, he does not like the term ‘post processing’ but sees the darkroom, digital or otherwise, as just another element of the image making process. His care and skill in subtly managing and manipulating the range of tones and colours in an image make a huge contribution to the success of his pictures. As does the way he guides the viewer’s eye around an image with curves and diagonals. I find myself increasingly interested in the design of images and the way their visual elements, in terms of shapes, colours and tones interact to affect the viewer’s experience and perhaps this is why I find his work so compelling.

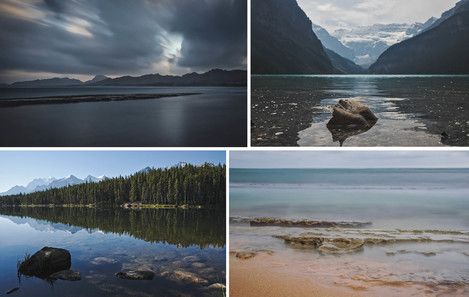

Subscribers 4×4 Portfolios

Welcome to our 4x4 feature which is a set of four mini landscape photography portfolios submitted from our subscribers. Each portfolios consisting of four images related in some way.

Submit Your 4x4 Portfolio

Interested in submitting your work? We're on the lookout for new portfolios for the next few issues, so please do get in touch!

If you would like to submit your 4x4 portfolio, please visit this page for submission information. You can view previous 4x4 portfolios here.

Anette Holt

Colours of Iceland

Justine Ritchie

Gorm

Mark Hunneybell

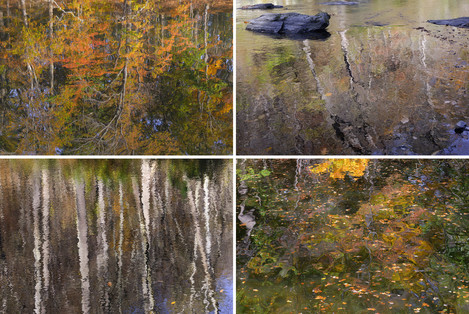

Broken Reflections of York

Philip Moylan

Touching the Surface

Broken Reflections of York

Recently I have lost my mojo so to speak for photography in general. I think a lot of Photographers go through this at some point in their journey. So to overcome this, I purchased a small walkabout camera and ventured out.

This set of images were taken in York (England) just after a heavy period of rain. I decided to take advantage of the newly fallen rain by looking for interesting reflections in the numerous puddles. I really enjoyed the challenge of finding the compositions and then trying to capture the images on my newly purchased camera.

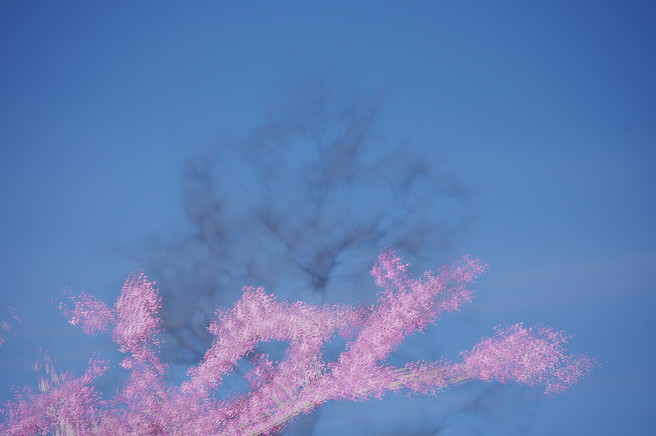

Gorm

The air is part of the mountain…as soon as we see them clothed in air the hills become blue. Every shade of blue, from opalescent milky-white to indigo is there ~From The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

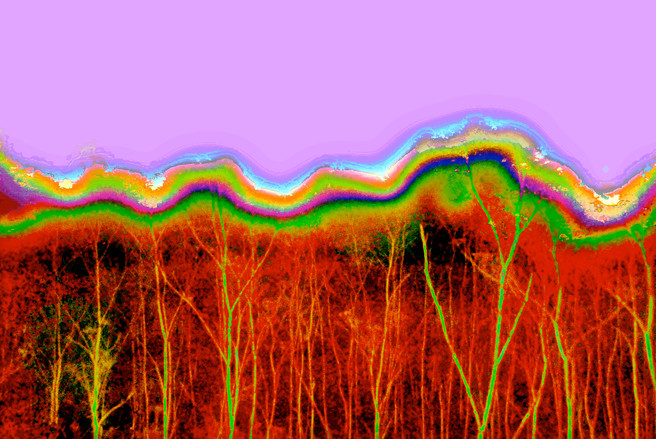

‘Gorm’ is the Scottish Gaelic word for blue - ‘Cairngorm’ meaning ‘blue mountain’. The light in this area bathes the landscape in a surreal array of blues as described in the above quote by Nan Shepherd who spent a lifetime exploring, engaging and connecting with this wild and inhospitable highland region.

This set of images is very much inspired by the above quote and has been created using in camera multiple exposures and ICM (intentional camera movement) techniques to reveal the area's unique spirit of the place by creating abstract representations of this beautifully bleak location and in particular what it felt like to be among the colours, contours and coldness of the Cairngorms.

Colours of Iceland

Iceland is a landscape photographer's dream with dramatic scenery and big skies at every turn. For me, the individual elements within the landscapes are just as fascinating as the big vistas. The details are worthy of a closer look in their own right.

I love the strong colours within the landscape, the yellow lichen growing on the hillsides, the fluorescent green of moss growing on wet rocks, the stark contrast between the black lava and the remnants of snow, the golden shimmer when a sunray hits the volcanic ash, or the different colour shades of the soil - ideal conditions for someone like me who loves in equal measures the outdoors and abstract and landscape photography.

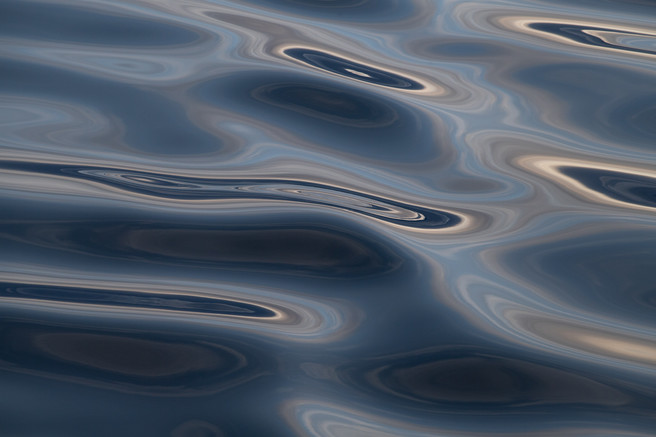

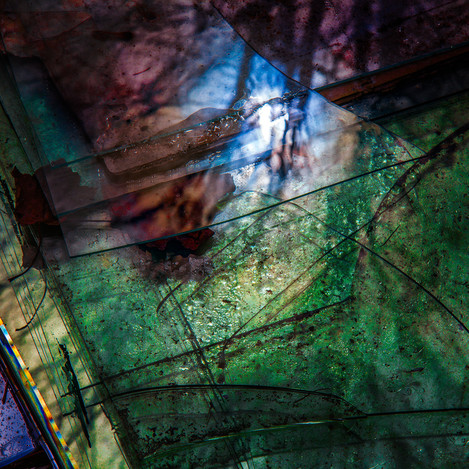

Touching the Surface

In my 40 years of surveilling for special locations to self advantage colour imaging, I happened upon several "sacred" places, temples if you will, which provided an opportunity for a wide colour gamut of reflected light on fluid surfaces. Stained glass windows, if you will. These are unusual treasures for the image maker as in a variety of seasons and lighting, they offer almost infinite variety with an application of specialised technique and appropriate visual acuity i.e., the ability to previsualize outcomes after assessing light, proper exposure, and the notorious nemesis, the wind. Why bother trying to obtain proper photos in such fleeting circumstances? The simple answer is the complex colour schemes which result that at times approach 2d abstract painting, even to a verisimilitude of brush strokes.

Thankfully digital tech allows for multiple images in short order, as outcomes do shift dramatically in nanoseconds, subject of course to the vicissitudes of wind impacting surfaces. Certainly, the direction, angle and strength of sunlight provides the diverse possibility in hues.

In my experience, the most subjectively beautiful effect is when strong "big blue" light at lower angle hits those natural objects surrounding and the informed light indirectly passes to the calm water's surface, as if one is knowing and viewing their god obliquely. A temple of exquisite beauty seen infrequently in fleeting moments (and I used to believe photographing birds was difficult).

The Path Towards Expression – part 3

In the last two articles of the series “The path towards expression”(see part 1 and part 2), I tackled the particularities of using photography as a tool of personal expression. As we saw, when a clear intent leads the way throughout the whole photographic process, we increase the likelihood of ending up with a coherent body of work that transmits concept, emotion and a clear message to the observer.

In this article, I will analyse a case study, using one of my personal projects: “Septentrio”. For once, the importance here will shift from the photographs (the end result) to the process and its coherence.

Even if most of the time we will work intuitively in the field, it is important to be able to consciously and rationally approach our work before and after it has been done. In these moments of conscious awareness and analysis, it is a good practice to identify our reasons to photograph, the underlying concepts, the emotional connotations we want for our work, the context in which it stands, its potential audience and how and where we want it to be disseminated.

Being able to “defend”, theoretically, conceptually, emotionally and artistically our work is one of the best ways to scrutinise its coherence, relevance and genuine character. As expressive photographers, we enjoy total artistic freedom. But with freedom comes the responsibility of choice. Being free means we can take any path we want, and that is why it is so important to know why take one path and not another, and how to remain coherent along the way.

Forcing ourselves to verbalise our reasons to make a certain body of work, and describe our intent, register, objectives and sources of inspiration allows us to “test” our work. If our work is more than a shallow visual exercise and not someone else’s work in disguise, we will be able to answer the three questions that according to Robert Adams a critic should ask: What was I trying to do? Did I successfully do it? Was it worth doing?

Introduction

The Post-Processing Debate, Part I:

What is Real? How do you define Real? ~ Morpheus

Few topics in landscape photography generate as much emotional debate as digital post-processing. The fascinating thing about the current debate is that it closely parallels a similar debate that occurred nearly 100 years ago. Since Guy Tal pointed out that many photographers are unfamiliar with the history of photography as an art,1 this article will discuss that debate, where it led, and what we can learn from it.

Historical Context

The highly technical craft of early photography made it inaccessible to the masses. Mastery of the mechanics, chemistry, and optics of large, heavy, bulky and expensive equipment, not to mention coating glass plates and developing them in mercury vapours, was practised by only a few. Many saw photography as a technical craft used to record the world, whilst others tried to establish it as an interpretive art. Regardless, the number of practitioners was limited; most people did not own a camera.

That all changed in 1888 when George Eastman introduced the Kodak camera with the slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.” Advertisements proclaimed, “No previous knowledge of Photography necessary.” Suddenly, overnight, anyone could take a picture and photography became a popular national pastime. Two years later, the less expensive Brownie camera democratised photography, reducing it to the snapshot, which further challenged the idea of photography as an art.

In response, professional photographers, who wanted to maintain control of “serious” photography, developed advanced techniques whilst making the exposure, as well as during developing and printing. These techniques, which were beyond the knowledge and capability of casual photographers, included the use of soft-focus lenses, physically altering the emulsion, and replacing the silver halide crystals in the emulsion with oil-based pigments. The idea was to give the images an ethereal, painterly quality to mimic the higher art and was called Pictorialism.

A Pragmatic Approach to Colour Management

A few weeks ago Alex Nail approached me to propose recording a video with the goal of trying to explain colour management and provide some guidelines for photographers who may find the subject a bit of a challenge. We spent a while looking at different ways of demystifying the subject and coming up with some broad recommendations. We had a bit of a technology nightmare in the process but I think it probably helped us rehearse the topic well. There will be a second instalment coming soon where we answer a range of questions submitted by our contacts.

I've included a comparison photo showing the two rendering intents we talk about in the video with circles showing places that demonstrate the differences. A big thanks to Alex for driving this and editing the final video! If you have any questions, they might be answered in the next video but drop them in the comments below anyway.

Lockdown Podcast #4

We put a call out for question for our third lockdown podcast with Joe Cornish and David Ward. We managed to get through half of the questions last time and this issue we managed to complete the set.

As mentioned in last episode, we are looking at having a mini 'in your house' photography challenge. All three of us are going to give this a go (me and David have done something, Joe is still cogitating) and we invite anybody else who wishes to take part to submit some work. The deadline will be Monday morning and the only rules are that it has to be inside your house, not in your garden or out of a window.

We also mentioned last time that we're having a mini book club chat next week where myself and David Ward are going to talk about Edward Muybridge, in particular the book "Motion Studies" and me and Joe Cornish are going to talk about Robert Adams book "Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defense of Traditional Values". We'll be discussing these in a weeks time, starting with Robert Adams, if you'd like to read them and ask us questions about them, please let us know.

Meaning, C19 and the Voice Within Our Landscapes

The Earth is talking

Go & listen…

…the voices from storms have been talking for millennia.From ‘Earthwords’, a poem by Alisa Golden.

Each of us, through our uniquely individual landscape photography, offer our viewers a window into the soul of the earth and the messages it has for us about ourselves and our wider world.

Finding how we can best articulate what we want to say through our landscape work isn’t easy though because it makes us ask ourselves tricky questions; ‘why am I photographing this? What is it saying and what does it mean to me and the viewer?’

I believe this is a line of enquiry well worth the effort though. For it helps us consider how we might express something on any number of ideas, subjects, themes or concepts through our landscape photography.

The Lake District is where I enjoy exploring themes of the sublime and picturesque as I follow in the footsteps of both paint and photo heroes of mine. It’s life affirming and exhilarating to enjoy this scenery and my work embodies this thrill and personal pleasure. What it means to someone else is for them to decide.

After all, once we’ve figured out how to use a big stopper, how to compose well or mastered techniques like ICM or multiple exposures, the challenge for landscape photographers is to find and communicate something meaningful through our work.

Kyle McDougall

In this issue, we’re catching up with Kyle McDougall, who Tim interviewed for our Featured Photographer series six years ago. At the time, Kyle described himself as a landscape photographer and was finding himself drawn more towards the intimate details of nature. At the same time, he was happy to follow whichever path his photography took him on. There were, in hindsight, hints… Kyle talked about the importance of creating images for himself, of the experience, and of stripping ourselves of pre-conceived ideas and rules. Over the last three years, Kyle has pursued a more contemporary form of the genre, sparked by a year-long road trip across North America, and he now describes himself as being driven by a fascination with society, time, and our ever-changing environments. He’s also been working solely with film.

Our ‘Featured Photographer’ interview with you was published back in 2014 and there have been some significant changes in your photographic practice and output since then. We obviously want to talk to you in detail about ‘An American Mile’, but perhaps you can set the scene for readers by telling us a little about how you came to move away from nature photography? (You’ve referred to creative burn-out, and it taking a while to both get past this and to recognise that you needed to move on from those things that had previously held your attention?)

First off, thanks for inviting me back to talk about my work. And yes, a lot has changed since then.

In 2015, after focusing purely on traditional landscape photography for the previous ten years, I started to struggle to create work that I was happy with. It didn’t seem to matter what the location was, or how amazing the conditions were, my experiences and images were lacking the excitement that was so present throughout most of my career.

It took me a long time to accept things, and for the next two years, I basically forced myself to try and get through the ‘creative burnout’ that I thought I was experiencing.

Looking back now, I’ve realised that I was having a hard time removing the label that I’d put on myself. A landscape photographer is what I knew myself as, and I figured that’s what people expected me to be. I was essentially stuck inside a box that I’d created and I was hesitant to make or share any other type of work.

I ended up getting to a point where I decided I had two options: Quit photography entirely (which I considered on multiple occasions), or, move on from my old work, follow my curiosity, and focus on whatever truly excited me regardless of how I thought it may be received.

The Schist Village

The star of this story is a rock – schist – a hard, sometimes beautiful, rock that has greatly influenced the lives of the people who live on it and who exploit it to create fascinating buildings.

It has always been my belief that the landscape is not just something beautiful and fascinating to look at; it is also a major shaper of human activity at multiple levels, and is in its turn moulded by the decisions and actions of people. In fact, the landscape we see today in much of the world, certainly in most of Europe, is the outcome of the interwoven stories of nature and the human exploitation of the environment. In this sense, our appreciation of a landscape is enhanced by some awareness of how it got to look this way. Landscape photography and environmental awareness are natural companions.

This article and the accompanying portfolio try to examine some of these connections for just one place – a small village, a hamlet we’d call it in Britain, in Central Portugal called Cerdeira that was completely abandoned before restoration efforts began about 30 years ago.

The images

The photographs here can be thought of as my tribute to the schist. The character of the rock defines the region and I made three brief visits (2 to 5 days each) in 2018 – January, May and December. I had chance to see the buildings and ruins of Cerdeira in many moods, from the almost absurdly golden light just before a winter sunset to a summer thunderstorm. What kept attracting me was the rock itself. There is an irregular, almost mosaic, character to the walls of the buildings. The highly diverse beauty of the stonework contrasts with the more regular geometry of the tile roofs, though even up there, slabs of schist are left on top of the tiles, as the traditional methods of roofing are flimsy and the blocks provide extra stability.

I would describe the resulting images as highly detailed semi-abstracts. Like millions before me, I feel that the essence of each photograph goes back to Ansel Adams’s concept of “visualisation”. As he put it, this involves seeing a photograph “in your mind’s eye”, knowing the finished image you wish to create, and then taking the steps needed to make the photograph that corresponds to this internal image. In an interview late in his life, he was very clear: “The picture has to be there, clearly and decisively.”

In practical terms, I also follow Guy Tal’s advice, as expressed in his book The Landscape Photographer’s Guide to Photoshop, i.e. I do not try to create the image that corresponds to my visualisation in the field, but rather I take a photograph that will enable me to reproduce that inner vision once I work on it on my laptop. I use Photoshop, but in fact, I find that my visualisations can be found using just a few of its features. Most of the editing goes no further than the tools available in Camera Raw, along with selected dodging and burning. Of course, processing was also a feature of Adams’s methods, so the approach goes back almost a century, even if today we use software when Adams relied on chemicals and length of exposure. The key element for me in the field is the composition; that is the essence of my visualisation. I should also note that these photographs, like all I make, are handheld. I have never been able to work comfortably with a tripod. In the past, this meant accepting that much of landscape photography was beyond my grasp. However, with modern sensors and stabilized lenses, the extra stability of a tripod is no longer needed for a much wider range of images.

The idea that an artist is someone who looks at the same world but sees it differently is a cliché of such long-standing that I have never been able to identify an initial author, and there is at least tentative evidence from cognitive science to support the contention.

The rock and its impact

In traditional, pre-industrial societies locally available resources are critical; the nature of the bedrock determines what building material is available. Schist is hard, created when softer sedimentary rocks were squeezed and baked, deep in the earth hundreds of millions of years ago when continents collided. Hard and impermeable, schist splits easily along the grain of the rock, but it cannot readily be cut into regular blocks. So, buildings traditionally were assembled from irregular-shaped pieces. With the ingredients needed for mortar hard to come by locally, the walls were largely made of solid uncemented stone, pieced together like a three-dimensional jigsaw or mosaic and mortar limited to filling in holes. Schist also varies greatly in colour, both from quarry to quarry and over time as it weathers. Freshly cut, it is often blue or purple, but can also be yellow or orange, and it weathers to a great variety of shades and textures. In the humid climate of Portugal, the stone also acquires a patina of lichens, further enriching the palette of colours. The result, to my eyes, is one of the most diverse and beautiful building materials to be found anywhere, and the specialist builders who now reconstruct the old houses have an eye for this beauty that leads me to think of them as artists rather than artisans. But the rock has an impact that goes far beyond house-building.

Obdurate schist resists erosion and makes hills and mountains with poor soil and steep slopes. In Portugal people have lived in these regions for thousands of years – they were already long-established when the Romans arrived over 2,000 years ago. But these hills have always been tough, marginal places to live in compared with the more fertile lowlands. When opportunity arose to move to towns and cities, or even abroad, people did so, especially after World War Two. Gradually the schist hills began to empty and by the 1970s Cerdeira was a ghost village, its houses abandoned and crumbling, its farm terraces, created with so much effort on the rugged slopes, returning to nature. Rural depopulation of this kind is a widespread phenomenon; across whole swathes of Southern and Eastern Europe farms, villages, even small towns are emptying.

Visiting these abandoned villages, or ones where a handful of residents still linger, is a poignant experience. These are places where people have struggled to make a living for hundreds, even thousands, of years, often in unforgiving conditions. Now they are neglected and decaying. Centuries of effort left to fall into ruins - especially saddening in places where the traditional buildings are often so beautiful. Walking through Cerdeira on the single, carefully graded, schist footpath that connects the rebuilt houses reveals scene after scene that speaks of decay. A doorway that once was the way into someone’s home, now just leads to a tangle of brambles and weeds. A wall, with a niche in the stonework that once might have held an oil lamp or a candle, is falling apart on an almost daily basis. A door ajar, facing one of the reconstructed houses, only opens to reveal heaps of rubble and a roofless, collapsing interior. In many deserted villages it feels impossible to imagine anything other than gradual decay and disappearance. But the schist has one final, and optimistic, role to play.

After so long making life difficult, in the era of ecotourism and sustainable development, the rock has given the communities that live on it a new identity – the Schist Villages. Some two dozen communities have come together to work collectively to establish themselves as a destination for “green tourism” with an emphasis on traditional design, access to nature, and high-quality local produce. In Cerdeira, after decades totally abandoned, it is not fanciful to speak of resurrection. Guided by the creative instincts of ceramicist Kerstin Thomas, the village has become a lively focus for the arts as well as a tourist centre. The photographs here try to give some hint of this transformation.

Photographing Rocks

This article was written in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. I wish to make it clear that at the time of writing the places I was photographing were open to local residents under certain "distancing" conditions. We are now under stricter closure orders, regrettably due to too many non-locals ignoring pleas from local communities to stay away (we have very limited medical and emergency services), and I have shifted my efforts to indoor activities for the time being.

Both you and I are incapable of devoting ourselves to contemporary social significances in our work; […] I still believe there is a real social significance in a rock—a more important significance therein than in a line of unemployed. For that opinion I am charged with inhumanity, unawareness—I am dead, through, finished, a social liability, one who will be “liquidated” when the “great day” comes. Let it come.” ~Ansel Adams (in a letter to Edward Weston, 1934)

During the turbulent days of the early 1930s, around the time of the founding of Group f/64 (by, among others, Ansel Adams and Edward Weston), Henri Cartier-Bresson is rumoured to have commented, “The world is going to pieces and people like Adams and Weston are photographing rocks!”

To me, Cartier-Bresson’s comment exemplifies an unfortunate philosophical prejudice that pervades many of our arts, sciences, and other pursuits—the prejudice of humanism—suggesting implicitly that the welfare of the human species and qualities of the so-called “human condition” must always be considered of supreme importance over any other subject. It’s a notion that has never resonated with me, as a person and as an artist. The natural world has enriched my own life more profoundly and in more ways than any human-centric enterprise. Much as I respect the life and work of Cartier-Bresson and so many others whose world views are different than my own; and much as I enjoy the visual poignancy of “decisive moments,” and the skill and genius required to photograph them; photographs of rocks, and the legacies of photographers such as Weston and Adams, have been considerably more important and consequential to me.

Although I respect those who feel otherwise, so much photography amounting to humanity gazing into its own navel, fascinated by its own oddities, superstitions, rituals, shortfalls, and miseries; has never interested me as much as the vast world beyond the vanities and tragedies of our species, and generally less so than all the stories, lessons, and metaphors to be found in rocks, and in photographing rocks. As E.O. Wilson points out, “The main shortcoming of humanistic scholarship is its extreme anthropocentrism. Nothing, it seems matters in the creative arts and critical humanistic analyses except as it can be expressed as a perspective of present-day literate cultures. Everything tends to be weighed by its immediate impact on people. Meaning is drawn from that which is valued exclusively in human terms. The most important consequence is that we are left with very little to compare with the rest of life. The deficit shrinks the ground on which we can understand and judge ourselves.”

Issue 204 PDF

End frame: ‘Salt’ by Murray Fredericks

I can't remember the exact moment in time when I became aware of Murray Fredericks work, but I have very distinct sensory memory recognition of the first pass through his ‘Salt’ gallery. A red desert, a green tent, dark skies, pastel skies, mirror reflections, stars, abstracted but equally tangible and definable. Balanced simplicity, with incredible colour combinations, nothing and everything all at once. Putting my finger on one single image is impossible. They worked as a collective, and for me, this was much more powerful than any single image could ever be.